11 May 2015 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Middle East and North Africa, mobile, News, Statements

Bahraini human rights defender Nabeel Rajab (Photo: The Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy)

Index on Censorship has condemned the latest extension to the detention of Bahraini human rights activist Nabeel Rajab on spurious charges. He was arrested in early April over comments made on Twitter regarding abuses at Bahrain’s Jaw prison and the crisis in Yemen. On 11 May, Bahraini authorities, who had already extended Rajab’s pre-trial detention several times, prolonged his detention for a further two weeks.

“Bahrain has committed publicly to respecting human rights, but continues to flout its international commitments by denying its citizens the right to peaceful protest, peaceful assembly, and to free expression,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg. “We urge the new UK government to use its position as an ally of Bahrain to ensure the country upholds those commitments and ends the harassment of Nabeel Rajab and his fellow democracy activists.”

Earlier this year, Bahrain revoked the citizenship of 72 individuals, including journalists, bloggers, and political and human rights activists, rendering many of them stateless — as part of its latest attempt to crack down on those critical of the government.

Rajab was handed down a six-month suspended sentence pending payment of a fine in January for a tweet that both the ministry of interior and the ministry of defence claimed “denigrated government institutions”.

The tweet in question stated:

Since then, Rajab’s appeal against the verdict has been postponed repeatedly and he was arrested on 2 April over subsequent tweets and an opinion piece published on the Huffington Post. If he is convicted on all current charges, Rajab could face more than 10 years in prison.

Rajab is a former winner of a Index on Censorship freedom of expression award, president of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights and a member of Human Rights Watch’s Middle East Advisory Board. He has continuously been targeted by Bahraini authorities over his human rights campaigning work. He was released in May 2014 after spending two years in prison on spurious charges including writing offensive tweets and taking part in illegal protests.

Last month, Rajab’s civil society colleagues human rights defender Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja and political activist Salah Al-Khawaja were prevented from attending the funeral of their eldest brother Abdulaziz, who passed away in Bahrain. Abdulhadi is serving a life sentence due to his human rights work and Salah is serving five years for his political activism; both are prisoners of conscience and torture survivors.

This article was posted on 11 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

7 May 2015 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News

From top left: Arif Yunus, Rasul Jafarov, Leyla Yunus, Khadija Ismayilova, Intigam Aliyev and Anar Mammadli – some of the government critics jailed on trumped up charges in Azerbaijan

For the first time since the 2012 Eurovision Song Contest, the oil-rich, rights-poor nation of Azerbaijan is drawing widespread international attention. This June, the country is poised to host the inaugural European Games, which will bring an estimated 6,000 athletes from 50 countries to the capital city of Baku to compete in 20 sports.

Ahead of the games, the Azerbaijani regime has spent a great deal of time and money to promote a positive image abroad. At home, however, it is engaged in a brutal human rights crackdown. This has particularly intensified over the past year, as the authorities have worked aggressively to silence all forms of criticism and dissent.

Dozens of democracy activists are now in prison, including celebrated investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova who was given this year’s PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award, and Leyla Yunus, one of the country’s most prominent human rights defenders. They, and many others, have been jailed on spurious charges, with some facing prison sentences of up to 12 years. Meanwhile, press freedom campaigner Emin Huseynov is trapped in the Swiss embassy in Baku, facing arrest if he leaves. These individuals have been targeted for their work defending the rights of others and telling the truth about the situation in their country.

So far, the European Olympic Committees has been happy to look the other way, stating that was “not the EOC’s place to challenge or pass judgment on the legal or political processes of a sovereign nation”. Likewise, the event sponsors do not seem bothered: BP stated that “seeking to influence the policies of sovereign governments” was not part of its role. The Sport for Rights campaign hopes, however, that the next prime minister will think twice.

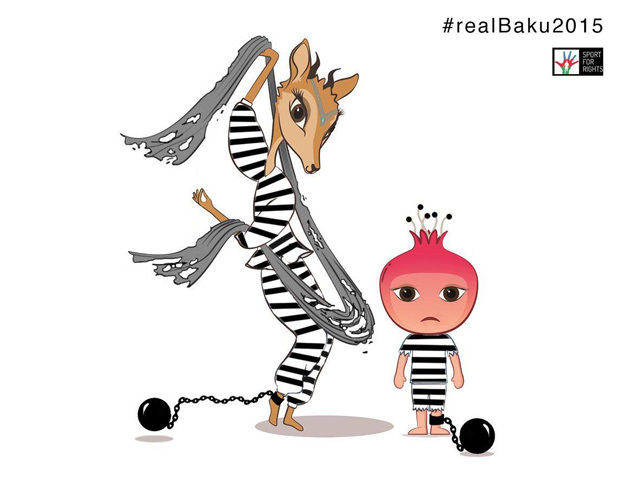

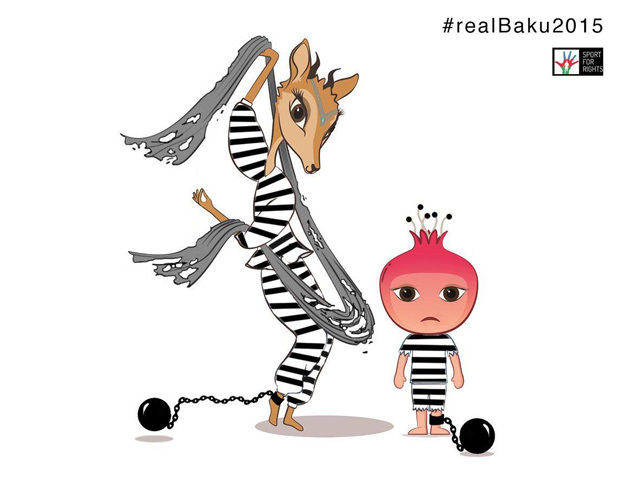

The Sport for Rights campaign’s take on Baku European Games mascots Jeyran and Nar. (Image: Sport for Rights)

As members of the campaign, Article 19, Index on Censorship, and Platform have written to the leaders of the UK’s Labour, Conservative, Liberal Democrat, and Green parties on the eve of the general election. The campaign urged them to make statements condemning the on-going attacks on human rights and calling for the release of political prisoners in Azerbaijan.

Sport for Rights also called on the party leaders to make their participation in the opening ceremony of the games contingent upon the release of the country’s jailed journalists and human rights defenders. This is not a call for a boycott of the games by athletes or the public, but a request for the next prime minister not to miss a key opportunity to take an important stand.

In the face of growing repression in Azerbaijan, the response from the British government has so far been weak and sporadic. Statements are occasionally made; the most recent expressed that the UK was “dismayed” by the sentencing of human rights lawyer Intigam Aliyev, but stopped short of calling for his release, as did the previous statement conveying that the UK was “deeply troubled” by the sentencing of human rights defender Rasul Jafarov. But beyond statements, little else has been done — at least in the public eye.

For a country so intent on promoting its image as a modern, glamorous, international player, key political figures taking a public stand on human rights issues would have a real chance of impacting positive, democratic change. The European Games presents a timely opportunity for the next prime minister to do just that, sending the clear signal that human rights are important in the bilateral relationship.

Conversely, attendance by the prime minister at the opening ceremony of the games in the current climate, without securing the release of the jailed journalists and human rights defenders, would only serve to effectively endorse an increasingly authoritarian regime. In helping to whitewash Azerbaijan’s ever-worsening image, the UK would only end up tarnishing its own.

This article was posted on 6 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

7 May 2015 | Denmark, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News

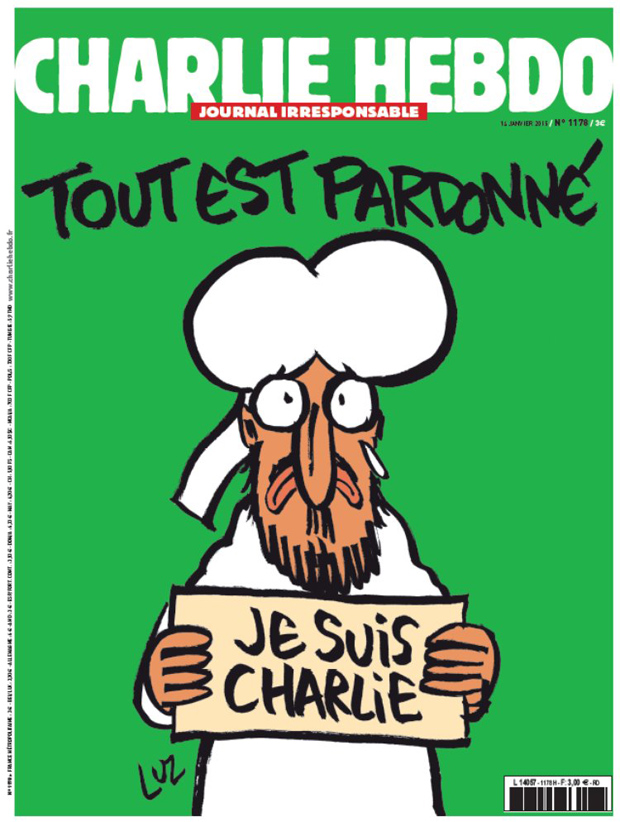

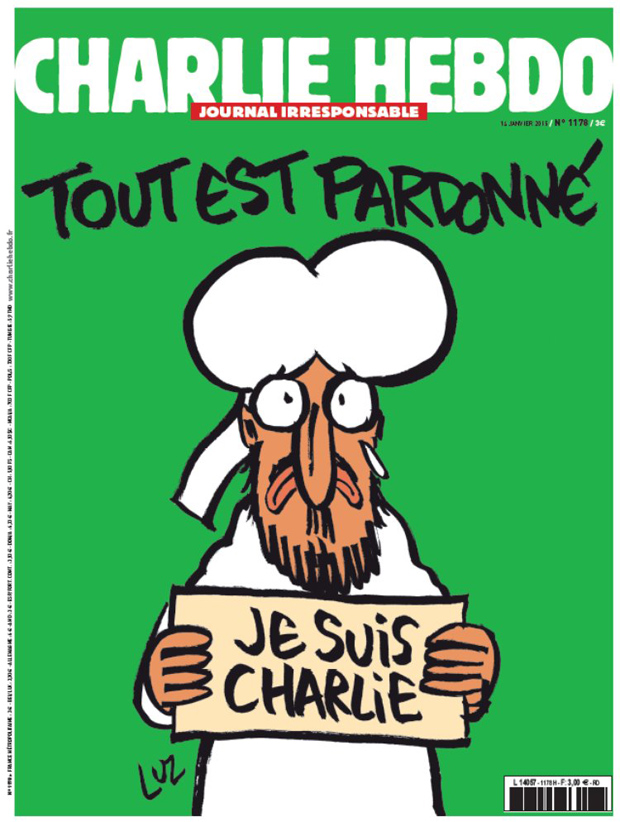

Tout est pardonne or All is forgiven, the first post attack cover of Charlie Hebdo

It’s now almost ten years since Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published a set of cartoons, some of which (though by no means all) depicted the Islamic prophet Mohammed. Some were flattering, some were not. One mocked jihadist suicide bombers. Another showed a schoolboy called Mohammed calling Jyllands-Posten’s editors bigots.

The idea came after it was reported that a Swedish children’s author could not find someone to illustrate her book on the life of Mohammed. Flemming Rose of Jyllands-Posten decided to commission cartoonists to draw the apparently taboo figure.

As an exercise in taboo-busting, it was bound to be controversial. But controversial though some were (one showed the prophet as a scimitar wielding menace, another a figure with a bomb for a turban) they were not shocking enough for the Danish-based radicals who decided to make a campaign of the issue. In an astonishing act of chutzpah (there really is no other word), Ahmad Abu Laban decided to fill out a “dossier” on the cartoons with even more offensive characterisations, some of which had nothing to do with Mohammed at all. He and his colleague Ahmed Akkari took the dossier to the Middle East, apparently to prove the level of anti-Muslim hatred in Denmark. Chaos ensued. The rest, the usual line would go, is history. But that wouldn’t be true: the “rest” is very much the present, and perhaps pressing now more than at any time in the past 10 years.

One wonders if Ahmad Abu Laban quite knew what he was getting us all in to. Certainly, the man, who died in 2007, was of what is now a familiar figure in western Europe. The self-publicising Muslim spokesman: the go-to guy for a controversial quote for a press not quite sure of the heat of the flames with which they were playing. Omar Bakri Muhammad, for example, was first introduced to the British public as a ridiculous fantasist in Jon Ronson’s documentary The Tottenham Ayatollah. His proteges in al-Muhajiroun provided a steady flow of enjoyably ridiculous bogeymen such as Anjem Choudary and Abu Izzadeen, who in 2006 was given the main interview on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme. Subsequent news bulletins carried his warnings of “Muslim anger” as if he were some sort of pope, rather than a fringe figure with highly dubious links.

Everyone enjoyed these outrageous figures for a while, until we realised the damage they could do. Practically every home-grown jihadist in Britain has had dealings with al-Muhajiroun. The late Laban may have known of the chaos he was about to unleash on the Middle East in 2006 with his dossier, and indeed the world ever since. He may not. His former comrade Akkari repented in 2013, saying: “I want to be clear today about the trip: It was totally wrong. At that time, I was so fascinated with this logical force in the Islamic mindset that I could not see the greater picture. I was convinced it was a fight for my faith, Islam.”

Well good, but a little late now.

Since 2005 we have been embroiled in an absurd abysmal dream. Some people draw cartoons of a long-dead religious figure. Some other people decide this has offended some sacred, though undefined, law, and so they decide that the people who drew the cartoons must be killed. Repeat. What chronic stupidity.

But of course there’s more going on here. There is more than one reason to draw or publish Mohammed drawings: from plainly making a free speech point (as many publications did after the Charlie Hebdo murders), to anti-clericalism (a la Charlie itself), to deliberate antagonism towards Muslims (a la Pamela Geller). Not all Motoons are the same.

Nor are all responses on the same spectrum. There is a world of difference between the average Muslim who may be annoyed by a portrayal of Mohammed and a jihadist who takes it upon himself to find people who have drawn these portrayals and kill them or attempt to kill them.

This is the error that has plagued the debate for the past 10 years, and came to light again in the past few weeks with PEN’s awarding of a prize to Charlie Hebdo, and the attack on a Pamela Geller-organised rally in Texas which featured a “draw Mohammed” competition.

There has been an unwitting acceptance of several dangerous ideas, chief amongst them that in order to have respect for someone as a human being, one must respect all their beliefs, and observe their taboos. But as novelist and long-time PEN activist Hari Kunzru put it: “It is not solidarity with the oppressed to offer ‘respect’ to an idea just because it’s held by some oppressed people.”

Following from this is the idea that all expression that disrespects beliefs and taboos must be driven by bigotry and racism, and that to stand against bigotry and racism is to stand against any such expression. There is a sad irony in this failure to discriminate.

On the reverse of this, some Muslims feel that free speech is now something that is being used to batter them over the head, rather than protect them. This in itself is a failure of civil society: the moment we decide everyone with a certain background and set of beliefs can be put in the “Muslim” box is the moment we ensure that those who shout loudest about those beliefs — the “extremists” — are given status. Ahmad Abu Laban, for example, claimed that his Islamic Society of Denmark represented all Danish Muslims.

So now what? As we’re approaching 10 long years of this argument, is there hope for resolution any time soon? I fear not. There can be no accommodation between those who believe in the right to free expression and those who believe “blasphemy” should carry the death sentence.

In between, if it does prove impossible not to take sides, we can at least make sure our arguments are clear and our ears are listening.

This article was posted on 7 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

1 May 2015 | Campaigns, mobile, Statements

On World Press Freedom Day, 116 days after the attack at the office of the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo that left 11 dead and 12 wounded, we, the undersigned, reaffirm our commitment to defending the right to freedom of expression, even when that right is being used to express views that we and others may find difficult, or even offensive.

The Charlie Hebdo attack – a horrific reminder of the violence many journalists around the world face daily in the course of their work – provoked a series of worrying reactions across the globe.

In January, the office of the German daily Hamburger Morgenpost was firebombed following the paper’s publishing of several Charlie Hebdo images. In Turkey, journalists reported receiving death threats following their re-publishing of images taken from Charlie Hebdo. In February, a gunman apparently inspired by the attack in Paris, opened fire at a free expression event in Copenhagen; his target was a controversial Swedish cartoonist who had depicted the prophet Muhammad in his drawings.

A Turkish court blocked web pages that had carried images of Charlie Hebdo’s front cover; Russia’s communications watchdog warned six media outlets that publishing religious-themed cartoons “could be viewed as a violation of the laws on mass media and extremism”; Egypt’s president Abdel Fatah al-Sisi empowered the prime minister to ban any foreign publication deemed offensive to religion; the editor of the Kenyan newspaper The Star was summoned by the government’s media council, asked to explain his “unprofessional conduct” in publishing images of Charlie Hebdo, and his newspaper had to issue a public apology; Senegal banned Charlie Hebdo and other publications that re-printed its images; in India, Mumbai police used laws covering threats to public order and offensive content to block access to websites carrying Charlie Hebdo images. This list is far from exhaustive.

Perhaps the most long-reaching threats to freedom of expression have come from governments ostensibly motivated by security concerns. Following the attack on Charlie Hebdo, 11 interior ministers from European Union countries, including France, Britain and Germany, issued a statement in which they called on internet service providers to identify and remove online content “that aims to incite hatred and terror”. In the UK, despite the already gross intrusion of the British intelligence services into private data, Prime Minister David Cameron suggested that the country should go a step further and ban internet services that did not give the government the ability to monitor all encrypted chats and calls.

This kind of governmental response is chilling because a particularly insidious threat to our right to free expression is self-censorship. In order to fully exercise the right to freedom of expression, individuals must be able to communicate without fear of intrusion by the state. Under international law, the right to freedom of expression also protects speech that some may find shocking, offensive or disturbing. Importantly, the right to freedom of expression means that those who feel offended also have the right to challenge others through free debate and open discussion, or through peaceful protest.

On World Press Freedom Day, we, the undersigned, call on all governments to:

• Uphold their international obligations to protect the rights of freedom of expression and information for all, especially journalists, writers, artists and human rights defenders to publish, write and speak freely;

• Promote a safe and enabling environment for those who exercise their right to freedom of expression, especially for journalists, artists and human rights defenders to perform their work without interference;

• Combat impunity for threats and violations aimed at journalists and others threatened for exercising their right to freedom of expression and ensure impartial, speedy, thorough, independent and effective investigations that bring masterminds behind attacks on journalists to justice, and ensure victims and their families have speedy access to appropriate remedies;

• Repeal legislation which restricts the right to legitimate freedom of expression, especially such as vague and overbroad national security, sedition, blasphemy and criminal defamation laws and other legislation used to imprison, harass and silence journalists and others exercising free expression;

• Promote voluntary self-regulation mechanisms, completely independent of governments, for print media;

• Ensure that the respect of human rights is at the heart of communication surveillance policy. Laws and legal standards governing communication surveillance must therefore be updated, strengthened and brought under legislative and judicial control. Any interference can only be justified if it is clearly defined by law, pursues a legitimate aim and is strictly necessary to the aim pursued.

PEN International

Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

Africa Freedom of Information Centre

Albanian Media Institute

Article19

Association of European Journalists

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Belarusian PEN

Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism

Cambodian Center for Human Rights

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

Centre for Independent Journalism – Malaysia

Danish PEN

Derechos Digitales

Egyptian Organization for Human Rights

English PEN

Ethical Journalism Initiative

Finnish PEN

Foro de Periodismo Argentino

Fundamedios – Andean Foundation for Media Observation and Study

Globe International Center

Guardian News Media Limited

Icelandic PEN

Index on Censorship

Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information

International Federation of Journalists

International Press Institute

International Publishers Association

Malawi PEN

Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance

Media Institute of Southern Africa

Media Rights Agenda

Media Watch

Mexico PEN

Norwegian PEN

Observatorio Latinoamericano para la Libertad de Expresión – OLA

Pacific Islands News Association

PEN Afrikaans

PEN American Center

PEN Catalan

PEN Lithuania

PEN Quebec

Russian PEN

San Miguel Allende PEN

PEN South Africa

Southeast Asian Press Alliance

Swedish PEN

Turkish PEN

Wales PEN Cymru

West African Journalists Association

World Press Freedom Committee

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression