19 Jul 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Greece, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

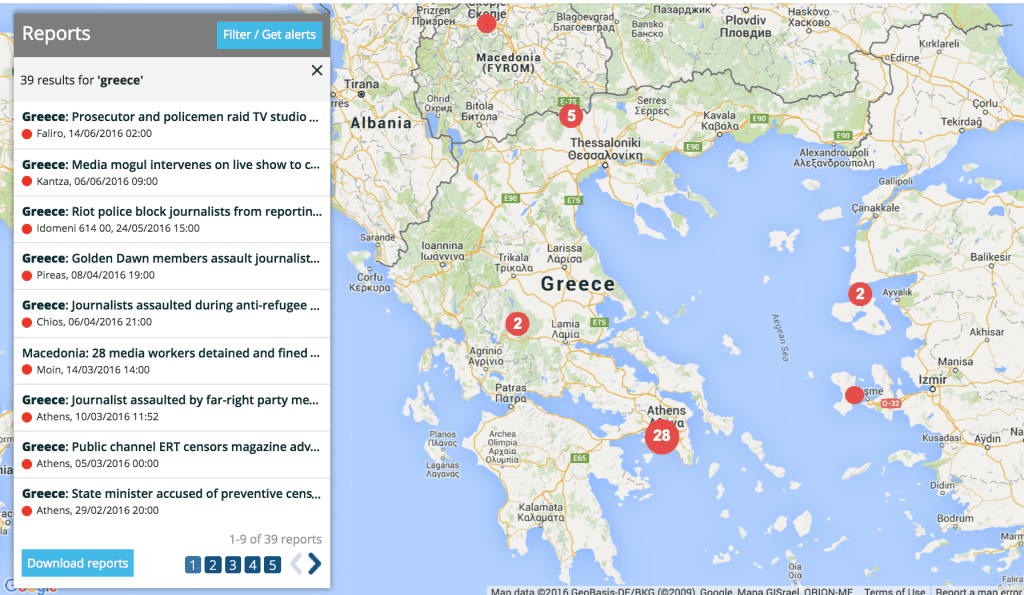

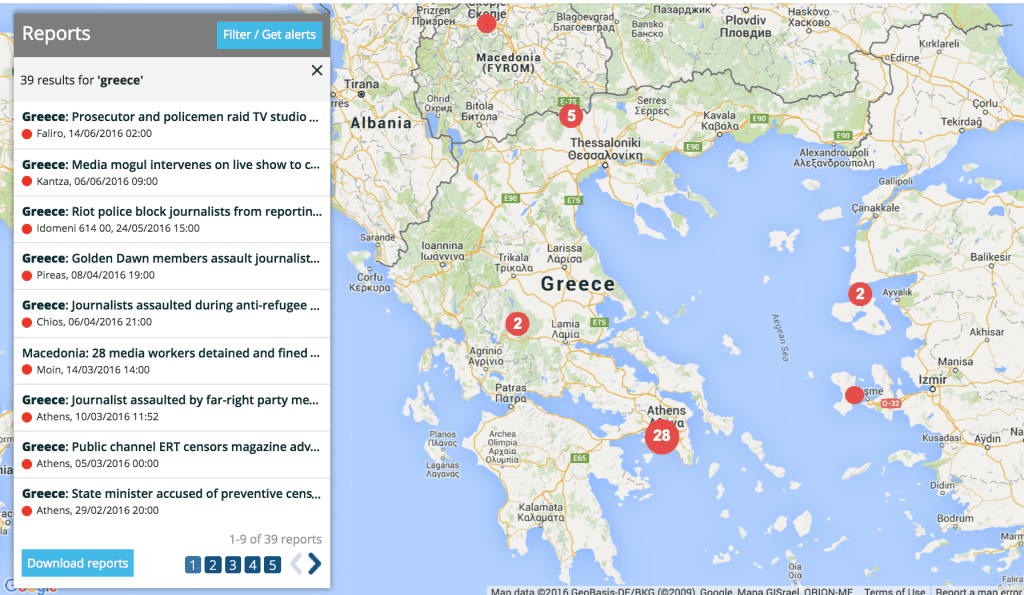

As Greece tries to deal with around 50,000 stranded refugees on its soil after Austria and the western Balkan countries closed their borders, attention has turned to the living conditions inside the refugee camps. Throughout the crisis, the Greek and international press has faced major difficulties in covering the crisis.

“It’s clear that the government does not want the press to be present when a policeman assaults migrants,” Marios Lolos, press photographer and head of the Union of Press Photographers of Greece said in an interview with Index on Censorship. “When the police are forced to suppress a revolt of the migrants, they don’t want us to be there and take pictures.”

Last summer, Greece had just emerged from a long and painful period of negotiations with its international creditors only to end up with a third bailout programme against the backdrop of closed banks and steep indebtedness. At the same time, hundreds of refugees were arriving every day to the Greek islands such as Chios, Kos and Lesvos. It was around this time that the EU’s executive body, the European Commission, started putting pressure on Greece to build appropriate refugee centres and prevent this massive influx from heading to the more prosperous northern countries.

It took some months, several EU Summits, threats to kick Greece out of the EU free movement zone, the abrupt closure of the internal borders and a controversial agreement between the EU and Turkey to finally stem migrant influx to Greek islands. The Greek authorities are now struggling to act on their commitments to their EU partners and at the same time protect themselves from negative coverage.

Although there were some incidents of press limitations during the first phase of the crisis in the islands, Lolos says that the most egregious curbs on the press occurred while the Greek authorities were evacuating the military area of Idomeni, on the border with Macedonia.

In May 2016, the Greek police launched a major operation to evict more than 8,000 refugees and migrants bottlenecked at a makeshift Idomeni camp since the closure of the borders. The police blocked the press from covering the operation.

“Only the photographer of the state-owned press agency ANA and the TV crew of the public TV channel ERT were allowed to be there,” Lolos said, while the Union’s official statement denounced “the flagrant violation of the freedom and pluralism of press in the name of the safety of photojournalists”.

“The authorities said that they blocked us for our safety but it is clear that this was just an excuse,” Lolos explained.

In early December 2015, during another police operation to remove migrants protesting against the closed borders from railway tracks, two photographers and two reporters were detained and prevented from doing their jobs, even after showing their press IDs, Lolos said.

While the refugees were warmly received by the majority of the Greek people, some anti-refugee sentiment was evident, giving Greece’s neo-nazi, far-right Golden Dawn party an opportunity to mobilise, including against journalists and photographers covering pro- and anti-refugee demonstrations.

On the 8 April 2016, Vice photographer Alexia Tsagari and a TV crew from the Greek channel E TV were attacked by members of Golden Dawn while covering an anti-refugee demonstration in Piraeus. According to press reports, after the anti-refugee group was encouraged by Golden Dawn MP Ilias Kasidiaris to attack anti-fascists, a man dressed in black, who had separated from Golden Dawn’s ranks, slapped and kicked Tsagari in the face.

“Since then I have this fear that I cannot do my work freely,” Tsagari told Index on Censorship, adding that this feeling of insecurity becomes even more intense, considering that the Greek riot police were nearby when the attack happened but did not intervene.

Following the EU-Turkey agreement in late March which stemmed the migrant flows, the Greek government agreed to send migrants, including asylum seekers, back to Turkey, recognising it as “safe third country”. As a result, despite the government’s initial disapproval, most of the first reception facilities have turned into overcrowded closed refugee centres.

“Now we need to focus on the living conditions of asylum seekers and migrants inside the state-owned facilities. However, the access is limited for the press. There is a general restriction of access unless you have a written permission from the ministry,” Lolos said, adding that the daily living conditions in some centres are disgraceful.

Ola Aljari is a journalist and refugee from Syria who fled to Germany and now works for Mapping Media Freedom partners the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom. She visited Greece twice to cover refugee stories and confirms that restrictions on journalists are increasing.

“With all the restrictions I feel like the authorities have something to hide,” Aljari told Index on Censorship, also mentioning that some Greek journalists have used bribes in order to get authorisation.

Greek journalist, Nikolas Leontopoulos, working along with a mission of foreign journalists from a major international media outlet to the closed centre of VIAL in Chios experienced recently this “reluctance” from Greek authorities to let the press in.

“Although the ministry for migration had sent an email to the VIAL director granting permission to visit and report inside VIAL, the director at first denied the existence of the email and later on did everything in his power to put obstacles and cancel our access to the hotspot,” Leontopoulos told Index on Censorship, commenting that his behaviour is “indicative” of the authorities’ way of dealing with the press.

18 Jul 2016 | Africa, Magazine, mobile, South Africa

Index has released a special collection of apartheid-era articles from the Index on Censorship magazine archives to celebrate Nelson Mandela day 2016. Holly Raiborn has selected the collection, tracing the breadth of writing during the apartheid era from authors both in the country and in exile. The articles selected trace the history of this period in South Africa’s history. Significant South African writers, including Nadine Gordimer, Don Mattera, Pieter-Dirk Uys and Desmond Tutu, discuss the impacts this era of oppression had on themselves, their peers and their country. The collection will now form a reading list available to students who are researching the apartheid years, and will be available via Sage Publishing in university libraries.

Before 1948 “apartheid” was just a word in Afrikaans with a simple meaning: separateness. However, over the course of the next 50 years, the word “apartheid” would take on a new level of significance. The connotation of the word grew darker with every dissident banned, prisoner tortured, child left uneducated and home destroyed. Apartheid is no longer just a word; it carries the history of brutality, censorship and maltreatment of South Africans. For a limited period, Index and Sage are making the collection free to non-subscribers. For those who want to study the history of censorship further, Index on Censorship magazine’s archives are held at the Bishopsgate Institute in London and are free to visit.

Nadine Gordimer, Apartheid and “The Primary Homeland”

1972; vol. 1, 3-4: pp. 25-29

An address regarding the 1972 plans of the South African government to abolish the right of appeal against decisions brought by the State Publications Control Board, effectively ridding writers of a means to combat the rulings of government-appointed censors. The censorship in South Africa at this time caused a breakdown in communication between “the sections of a people carved up into categories of colour and language.”

Frene Ginwala, The press in South Africa

1973; vol. 2, 3: pp. 27-43

An extensive report on the state of the “free” press in South Africa prepared for the United Nations’ Unit on Apartheid in November 1972. Ginwala posits that apartheid attempts to segregate freedom and this attempt “extinguishes freedom itself”.

Robert Royston, A tiny, unheard voice: The writer in South Africa

1973; vol. 2, 4: pp. 85-88

A personal narrative reflecting the experiences of Robert Royston as a black poet in South Africa during a period of popularity for black poetry amongst white readers. Royston describes a disconnect between the language he speaks and the language understood by the government and white citizens, although they technically share the same tongue.

Jack Slater, South African Boycott: Helping to enforce apartheid?

1975; vol. 4, 4: pp. 32-34

An article by a New York Sunday Times staff writer arguing that the proposed cultural boycott would ultimately negatively affect black South Africans more than white South Africans who were merely irritated. Slater feared black South Africans suffer from feelings of isolation from the outside world because of the cultural boycott.

Benjamin Pogrund, The South African press

1976; vol. 5, 3: pp. 10-16

A discussion regarding the often contradictory aspects of the South African “free” press in which newspapers censor themselves. Strict laws preventing communism, sabotage and terrorism were often twisted to prevent the publications of black viewpoints.

John Laurence, Censorship by skin colour

1977; vol. 6, 2: pp. 40-43

In the UK in the 1970s, news about South Africa was contributed by the white minority while black South Africans were not interviewed by major European news outlets about events predominantly affecting their community such as the Soweto riots. This article discusses the clear racial bias, blaming it for the misinformation and misconceptions in Europe about apartheid-era South Africa.

Brief reports: Bad days in Bedlam

1978; vol. 7, 1: pp. 52-54

A report regarding the glaring health violations within the overwhelmingly black South African mental hospitals that were largely ignored due to racial factors and censorship brought about with the 1959 Prisons Act. This act made reporting “false information” on prisons or prisoners punishable with jail time or fines which led to prison and mental patient camp, conditions being largely neglected in the media.

Robert Birley, End of the road for “Bandwagon”

1978; vol. 7, 2: pp. 6-8

An article about a significant yet short-lived South African journal, Bandwagon, whose purpose was to unite individuals banned under the Suppression of Communism Act. The act featured strictly enforced limits on social life and essentially made any meetings, social or otherwise, illegal for a banned person; therefore, the impact and importance of this publication should not be understated.

William A. Hachten, Black journalists under apartheid

1979; vol. 8, 3: pp. 43-48

Hachten discusses the new found power of being a black journalist (the literacy rate of black South Africans had recently surpassed whites) and the growing hazards of the profession in the late 1970s. Journalists were arrested for reporting the events of the Soweto riots and faced constant police and legislative pressure on top of fines and censorship imposed by the white-controlled newspapers they had no choice but to work for.

Don Mattera, Open Letter to South African whites

1980; vol. 9, 1: pp. 49-50

An address from a banned poet who pointed out the cruelty of white South African society so that they may never claim ignorance to the atrocities. He questions why his words are deemed so dangerous that he is not allowed to attend social gatherings like birthdays and funerals

Nadine Gordimer, The South African censor: No change

1981; vol. 10, 1: pp 4-9

Gordimer hypothesised that the successful appeal of her novel’s banning, and that of many novels by other white writers, was due to the fact that she is white. She argued that South Africa would never be rid of censorship until it was rid of apartheid.

Donald Woods, South Africa: Black editors out

1981; vol. 10, 3: pp. 32-34

Woods wrote about the shift from editors of South African newspapers facing fines for disobeying censorship statutes to jail time in the late 1970s and explained that this shift signalled that dissent and bold writing was permitted in white politics but would not be permitted from black perspectives. He argued that the reason the government did not censor the press entirely was because they enjoyed the façade of a “free press” and there was no reason for them to need full censorship.

Keyan Tomaselli, Siege mentality: A view of film censorship

1981; vol. 10, 4: pp. 35-37

Tomaseli explained that censorship was often as financially driven as it is culturally. He wrote that censorship interferes at three stages, namely during: finance, distribution and through state censorship law. Tomaseli expands on the circumstances that led to many different films being banned or harshly edited.

Mbulelo Vizikhungo Mzamane, No place for the African: South Africa’s education system, meant to bolster apartheid, may destroy it

1981; vol. 10, 5: pp. 7-9

Mzamane claimed that the Bantu Education Act of 1956 was clearly a ploy to create compliant Africans within a society increasingly controlled by Afrikaners. Bantu schools were essentially vocational training for servitude to whites and textbooks were blatant indoctrination, he argued.

Christopher Hope, Visible Jailers: A South African writer casts a humorous eye over the bannings by his country’s censors between 1979 and 1981

1982; vol. 11, 4: pp. 8-10

A clever take on the South African censor. Hope addresses the reasons and methodology of the South African censor with tongue and cheek commentary as he reviews the Publications Appeal Board: Digest of Decisions. This collection is comprised of the totality of decisions made by the South African Publications Appeal Board.

Sipho Sepamla, The price of being a writer

1982; vol. 11, 4: pp. 15-16

Sepamla writes about the struggles of continuing to write under such strict scrutiny by censors after the banning of his latest novel, A Ride on the Whirlwind. He speaks of the disenchantment experienced by any writer that has faced censorship and specifically black South African writers who faced this treatment all too often.

Barry Gilder, Finding new ways to bypass censors: How apartheid affects music in South Africa

1983; vol. 12, 1: pp. 18-22

Music was divided along race and class lines. Music was banned under the Publications Act if it was found to be unsafe to the state, harmful to the relationship between members of any sections of society, blasphemous, or obscene Songs with even symbolic mention of freedom or revolution were banned.

Barney Pityana, Black theology and the struggle for liberation

1983; vol. 12, 5: pp. 29-31

Reverend Pityana wrote of the paradox that Christianity teaches that all are equal under god but the church in South Africa still degraded and segregated. He writes that The Bible teaches that all are created in God’s image and the plight of the Jews and other marginalised groups within the Bible give hope, guidance and reassurance to those suffering under apartheid.

Miriam Tlali, Remove the chains: South African censorship and the black writer

1984; vol. 13, 6: pp. 22-26

Tlali, a black female South African novelist, addresses the added difficulties of being black and a woman in Afrikaner-controlled society. She speaks both from personal experience and about the struggles of her peers.

Johannes Rantete, The third day of September

1985; vol. 14, 3: pp. 37-42

An honest first-hand account of the Soweto riots by a 20-year-old unemployed black South African. Rantete wrote a sympathetic eyewitness report of the September riot and the first reaction of the South African authorities to confiscate and ban it.

Alan Paton, The intimidators

1986; vol. 15, 1: pp. 6-7

The white South African novelist on the intimidation tactics and stalking committed by the security police after his controversial novel, Cry, The Beloved Country, was published. He notes that he suspects his treatment would have been even worse had he been black.

Anthony Hazlitt Heard, How I was fired

1987; vol. 16, 10: pp. 9-12

Former editor of the Cape Times, who was awarded the International Federation of Newspaper Publishers’ Golden Pen of Freedom in 1986, Heard was dismissed from his position after his interview with banned leader of the African National Congress Oliver Tambo. Heard speaks about 16 years of editing under apartheid and the circumstances surrounding his dismissal in August 1987.

Anton Harber, Even bigger scissors

1987; vol. 16, 10: pp. 13-14

‘The importance of international pressure in giving a measure of protection to the South African press cannot be overestimated’ wrote the co-editor of the Johannesburg Weekly Mail in this assessment of Botha’s policy towards the alternative press. Harber offered a compelling plea for protection of the South African alternative press by the international media.

Jo-Anne Collinge, Herbert Mabuza, Glenn Moss and David Niddrie, What the papers don’t say

1988; vol. 17, 3: pp. 27-36

An extensive review of restrictions in South Africa at that time including the Defence Act, Police Act, Prisons Act, Internal Security Act and the Publications Act. The writers offer suggestions for the safety and protection of journalists in the future.

Richard Rive, How the racial situation affects my work

1988; vol. 17, 5: pp 97-98, 103

Rive discusses the racial factors that have contributed to his writing style and the works of any black writer in South Africa. He emphasises the hypocrisy of the society he lives in which will criticise black writers as simplistic but not allow quality education and where the books of black writers sitting in libraries that they are not allowed to enter.

Albie Sachs, The gentle revenge at the end of apartheid

1990; vol. 19, 4: pp. 3-8

Albie Sachs was asked by Index on Censorship to look ahead to constitutional reform that was not foreseeable at that point and how to enshrine freedom of expression in a post-apartheid South Africa. Four months later came the unbanning of the ANC on 2 February, the release of Nelson Mandela on 11 February and his reunion with Oliver Tambo in Sweden on 12 March, all of which promised real change. These are extracts from the conversation about a future South Africa. He offers suggestions for the then-looming transition from apartheid to democracy.

Oliver Tambo, We will be in Pretoria soon

1990; vol. 19, 4: pp. 7

In May 1986 Oliver Tambo, president of the African National Congress, was interviewed by Andrew Graham. The ANC president discussed the beginning of the end for apartheid and traces the lineage of the racism that fuelled the apartheid for nearly 50 years. Tambo optimistically plans for a new reign of government made up of representation that actually reflects the populous.

Nadine Gordimer, Censorship and its aftermath

1990; vol. 19, 7: pp. 14-16

On 11 July 1979, Nadine Gordimer’s novel Burger’s Daughter was banned by the South African directorate of publications on the grounds – among others – that the book was a threat to state security. After an international outcry the director of publications appealed against the decision of his own censorship committee to the publications’ appeal board. In this article, Nadine Gordimer reflects on these events, and on the new censorship policy they heralded. Gordimer reflects on censorship under previous administrations and what she expects from President FW de Klerk’s reign as president.

Nadine Gordimer, Act two: one year later

1995; vol. 24, 3: pp. 114-117

A reflection on how far South Africa had come and still had to go by this frequently banned author. Using the Descartes method, Gordimer considers the role reversal that has occurred in post-apartheid South Africa as her once banned colleagues ascend to political power.

Desmond Tutu, Healing a nation

1996; vol. 25, 5: pp. 38-43

An Index interview with Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Tutu discusses the urgency of healing the past before South Africa can truly move on to a brighter future. This brighter future was to be achieved with the aid of the Truth Commission. He argued that only honesty, compassion and forgiveness would lead to national unity in South Africa, even if that means prosecuting former ANC members. He stresses that the commission’s goal is reparations and not compensation.

Pieter-Dirk Uys, The truth, the whole truth, and nothing but…

1996; v0l. 25, 5: pp. 46-47

Famed satirist Pieter-Dirk Uys questioned if information about the atrocities of the apartheid could actually be uncovered by the Truth Commission. Uys asked how the country could heal when so many willing participants in the apartheid already seemed eager to forget or to forge their own accounts of history to avoid blame. His pessimistic view contrasted with that of Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s.

All articles from Index on Censorship magazine, from 1972 to 2016, are available via Sage in most university libraries. More information about subscribing to the magazine in print or digitally here.

14 Jul 2016 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements, Turkey, Turkey Statements

(Photos: Pen International)

Charges of acquiring and divulging state secrets, membership of, and administration of a terrorist organisation brought against five journalists, including four former members of Taraf newspaper’s editorial and investigative staff, must be dropped and one of the accused, Mehmet Baransu, must be released immediately and unconditionally, PEN International, English PEN, German PEN, Swedish PEN, PEN America, ARTICLE 19, the Committee to Protect Journalists, the European Federation of Journalists, the Ethical Journalism Network, IFEX, Index on Censorship, the International Federation of Journalists, Global Editors Network and Reporters Without Borders said in a joint statement today.

‘These charges are a clear infringement of the right to free expression and a free press in Turkey and must be dropped, and Baransu released. It’s yet another example of abuses by the Turkish authorities of the problematic Anti-Terror law to silence investigative journalists. The law must be reformed without delay,‘ said Carles Torner, Executive Director of PEN International.

The charges concern Taraf editor, Ahmet Altan; deputy editor, Yasemin Çongar; Taraf journalists Mehmet Baransu, Yıldıray Oğur and, a fifth journalist, Tuncay Opçin. All five journalists are facing charges of acquiring and divulging documents concerning the security of the state and its political interests punishable by up to 50 years in prison. Mehmet Baransu and Tuncay Opçin are facing additional charges of ‘membership and administration of a terrorist organization’ and face a possible 75-year prison term.

The charges are detailed in a 276 page indictment, which was accepted on 20 June 2016 by the Istanbul High Criminal Court, 16 months after the initiation of the investigation. Baransu has been held in pre-trial detention since his arrest on 2 March 2015. The journalists’ next hearing is due to be held on 2 September 2016.

The indictments and the materials presented by the prosecutor in relation to the case are open to very serious doubts, suggesting that the charges are politically motivated.

While large parts of the indictment against the journalists focuses on a series of controversial news reports, titled the ‘Balyoz (Sledgehammer) Coup Plan’[1], published in Taraf between 20-29 January 2010, about an alleged military coup to overthrow the Justice and Development Party (AK Party) government, the charges do not, in fact, relate to this story. Indeed, the indictment does not suggest Taraf’s decision to publish the Balyoz papers was criminal and Balyoz does not figure in the specific charges presented at all.

Instead, the indictment brings charges of acquiring and divulging state secrets against the five journalists concerning the ‘Egemen Operation’ plan – an out of date military war plan to respond to a Greek invasion. However Taraf did not publish state secrets regarding this operation, as a prior judgment of the Turkish Constitutional Court affirms.

‘Beyond the simple problem of a lack of evidence, there are serious concerns regarding the indictment which suggest it has been written to obfuscate facts and to implicate the journalists in involvement in the Balyoz case, an already controversial story, to limit public support for their situation,’ said Erol Önderoğlu from Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

Additionally, 46 pages of the indictment prepared against the former Taraf journalists have been copied directly from the indictment against Cumhuriyet journalists, Can Dündar and Erdem Gül, who exposed illegal arms transfers by the Turkish Intelligence Service (MIT) into Syria and were sentenced to prison for five years for this crime. The degree of direct reproduction is evident from the fact that one paragraph of the indictment even starts with the words “The Defendant Can Dündar.”

‘The fact that large parts of the indictment have been copied from another high profile case targeting journalists raises significant concerns about the motivation and professionalism of the Prosecutor: not only does this call into question the extent to which the facts and evidence of the case have been properly examined, it reinforces concerns that the charges may be politically motivated’ said Katie Morris, Head of the Europe and Central Asia Programme at Article 19.

PEN International, English PEN, German PEN, Swedish PEN, PEN America, ARTICLE 19, the Committee to Protect Journalists, the European Federation of Journalists, the Ethical Journalism Network, IFEX, Index on Censorship, the International Federation of Journalists, Global Editors Network and Reporters Without Borders call on the Turkish authorities to immediately and unconditionally release Baransu and to drop all charges that the five journalists face as a result of their work in public interest. Such legal actions against journalists, result in a pervasive ‘’chilling-effect’’ among the rest of the media in the country, which is compounded where fundamental fair trial safeguards are not upheld.

________

[1] These reports were based on a series of classified documents and CDs acquired from an anonymous source. They led to widespread discussion in the country, which prompted Turkish prosecutors to initiate a controversial trial against the alleged coup-plotters named in the documents. The army officers implicated in the alleged coup plot revealed by Taraf have repeatedly claimed that the evidence against them was fabricated. In 2014, Turkey’s highest court ruled that the authorities had violated the officers’ right to a fair trial, leading to fresh hearings and mass releases from prison; including releases for several officers that had previously received sentences of up to 20 years in prison.