27 Apr 2015 | Bosnia, mobile, News and features

Sara, Nataša, Elma and Lejla (clockwise, from top left) are local correspondents for Balkan Diskurs.

At first glance it’s easy to mistake Bosnia and Herzegovina’s media landscape as one of promise. With a constitution that guarantees freedom of the press, a large number of media outlets, and a financially independent regulatory body, the small Balkan country performs relatively well by Southeast European standards.

But on closer inspection such freedoms are a mere façade, hiding this divided, post-war state’s continued struggle with a highly polarised and politicised media. Despite appearances, many of the fundamental aspects of media freedom face significant challenges and, according to recent reports, the situation is only worsening.

Lejla, Nataša, Sara and Elma live their lives within this decline. All in their early to mid-twenties, they represent a generation that had little to do with the war but that bears the burdens of its legacy nonetheless. All four are full-time students, but in their spare time, they’re working towards a fairer, freer future across Bosnia as local correspondents for Balkan Diskurs – a non-profit platform created and run by a regional network of journalists, artists and activists, dedicated to providing objective news (full disclosure: the author of this article works with Balkan Diskurs).

“The media is in the hands of the government. Certain persons dictate which news to publish, how much, and so on,” explains Nataša, from Bijeljina, the second largest city in predominantly Bosnian Serb Republika Srpska, one of the country’s two constituent entities. Sara, from Jajce, confirms that her impression of media within her entity, the predominantly Bosniak and Bosnian Croat Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, is the same: “They should be working for public benefit, [but] they are mostly just an arm of parties and political elites.”

Such criticisms will come as little surprise to those who have been tracking the state of media freedom in Bosnia. Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project, Freedom House and Reporters Without Borders have pointed to mounting levels of political pressure and media partisanship. Such pressure takes a variety of forms, but largely stems from the country’s ongoing ethnic and political cleavages. Many media outlets, including Bosnia’s three public broadcasters, are organised along ethnic lines, while some are either aligned, openly affiliated or funded by specific political parties or figures.

As a consequence, skewed media coverage is commonplace and corruption and crime often goes unreported. As Lejla explains: “Many things happening in Visoko are never reported in media, for reasons unknown to me, and those are not small things either – for example there were multiple shootings last month and very little was written about it.”

Media bias, she added, “is most obvious though when political topics from the Federation and Republika Srpska are compared”.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) is a regular victim of such political bias. Much of the local media coverage of the tribunal is skewed and selective. For example, during the closing days of the case against Radovan Karadžić, the Sarajevo-based Dnevni Avaz focused on the prosecution’s charges against the former Bosnian Serb politician, while Banja Luka-based Nezavisne Novine focused solely on his defense and protestations of innocence. Furthermore, only “a handful” of independent organisations in Republika Srpska are known to report on trials within Bosnia’s local War Crimes Court.

Equally as worrying is the fate of those who resist such political pressures. It is not uncommon for journalists and media outlets in both of Bosnia’s entities to face harassment from political, religious and business leaders. Last December, Republika Srpska’s anti-corruption police raided the Sarajevo headquarters of Klix.ba with the aim of identifying the source of a recording published on the news site. Nor are Bosnia’s regulatory agencies immune, as demonstrated by a spate of unidentified attacks against the country’s press council in 2014.

Political pressure is not the only threat to media in freedom in Bosnia. The country’s deteriorating economic situation also presents serious challenges. “Journalists sell their names for trinkets, I guess due to lack of other options or because they are used to taking the easy way out,” Elma explains. “I have witnessed various manipulations by local ‘wannabe journalists’ who publish every single piece of information that lands in their inbox without checking it, not being aware of the consequences,” she adds.

This thoughtless reproduction of news frequently leads to the rapid spread of false information, as demonstrated by the whirlwind of stories surrounding Bosnia’s protests last spring. This phenomenon is only exacerbated by a strong culture of social media use and low levels of media literacy. “The problem is anyone who has internet access can start their own portal or a Facebook page where they will write whatever they want in anyway they see fit… and many people lack critical thinking,” says Elma.

This sad truth has a silver lining though, and it is one all four women subscribe to through their work with Balkan Diskurs and within their local communities: Bosnia’s citizens also have the potential to change the media landscape. “Thinking with your own head and not being a sponge that soaks up everything that is offered [is important],” claims Elma.

Meanwhile her colleagues underline the promise of independent media in terms of media freedom. “Balkan Diskurs gives my voice an opportunity to be heard, so that stories that others keep quiet about can be told; to present my town in a different, more real light. That opportunity, for me, is priceless,” concludes Lejla.

Balkan Diskurs is a non-profit, multimedia platform created and run by a regional network of journalists, bloggers, multimedia artists, and activists who came together in response to the lack of objective, relevant, invigorating, independent media in the Western Balkans. In partnership with Index on Censorship, the site is supporting efforts to map the state of media freedom in Europe.

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

This article was posted on 27 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

29 Dec 2014 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Politics and Society, United Kingdom, United States

(Photo: David von Blohn/Demotix)

Ben Wizner is a director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Speech, Privacy & Technology Project — which is dedicated to protecting and expanding individuals’ right to privacy, as well as increasing the control that one has over their personal information, ensuring that civil liberties are enhanced, rather than compromised, by new advances in science and technology.

Winzer has litigated numerous cases involving post-9/11 civil liberty abuses. These include challenges to airport security policies, government watchlists, extraordinary rendition, and torture. He has testified before US Congress, and also traveled several times to Guantánamo Bay, where he has met people who have been held against their will in secret prisons and tortured by the CIA.

In July 2013, one month after the revelations about the NSA’s practices came to light, Winzer became Edward Snowden’s attorney. He was put in contact with him directly through the journalist Glenn Greenwald. I spoke to Wizner, focusing specifically on the issue of maintaining democratic accountability as technology advances.

He spoke about why he thinks Snowden’s actions to break the law were justified for the sake of the public interest; why we should be worried about relinquishing our privacy over to a secret state, as well as corporations that keep all of our data to ensure that they can target us on a daily basis with advertisements; and why both Congress and the courts, in the United States, have been weak when it comes to protecting individual privacy of American citizens.

Index: With respect to tracking devices and GPS systems, can you discuss how important location has become for both governments and corporations who now spy on us as citizens?

Winzer: Well think about it in terms of privacy before you think about it from the point of view of power.

The location data is a proxy for so many intimate details of our lives. Governments can use location data to learn if you are gay or straight, who you are sleeping with, whether you are an alcoholic, or if you have medical conditions. That information is even more useful than he content of conversations.

When people are eavesdropping on conversations you can lie and you can use code.

But with meta data people can’t lie. So we have kind of gotten this debate about privacy backwards. People think that content is more sensitive than meta data. But in bulk, meta data is more sensitive than content. If you ask any law enforcement officer if they were given the choice in a single day, of having your phone calls, or having the meta data, they would take the phone calls. But if they were given the phone calls for a month or two months, they would take the meta data.

Index: Is there really a need in your opinion for the surveillance cameras that operate in places like London, which appears to have more security cameras per square foot than almost anywhere in the world? And is there presence really just creating a culture in western society of fear rather than trust?

Winzer: The issues with cameras, as with so many tracking technologies, is that they are sold to the public as one thing but they are actually something else. There is very little evidence to suggest that surveillance cameras will prevent anything like the bombings that London had in its transportation system in 2005.

There is some evidence, however, that surveillance cameras are useful, not as a predictive technology, but as a forensic technology.

In the US, the position that we have tried to take is that there is a difference between a system like London’s, where the government controls a huge set of surveillance cameras and can track an individual across the city in real time. So what had you in Boston after the bombings in 2013, was that cameras helped the FBI figure out who had started that terrorist attack. But there was no centralised system. It was just that all the privately held data was brought together after that emergency in order to solve that crime. So there you had the forensic benefit without the threat of giving the government that much power to track citizens in real time.

What has been interesting in the US is that while most Americans have been supportive of surveillance cameras, they have a very different reaction to surveillance drones. And its worth thinking about why that might be? There are already cameras that can be surmounted on drones that can survey an entire city in real time and record every inch of the public space. And so that seems like a permanent eye in the sky. Whereas I think people have a sense that they can avoid cameras, even if that is not true. But I wonder if citizens in the UK who were enthusiastic about surveillance cameras would feel differently if the authorities were flying surveillance drones around London?

Index: When was the first time you met Edward Snowden?

Winzer: I had never heard his name until the Guardian published the Snowden revelations in June 2013. The first time that we interacted over an encrypted chat programme was in July of 2013. The first time we met face to face was in Moscow in January of 2014. And by that time we were old friends, having communicated on almost a daily basis for almost six months.

Index: Are you confident that you can get him back to the United States as a free man?

Winzer: It’s certainly the goal to get him back to the United States with dignity and freedom. The second goal would be to get him to a country in Europe or somewhere else. But in the meantime his morale is high. And his life is not so different than if he were living in another country. He spends his days in Moscow for the most part surrounded by computer screens, consuming information, communicating with journalists, lawyers, and participating in the public debate. And before long I think we will see him getting back to work as an engineer and a computer scientist creating tools to make mass surveillance more difficult and to protect privacy. But wherever he lives in the world he wants a very private life. He is someone who would prefer to be anonymous and in the shadows. The good news is that he is still living in freedom and because of technology he is able to participate meaningfully in the public debate.

Index: Can you speak about your experience in the pre Snowden era when the ACLU(American Civil Liberties Union) tried to challenge these illegal spying programmes by the NSA in open courts: did the the US government and US courts say that you didn’t have legal standings to peruse these legal challenges?

And how did the actions of Edward Snowden change that?

Winzer: Snowden’s actions did change a lot. One of the questions he asked me during our first conversation was: do you now have standing to bring these cases? Because he had watched how our challenge to surveillance programmes were thrown out. Not because the courts said the programmes were legal, but because they said that the programmes had no right to be in court. I spent a lot of time representing those who were victims of the Bush Administration’s torture conspiracy: people who were kidnapped off the street and held by the CIA and tortured. And every one of those cases was thrown out on grounds of state secrecy.

So I did not have a lot of confidence in the courts from the moment that Snowden arrived. But now I think the atmosphere around these judicial decisions has changed considerably.

Index: Why have Congress and the courts been so weak in the US thus far on this matter?

Winzer: Well one reason is that the military surveillance-industrial-complex is massively powerful and corrupt.

And if you track campaign donations, you will see that members of Congress who sit on intelligence committees get massively higher campaign donations from the community that they are supposed to regulate: the surveillance and defence contractors who are doing this work. That creates a situation where the people who are most sceptical, are in fact most deferential. But there is political expedience. Who in Congress after 9/11 wanted to be the person who would say: I think the NSA and CIA are going too far.When the Patriot Act legislation was rushed through congress, the vote in the senate was 98 to 1.

So the politics of national security can be very toxic in the US.

Index: And is it the same situation in the courts do you believe?

Winzer: Yes. Imagine, for example, you are a judge, and you are considering a law suit about surveillance or torture. And somebody comes to your chambers from the Department of Justice with a brief case handcuffed to his wrist. And inside it is a secret deceleration from the head of CIA, which says: your honour with all due respect, if you allow this case to go ahead you are going to be responsible for all grave harm to national security. I think most judges in that situation would rather kick the case up stairs. If the judges are going to be involved, let the Supreme Court do it. And many of them have so much respect for the national security officials who are writing those declarations.

Index: But like Congress, the courts are responsive to the public mood, right?

Winzer: Well since Snowden, we have seem judges who are much more willing to stand up to the government arguments. We’ve seen one court say that the NSA’s meta data collection programme was unconstitutional and almost Orwellian. So our Supreme Court is not apolitical. This is tremendous power on the government’s side that is consolidated in one branch of government. And so it’s very easy to see scenarios that would be grave threats to democracy.Some of the them sound paranoid. For example, what if someone in the executive branch wanted to blackmail the justice of the Supreme Court. That would be a trivial matter to do. What prevents it are internal policies and laws. And you have to have a lot of confidence in those policies and laws. And so this is why people use the term data bases of ruin. If we collect these massive amounts of information we really are sitting on a ticking time bomb. And we might be confident that it’s never going to blow up. But we have to be sure that we are making our right way to the future.

Index: Given that we now live in a world where nothing is permanently delated, and where everything is stored in a digital cloud: do you think it’s time there are the same legal protections for email that there is for normal mail? And have the ACLU been doing anything to try and ensure that this happens?

Winzer: We have reached a point where, for the most part, we are there with email. All of the major email providers in the US refuse to disclose email content to law enforcement without a warrant. There is not a lot of case law on this, because the government has been very careful to avoid having courts decide this question, they drop appeals, rather than litigating the question. The federal law that governs law enforcement access to emails is from 1986, before there was a World Wide Web.

And that is wildly out of date. So we do need to update that. But there is all other kinds of information that gets stored in a digital cloud.

Index: Can you explain The Third Party Doctrine and how that affects the rights of US citizens, in terms of giving away their privacy?

Winzer: With The Third Party Doctrine the government basically argues that if we provide that information to a third party— a cloud service for example— that our Fourth Amendment [our right to privacy under the US Constitution] is waived. So that is the argument that government makes to defend the constitutionality of the NSA collecting the meta data of all phone calls that happen every day. Their argument is that by simply dialling the number, you have shared it, with say, for example, the telephone company Verizon, and therefore you can’t claim that the constitution prevents the government from having that same access.

This argument made no sense in the 1970s and it certainly makes no sense today, where the government is not collecting phone numbers from one person’s phone calls, but from everybody’s phone calls, every day. The difference in degree amounts to a difference in kind. It’s not just a question of scale, it’s a completely different surveillance activity. Again, it’s really about how advances in technology should not diminish our rights. We should essentially use the models that we developed for the analogue world in figuring out what legal protections we are going to need in the digital world.

Index: Are the laws in the US, with regards to privacy, woefully inadequate?

Winzer: Yes. But there has been a lot of momentum and progress. And now we are seeing a handful of US states that have passed laws: these say that the government needs a warrant before it can get your location from a phone company. So there is a more broad coalition for privacy protection. And we are seeing progress in the courts. In the last two years we have seen two unanimous decisions in the Supreme Courts, one where law enforcement ruled that if they cease your cell phone during your arrest they have to get a warrant before they search it.

The second is that they said they have to get a Fourth Amendment search for the government to use GPS to track you over time. There is a lot of momentum in the US towards some of the kind of changes that are necessary. It would be much harder to implement those changes with respect to spy agencies like the NSA. So far we have made a lot more progress in restraining law enforcements. But again most Americans are more likely to have interactions with spy agencies.

Index: Where does one draw the line between a certain amount of secrecy to protect the national interest of a nation for security purposes, and then something that boarders on a totalitarian government. And at the moment is the US government in the latter category?

Winzer: The problem of secrecy in a democracy is a very old one. We need to ask what happens when there is a conflict between self rule and self defence?Even in a democracy most of us believe that there are some legitimate secrets that have to do with national defence. So how do you bridge that gap? For the most part I think the way in which we have tried to bridge that gap has failed. We have intelligent committees in Congress that is supposed to rigorous oversight on behalf of all of us. But too often those members of Congress are most likely to rubber stamp and cheerlead for the intelligence agencies, rather than subjecting them to scrutiny.

Courts in the US for a long time now have not wanted to get their hands dirty on issues of national security. And more often than not they defer to the executive branch by saying that they are not experts on these issues. So for the ACLU, one of the very important safety-valves has been whistle blowers and a free press. There is never going to be a neat structural solution to the oversight programmes in democracies. It’s going to be a constant struggle. We need the Edward Snowden’s of this world and the hundreds of leakers whose names are never known. But who provide access that appears everyday in newspapers.

Index: How can we differentiate between government’s and companies spying on citizens. And which is worse in the long term?

Winzer: We need to understand what is at stake with each kind of collection. Sometimes they are linked.

To the extent that the government is able to get information from the companies. But in general governments have powers that corporations don’t have. Governments can take away your liberty and your life. They can target drone strikes. They can lock you up. So traditional civil libertarians and human rights activists are concerned about government surveillance programmes. Mainly because that is where the democratic harms occur and where people can lose their core rights.

Index: Since the Snowden revelations have come out: what do you think we have learned about the relationship between privacy and technology that we may have not have fully understood as a society before them?

Winzer: I would break up that “we” into two different groups. The various technology groups learned that their worst fears about government surveillance were not even close to what was actually going on. That the NSA and its partners far exceed what they knew was going on. And it woke them up to the actual threat model. And I hope what the general public has absorbed from the Ed Snowden affair is that we were asleep at the wheel. Now it wasn’t our fault. Our government didn’t only conceal this information from us they actively lied to us about it. Which is why I think Snowden was justified in doing what he did. But we now need to be much more active citizens in a democracy if we don’t want our society to be created in secret by spy agencies.

Index: What is your response to those who say that Edward Snowden is a traitor to the American people?

Winzer: People who believe that are not persuadable anyway. These are people who have spent their careers indoctrinated in the defence and intelligence agencies. In their view, he took upon himself to do this and the result of that was so damaging to their public reputations around the world. These are people who don’t consider themselves to be evil actors, but solid citizens and good bureaucrats. There has been times in our history, when it is necessary to break the law in order to vindicate it. For example in the founding of the United States, where people threw tea into Boston Harbour, to more recently in 1971 when a bunch of anti-war activists broke into an FBI office in Pennsylvania and stole all of the FBI files: leading to one of the most important periods of reform in the country’s history.

Index: So are people wrong to question Snowden’s judgment?

Winzer: People are free to question Edward Snowden’s judgment. But I hope by now they don’t question his motivations. He acted in every way that the public interest by setting guidelines for what they should and should not publish from the material. I believe he behaved in the most reasonable way that he could in these circumstances.

Moreover, I wonder would those people question the patriotism of our national security, people who went before our Congress and not only concealed from the public what they were doing, but also lied under oath about what they were doing. I wonder would those same people question the patriotism of the traditional oversight bodies that essentially didn’t do their job between the period between 9/11 and now.

Most people, including President Obama, have said that the debate we are having here in the US about privacy is an important one that will make us stronger. And there is no way that this debate would have happened without Edward Snowden’s actions.

This article was posted on Dec 29 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Jun 2014 | Brazil, Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Statements, News and features

This is the third in a series of articles based on the Index report: Brazil: A new global internet referee?

Key debates are under way at international level on internet governance, with crucial decisions up for grabs that could determine whether the internet remains a broadly free and open space, with a bottom up approach to its operation – as exemplified in part by the multistakeholder approach – or becomes a top-down controlled space as pushed for by China and Russia, supported to some extent by several other countries.

In September 2013, the outrage following the revelations of mass surveillance by the US and UK led President Dilma Rousseff to announce that Brazil would host an international summit – NETmundial – on the future of internet governance in April 2014. This internet governance summit – progressive in appearance – took place just two years after Brazil voted in line with countries that have a tradition of internet control at a major international conference on telecommunications in Dubai.

This section looks at Brazil’s attitude in global internet governance debates and the potential contradictions between its domestic and foreign internet policies. In the aftermath of NETmundial and a year before Brazil is to host the 2015 Internet Governance Forum (IGF), this chapter also looks at Brazil’s ability to impose itself as a world leader in internet governance debates.

Is Brazil a swing state on global internet governance? Contradictions between domestic and international policies

What is at stake during the international discussions that shape the evolution and use of the internet has implications for all. The current multistakeholder approach for internet governance supposedly includes civil society and non-governmental actors in decision-making. It is a more bottom-up and multi-layered process, allowing a range of organisations to determine or contribute towards different parts of internet governance. The consultation process at the origin of the Marco Civil law is a possible example of the multistakeholder approach in action: Civil society, private companies, academics, law enforcement officials and politicians participated in the draft.

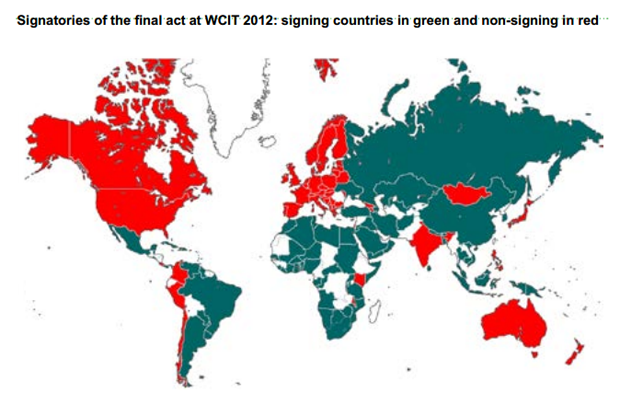

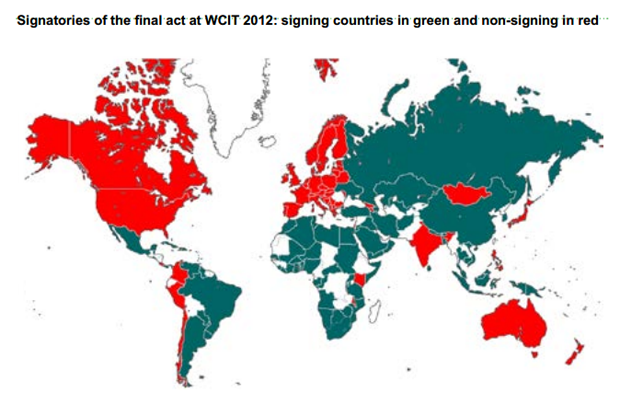

While Brazil has been pushing for stronger internet freedoms lately, especially at the domestic level, it has a history of going in the other direction. In December 2012, Brazil aligned with a top-down approach lobbied by countries that have a tradition of internet control at the Dubai World Conference on International Telecommunications (WCIT) summit. This meeting brought together 193 member states of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in part to decide whether or not and how the ITU should regulate the internet. On one side, EU member states and the US argued the internet should remain governed by an open and collaborative multistakeholder approach. On the other side of the divide, Russia, China and Iran lobbied for greater government control of the net. Brazil, along with the most influential emerging democratic powers (India the notable exception), aligned with this top-down approach.

This decision appeared in total contradiction with Brazil’s defence and implementation of the multistakeholder model at home with Marco Civil (see previous section on Marco Civil da Internet). At the time, the rapporteur of Marco Civil, Alessandro Molon, was opposed to the new ITU regulations and regretted that Marco Civil had not been adopted before the vote. While it is not unusual for any government to see a contradiction between domestic and foreign policy, Molon believed that the adoption of Marco Civil would have established without doubt Brazil’s policy and support for a transparent and inclusive approach to internet governance.

The reasons behind Brazil’s vote at the WCIT are obscure. First of all it is worth noting that most Latin American countries voted in favour of the text adopting new International Telecommunications Regulations. An analysis of the region’s vote shows that beyond governments’ intentions and goodwill towards the current multistakeholder governance model, to most Latin American governments, the new regulations were not about the internet but about telecommunications. Most of these governments would have looked at the new ITRs to “reap some of the benefits of the ITRs as a whole”, especially in terms of technical facilities. Second, like India, Brazil has increasingly expressed its desire to take on the US hegemony over the internet and digital technologies. The clash between the two sides revealed at WCIT 2012 led The Economist to call WCIT 2012 a “digital cold war”. Brazil’s position is, however, more complex. Neither a supporter of the US nor Sino-Russian initiatives, Brazil has been seeking greater recognition in multilateral forums and has called for the rebalancing of international institutions. As one of the new global economic powerhouses alongside Russia, India and China, but considered the most democratic of that group with India, aligning with countries supporting tighter government control was more a statement against internet governance by institutions seen as under US control – namely ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) – and an assertion of Brazil’s sovereignty.

The revelations on mass surveillance activities carried out by the US further fuelled Brazil’s will to break from US-centric internet. Standing against mass surveillance, Brazil distanced itself from the top-down internet governance approach and called for an “open, multilateral and democratic governance, carried out with transparency by stimulating collective creativity and the participation of society, governments and the private sector.”

Shortly after announcing the organisation of an international conference to discuss the future of internet governance in response to the surveillance revelations, President Dilma Rousseff also ordered a series of measures aimed at greater Brazilian online independence and security. But what are the internet governance implications of that opposition to the US spying? By trying to get away from the US dominance of the internet, Roussef’s measures risk taking a regressive stance on the internet. Paradoxically, while asserting internet freedoms, the geopolitics behind Brazil’s response to mass surveillance could align it with countries pushing for top-down internet control both nationally and internationally.

After Snowden: Brazil taking the lead and opposing mass surveillance – but at what cost?

In September 2013, President Dilma Rousseff made a strong political response to Snowden’s revelations on mass surveillance activities carried out by the United States. In a speech delivered to the UN General Assembly, Brazil’s president accused the NSA of violating international law and called on the UN to oversee a new legal system to govern the internet. Rousseff seized the momentum created by Snowden’s revelations to question the current multilateral mechanisms in place – such as ICANN – and announced that Brazil would host an international summit to discuss the future of internet governance in April 2014: NETmundial. ICANN has faced growing criticism in recent years about the influence of the US government on its operations. In this context, the efforts of Brazil in promoting digital freedom at domestic level with Marco Civil have helped the country gain a leading role and visibility in internet rights discussions. While India used to appear as a natural leader of the debate, discussions on Marco Civil and internet legislation have reached an international audience to the extent that Indian politicians now say “India has lost its leadership status to Brazil in the internet governance space”.

Not only is Brazil one of the countries with emerging influence in the multipolar world but it is also a state whose population is increasingly engaging with the internet. The decision to host NETmundial shows both Brazil’s stand against mass surveillance – at least officially – and its ambition to take the lead on internet governance debates.

The opposition to US-led mass surveillance led Brazil to propose a series of ambitious and controversial measures aimed at extricating the internet in Brazil from the influence of the US and its tech giants, in particular protecting Brazilians from the reach of the NSA. These included: constructing submarine cables that do not route through the US, building internet exchange points in Brazil, creating an encrypted email service through the state postal system and having Facebook, Google and other companies store data by Brazilians on servers in Brazil. While the first two were an attempt at developing internet infrastructure in Brazil, forcing tech giants to locate their data centres locally to process local communications would have big implications. Not only would it be very difficult to implement at a practical level, but it would not even protect Brazilians’ data from surveillance. On the contrary, data stored locally would be more vulnerable to domestic surveillance. This proposal – even made with good intent – was sending the wrong message, especially to other countries looking to Brazil as a leader in this space. Engineers and web companies, who have their own agenda and economic interests, argued it would have a negative impact on Brazilian competitiveness, would be damaging for its tech sector and pose a threat of “internet fragmentation”. In terms of internet freedom, the measure set a dangerous precedent. Indeed, forced localisation of data relates more to measures undertaken by countries that have a reputation of internet control and repressive digital environments, such as China, Iran and Bahrain.

At a time when Brazil is gaining international exposure for defending internet freedom, it is important to stick to a progressive internet governance approach, including at the international level. The international summit on the future of internet governance – NETmundial – kicked off with Brazil reiterating its commitment to a “democratic, free and pluralistic” internet. The signing of Marco Civil da Internet into law by the Brazilian president onstage set the tone of the event: “The internet we want is only possible in a scenario where human rights are respected. Particularly the right to privacy and to one’s freedom of expression,” said Dilma Rousseff in her opening speech. She added about Marco Civil: “As such, the law clearly shows the feasibility and success of open multisectoral discussions as well as the innovative use of the internet as part of ongoing discussions as a tool and an interactive discussion platform”.

The drafting process of Marco Civil and the inclusive consultation process that has involved civil society and private sector from beginning to end served as a model for the organisation of NETmundial. The unprecedented gathering brought together 1,229 participants from 97 countries. The meeting included representatives of governments, the private sector, civil society, the technical community and academics. Remote participation hubs were set up in cities around the world and the NETmundial website offered an online livecast of the meetings.

However, despite efforts to include civil society and despite Dilma Rousseff’s speech in favour of freedoms online and net neutrality, the geopolitics around the event and pressure from some governments and private sector led to a weak, disappointing outcome document. The final version of the “Internet governance principles” document did not even mention net neutrality – a fundamental principle of the internet architecture. Disappointed and frustrated, many internet activists launched a campaign asking governments to take concrete actions to end global mass surveillance and protect the free internet. Some even came to question the multistakeholder model of internet governance.

The multistakeholder model in question

Although the process for discussion adopted by NETmundial appeared inclusive, the multistakeholder model was criticised by internet activists and described as “oppressive, determined by political and market interests”. The balance of power and weak outcome document of NETmundial led them to call the principles of NETmundial “empty of content and devoid of real power”. La Quadrature du Net, which defends the rights and freedom of citizens on the web, called NETmundial international governance a “farce” and the multistakeholder approach an “illusion”.

Although Brazil made considerable efforts to offer an event open to civil society, academics, private sector and all governments, in reality the power of non-government actors, especially of civil society, is relatively weak next to the dominance of governments, tech giants and other powerful private corporations. And, as attractive as the rhetoric of liberty and freedom might be, intrusive governance is still regarded as acceptable by governments of all kinds – even those with apparently progressive attitudes towards an open internet. This is reinforced by fears of virtual crimes and cybersecurity, which are vital areas of government policy, as recently claimed by the Brazilian minister of communications Paulo Bernardo. In Brazil, as well as in India and other democracies, the balance between freedom and security can generate contradictory positions between international and domestic policies, and security arguments have often been used to justify claims for greater state control over critical internet resources, at the risk of falling into the game of repressive regimes.

The future of internet governance is still being discussed and Brazil is under the spotlight. It is not clear yet to what extent Marco Civil will lead to a safer and better online and offline environment. Meanwhile, Brazil should not support approaches that lead to top-down control of the net or forced local hosting of data. In the aftermath of NETmundial, Brazil appears more as a leader and influencer in the global debates on the future of internet governance. However, the outcome of NETmundial underlined Brazil’s vulnerability to pressure from the US, the EU and industrial interests. Brazil must continue to build on Marco Civil in the international sphere and use its clout to promote internet freedoms.

The full report is available in PDF: [English] | [Portuguese]

Part 1 Towards an internet “bill of rights” | Part 2 Digital access and inclusion | Part 3 Brazil taking the lead in international debates about internet governance | Part 4 Conclusions and recommendations

This article was posted on 16 June 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

![Read the full report in PDF: [English] | [Portuguese]](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/brazil-cover.jpg)