Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

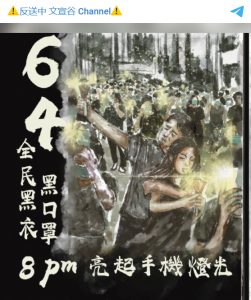

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

It shows crowds of young Hong Kongers, all dressed in black, at a protest, holding their smartphones aloft like virtual cigarette lighters from a Telegram channel called HKerschedule.

The image is an invitation for young activists to congregate and march to mark the anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre on 4 June. Wearing black has been a form of protest for many years, which has led to suggestions that the authorities may arrest anyone doing so.

Calls to action like this have migrated from fly posters and other highly visible methods of communication online.

Secure messaging has become vital to organising protests against an oppressive state.

Many protest groups have used the encrypted service Telegram to schedule and plan demonstrations and marches. Countries across the world have attempted to ban it, with limited levels of success. Vladimir Putin’s Russia tried and failed, the regimes of China and Iran have come closest to eradicating its influence in their respective states.

Telegram, and other encrypted messaging services, are crucial for those intending to organise protests in countries where there is a severe crackdown on free speech. Myanmar, Belarus and Hong Kong have all seen people relying on the services.

It also means that news sites who have had their websites blocked, such as in the case of news website Tut.by in Belarus, or broadcaster Mizzima in Myanmar, have a safe and secure platform to broadcast from, should they so choose.

Belarusian freelance journalist Yauhen Merkis, who wrote for the most recent edition of the magazine, said such services were vital for both journalists and regular civilians.

“The importance of Telegram has grown in Belarus especially due to the blocking of the main news websites and problems accessing other social media platforms such as VK, OK and Facebook after August 2020,” he said.

“Telegram is easy to use, allows you to read the main news even in times of internet access restrictions, it’s a good platform to quickly share photos and videos and for regular users too: via Telegram-bots you could send a file to the editors of a particular Telegram channel in a second directly from a protest action, for example.”

The appeal, then, revolves around the safety of its usage, as well as access to well-sourced information from journalists.

In 2020, the Mobilise project set out to “analyse the micro-foundations of out-migration and mass protest”. In Belarus, it found that Telegram was the most trusted news source among the protesters taking part in the early stages of the demonstrations in the country that arose in August 2020, when President Alexander Lukashenko won a fifth term in office amidst an election result that was widely disputed.

But there are questions over its safety. Cooper Quintin, senior security researcher of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a non-profit that aims to protect privacy online, said Telegram’s encryption “falls short”.

“End-to-end encryption is extremely important for everyone in the world, not just activists and journalists but regular people as well. Unfortunately, Telegram’s end-to-end encryption falls short in a couple of key areas. Firstly, end-to-end encryption isn’t enabled by default meaning that your conversations could be intercepted or recovered by a state-level actor if you don’t enable this, which most users are not aware of. Secondly, group conversations in Telegram are never encrypted [using end-to-end encryption], lacking even the option to do so, unlike other encrypted chat apps such as Signal, Wire, and Keybase.”

A Telegram spokesperson said: “Everything sent over Telegram is encrypted including messages sent in groups and posted to channels.”

This is true; however, messages sent using anything other than Secret Chats use so-called client-server/server-client encryption and are stored encrypted in Telegram’s cloud, allowing access to the messages if you lose your device, for example.

The platform says this means that messages can be securely backed up.

“We opted for a third approach by offering two distinct types of chats. Telegram disables default system backups and provides all users with an integrated security-focused backup solution in the form of Cloud Chats. Meanwhile, the separate entity of Secret Chats gives you full control over the data you do not want to be stored. This allows Telegram to be widely adopted in broad circles, not just by activists and dissidents, so that the simple fact of using Telegram does not mark users as targets for heightened surveillance in certain countries,” the company says in its FAQs.

The spokesperson said, “Telegram’s unique mix of end-to-end encryption and secure client-server encryption allows for the huge groups and channels that have made decentralized protests possible. Telegram’s end-to-end encrypted Secret Chats allow for an extra layer of security for those who are willing to accept the drawbacks of end-to-end encryption.”

If the app’s level of safety is up for debate, its impact and reach is less so.

Authorities are aware of the reach the app has and the level of influence its users can have. Roman Protasevich, the journalist currently detained in his home state after his flight from Greece to Lithuania was forcibly diverted to Minsk after entering Belarusian airspace, was working for Telegram channel Belamova. He previously co-founded and ran the Telegram channel Nexta Live, pictured.

Nexta’s Telegram page

Social media channels other than Telegram are easier to ban; Telegram access does not require a VPN, meaning even if governments choose to shut down internet providers, as the regimes in Myanmar and Belarus have done, access can be granted via mobile data. Mobile data is also targeted, but perhaps a problem easier to get around with alternative SIM cards from neighbouring countries.

People in Myanmar, for instance, have been known to use Thai SIM cards.

The site isn’t without controversy, however. Its very nature means it is a natural home for illicit activity such as revenge porn and use by extremists and terror groups. It is this that governments point to when trying to limit its reach.

China’s National Security Law attempts to censor information on the basis of criminalising any act of secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with external forces, the threshold for which is extremely low. It has a particular impact on protesters in Hong Kong. Telegram was therefore an easy target.

In July 2020, Telegram refused to comply with Chinese authorities attempting to gain access to user data. As they told the Hong Kong Free Press at the time: “Telegram does not intend to process any data requests related to its Hong Kong users until an international consensus is reached in relation to the ongoing political changes in the city.”

Telegram continues to resist calls to share information (which other companies have done): it even took the step of removing mobile numbers from its service, for fear of its users being identified.

Anyone who values freedom of expression and the right to protest should resist calls for messaging platforms like Telegram to pull back on encryption or to install back doors for governments. When authoritarian regimes are cracking down on independent media more than ever, platforms like these are often the only way for protests to be heard

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116804″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]The diversion of a Ryanair plane to Minsk over the weekend on the orders of Belaruisan president Alexander Lukashenko and the subsequent detention of independent journalist Roman Protasevich is the latest incident in a clampdown on independent media in the country.

Protasevich, working for Telegram channel Belamova, has been living in exile in Poland and Lithuania since 2019 because of concerns for his safety. His name appears on the List of Organizations and Individuals Involved in Terrorist Activities published by the State Security Committee (KGB), an includion which led him to referring to himself as “the first ever terrorist journalist” on his Twitter account.

Belarusian citizens increasingly have to go to independent media outlets such as Belamova, Nexta, Tut.by and others to find out the truth about what is happening in their country.An opinion poll conducted by Chatham House and released in February 2021 found that independent were by far the most trusted media.

As a result, president Alexander Lukashenko wants them shut down.

It is clear from the actions against Protasevich and others that the Belarusian authorities are trying to silence dissenting voices, constantly increasing the level of pressure on independent press representatives and grossly violating the right of their citizens to information. In official discourse, there are constant references to the “information war” against the state.

This latest actions of the Lukashenko regime ramps up what was already unprecedented pressure on the country’s journalists. RSF’s World Press Freedom Index shows that Belarus is Europe’s most dangerous country for those working in the media.

According to data from the Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ), there were more than 480 arrests of journalists in 2020. In 62 of these cases, journalists said they were subject to violence, including some cases of torture. In Minsk, at least three journalists were injured by rubber bullets as a result of police using firearms against peaceful protesters. Since the beginning of 2021, there have been 64 arrests, 38 searches and 5 attacks.

These figures represent the industrial scale judicial prosecution of journalists producing independent coverage of post-election developments in Belarus. Many have been sentenced to short jail terms or have been fined, some of them several times.

In 2020, Belarusian judges sentenced journalists in 97 cases to short jail terms (so-called ‘administrative arrests’), ranging from three to fifteen days. They are typically charged with alleged ‘participation in an unsanctioned demonstration or disobeying police’. Journalists report that the conditions of detention are inhumane – it is very cold, the lights are constantly left switched on, there is a lack of bed linen and hygiene items; many have to sleep on the floor.

A number of journalists are being held under more serious criminal charges simply for doing their job: three journalists have already been convicted.

The journalist Katsiaryna Barysevich, of influential online outlet Tut.by, was tried along with whistleblower doctor Artsyom Sarokin. Sarokin was given a fine and a suspended sentence of two years’ imprisonment. Barysevich was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment. In Barysevich’s case, the reason given was alleged ‘disclosure of confidential medical information causing grave consequences’ under the criminal code. She had published an exposé into a cover-up of the death of peaceful protester Raman Bandarenka.

The other two journalists, Belsat TV journalists Katsiaryna Andreyeva and Daria Chultsova, have been sentenced to two years in prison for supposedly ‘organising actions that grossly violate public order’. Andreyeva and Chultsova conducted a live broadcast of the violent dispersal of peaceful protesters paying tribute to Bandarenka in his neighbourhood.

On 16 February this year, the police raided the apartments of BAJ deputy chairs Aleh Aheyeu and Barys Haretski, along with at least six more BAJ members in different cities. They were investigating a criminal offence of ‘organising and preparing activities that grossly violate public order, or actively participating in them’. The BAJ office was searched and then closed by the police for almost a month.

As I write, there are 34 journalists and media workers behind bars being prosecuted for exercising their right to freedom of expression.

Of that number, 15 were detained by the Belarusian authorities after they began an unprecedented attack on Tut.by, Belarus’ most influential independent news website, on 18 May. The Belarusian Financial Investigation Department (DFR) launched a criminal case against Tut.by staff members for “large-scale tax evasion”, sending its agents to search the Tut.by editorial office in Minsk and its regional branches. The offices of related companies Hoster.by, Av.by, and Rabota.by in Minsk have been also raided. Investigators have also targeted the homes of a number of Tut.by journalists who work for the website and other staff members interrogated.

On the same day, the Ministry of Information of the Republic of Belarus blocked Tut.by and its mirror sites. The decision was taken on the basis of a notification from the General Prosecutor’s Office, which had established ‘numerous facts of violations of the Law on Mass Media’ and, specifically, the publication of materials coming from the Bysol Foundation, an unregistered fundraising initiative in support of victims of political repression in Belarus. Belarusian legislation prohibits the media from disseminating materials on behalf of unregistered organisations.

On 21 May, during an online press conference, Tut.by co-founder Kirill Voloshin, said: “At the moment we cannot restore the portal in the form of a mirror. The reason is that employees and owners do not have access to servers; there are no backups.”

Tut.by is one of more than 80 independent information websites blocked by the Ministry of Information since August 2020. Despite this, most of them continue to play a role in informing Belarusian citizens. Tut.by continues its work on social media and through two Telegram channels.

A number of journalists have been forced to flee Belarus but continue to work from abroad. Freelance journalist Anton Surapin is among them, who was recognised by Amnesty International as the “most absurd political prisoner” in the world in 2012 for his part in the so-called “teddy bears case” – a publicity stunt which saw stuffed bears dropped from a plane to draw attention to freedom of expression restrictions in the country.

When asked about the reasons for his departure, Surapin said: “I believe that now in Belarus there is a simply catastrophic situation in the field of human rights in general, and for journalists in particular. My colleagues are shot at, they are hunted by the security forces, they are imprisoned and deprived of their constitutional right to carry out professional activities.”

The barely credible seizure of Protasevich is not just about silencing him as a journalist – it is a message from Lukashenko that all dissenting voices in the independent media are fair game.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”172″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

There has rightly been international condemnation of the arrest of Roman Protasevich after his Ryanair flight from Greece to Lithuania was diverted to Belarusian capital Minsk. It is of particular concern that the state hijacking of Flight FR4978 was carried out on the personal orders of President Alexander Lukashenko. His disgraceful “confession” on state TV comes straight from the authoritarian playbook.

The 26-year-old has been described in a single report on the BBC as a “Belarusian opposition journalist”, a “dissident” and an “activist”. This extraordinary young man is all these things and more. But it is important that the western media does not let the Belarus regime define the narrative.

Protasevich is an independent journalist, but to be so in Belarus is to immediately become an activist. And, meanwhile, the regime is in the process of defining all activists as terrorists. Index has been reporting for months on the systematic crackdown on independent journalism by the Lukashenko regime. Hijacking is just the latest method to control free expression in Belarus.

British MP Tom Tugendhat (chair of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee) has described the arrest as a “warlike act”, and this is no understatement. He has emphasised that a hijacking is an escalation of the situation. But we should not lose sight of why Protasevich represented such a threat. It is because he was a journalist the regime has not been able to control since he fled the country for Poland in 2019.

Protasevich is the former editor of Nexta, a media organisation that works via the social media platfrom Telegram, which circumvents censorship in Belarus. Nexta was instrumental in reporting on the opposition to Lukashenko during the elections of 2020. Until this week Protasevich had been working for another Telegram channel Belamova. Like the underground “samizdat” publications of the Soviet era, these Telegram channels provided much-needed hope to civil society in Belarus.

Parallels have been drawn between Russian dissident Alexei Navalny and Roman Protasevich and it is true that he provides a similar focus for the Belarusian opposition. However, he has been targeted not as a political leader, but as a journalist. It is as a journalist that we should defend him.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”172″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114603″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]“As long as you don’t kill me, new elections won’t happen,” Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko told workers at the MKZT truck factory in Minsk, the capital city of Belarus last week.

The speech followed a presidential election on 9 August in which Lukashenko claims to have won a landslide victory to serve for a sixth term with just over 80% of the vote, a result heavily contested domestically and internationally. Mass anti-Lukashenko protests have been held across Belarus since the results, with many people saying the result was fraudulent and a result of vote-rigging, while the UK government does not recognise the result and The Council of EU stated that the election was “neither free nor fair”.

Belarus has been ruled by Lukashenko since 1994, after he became the country’s first president in the wake of Belarusian independence from the USSR in 1991. He rules the country with an iron fist; Belarus is the last country in Europe which still uses the death penalty, and many forms of freedom of expression are tightly governed. The state controls the media to the extent that Belarus is ranked at 153 out of 180 countries on the World Press Freedom Index, one of the lowest rankings in the world, not just in Europe. How did a country, freed from the grips of Soviet Union and starting afresh with a new constitution, end up ruled by a man internationally dubbed as “the last dictator in Europe”?

Two years into his presidency, Lukashenko set about dismantling the aspects of the constitution which would have allowed for genuine democracy. In 1996 he demanded a referendum which asked the public to vote on extending his first term from five to seven years and to increase his powers. After the vote went in his favour (although the international community questioned the validity of the result), Lukashenko dissolved the elected Supreme Soviet parliament, who had resisted the referendum, and installed a handpicked collection of loyalists to hold seats in government, effectively wiping out any political opposition and obstacles to authoritarian control.

Another referendum in 2004 took Lukashenko’s desire to retain presidency a step further. Nearing the end of his second term, the maximum number allowed by the constitution, a referendum was held which asked the public to allow him to run a third time. When this passed with an apparent large majority, the limit on the number of terms a president could sit was essentially abolished and Lukeshenko’s grip on power tightened.

In the years between these two pivotal moments in Belarusian history, Index reported from the ground in Belarus about the deterioration of freedom of expression under an evermore authoritarian regime.

A 1997 Index article chronicling attacks on freedom of expression around the world reported that Belarusian journalist Pavel Sheremet was still in the hands of the Belurusian KGB. A “vocal critic of Lukashenko’s government”, Sheremet had previously been stripped of his journalist accreditation for “insulting the ‘president and nation of Belarus’.” Fifteen journalists who picketed for his release were also arrested and detained in a clear signal to the citizens of Belarus: any form of dissent, or support of a dissenter, would be aggressively crushed.

A 1999 report by Michael Foley confirmed this trend; he found that journalists in Minsk were worse off than those in any other former Soviet state. Just five years into Lukashenko’s rule, Foley reported that “the electronic media is almost totally state-owned and the print media is forced to use state owned printing plants”.

As Lukashenko won the election in 2006, securing a third term that never should have been, human rights and freedom of expression in Belarus continued to deteriorate.

LGBTQ rights were and continue to be all but non-existent, with gay marriage constitutionally banned and few legal protections afforded to LGBTQ people. Freedom of assembly has been violated by the authorities’ attempts to prevent Gay Pride events from taking place. A 2000 parade was banned by authorities just hours before the fact, and in 2006 a conference on human rights and gay culture was cancelled after its organisers were arrested.

In 2011, months after Lukashenko’s fourth election victory, James Kirchick reported for Index from Minsk that the regime still had a grip on the media: “the Lukashenko regime has effectively rendered political opposition moot through its near domination of the press. It has silenced critical voices through two means: state control of mass media outlets like television and radio, and onerous registration laws that make the practice of independent journalism a dangerous pursuit”.

In the 10 years since the 2010 election, there has been another election, taking place in this landscape that is weighed heavily in Lukashenko’s favour. As Andrei Aliaksandrau reported for Index in 2017, TV stations continue to be state-owned and Lukashenko continues to rule as a dictator. The 2015 election, similarly to those preceding it, was dogged by controversy and suggestions of an undemocratic process. “The [2015] election process was orchestrated, and the result was preordained”, said Miklós Haraszti, The United Nations Special Rapporteur on human rights in Belarus.

The 2020 election result has seen scenes of protest unlike Belarus has experienced before. After 26 years of propaganda and authoritarian leadership, Belarusians appear to be prepared to tolerate it no longer. Journalists have gone on strike, refusing to be used as propaganda tools. Lukashenko shut down the internet across most of the country in the days following the election, in an attempt to quash dissent, and horrific accounts of intimidation and torture have come out of the country, as our interview with the wife of an arrested protester reveals. But now almost three weeks on the people are still making their voices heard. Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, Lukashenko’s only opponent during the election after other contenders were picked off, spoke to the European parliament’s foreign affairs committee from Lithuania where she has fled to escape violence: “The intimidation didn’t work. We will not relent.” Could this finally mark the end of Europe’s last dictator? We all hope so. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]