7 Jan 2016 | Campaigns, Europe and Central Asia, France, mobile, Statements

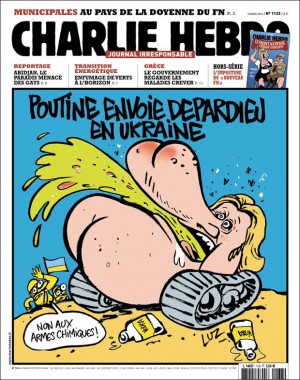

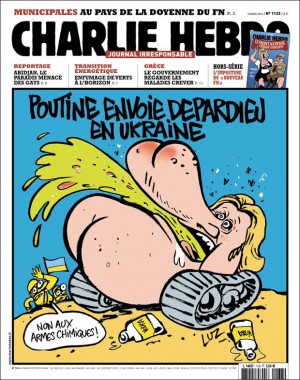

On the anniversary of the brutal attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo we, the undersigned, reaffirm our commitment to the defence of the right to freedom of expression, even when that right is being used to express views that some may consider offensive.

The Charlie Hebdo attack, which left 11 dead and 12 wounded, was a horrific reminder of the violence to which journalists, artists and other critical voices are subjected in a global atmosphere marked by increasing intolerance of dissent. The killings inaugurated a year that has proved especially challenging for proponents of freedom of opinion.

Non-state actors perpetrated violence against their critics largely with impunity, including the brutal murders of four secular bloggers in Bangladesh by Islamist extremists, and the killing of an academic, M M Kalburgi, who wrote critically against Hindu fundamentalism in India.

Despite the turnout of world leaders on the streets of Paris in an unprecedented display of solidarity with free expression following the Charlie Hebdo murders, artists and writers faced intense repression from governments throughout the year. In Malaysia, cartoonist Zunar is facing a possible 43-year prison sentence for alleged ‘sedition’; in Iran, cartoonist Atena Fardaghani is serving a 12-year sentence for a political cartoon; and in Saudi Arabia, Palestinian poet Ashraf Fayadh was sentenced to death for the views he expressed in his poetry.

Perhaps the most far-reaching threats to freedom of expression in 2015 came from governments ostensibly motivated by security concerns. Following the attack on Charlie Hebdo, 11 interior ministers from European Union countries including France, Britain and Germany issued a statement in which they called on Internet service providers to identify and remove online content ‘that aims to incite hatred and terror.’ In July, the French Senate passed a controversial law giving sweeping new powers to the intelligence agencies to spy on citizens, which the UN Human Rights Committee categorised as “excessively broad”.

This kind of governmental response is chilling because a particularly insidious threat to our right to free expression is self-censorship. In order to fully exercise the right to freedom of expression, individuals must be able to communicate without fear of intrusion by the State. Under international law, the right to freedom of expression also protects speech that some may find shocking, offensive or disturbing. Importantly, the right to freedom of expression means that those who feel offended also have the right to challenge others through free debate and open discussion, or through peaceful protest.

On the anniversary of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, we, the undersigned, call on all Governments to:

- Uphold their international obligations to protect the rights of freedom of expression and information for all, and especially for journalists, writers, artists and human rights defenders to publish, write and speak freely;

- Promote a safe and enabling environment for those who exercise their right to freedom of expression, and ensure that journalists, artists and human rights defenders may perform their work without interference;

- Combat impunity for threats and violations aimed at journalists and others exercising their right to freedom of expression, and ensure impartial, timely and thorough investigations that bring the executors and masterminds behind such crimes to justice. Also ensure victims and their families have expedient access to appropriate remedies;

- Repeal legislation which restricts the right to legitimate freedom of expression, especially vague and overbroad national security, sedition, obscenity, blasphemy and criminal defamation laws, and other legislation used to imprison, harass and silence critical voices, including on social media and online;

- Ensure that respect for human rights is at the heart of communication surveillance policy. Laws and legal standards governing communication surveillance must therefore be updated, strengthened and brought under legislative and judicial control. Any interference can only be justified if it is clearly defined by law, pursues a legitimate aim and is strictly necessary to the aim pursued.

PEN International

ActiveWatch – Media Monitoring Agency

Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

Africa Freedom of Information Centre

ARTICLE 19

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Belarusian Association of Journalists

Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism

Bytes for All

Cambodian Center for Human Rights

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Center for Independent Journalism – Romania

Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

Comité por la Libre Expresión – C-Libre

Committee to Protect Journalists

Electronic Frontier Foundation

Foundation for Press Freedom – FLIP

Freedom Forum

Fundamedios – Andean Foundation for Media Observation and Study

Globe International Center

Independent Journalism Center – Moldova

Index on Censorship

Initiative for Freedom of Expression – Turkey

Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information

Instituto de Prensa y Libertad de Expresión – IPLEX

Instituto Prensa y Sociedad de Venezuela

International Federation of Journalists

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions

International Press Institute

International Publishers Association

Journaliste en danger

Maharat Foundation

MARCH

Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance

Media Foundation for West Africa

National Union of Somali Journalists

Observatorio Latinoamericano para la Libertad de Expresión – OLA

Pacific Islands News Association

Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedoms – MADA

PEN American Center

PEN Canada

Reporters Without Borders

South East European Network for Professionalization of Media

Vigilance pour la Démocratie et l’État Civique

World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters – AMARC

PEN Mali

PEN Kenya

PEN Nigeria

PEN South Africa

PEN Eritrea in Exile

PEN Zambia

PEN Afrikaans

PEN Ethiopia

PEN Lebanon

Palestinian PEN

Turkish PEN

PEN Quebec

PEN Colombia

PEN Peru

PEN Bolivia

PEN San Miguel

PEN USA

English PEN

Icelandic PEN

PEN Norway

Portuguese PEN

PEN Bosnia

PEN Croatia

Danish PEN

PEN Netherlands

German PEN

Finnish PEN

Wales PEN Cymru

Slovenian PEN

PEN Suisse Romand

Flanders PEN

PEN Trieste

Russian PEN

PEN Japan

16 Dec 2015 | Awards, Events, mobile, Press Releases

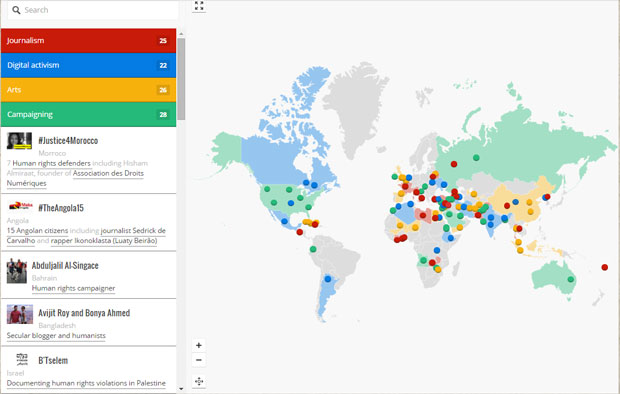

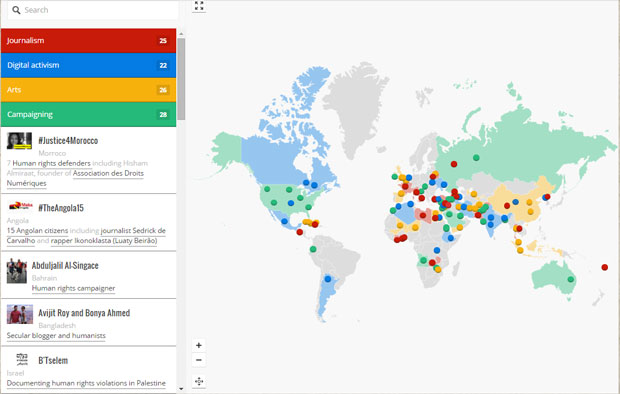

A graffiti artist who paints murals in war-torn Yemen, a jailed Bahraini academic and the Ethiopia’s Zone 9 bloggers are among those honoured in this year’s #Index100 list of global free expression heroes.

Selected from public nominations from around the world, the #Index100 highlights champions against censorship and those who fight for free expression against the odds in the fields of arts, journalism, activism and technology and whose work had a marked impact in 2015.

Those on the long list include Chinese human rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang, Angolan journalist Sedrick de Carvalho, website Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently and refugee arts venue Good Chance Calais. The #Index100 includes nominees from 53 countries ranging from Azerbaijan to China to El Salvador and Zambia, and who were selected from around 500 public nominations.

“The individuals and organisations listed in the #Index100 demonstrate courage, creativity and determination in tackling threats to censorship in every corner of globe. They are a testament to the universal value of free expression. Without their efforts in the face of huge obstacles, often under violent harassment, the world would be a darker place,” Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg said.

Those in the #Index100 form the long list for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards to be presented in April. Now in their 16th year, the awards recognise artists, journalists and campaigners who have had a marked impact in tackling censorship, or in defending free expression, in the past year. Previous winners include Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai, Argentina-born conductor Daniel Barenboim and Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat.

A shortlist will be announced in January 2016 and winners then selected by an international panel of judges. This year’s judges include Nobel Prize winning author Wole Soyinka, classical pianist James Rhodes and award-winning journalist María Teresa Ronderos. Other judges include Bahraini human rights activist Nabeel Rajab, tech “queen of startups” Bindi Karia and human rights lawyer Kirsty Brimelow QC.

The winners will be announced on 13 April at a gala ceremony at London’s Unicorn Theatre.

The awards are distinctive in attempting to identify individuals whose work might be little acknowledged outside their own communities. Judges place particular emphasis on the impact that the awards and the Index fellowship can have on winners in enhancing their security, magnifying the impact of their work or increasing their sustainability. Winners become Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellows and are given support for the year after their fellowship on one aspect of their work.

“The award ceremony was aired by all community radios in northern Kenya and reached many people. I am happy because it will give women courage to stand up for their rights,” said 2015’s winner of the Index campaigning award, Amran Abdundi, a women’s rights activist working on the treacherous border between Somalia and Kenya.

Each member of the long list is shown on an interactive map on the Index website where people can find out more about their work. This is the first time Index has published the long list for the awards.

For more information on the #Index100, please contact [email protected] or call 0207 260 2665.

25 Nov 2015 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns, mobile, Statements

Photographer Sayed Ahmed al-Mousawi

Award-winning photographer Sayed Ahmed al-Mousawi was sentenced on Monday, 23 November 2015, to 10 years in prison and had his nationality revoked, along with 12 others, after covering a series of demonstrations in early 2014. Security forces detained Al-Mousawi for over a year without trial or official charges, accused him of being a part of a terrorist cell and subjected him to torture. The undersigned NGOs condemn the government’s continued attacks on independent journalism, policy of media censorship and severe restrictions on freedom of expression in Bahrain.

Sayed Ahmed al-Mousawi, a winner of 127 international photography awards, has been incarcerated since his arrest on 10 February 2014, when security forces raided his home in Duraz village. According to al-Mousawi’s father, a group of plainclothes masked policemen arrested Sayed Ahmed and his brother. The police provided no arrest warrant and confiscated al-Mousawi’s cameras and electronic devices. Al-Mousawi alleges that he was tortured during his detention and interrogation.

Al-Mousawi’s torture follows a pattern of abuse Human Rights Watch documented in a new report released on 24 November on the ongoing use of torture in Bahraini police detention and prison. Police disappeared and tortured al-Mousawi for five days, subjecting him to severe beatings on his genitals, electrocution and hanging from a door. For the duration of his disappearance, he was stripped naked and forced to stand for long periods of time. Officers did not allow a lawyer to accompany al-Mousawi when they transferred him to the Public Prosecutor. Courts renewed al-Mousawi’s pre-trial detention six times, and he spent over a year in prison without formal charges.

“Sayed al-Mousawi’s torture took place at a time when the UK has been increasing its spending on a ‘reform programme’ for Bahrain to bolster its institutions,” said Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, Director of Advocacy at BIRD. “It is becoming increasingly clear that this programme has failed. Torture is still systematic and unrelenting and the government has broken all promises of reform.”

During his extended detention, al-Mousawi continued to win international awards for his photography. In spite of this, the government accused him of giving SIM cards to “terrorist” demonstrators and taking photos of anti-government protests. As a result, Bahrain tried al-Mousawi under Bahrain’s vague anti-terrorism legislation. A judge later accused him and his brother of membership in a terrorist cell, which al-Mousawi continues to deny.

“Al-Mousawi’s case exposes Bahrain’s continued misapplication of its counterterrorism law to hide evidence of its human rights abuses,” said Husain Abdulla the Executive Director of ADHRB. “Taking photos of peaceful protestors is not a crime and Bahrain’s overreaction shows just how fearful the Bahraini government is of its own people.”

Bahrain’s continued arrest of journalists and photographers, who expose human rights violations, reflects a systematic campaign by the authorities to quell freedom of expression and the press. Bahrain is ranked 163 out of 180 in the 2015 World Press Freedom Index according to Reporters Without Borders. Last year, a Bahraini court also convicted another renowned photojournalist, Ahmed al-Humaidan to 10 years in prison under similar charges. Bahrain has revoked the citizenship of more than 130 individuals since 2012.

“Yet again the Bahraini government has wielded citizenship as a weapon of censorship against journalists,” said CPJ’s Middle East and North Africa program coordinator, Sherif Mansour. “We call on the Bahraini judiciary to overturn this disturbing sentence, recognize al-Mousawi’s citizenship, and free him immediately.”

We, the undersigned NGOs, call for the immediate release of Sayed Ahmed al-Mousawi, and on Bahrain to end the criminalization of free speech and press. We also call on the UK government to suspend its spending on technical assistance to Bahrain, and on the US government to reinstate the ban on arms sales to the country, until systematic torture has been eradicated and restrictions on the enjoyment of internationally-codified human rights are lifted.

Sincerely,

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR)

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Index on Censorship

24 Nov 2015

Since 1972, our work has given a voice to those who face imprisonment, torture and even death for speaking out.

Your money helps us support individuals like Mouad Belghouat, a Moroccan rapper, whose concerts have been repeatedly shut down by authorities over his criticism of corruption. Or Rafael Marques de Morais, who faces the constant threat of jail because of his investigations into Angola’s blood diamonds industry. Or Maryam al-Khawaja, a Bahraini activist for whose release from jail Index successfully campaigned. Or Dina Meza, who lives under constant fear and threats because of her work as an investigative journalist in Honduras.

Index works tirelessly, exposing these stories online, in our magazine and in the press; supporting the individuals who battle censorship and advocating for free speech in the UK.

“I could not look into my children’s eyes and tell them I can do nothing about the situation, because to do nothing would be far worse than the threats, beatings or bullets of the police and the military.”

Dina Meza

Be One

Free speech is not free. We rely on the generous support of donors and supporters to enable our work. By giving over £5,000 a year and joining Index Advocates you will receive:

• Recognition in our quarterly magazine and annual report

• Annual subscription to our magazine

• Invitations to all of Index’s cutting edge events

• Tickets to Index’s keynote event, the annual Freedom of Expression Awards

• Tickets to our new annual event, the Free Expression Award Winners’ Dinner.

If you would be interested in learning more about becoming an Index Advocate please contact Helen Galliano:

[email protected] or 0207 260 2660

If you are a US donor and would like more information about tax deductible charitable giving to Index, please contact [email protected]. Index works with CAF American Donor Fund.

“I have been privileged to be associated with Index on Censorship for some years, during which time I have been humbled over and over again by meeting the sort of people for whom Index on Censorship is an absolute lifeline – people who risk their lives and liberty daily to tell the truth.”

Simon Callow, Index Patron