4 Feb 2014 | Digital Freedom, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Today Facebook celebrates its 10th anniversary. The social networking giant now has over 1.23 billion users, but there are still political leaders around the world who don’t want their country to have access to the site, or those who have banned it in the past amid fears it could be used to organise political rallies.

North Korea

Perhaps the most secretive country in the world little is known about internet access in Kim Jong-un’s nation. Although a new 3G network is available to foreign visitors, for the majority of the population the internet is off limits. But this doesn’t seem to bother many who, not knowing any different, enjoy the limited freedoms offered to them by the country’s intranet, Kwangmyong, which appears to be mostly used to post birthday messages.

A limited number of graduate students and professors at Pyongyang University of Science and Technology do have access to the internet (from a specialist lab) but in fear of the outside world many chose not to use it. Don’t expect to see Kim Jong-un’s personal Facebook page any time soon.

Iran

In Iran, however, political leaders have taken to social media- despite both Facebook and Twitter officially being extraordinarily difficult to access in the country. Even President Hassan Rouhani has his own Twitter account, although apparently he doesn’t write his own tweets, but access to these accounts can only be gained via a proxy server.

Facebook was initially banned in the country after the 2009 election amid fears that opposition movements were being organised via the website.

But things may be beginning to looking up as Iran’s Culture Minister, Ali Jannati, recently remarked that social networks should be made accessible to ordinary Iranians.

China

The Great Firewall of China, a censorship and surveillance project run by the Chinese government, is a force to be reckoned with. And behind this wall sits the likes of Facebook.

The social media site was first blocked following the July 2009 Ürümqi riots after it was perceived that Xinjiang activists were using Facebook to communicate, plot and plan. Since then, China’s ruling Communist Party has aggressively controlled the internet, regularly deleting posts and blocking access to websites it simply does not like the look of.

Technically, the ban on Facebook was lifted in September 2013. But only within a 17-square-mile free-trade zone in Shanghai and only to make foreign investors feel more at home. For the rest of China it is a waiting game to see if the ban lifts elsewhere.

Cuba

Facebook isn’t officially banned in Cuba but it sure is difficult to access it.

Only politicians, some journalists and medical students can legally access the web from their homes. For everyone else the only way to connect to the online world legally is via internet cafes. This may not seem much to ask but when rates for an hour of unlimited access to the web cost between $6 and $10 and the average salary is around $20 getting online becomes ridiculously expensive. High costs also don’t equal fast internet as web pages can take several minutes to load: definitely not value for money for the Caribbean country.

Bangladesh

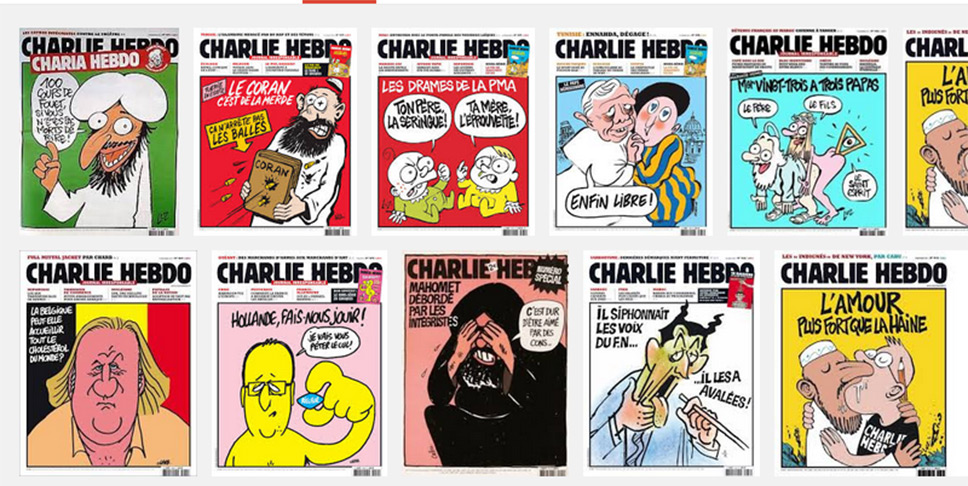

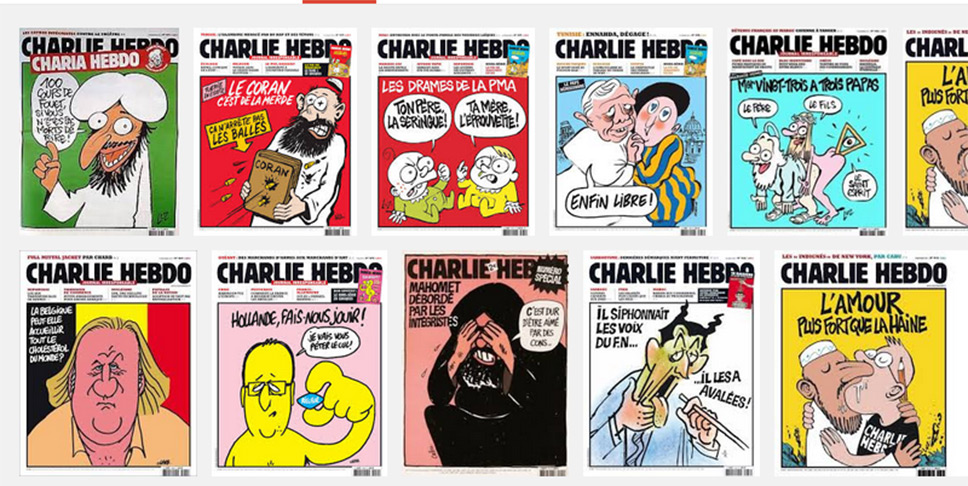

The posting of a cartoon to Facebook saw the networking site shut down across Bangladesh in 2010. Satirical images of the prophet Muhammad, along with some of the country’s leaders, saw one man arrested and charged with “spreading malice and insulting the country’s leaders”. The ban lasted for an entire week while the images were removed.

Since then the Awami-League led government has directed a surveillance campaign at Facebook, and other social networking sites, looking for blasphemous posts.

Article continues below[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Stay up to date on freedom of expression” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that defends people’s freedom to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution. We fight censorship around the world.

To find out more about Index on Censorship and our work protecting free expression, join our mailing list to receive our weekly newsletter, monthly events email and periodic updates about our projects and campaigns. See a sample of what you can expect here.

Index on Censorship will not share, sell or transfer your personal information with third parties. You may may unsubscribe at any time. To learn more about how we process your personal information, read our privacy policy.

You will receive an email asking you to confirm your subscription to the weekly newsletter, monthly events roundup and periodic updates about our projects and campaigns.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Egypt

As Egyptians took to the streets in 2011 in an attempt to overthrow the regime of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak the government cut off access to a range of social media sites. As well as preventing protestors from using the likes of Facebook to foment unrest, many websites registered in Egypt could no longer be accessed by the outside world. Twitter, YouTube, Hotmail, Google, and a “proxy service” – which would have allowed Egyptians to get around the enforced restrictions- seemed to be blocked from inside the country.

The ban lasted for several days.

Syria

Syria, however, dealt with the Arab Spring in a different manner. Facebook had been blocked in the country since 2007 as part of a crackdown on political activism, as the government feared Israeli infiltration of Syrian social networking sites. In an unprecedented move in 2011 President Bashar al-Assad lifted the five year ban in an apparent attempt to prevent unrest on his own soil following the discontent in Egypt and Tunisia.

During the ban Syrians were still able to easily access Facebook and other social networking sites using proxy servers.

Mauritius

Producing fake online profiles of celebrities is something of a hobby to some people. However, when a Facebook page proclaiming to be that of Mauritius Prime Minister Navin Ramgoolam was discovered by the government in 2007 the entire Mauritius Facebook community was plunged into darkness. But the ban didn’t last for long as full access to the site was restored the following day.

These days it would seem Dr Ramgoolam has his own (real) Facebook account.

Pakistan

Another case of posting cartoons online, another case of a government banning Facebook. This time Pakistan blocked access to the website in 2010 after a Facebook page, created to promote a global online competition to submit drawings of the prophet Muhammad, was brought to their attention. Any depiction of the prophet is proscribed under certain interpretations of Islam.

The ban was lifted two weeks later but Pakistan vowed to continue blocking individual pages that seemed to contain blasphemous content.

Vietnam

During a week in November 2009, Vietnamese Facebook users reported an inability to access the website following weeks of intermittent access. Reports suggested technicians had been ordered by the government to block the social networking site, with a supposedly official decree leaked on the internet (although is authenticity was never confirmed). The government denied deliberately blocking Facebook although access to the site today is still hit-and-miss in the country.

Alongside this, what can be said on social networking sites like Facebook has also become limited. Decree 72, which came into place in September 2013, prohibits users from posting links to news stories or other news related websites on the social media site.

This article was published on 4 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1538131415482-d092e45b-9f66-5″ taxonomies=”136″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, Index Reports, News, Politics and Society

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

Beyond its near neighbourhood, the EU works to promote freedom of expression in the wider world. To promote freedom of expression and other human rights, the EU has 30 ongoing human rights dialogues with supranational bodies, but also large economic powers such as China.

The EU and freedom of expression in China

The focus of the EU’s relationship with China has been primarily on economic development and trade cooperation. Within China some commentators believe that the tough public noises made by the institutions of the EU to the Chinese government raising concerns over human rights violations are a cynical ploy so that EU nations can continue to put financial interests first as they invest and develop trade with the country. It is certainly the case that the member states place different levels of importance on human rights in their bilateral relationships with China than they do in their relations with Italy, Portugal, Romania and Latvia. With China, member states are often slow to push the importance of human rights in their dialogue with the country. The institutions of the European Union, on the other hand, have formalised a human rights dialogue with China, albeit with little in the way of tangible results.

The EU has a Strategic Partnership with China. This partnership includes a political dialogue on human rights and freedom of the media on a reciprocal basis.[1] It is difficult to see how effective this dialogue is and whether in its present form it should continue. The EU-China human rights dialogue, now 14 years old, has delivered no tangible results.The EU-China Country Strategic Paper (CSP) 2007-2013 on the European Commission’s strategy, budget and priorities for spending aid in China only refers broadly to “human rights”. Neither human rights nor access to freedom of expression are EU priorities in the latest Multiannual Indicative Programme and no money is allocated to programmes to promote freedom of expression in China. The CSP also contains concerning statements such as the following:

“Despite these restrictions [to human rights], most people in China now enjoy greater freedom than at any other time in the past century, and their opportunities in society have increased in many ways.”[2]

Even though the dialogues have not been effective, the institutions of the EU have become more vocal on human rights violations in China in recent years. For instance, it included human rights defenders, including Ai Weiwei, at the EU Nobel Prize event in Beijing. The Chinese foreign ministry responded by throwing an early New Year’s banquet the same evening to reduce the number of attendees to the EU event. When Ai Weiwei was arrested in 2011, the High Representative for Foreign Affairs Catherine Ashton issued a statement in which she expressed her concerns at the deterioration of the human rights situation in China and called for the unconditional release of all political prisoners detained for exercising their right to freedom of expression.[3] The European Parliament has also recently been vocal in supporting human rights in China. In December 2012, it adopted a resolution in which MEPs denounced the repression of “the exercise of the rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly, press freedom and the right to join a trade union” in China. They criticised new laws that facilitate “the control and censorship of the internet by Chinese authorities”, concluding that “there is therefore no longer any real limit on censorship or persecution”. Broadly, within human rights groups there are concerns that the situation regarding human rights in China is less on the agenda at international bodies such as the Human Rights Council[4] than it should be for a country with nearly 20% of the world’s population, feeding a perception that China seems “untouchable”. In a report on China and the International Human Rights System, Chatham House quotes a senior European diplomat in Geneva, who argues “no one would dare” table a resolution on China at the HRC with another diplomat, adding the Chinese government has “managed to dissuade states from action – now people don’t even raise it”. A small number of diplomats have expressed the view that more should be done to increase the focus on China in the Council, especially given the perceived ineffectiveness of the bilateral human rights dialogues. While EU member states have shied away from direct condemnation of China, they have raised freedom of expression abuses during HRC General Debates.

The Common Foreign and Security Policy and human rights dialogues

The EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) is the agreed foreign policy of the European Union. The Maastricht Treaty of 1993 allowed the EU to develop this policy, which is mandated through Article 21 of the Treaty of the European Union to protect the security of the EU, promote peace, international security and co-operation and to consolidate democracy, the rule of law and respect for human rights and fundamental freedom. Unlike most EU policies, the CFSP is subject to unanimous consensus, with majority voting only applying to the implementation of policies already agreed by all member states. As member states still value their own independent foreign policies, the CFSP remains relatively weak, and so a policy that effectively and unanimously protects and promotes rights is at best still a work in progress. The policies that are agreed as part of the Common Foreign and Security Policy therefore be useful in protecting and defending human rights if implemented with support. There are two key parts of the CFSP strategy to promote freedom of expression, the External Action Service guidelines on freedom of expression and the human rights dialogues. The latter has been of variable effectiveness, and so civil society has higher hopes for the effectiveness of the former.

The External Action Service freedom of expression guidelines

As part of its 2012 Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy, the EU is working on new guidelines for online and offline freedom of expression, due by the end of 2013. These guidelines could provide the basis for more active external policies and perhaps encourage a more strategic approach to the promotion of human rights in light of the criticism made of the human rights dialogues.

The guidelines will be of particular use when the EU makes human rights impact assessments of third countries and in determining conditionality on trade and aid with non-EU states. A draft of the guidelines has been published, but as these guidelines will be a Common Foreign and Security Policy document, there will be no full and open consultation for civil society to comment on the draft. This is unfortunate and somewhat ironic given the guidelines’ focus on free expression. The Council should open this process to wider debate and discussion.

The draft guidelines place too much emphasis on the rights of the media and not enough emphasis on the role of ordinary citizens and their ability to exercise the right to free speech. It is important the guidelines deal with a number of pressing international threats to freedom of expression, including state surveillance, the impact of criminal defamation, restrictions on the registration of associations and public protest and impunity against human right defenders. Although externally facing, the freedom of expression guidelines may also be useful in indirectly establishing benchmarks for internal EU policies. It would clearly undermine the impact of the guidelines on third parties if the domestic policies of EU member states contradict the EU’s external guidelines.

Human rights dialogues

Another one of the key processes for the EU to raise concerns over states’ infringement of the right to freedom of expression as part of the CFSP are the human rights dialogues. The guidelines on the dialogues make explicit reference to the promotion of freedom of expression. The EU runs 30 human rights dialogues across the globe, with the key dialogues taking place in China (as above), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Georgia and Belarus. It also has a dialogues with the African Union, all enlargement candidate countries (Croatia, the former Yugoslav republic of Macedonia and Turkey), as well as consultations with Canada, Japan, New Zealand, the United States and Russia. The dialogue with Iran was suspended in 2006. Beyond this, there are also “local dialogues” at a lower level, with the Heads of EU missions, with Cambodia, Bangladesh, Egypt, India, Israel, Jordan, Laos, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, the Palestinian Authority, Sri Lanka, Tunisia and Vietnam. In November 2008, the Council decided to initiate and enhance the EU human rights dialogues with a number of Latin American countries.

It is argued that because too many of the dialogues are held behind closed doors, with little civil society participation with only low-level EU officials, it has allowed the dialogues to lose their importance as a tool. Others contend that the dialogues allow the leaders of EU member states and Commissioners to silo human rights solely into the dialogues, giving them the opportunity to engage with authoritarian regimes on trade without raising specific human rights objections.

While in China and Central Asia the EU’s human rights dialogues have had little impact, elsewhere the dialogues are more welcome. The EU and Brazil established a Strategic Partnership in 2007. Within this framework, a Joint Action Plan (JAP) covering the period 2012-2014 was endorsed by the EU and Brazil, in which they both committed to “promoting human rights and democracy and upholding international justice”. To this end, Brazil and the EU hold regular human rights consultations that assess the main challenges concerning respect for human rights, democratic principles and the rule of law; advance human rights and democracy policy priorities and identify and coordinate policy positions on relevant issues in international fora. While at present, freedom of expression has not been prioritised as a key human rights challenge in this dialogue, the dialogues are seen by both partners as of mutual benefit. It is notable that in the EU-Brazil dialogue both partners come to the dialogues with different human rights concerns, but as democracies. With criticism of the effectiveness and openness of the dialogues, the EU should look again at how the dialogues fit into the overall strategy of the Union and its member states in the promotion of human rights with third countries and assess whether the dialogues can be improved.

[1] It covers both press freedom for the Chinese media in Europe and also press freedom for European media in China.

[2] China Strategy Paper 2007-2013, Annexes, ‘the political situation’, p. 11

[3] “I urge China to release all of those who have been detained for exercising their universally recognised right to freedom of expression.”

[4] Interview with European diplomat, February 2013.

23 Dec 2013 | Volume 42.04 Winter 2013

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is and article by Samira Ahmed on how 15 years of multiculturalism and how some people’s ideas of it are getting in the way of freedom of expression from the winter 2013 issue. This article is a great starting point for those planning to attend the Faith and education: an uneasy partnership session at the festival.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

In 1999, the neo-Nazi militant David Copeland planted three nail bombs in London – in Brixton, Brick Lane and Soho – targeting black people, Bangladeshi Muslims and gays and lesbians. Three people died and scores were injured.

In response, the government awarded funds to local charities and community groups working on projects to build cohesion among the people that had been the targets of Copeland’s bloody campaign.

The intention was honorable, the impact underwhelming. According to Angela Mason, then head of Stonewall, the gay rights pressure group, the assumption was that all the people targeted by Copeland were “on the same side”. The truth as she sees it was that the government-funded projects exposed the uncomfortable reality that there were strong anti-gay prejudices among Muslim, Christian and black communities in Britain.

How realistic is it to expect a cohesive society could emerge from this kind of climate?

Today, the tensions between freedom of speech and religious belief remain acute – and they are systematically exploited by political groups of all stripes, from the English Defence League to radical Islamists who threaten to disrupt the repatriation of dead British soldiers at Wootton Bassett. The story consistently makes the headlines. The idea that there is an Islamist assault on British freedoms and values is widespread.

The Muslim campaign against Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses in 1988 was the crucial moment in all this. It forced writers and artists from an Asian or Muslim background, whether they defined themselves that way or not, to take sides. They had to declare loyalty – or otherwise – to the offended.

The results have been appalling, and not only in Britain. Most notoriously, the Somali writer and Dutch politician Ayaan Hirsi Ali had her citizenship withdrawn by the Dutch authorities just as Muslim expressions of outrage and death threats in response to her writing about Islam reached their peak.

In the UK, local authorities have been all too ready to cave in to pressure under cover of preventing community unrest, maintaining public order or resisting perceived cultural insensitivity.

Sensitivity to religious insult, too often conflated with racism, has frequently taken precedence over concern for free expression. In 2004 violent protests by Birmingham Sikhs led to the closure of Behzti, Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s play on rape and abuse of women in a Sikh temple.

But the problem is not always obvious. In September 2012, Jasvinder Sanghera, founder of Karma Nirvana, a charity campaigning against forced marriage, ran a stall at the National Union of Teachers conference, distributing posters for schools. She told the Rationalist Association: “Many teachers came to my stall and many said, ‘Well, we couldn’t put them up. It’s cultural, we wouldn’t want to offend communities and we wouldn’t get support from the headteacher.’ And that was the majority view of over 100 teachers who came to speak to me.”

Sanghera said that one teacher who did take a poster sent her photographs of it displayed on a noticeboard in his school. But “within 24 hours of him putting up the posters, the headteacher tore them all down”. The teacher was summoned to the head’s office and told: “Under no circumstances must you ever display those posters again because we don’t want to upset our Muslim parents.”

The delayed prosecution of predominantly Asian Muslim grooming gangs in Rochdale and Oxford has to be seen in the context of the long-standing local authority fear of causing offence. Women’s rights, artistic free speech, even child protection have repeatedly been downgraded in order to avoid the accusation of racism or religious insult.

It’s not as bad as it used to be, according to Peter Tatchell, whose organisation OutRage! promotes the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people and has campaigned against homophobic and misogynist comments by Islamic preachers and organisations. “Official attitudes are better in terms of defending free speech but still far from perfect,” he says. However, he adds, “Police and prosecutors still sometimes take the view that causing offence is sufficient grounds for criminal action, especially where religious and racial sensitivities are involved.”

The pressure isn’t necessarily overt but individual writers say they are struggling to work out where the lines are being drawn.

Writer Yasmeen Khan’s work ranges from making factual programmes, including documentaries for BBC Radio Four, to writing and performing comedy and drama. She says: “The pressure not to ‘offend’ has certainly increased over the past few years,” though she adds that it has probably affected writers and performers outside a particular religion more than believers.

Being seen as a religious believer can be an advantage when it comes to commissioning or applying for grants, she says. “But the downside is that you’re sometimes only viewed through that lens; you don’t want to be seen as a ‘Muslim writer’ – you just want to be a writer. It can feel like you’re being pigeon-holed by others, and that holds you back as being seen as ‘mainstream’. I’ve seen that issue itself being used for comedy – I was part of an Edinburgh show for which we wrote a sketch about an Asian writer being asked to ‘Muslim-up’ her writing.”

Luqman Ali runs the award-winning Khayaal Theatre company in Luton. It has built a strong critical reputation for its dramatic interpretation of classical Islamic literature. He dismisses the assertion that political correctness has shut down artistic freedom: “There would appear to be an entrenched institutional narrative that casts Muslims as problem people and Muslim artists as worthy only in so far as they are either prepared to lend credence to this narrativeor are self-avowedly irreligious,” he says. He contrasts what he sees as the “retrospective acceptance” of historic Islamic art and literary texts in museum collections with “very little acceptance of contemporary Muslim cultural production, especially in the performing arts”.

In 2011, the TLC channel in the US cancelled the reality TV series All American Muslim, a programme about a family in Michigan, after only one season. The cancellation followed a campaign by the Florida Family Association that was reminiscent of the UK group Christian Voice’s campaign against Jerry Springer: The Opera in 2005. Lowe’s, a national home-improvement chainstore and major advertiser, pulled out of sponsoring the show after the group claimed the series was “propaganda that riskily hides the Islamic agenda’s clear and present danger to American liberties and traditional values”.

Lowe’s denied its decision was in response to the Florida Family Association campaign. But amid the hysteria generated, including protests outside Lowe’s stores, ratings for the show plummeted. Many Americans decided not to watch it. As with Jerry Springer: The Opera, a small group had created a momentum of outrage that led to a fatal atmosphere of threat and intimidation around a piece of mainstream – and until then, highly successful – entertainment. The Bollywood thriller Madras Café was withdrawn from Cineworld and Odeon cinemas in the UK and Tamil Nadu, India, after a campaign by Tamil groups who found it “offensive”.

Veteran comedy writer John Lloyd, speaking at a British Film Institute event marking the 50th anniversary of the broadcast of the satirical news programme That Was The Week That Was in 2012, said there was now an obsession with “compliance” by tier after tier of broadcast managers, which he felt had suffocated satire. “Now,” said Lloyd, “everyone’s jibbering in fright if you do anything at all.” He contrasted the current climate to his experience working for Not The Nine O’ Clock News when, he said, he was “encouraged to provoke and challenge”.

Writer and stand-up comedian Stewart Lee, who co-wrote Jerry Springer: The Opera, is currently working on a new series of his award-winning Comedy Vehicle for BBC Two. He believes a general uncertainty about British legislation on religious offence is affecting what gets produced: “It’s all very confusing. I don’t know what I am allowed to say. There is a culture of fear generally now in broadcasting. No one knows what they are allowed to do.”

“In Edinburgh in August 2013, a (nonbroadcast) show in a tent funded by the BBC at 9.30pm saw the BBC person running it pull a song by the gay musical comedy duo Jonny and the Baptists about laws concerning gays giving blood because it ‘promoted homosexuality’. This at 9.30pm, in a country where it is not illegal to promote homosexuality, and not for broadcast.

“In series one of Comedy Vehicle, I had a bit on imagining Islamists training dogs to fly planes into buildings. This was pulled on the grounds that it appeared deliberately provocative to Muslims because of the dog taboo in Islam. I looked into this, and read a load of stuff on it. There is no dog taboo in the Muslim faith.”

A BBC spokesman said: “The band were invited to perform on our open garden stage which was run as a family friendly venue for the 24 days it was open to the public. With the possibility of children and young people in the audience, we asked the band to tailor their short set to reflect the audience. They did so, and in one of these, a late night notfor- broadcast show, their set included the song which Stewart Lee refers to. The BBC has a strong track record of offering comedians opportunities to perform their edgiest material without restraint during the festival and we will continue to do so.”

Lee described the Jerry Springer: The Opera debacle, explaining that the pressure group Christian Voice “were able to scupper the viability of the 2005-2006 tour” of the play by informing theatres they would be prosecuted under the forthcoming incitement to religious hatred bill if they staged the play. The bill was later defeated by one vote in the Commons, and soon after the House of Lords scrapped the blasphemy laws. “But,” says Lee, “I think the public perception is that both these laws still exist.”

He says he doesn’t like to make a fuss: “The BBC is beset on all sides by politically and economically interested partners who want to see it destroyed. I wouldn’t expect the BBC, any more, to go to the wall about something I wanted to say. I’d just say it somewhere else – on a long touring show for example – and get better paid for it anyway! I am also anxious not to appear to contribute to the notion that ‘political correctness has gone mad’. People say, ‘ah but you’ve never done stuff about Islam’. I have. Nothing happened. But I have not done stuff about Islam in the depth I have stuff about Christianity as it is not relevant to me in the same way.”

Lee says his writing for tours isn’t affected by the fear of offence because his solo tours are “cost-effective and largely off the radar of the anti-PC brigade or people looking for things to complain about”.

However, he says, when it comes to the television series, he does consider the power of offence. “It affects what I write,” he says. His new show addresses the Football Association’s objection to the word “nigger”. He suspects that the BBC might get cold feet about this bit. “So I will drop it and use it live and on DVD. I don’t see TV as the place to experiment with certain types of content any more.”

But he says that one of the most important things about freedom of speech is that it applies to everyone. “I don’t think a lot of the jokes that, say, Jimmy Carr and Frankie Boyle do are worth the annoyance they cause, but I would defend their right to say them.”

So what, if anything, has changed for writers and what they feel they can write about since his experience with Jerry Springer?

“It’s all much worse,” Lee says. “But for many reasons: lack of funding mainly.” In April 2013, culture secretary Maria Miller addressed members of the arts industry at the British Museum, arguing that: “When times are tough and money is tight, our focus must be on culture’s economic impact.”

But as Lee points out, “it’s harder to justify funding something worthwhile in the current climate if people are storming the publicly funded theatre, such as Behzti, in protest.” “It has lost its moral authority in many ways,” he says, adding that ratings are at the forefront of commissioners’ minds.

There have been high-profile attempts to link comedy and Islam, such as the recent Allah Made Me Funny international standup tours. The Canadian CBC sitcom Little Mosque on the Prairie defied self-styled Muslim community leaders’ complaints about insult and offence to run for six highly-rated seasons, finishing in 2012. The BBC’s own Citizen Khan, which begins its second series in 2014, has similarly ignored claims of insult. Both sitcoms combine a Muslim family setting with very familiar sitcom themes.

In Britain, the overly cautious attitude to free speech and religion supposed to create community harmony has coincided with growing fundamentalist intimidation often promoted within enclosed immigrant communities. Sikh gangs have targeted mixed weddings in temples, and there have been tense stand-offs between Sikhs and Muslims over allegations of sexual grooming in Luton and elsewhere. British Ahmadiyya Muslims, who fled persecution in Pakistan, have struggled to draw media attention to the orchestrated hate campaigns being conducted against them by some Sunni groups. We need to feel free to criticise religious groups when they cross lines and commit crimes, without worrying about the cultural upset.

As Kenan Malik has said, the refusal to confront these issues in open and frank discussion, is “transforming the landscape” of free speech. Even in the United States, where free speech is enshrined in the constitution, there are serious questions being asked about what free speech actually means – particularly when it comes to religion.

The right to free speech should never be half-hearted. People have the right to be offended, but they don’t have the right to stop others speaking, discussing and debating ideas.

18 Oct 2013 | About Index, Events, Volume 42.03 Autumn 2013

The following speech by Sarah Brown, education campaigner for A World at School, was delivered at the launch event for the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

I am delighted to be at Lilian Baylis Technology School – I went to school in North London, but my first flat was just down the road from here – I know how hard everyone at this school has worked for it become the first in Lambeth to get an outstanding in its Ofsted and now stands out as ‘outstanding in all aspects’ in the top 10% in the country. Being named for a pioneering woman who nurtured some amazing talent in the theatre, opera and ballet worlds leaving her mark across London gives the school a lot to live up to, but clearly nurturing some amazing talent here of its own these days.

Index on Censorship’s magazine that we are launching here tonight also serves to highlight some talented voices, and some very courageous ones too. Like all of the magazine editions which came before it, it is distinguished by both the quality of its writing and the bravery of its stance. But this one is particularly important to me for the priority it has placed on the voices of women. From pioneering feminists writing about women’s safety in India to the stories of female resistance and of hope from the Arab Spring, this magazine is giving a megaphone to the people whose contribution is so often marginalised, ignored, or eliminated altogether.

In the spirit of Index on Censorship’s core values, the power of our voice is the theme of my remarks tonight. And I want to start by updating a feminist slogan that lots of women who have done pioneering work on role models have been using for years now. Their view is ‘if she can see it, she can be it’. In other words, if you have a visible role model you are much more likely to keep fighting to get past all of the hurdles that are still too often put in the way of girls and women, just as they are for people who are disabled, or LGBT or BAME, or hold a forbidden political viewpoint in the harshest of regimes around the world.

‘If you can see it, you can be it’ – I very much think that’s true – the importance of strong visible women role models. Even my own sense of what is possible for me has certainly been determined by watching women – whether my own mother learning and leading throughout her life, from running an infant’s school in the 70’s in the middle of Africa, completing her PhD a few years go in her seventies and even now I am struggling to keep up her as she launches a new project leading the research on a study of quilt-makers (mostly women) and the stories they tell. Other role models from me have ranged from the icons of my teenage years from poet and rock artist Patti Smith to writer Jill Tweedie to American feminist Gloria Steinum. Today my work leads me to meet such a range of inspirational women leaders from Graca Machel to Aung San Suu KyI to President Joyce Banda of MalawI to young women like AshwinI Angadi, born blind in a poor rural community in India she fought for her education, graduated from Bangalore university with outstanding grades, gave up her job in IT to campaign for the rights of people with disabilities, and I find myself alongside at the UN last month.

So I agree that visibility counts, but if I think of my role models they are all women who never give up raising their voices – who make a career literally of speaking up. And I want to update that old slogan with a rather more disturbing thought and suggest tonight that if you can hear her, you will fear her.

Let me explain what I mean.

From Nigeria to Egypt to Yemen and Afghanistan to the richest countries of the West, we are seeing the rise of targeted attacks focused on women who use their voice to speak out for other women. Sometimes these attacks are physical, and I will talk about them more in a moment. But here in the UK there has been a spate of attacks which are verbal and online, and which are perpetrated by men who fear women’s power.

From the disgusting rape threats directed at Caroline Criado-Perez for daring to suggest a woman should remain on British bank notes to the horrendous and sexualised verbal violence meted out to Mary Beard after she appeared on question time to model Katie Piper finding her online voice speaking up for the stigma of disfiguration in a defiant response to the acid attack on her, and the creation of her defiant new beauty at the hands of her NHS surgeon. And of course, the all too prevalent victims of domestic violence who get a collective voice through women’s aid and the main refuges around the UK – who speak up more when they see it can even happen to a goddess like Nigella.

It is clear that the public square – and too often the private home – simply doesn’t provide a safe environment for Britain’s women.

If anybody doubts how bad things have got, I’d encourage you to go and take a look at Laura Bates’ work with the Everyday Sexism Project, an online directory of harassment, discrimination and abuse submitted by over 50,000 women who are shouting back. It paints a picture of a Britain in which violence and the threat of violence against women is so routine, women had almost ceased to notice it as a crime and an outrage, until a platform came along that gave their problem visibility and, with it, importance.

So I want to suggest that a public square which is so hostile to women that they do not feel they can participate in it without inviting overwhelming abuse is, itself, a form of censorship. It might not be the same process as smashing up a newspaper office or burning a book or even shooting teenage girls on a school bus, but the effect is the same: that of silencing a voice which has a right to be heard.

And if you want further evidence of how hearing how women’s voices can terrify those who risk losing their power, just consider how the worst misogynists in the world were afraid of just three words.

The words I’m talking about weren’t said by somebody famous. They weren’t said by somebody powerful. They hadn’t even been planned before they were uttered. But they awoke the world.

Malala YousafzaI as a schoolgirl from rural Pakistan published her youthful diary detailing how life had changed for girls after the Taliban took over her mountain town. She and her friends Shazia and Kainat spent the next few years campaigning for girls to be allowed to return to school, although they knew how dangerous speaking out against the Taliban could be. Malala even talked in interviews about how they might try to kill her for it.

Just over a year ago, this worst imagining happened and Malala was targeted by a Taliban assassin. He boarded the school bus, identified Malala and shot her in the head, and injured Shazia and Kainat sitting either side of her. As the footage of Malala’s airlift to safety was broadcast young women used just three words to claim their solidarity and support with her “I am Malala’. She and her two friends are all now safely in the UK continuing their education, and as the worlds’ gaze has given them some safety the campaign continues with a growing movement of young people all of whom are role models for every child around the world, whether in school or waiting for the dream to come true and the opportunity to learn coming to them too.

It was such a powerful reminder of a question I first asked myself some time ago:

Why is the most terrifying thing for the Taliban a girl with a book? Or for that matter the terrifying group in Nigeria – Boko Haram – who are firebombing schools and dormitories while students sleep. Boko Haram – the name literally means – western education is evil.

These terrorists know, better than we do, that a girl with an education is the most formidable force for freedom in the world. A girl who can read and write and argue can be brutalised and oppressed, she can be bought and sold, discriminated against and denied her rights. But she cannot, in the end, be stopped.

Girls like Malala, Kainat, Shazia and others in the end, will prevail.

And that is why they hate them so.

And so it seems to me if a girl like Malala, on her own, can inspire so much fear, then imagine what she could do if backed by a movement of hundreds of millions. That is why I believe that the efforts to achieve global education are at the heart of how we unlock the potential of every young citizen. As children learn, they achieve understanding, tolerance, opportunity and the chance to contribute to a better world. Reaching girls is at the heart of this – we need to do so much better for girls.

Right now, there are 57 million children missing from school. That’s 57 million of our younger selves missing out on the education which could transform not just their lives, but the world. 31 million are girls, and of those at school, many many millions are not learning, and girls are just not getting the same number of school years as their own brothers – to the detriment of everyone.

New research has shown that providing universal education in developing countries could lift their economic growth rates by up to 2% a year and the results are starkest of all when it comes to educating girls.

All the evidence shows that for every extra year of education you give a girl, you raise her children’s chances of living past five years old, because educated mums are more likely to immunise their kids and get them the health care they need. Educated girls are more likely to stay AIDS-free and are less vulnerable to sexual exploitation by adults. They marry later, have fewer children and are more likely to educate their children in turn. Perhaps most importantly of all, education increases a girl’s chance of well-paid employment in later life and the evidence suggests that female earners are more likely to spend their wages to the benefit of their children and community than traditional male heads of the household.

And the benefits, of course, don’t always stay just on a local community level, but can sometimes have national and even global implications too. Because if you look at women who have been in leading positions in every continent around the world – from Sonia GandhI to Graca Machel to Dilma Rousseff to Joyce Banda, they all have one thing in common. They all have an above average level of education. And that’s why one of my new mantras is women who lead, read.

If we want better politics, a politics of pluralism and freedom of expression around the world, then it begins with empowering women – and that begins with educating them.

So there are plenty of good reasons to invest in education and learning for every child – but the best bit is that we’ve already promised to. We are not advocating for a new pledge, simply for the fulfilment of one already made. In the year 2000 world leaders committed to getting every child in school by 2015 as part of a series of ambitious targets called the millennium development goals. World leaders have already signed the contract, now they just need to deliver the goods.

So for me the argument about whether we should invest in education to get the 57 children missing from school into the classroom is a bit of a no brainer – and for me there is no question that closing the gender gap in education should be the priority. As soon as people hear the facts, they tend to stop asking whether we should do it and start to focus on whether we can.

That’s a fair question and people will always want to probe whether we can make a difference to decisions taken hundreds of thousands of miles away. It’s a question I ask myself a lot too. But I take heart from two things. Firstly, we know that progress is possible even on seemingly very big problems because we have made it before. You can look at the big changes in the last century or so – from the end of slavery, achieving the vote for women, the end of apartheid – all started as impossible calls for change, but change came. Enough voices gathered together calling for the same thing – even a politician can’t fail to hear the call then, or if minded to change anyway can do so with a strong mandate behind him or her. Even campaigns I have contributed- that we may all have contribute to – from drop the debt to make poverty history to the maternal mortality campaign brought big changes – but I have heard first-hand what happens at the start – “it is too big an ask, it can’t be done in the time, it is too costly” – well enough free voices calling for action and – give it a little bit of time and a whole lot of noise – change comes. Less than ten years ago over 500,000 women were dying in pregnancy and childbirth unwitnessed, unacknowledged unnoticed by political leaders who held the power to save these lives. Today thanks to the collective voices of those who cared enough – through the white ribbon alliance and others, that number is a whopping 47% lower, and the work to reduce it further continues at the highest levels, and out in the more remote rural areas where the message needs to be carried far and wide to reach every woman at risk.

A 47% drop in the number of mothers dying. That’s not just a number – that means there are thousands of dads living with the love of their lives when they would otherwise have a broken heart nobody else could possibly mend. Thousands of big brothers and sisters who didn’t need to fear that in gaining a new member of the family they risked losing an old one. And thousands of babies being nursed to sleep tonight by the person who loves them most in the world and who has survived to love them as they grow. So this stuff works: campaigning is the key for all of us lucky enough to use our voices.

And on education, I am hopeful we can get even further than we have with the maternal mortality campaign, and achieve all of our goals by 2015. I know that sounds incredibly ambitious – because it means getting 57 million children into school in less than two years. Gordon and I have decided to devote the next years of our lives to this and we intend to be judged by our results. Increasing awareness is great – but if the numbers of children getting a high quality education does not increase in leaps and bounds in the years to come then we collectively will have failed.

Thankfully, we have a lot of help. When Gordon was appointed the United Nations’ Secretary General’s Special Envoy on education, the weight of the UN system was added to our cause. Business leaders have come on board to the Global Business Coalition for Education that I am fortunate to chair, and I am pleased that religious leaders have agreed to form a faith coalition to mobilise the faith communities as has happened so powerfully for debt relief and make poverty history in the past. Most significantly, younger people are lining up at as ambassadors, spokespersons, online champions and community mobilisers – the 600 strong youth leaders from the digital platform A World at School who assembled at the un on Malala Day in July, are all now engaging with their networks, supported by NGOs from around the world. The digital platform is growing rapidly, and the consistent messages, the constant call for action and the rising volume are starting to make a difference. From Syrian refugee children needing a place at school this autumn to young girls wanting to study before they marry in Yemen, Nigeria, Bangladesh to child workers who have never been inside a classroom, the momentum for them is growing.

This grand confluence of forces is powered by the single most important driver of change – every individual who cares enough to take up an action – whether just a tweet or post, or more. It includes you.

Because if we can’t mobilise millions of so-called ordinary people to do hundreds of extraordinary things, the governments of the world will conclude that the pledge they made to get every child into school can be allowed to quietly slip away, the pledge for gender equality ignored, the pledge that every child can be safe from violence, from trafficking and from finding their own voice just disappears. That would be a tragedy not just for the millions of children whose lives continue to be destroyed, but for the notion of progress itself.

If we can’t even rely on our leaders to do that which they have promised to do, can we rely on them to do all that we need them to do? I don’t want my children to grow up in a generation of cynics, a whole group of people who think that promises don’t get kept and politics doesn’t really work. I want them to see and to know that if we make a promise – particularly a promise to a child – we keep it. That when we see an injustice, we right it. That when we are presented with an opportunity we seize it. And that when we have the chance to change the world there is nothing we won’t do to see that potential fulfilled.

That, for me, is the ambitious spirit of activism which Index on Censorship embodies, and the one which we must now bring to bear in ensuring that the girls and women of the world learn first how to read, and then how to lead. This is the chance of our generation and I hope you, like me, think it is one we must grasp with both hands.

This speech transcript was originally posted on 18 Oct, 2013 at indexoncensorship.org