4 Nov 2015 | Artistic Freedom, Index Arts, Magazine, mobile, Music in Exile, Student Reading Lists

Songhoy Blues

To mark the launch of the Music In Exile Fund, Index on Censorship has compiled a reading list of articles that have appeared in the magazine since 1982 and deal with censorship and music. We are offering these articles — which are normally held behind a paywall — for free.

Index on Censorship launched the Music In Exile Fund in partnership with the producers of They Will Have To Kill Us First: Malian Music In Exile – a documentary that follows musicians in Mali after the 2012 jihadist takeover during which music was outlawed. One band’s story featuring heavily in the film is Songhoy Blues, who are just one of many to feature in the Music In Exile Fund playlist.

The fund will contribute towards Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship, a year-long programme to support those facing censorship.

You can donate to the Music In Exile Fund here.

From the Autumn 2010 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

Banned: A rough guide

Marie Korpe and Ole Reitov have been tracking the music censors and the censored for more than a decade. They reflect on the tactics of modern censorship

When we founded Freemuse ten years ago, our aim was to defend freedom of expression for musicians and composers. Since then, we have documented music censorship in more than 100 countries. At first, we were not aware of the size of the problem, but the longer we have worked in the field, the larger the challenges become. Maybe we are still only seeing the tip of the iceberg. While more journalists have got music censorship on their radar and a number of musicians have benefited from our support, it is still rare to find records of music censorship and violations of musicians’ rights to freedom of expression in reports from Amnesty, Human Rights Watch and other global free expression watchdogs.

Read the full article

From the Spring 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

Change your tune?

Some homophobic lyrics in rap and reggae incite hatred and violence,

agree campaigners Peter Tatchell and Topher Campbell. But is

censorship the answer? First, Peter Tatchell explains why education will

help. Then Topher Campbell tells Alice Kirkland where he would draw

the line

Along with misogyny, homophobic lyrics have long blighted some rap and reggae music. Eminem and Buju Banton, among others, have found themselves in the firing line for their incendiary anti-gay hate music, ranging from rap songs containing insults like “faggot” to tracks that overtly glorify and encourage the murder of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people.

Homophobic hate speech is wrong, regardless of whether it is expressed by a bully in the street or by a singer.

Read the full article

From the Autumn 1995 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

To be young, alive and making music

Valrie Ceccherini writing in 1995 as part of a series focusing on the voices of those silenced by poverty, prejudice and exclusion

“My life has changed totally since the war,” says 20-year-old Ermin. He speaks of “the constant presence of death” with resignation. “I live shoulder to shoulder with death. Every time I go out, a missile could kill or wound me. Lots of my friends are dead. I think of them every day and 1 know 1 could join them at any moment. I’ve learned to live with this fear for three years now; there was no choice. I know it’s changed me. I’m harder, braver – or maybe I’ve just gone mad. Everybody here’s changed: everybody’s gone mad. You can’t help it after three years shut up in this hell.”

Emir is a slight youth of 17. “I used to spend most of my time away

from home, out with my friends. Now I scarcely ever leave home. It’s too dangerous.”

Read the full article

From the Autumn 2010 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

Will Self on God Save The Queen

In the summer of 1977 I was 15 years old and wore an old tropical linen jacket I’d bought in a charity shop for a quid. It wasn’t so much off-white as ruinous, and it matched the colour of my shoes – winkle-pickers I’d painted myself using some kind of weird leather paint. Naturally I had to lie on my skinny rump to force my El Greco feet through the eight-inch ankles of my drainpipe jeans. Given all this sartorial mayhem it goes without saying that I absolutely concurred with the Sex Pistol’s front man, Johnny Rotten, when he sang, “God save the queen / The fascist regime”. Admittedly the causal connective “it’s” was lost in all the filth and the fury of his delivery, but we knew what he meant.

Actually, I can barely remember the circumstantial pomp that went into the celebration of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, all I can recall is the Sex Pistols’ treasonable ditty, and the fact that it was banned from being played on the radio. At least I’m certain it was banned from the BBC’s Radio 1.

Read the full article

From the Winter 1998 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

Tales of Terezín

Mark Ludwig for Index on Censorship on how the Nazis used music as a propaganda tool in the service of its doctrine of racial purity and superiority. Composers and musicians who did not fit the formula found themselves In the camps

In the 1920s, Weimar Germany was home to a rich and diverse mix of artistic and political movements. Composers stretched the boundaries of, and in some cases charted new courses for, classical music. Zeitmusik (music of the time), the 12 tone system and jazz were part of a new and excitingly diverse web of musical movements. As Hitler and the Nazi Party assumed control of Germany, the arts and the political climate were affected. Under the Nazi dictatorship, the arts – particularly music – were used as tools for indoctrinating and controlling the German nation with an ideology of national superiority, suppression and racial hatred.

Read the full article

From the Spring 1993 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

Pop go the censors

David Holden for Index on Censorship in 1993 on how anything — well almost — goes on the UK pop scene, but in the USA it’s a different story with Ice-T and the rappers sending shivers down parental spines

“Big boys bickering/fucking it up for everyone,” goes Paul McCartney’s 1992 song Big Boys Bickering. It’s an ecological song; the big boys bickering were the people at the Rio Earth Summit. About the song, McCartney has said: “When you talk about a hole in the ozone layer, you don’t talk about a flipping hole in the ozone layer, you talk about a fucking hole in the ozone layer. I know it might upset some of my fans, but I’m an artist, and I’m 50 years old and I think I can say what I like.”

Not on MTV America, Paul. According to the pop video channel, The Greatest Living Songwriter — faithful husband, caring parent, concerned citizen — is once again unsuitable for the youth of the USA.

Read the full article

From the Winter 1983 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

Banned in Bohemia

Vratislav Brabenec and Ivan Jirous tell the story of The Plastic People, a rock band which was seen as a threat by the Czech authorities during the Cold War

“Why should music be censorable?” asks Yehudi Menuhin on another page. Elsewhere in this issue the reader will see that in some parts of the world even certain musical instruments can be declared taboo by this or that military dictatorship. In Czechoslovakia since the early seventies it has been chiefly rock music that arouses the ire of the authorities – and those who insist on playing it find themselves not just banned but imprisoned.

Ah, but of course, one might say: if you set out to be a protest singer in a society ruled by a one-party dictatorship, what do you expect? The trouble with that line of argument is that The Plastic People of the Universe and the other rock groups with similarly strange names were not protest singers at all.

Read the full article

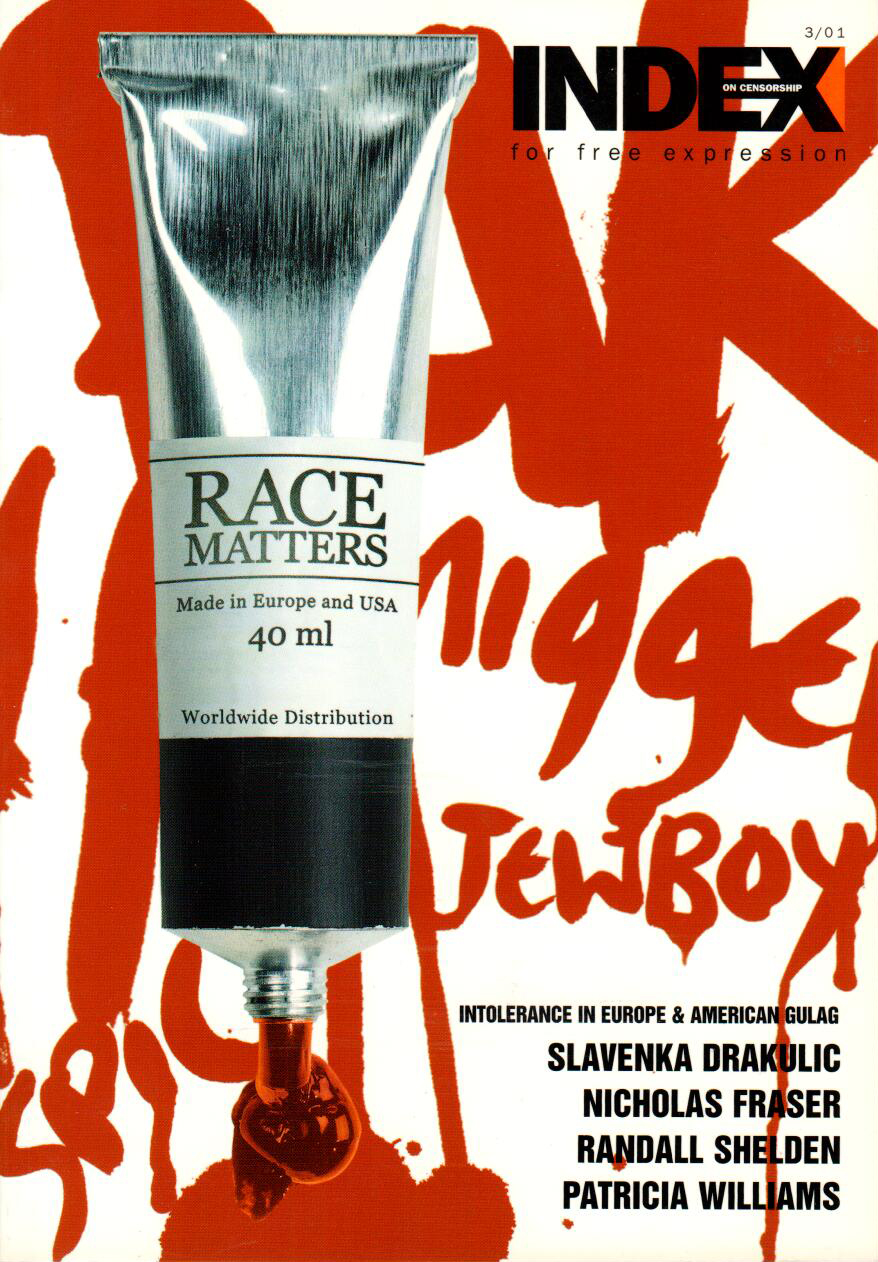

From the Summer 2001 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

Music to hate with

Aided by the Internet, racist music has made inroads on European youth culture, says Heléne Löow

It was in the first half of the 1990s that White Noise music became the symbol of the growing racist subculture around Europe. Between 1990 and 1995, the music industry, then in a period of rapid expansion, gradually replaced the badly copied tapes, records that were hard to come by and roughly photocopied magazines with professionally produced CDs. The number of CDs on the market grew steadily; production became increasingly professional with Swedish White Noise record labels among the world’s most active producers.

By 1996, the first phase was over; for the next two years, production maintained its levels but there was no significant increase. By 1999, however, it was once more on the rise, along with white-power magazines, and other propaganda material.

Read the full article

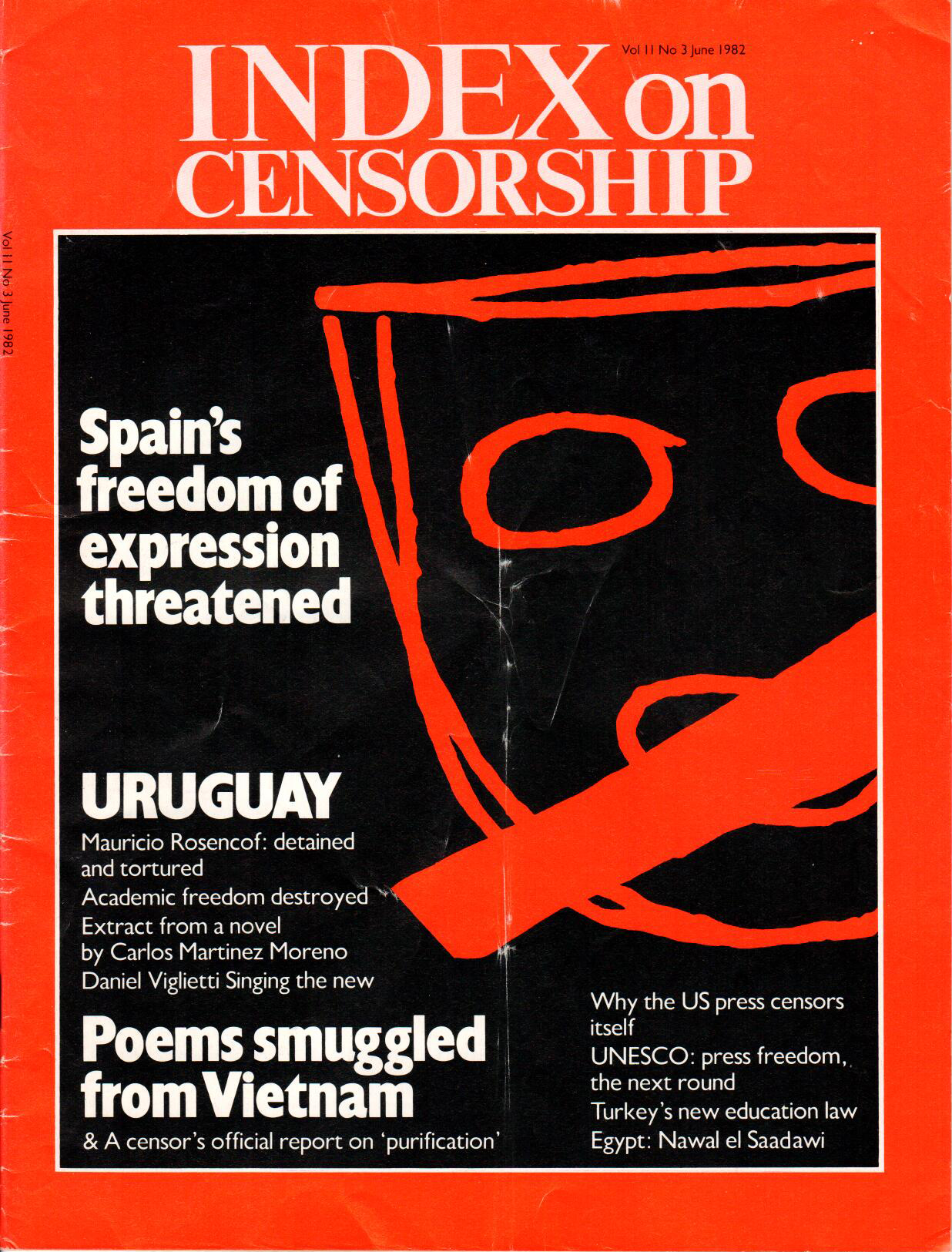

From the Summer 1982 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

Singing the new

One of Uruguay’s best-known singers talks to Daniel Viglietti about his life in exile

I was first invited to this conference to participate, together with the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano, in an event in which song and literature would work together, bringing together a man like Galeano, who writes with a pen, with someone like me, who, if you would allow me, writes with a guitar. Later on, the organisers phoned me to ask if I would add some thoughts about exile. I agreed to that, since I have been living in that situation now for eight years and one month. Given the nature of this occasion, I have attended some meetings handicapped by the fact that I do not speak English. For this kind of contribution, I need my mother tongue, Spanish. Today I have the advantage of a translation so I am going to throw out some ideas about the exile in which hundreds of thousands of Uruguayans have been living for eight, nine or even 10 years.

Read the full article

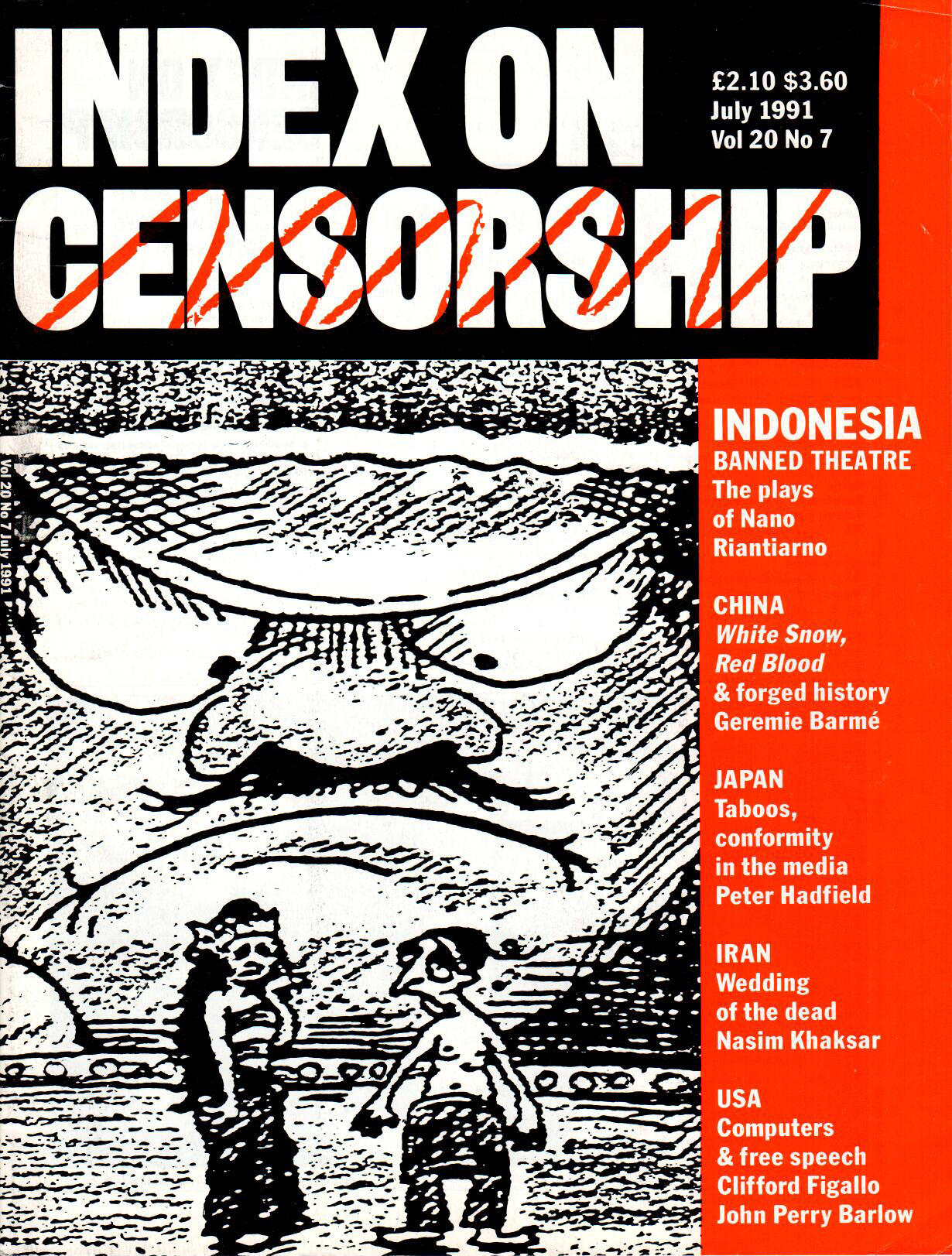

From the Summer 1991 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

Chile: Cleansing the past

Nick Caistor on the Report of the Commission for Truth and Reconciliation, which revealed for the first time the details of how Chilean musician Victor Jara died

Victor Jara was one of the best-known singers and theatre directors during Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government in Chile. From 1970 to 1973, Jara sang for the people and put on shows in shanty towns and factories, determined that popular culture should be at the heart of the government’s efforts to take Chile along its ‘path to Socialism’.

Shortly after the military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet on 11 September 1973, Victor Jara was taken prisoner. With hundreds of other suspects, he was held in the Chile stadium in the capital, Santiago. He was last seen alive as he was being transferred from there to the National Stadium on 15 September 1973.

Read the full article

13 Oct 2015 | Events, mobile

Structured around and spurred on by the spirit of interrogation, Question Everything is an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia.

Are we in a drought of new options? Start imagining the world anew with a series of dissident provocateurs asking challenging questions and interrogating the opinions we trust, the systems which govern us and the things we take for granted.

Dissent encouraged. Be prepared not to agree.

With dissenters including:

• Brett Scott (author of The Heretic’s Guide to Global Finance).

• Ellen Quigley (University of Cambridge Ethical Investment Working Group).

• Francesca Martinez (comedian).

• Gary Anderson & Lena Simic (artists, The Institute for the Art and Practice of Dissent at Home)

• Hamid Ismailov (Uzbek journalist and writer).

• Heydon Prowse (satirist, The Revolution Will Be Televised)

• Mel Evans (author of Artwash: Big Oil and The Arts, activist Platform London & Liberate Tate).

• Noemi Lakmaier (artist).

• Peter Tatchell (activist).

• Tassos Stevens (artist, Coney).

• Priyamvada Gopal (Faculty of English, Cambridge).

• Thomas Jeffrey Miley (Department of Sociology, Cambridge).

Compered by Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship.

When: Sunday 25 October, 1:00pm – 6:00pm

Where: Cambridge Junction, Clifton Way, CB1 7GX (Map)

Tickets: £5 from Cambridge Junction

Question Everything is a highlight of the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, which has the theme of ‘power and resistance’. This event is a co-production by Index on Censorship, the Junction Cambridge and Cambridge Festival of Ideas.

23 Sep 2015 | Magazine, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by Max Wind-Cowie on free speech in politics, taken from the winter 2014 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the Elections – live! session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

We are often, rightly, concerned about our politicians censoring us. The power of the state, combined with the obvious temptation to quiet criticism, is a constant threat to our freedom to speak. It’s important we watch our rulers closely and are alert to their machinations when it comes to our right to ridicule, attack and examine them. But here in the West, where, with the best will in the world, our politicians are somewhat lacking in the iron rod of tyranny most of the time, I’m beginning to wonder whether we may not have turned the tables on our politicians to the detriment of public discourse.

Let me give you an example. In the UK, once a year the major political parties pack up sticks and spend a week each in a corner of parochial England, or sometimes Scotland. The party conferences bring activists, ministers, lobbyists and journalists together for discussion and debate, or at least, that’s the idea. Inevitably these weird gatherings of Westminster insiders and the party faithful have become more sterilised over the years; the speeches are vetted, the members themselves are discouraged from attending, the husbandly patting of the wife’s stomach after the leader’s speech is expertly choreographed. But this year, all pretence that these events were a chance for the free expression of ideas and opinions was dropped.

Lord Freud, a charming and thoughtful – if politically naïve – Conservative minister in the UK, was caught committing an appalling crime. Asked a question of theoretical policy by an audience member at a fringe meeting, Freud gave an answer. “Yes,” he said, he could understand why enforcing the minimum wage might mean accidentally forcing those with physical and learning difficulties out of the work place. What Freud didn’t know was that he was being covertly recorded. Nor that his words would then be released at the moment of most critical, political damage to him and his party. Or, finally, that his attempt to answer the question put to him would result in the kind of social media outrage that is usually reserved for mass murderers and foreign dictators.

Why? He wasn’t announcing government policy. He was thinking aloud, throwing ideas around in a forum where political and philosophical debate are the name of the game, not drafting legislation. What’s more, the kind of policy upon which he was musing is the kind of policy that just a few short years before disability charities were punting themselves. So why the fuss?

It’s not solely an issue for British politics. Consider the case of Donald Rumsfeld. Now, there’s plenty about which to potentially disagree with the former US secretary of state for defense – from the principles of a just war to the logistics of fighting a successful conflict – but what is he most famous for? Talking about America’s ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, he thought aloud, saying “because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know.” The response? Derision, accompanied by the sense that in speaking thus Rumsfeld was somehow demonstrating the innate ignorance and stupidity of the administration he served. Never mind that, to me at least, his taxonomy of doubt makes perfect sense – the point is this: when a politician speaks in anything other than the smooth, scripted pap of the media relations machine they are wont to be crucified on a cross of either outrage, mockery or both. Why? Because we don’t allow our politicians to muse any longer. We expect them to present us with well-polished packages of pre-spun, offence-free, fully-formed answers packed with the kind of delusional certainty we now demand of our rulers. Any deviation – be it a “U-turn”, an “I don’t know” or a “maybe” – is punished mercilessly by the media mob and the social media censors that now drive 24-hour news coverage.

Let me be clear about what I don’t mean. I am not upset about “political correctness” – or manners, as those of us with any would call it – and I am not angry that people object to ideas and policies with which they disagree. I am worried that as we close down the avenues for discussion, debate and indeed for dissent if we box our politicians in whenever they try to consider options in public – not by arguing but by howling with outrage and demanding their head – then we will exacerbate two worrying trends in our politics.

First, the consensus will be arrived at in safe spaces, behind closed doors. Politicians will speak only to other politicians until they are certain of themselves and of their “line- to-take”. They will present themselves ever more blandly and ever less honestly to the public and the notion that our ruling class is homogenous, boring and cowardly will grow still further.

Which leads us to a second, interrelated consequence – the rise of the taboo-breaker. Men – and it is, for the most part, men – such as Nigel Farage and Russell Brand in the UK, Beppe Grillo in Italy, Jon Gnarr in Iceland, storm to power on their supposed daringness. They say what other politicians will not say and the relief that they supply to that portion of the population who find the tedium of our politics both unbearable and offensive is palpable. It is only a veneer of radicalism, of course – built often from a hodge-podge of fringe beliefs and personal vanity – but the willingness to break the rules captures the imagination and renders scrutiny impotent. Where there are no ideas to be debated the clown is the most interesting man in the room.

They say we get the politicians we deserve. And when it comes to the twin plaques of modern politics you can see what they mean. On the one hand we sit, fingers hovering over keyboards, ready to express our disgust at the latest “gaffe” from a minister trying to think things through. On the other we complain about how boring, monotonous and uninspiring they all are, so vote for a populist to “make a point”. Who is to blame? We are. It is time to self-censor, to show some self-restraint, and to stop censoring our politicians into oblivion.

© Max Wind-Cowie and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas, featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the winter 2014 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

23 Sep 2015 | Magazine, Volume 37.03 Autumn 2008

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by author Conor Gearty, on politics and extremism, taken from the summer 2008 magazine. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the Can writers and artists ever be terrorists? session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

I object to the ‘age of terror’ title. My anxiety about this is that it is already putting people like me at a disadvantage. I am forced to work within an assumption, which is shared by all normal, sensible people, that we live in ‘an age of terror’. Therefore the point of view that I am about to put – about the total appropriateness of the criminal law; about the relative security in which we live; about the fact of our being pretty secure in comparison with many previous generations – is deemed to be sort of eccentric, if not obstructive. This language has made impossible my victory in the competition for common sense. So I concede we live in a certain age, with misgivings, but I want to call it an age of counter terror. We live in an age during which it has suited certain elements within the culture to talk up, and reflect in law, a concern with a type of criminal violence that warrants legal form in the shape of counter-terrorism laws.

If you are still concerned about the ‘age of terror’, have a look at the FBI’s compendious analysis of terrorism 2000 to 2005 in the United States. You will find references to the occasional environmental activist who has attacked a tractor; you will find detailed analysis of the very occasional intrusion into animal experiment laboratories by this or that criminal tendency committed to the safeguarding of animals; you will find, in other words, a tremendous amount of space devoted to very little. You will find an organisation that is trying to supply an empirical basis for something without very much conviction. That’s why, frankly, the minister of security [Tony McNulty] says [when I asked if there’s empirical evidence for the decision to increase the length of detention without charge to 42 days]: ‘Honestly, no, I won’t provide an empirical basis,’ rather than attempt, in an increasingly embarrassing way, to deliver one.

This ‘age of terror’ depends on a hypothesis about the future, not about the facts of the present, and it is this that makes it so dangerous. The moment you are manoeuvred into a position where you are forced to debate somebody about civil liberties or human rights on certain imprecise assumptions about the future, which have to be taken on trust, then that is the moment when you have lost the debate. So I am extremely anxious about this.

Now moving on to the substance, the second of the terms we have here in this conference title: ‘free speech’. Well, it’s clear, and the minister reminded us, though I thought he took a reckless point because he said, ‘It would be quite wrong to shout ‘‘fire’’, here.’ Well, the usual, conventional example is that it would be wrong to shout fire in a crowded cinema, of course. And we have to tell the students this (and very few teachers do) – unless, that is, there is a fire! You have this real concern that a lot of students who studied constitutional law go to cinemas and there is a very small fire breaking out and they’re thinking to themselves, ‘Oh my God, but didn’t my professor say ‘‘don’t shout fire?’’ ‘ So a little knowledge can be a very dangerous thing. So I felt like intervening with the minister, but as he said himself, his answers were nearly as long as my questions – so I couldn’t.

Of course there has been control on speech in democratic society, but we are not that interested in that today; we are interested in a different kind of thing about which there is also an extremely long record – control on political speech in a democracy. Now, it is completely wrong to think of democratic countries as not having control on political speech. It has been ever thus. Most recently, and controversially, there are debates about race hate and religious hate, and those are the most obvious recent examples of controls on speech that emanate out of a democratic culture.

An obvious one, which reminds us that so much of this depends on context, is Holocaust denial. The president of Rwanda, Paul Kagame, spoke at the centre I direct, the Centre for the Study of Human Rights at the London School of Economics. It was a fairly controversial speech, and he got asked about his controls on the press, and in particular about new laws concerning the control of genocide denial. Of course it was asked by an American student for whom this sort of control is often anathema. His answer was: ‘They seem to have it in Switzerland and it does not cause any trouble; in Germany it does not cause any trouble; and it is not going cause any trouble in my country – because we need it.’ In other words, what the president was saying was that democratic cultures make judgments about what is necessary in their own culture and that this drives a great deal of control, not only of speech, simpliciter, but of political speech as well.

Now, in this country, when we talk about controls on extremism, I would say, we are talking about controls on political points of view that are put without any linkage to violence. That too has been a recurring theme in this society, in the entire democratic era. You might say the democratic era starts in 1929 or in 1919. It could even begin, if you had forgotten about the working class, in 1832. But since its inception, we have had control on political speech – and not just during both wars when it was severe. (In the Second World War, parenthetically, Churchill had to order a review of the magistrates’ cases in which anxious judges were throwing people in jail for causing despondency among the public. There was a fantastic debate in the House of Commons, where Churchill, as prime minister, said something along the lines of: ‘We are fighting for freedom, civil liberties and the rule of law, these magistrates have over interpreted the laws we passed, we have to stop them.’) Apart from the wars, in the 1920s, people of the Communist Party here were convicted of sedition. Their conviction was really of membership to the Communist Party, but sedition was the legal form. In 1934, an Act of Parliament was passed called the Incitement to Disaffection Act, which criminalised attempts to persuade the army of the rightness of the socialist cause. In the 1950s and in the 1960s there were political prosecutions under the official secrets legislation that was designed to tackle extremism – which then took the form of radical-left political speech. We have had it in the entire democratic era – so what’s new?

I’ll come to what’s new about the so-called ‘age of terror’, through the so-called terrorism problem – which was of course originally the Irish problem. There have been some references here to this, this afternoon. Memories seem to be extremely short. The legislation was mentioned in the Q&A with the minister. Throughout the problem of political violence in Northern Ireland, there were frequent examples of journalists being at the foreground of efforts by government to attack the peaceful purveyors of political points of view – and in particular to attack the messengers who covered incidents which were of concern to the government. In 1979, for example, Newsnight was compelled by pressure not to broadcast film it had of an IRA action in Carrickmore. In regards the attack on members of the British Army in West Belfast, there were orders that required the media to return its filming of those events, with a view to facilitating prosecution. There was an ABC news crew, which was headed by Pierre Salinger, which was arrested in Northern Ireland. There were frequent controls on the press. There was, it is said, the punishment of Thames TV, through the non- renewal of its franchise – I don’t know if it is the case – for having the temerity to broadcast Death on the Rock, a report that exposed the events in Gibraltar that led to the death of three members of the IRA. There was, above all, the media ban in 1988. A ban not only, as would have been claimed at the time, of IRA members, who were already prevented from appearing on television or radio as a result of proscription introduced in this country in 1974, but of persons who shared the political objectives of the Provisional IRA.

Now this is the point about chill, which is relevant: with the media ban in place, Mr McNulty, or the equivalent of the day, naturally says ‘We do not intend to destroy free speech; we are sending out signals of support for freedom.’ The reality is, however, that news editors, nervous members of the university computer department, radio talk shows and producers are not scrutinising the media ban, they’re not looking at the Internet – they are thinking there is a law that stops me doing ‘this’, but they are vague and anxious about what the ‘this’ is that they refuse to do. It is back to the magistrates during the Second World War. It is the broadcasting of a pop song, by the Pogues for example; it is the refusal to have an interview with persons pushing for the point of view that the Birmingham Six and Guildford Four have not been lawfully imprisoned because their convictions are unsafe and unsatisfactory. The ‘this’ is actually not the violent extremists being prohibited; the ‘this’ are the people on the wider periphery of the same mission, who find that their ability to enter into the public arena for discussion and debate is being undermined by the drive from within government to address so-called extremism.

Now, the United States is very well versed in this – the country with a strong supposed commitment to free speech that has forced out of existence leftist opinion within the country – so it is not all about law. In the United States, it is called the chill factor. And what we learn from the past – moving now to the contemporary, so-called ‘war on terror’ – is the danger of the chill factor, the danger of fear driving a liberal culture onto the defensive and making normal the repression that flows out of that fear. We had the surfacing of an extreme example when, in the immediate aftermath of the 7 July bombings, the government formed the view that it would be important to prevent the celebration of terrorism actions. You may remember in what is now the Terrorism Act 2006, Section 1, there was a brief period when there was a Terrorism Bill which had the plan of having a schedule of things you could celebrate and a schedule of things you couldn’t. So, if you rather fancied celebrating Cromwell for having chopped off the head of a King, that was okay. There was a period where it looked as though you could celebrate the 1916 Easter Rising, but you couldn’t celebrate anything to do with Islam. You couldn’t celebrate the removal of the Shah of Iran, for example, because it is about power – and the powerful are able to determine what they can celebrate and what they cannot. Now, this was removed, because debate exposed it as absurd, but the ‘power’ point remains.

The powerful have erected their current position usually off the backs of violence – not necessarily their own violence, but the violence of their predecessors – and they can celebrate that violence without fear, because they have the power to control the system. But those who have no power in the culture, those who critique the effect of the exercise of power on them, their rival stories of resistance to oppression, of colonial liberation, are condemned as the celebration of terrorism.

Now, finally, what’s different about this current age of terror, the extremism of today? Well, the IRA problem was one that produced in the end a solution; and it was always understood that there was the possibility of a solution. My real concern about this stuff, about the age of terror, is not the word ‘terror’ but the word ‘age’. It is a new situation from which we cannot remove ourselves. It requires no enemy. If you haven’t recently read George Orwell’s 1984, go back to it and read bits of it with this in mind. The unknown enemy who cannot be named, much less found, who never appears to fight back. We know, yes, there are 16 or 17 terrorist plots in the UK or 20 or 22 we are sometimes told, we don’t know whether it is the same number as last year or whether this has changed. Now, I can’t question the Secret Service’s briefings. For all I know these plots do exist. But there is a driven quality to this – a drive for a re- organisation of our culture, away from the commitment of liberal values and in the direction of the commitment of security, which I think is quite important.

One of the reasons why the 42-day detention period matters so much to me, is because opposition to it is a very strong signal that law should not be made on the basis of undisclosed fears about an uncertain future. And it is a blank cheque to the powerful – to push through everything that they desire off the back of that. I wonder what you thought about Mr McNulty’s response about his proposed objections to an extension to 90-days detention in three years, when a Conservative strongman of some sort or other is home secretary and there is a further push for yet more law? How can Labour oppose such a law? The culture will have shifted, with both of our main parties now in favour of extreme legislation on the basis of future threat. We will have lost something important, something liberal, in our political community.

I know that I haven’t dealt with law, which is also in the title, but it is on this point about the culture that I want to end. Do not look to law to dig you out of this hole if you believe in free speech, if you believe in a democratic culture that involves freedom for the powerless as well as for the powerful. Law usually sides with the powerful; law has always done so in this country, apart from one or two occasions, which are then paraded as evidence of the truth. Exceptions do not make rules; exceptions show the existence of the rules. In the 1930s, all the executive and police repression was upheld; in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s as well; the media ban was upheld in the House of Lords in the late 1980s. The stop and search powers in Section 44 of the Terrorism Act 2000, which the minister acknowledges are being used too broadly, have been upheld by the House of Lords, in a recent case, Gillan v the Metropolitan Police Commissioner. So don’t be misled by avuncular old men being profiled in the liberal press. There are one or two exceptions, but do not rely on law to dig you out of this hole. Rely on political action, rely on generating enough head of steam to preserve our liberal values, so that it becomes common sense – not for Mr McNulty, not for the Mr McNulty of two or three years, when he is trying to rebuild his relationship on the left, but common sense for the McNultys of today, or the Lord Goldsmiths of last year. The culture will be more secure when people, like Churchill during the war, commit to free speech when they are in power and not only when they have left office.

© Conor Gearty and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the summer 2008 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine, with a special report on propaganda and war. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.