1 Apr 2019 | Awards, Awards Update, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

2018 Freedom of Expression Journalism Award-winner and 2018 Journalism Fellow Honduran investigative journalist Wendy Funes at the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

“Despite my fears and the pain that violence has left in my country, it has been wonderful to see that it has been worthwhile to dream in a world with so much solidarity,” Wendy Funes, winner of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship for Journalism, told Index on Censorship.

Freedom of expression has suffered a steep decline in Honduras, a country where 70 journalists have been killed over the last nine years, with Gabriel Hernández’s murder on 17 March marking the first of 2019. Wendy Funes, an investigative reporter who runs her own online news website, Reporteros de Investigacion, is one of the few remaining journalists in the country that continues reporting and investigating issues despite the immense pressure to remain silent.

As a woman journalist in Honduras, a country in which gender-based violence is a serious issue, as is violence against journalists, Funes finds it important to attend events for women in leadership, such as the one she attended in Mexico City with the Center for Women’s Global Leadership.

“It helped me to realise that I am not alone in the continent and to know that there are other places with women who are specialised and do methodical and rigorous work,” said Funes.

Although she has faced a great deal of adversity as a woman journalist, Funes considers herself lucky having been given the opportunity to study and have a career in journalism, when seven out of every ten Hondurans live in poverty, with more than a million children without access to school and a small percentage of people who finish high school.

2019 is proving to be a busy year for Funes as she undertakes a new project, Sembrando el Periodismo de Investigacion en Honduras, with the help of a grant from National Endowment for Democracy. The project consists of four major investigations, two of which Funes and her team are currently working on.

The first is an investigation into the Trans 450, a transmetro that was promised to Hondurans and cost them $9 million, but has not been put into operation yet. The second investigation examines the impunity on aggressions against freedom of expression.

“The NED project is our first significant project and the support and respect they have shown for our work is really important to us,” said Funes.

The biggest project Funes has planned for the future, however, is the building of a Centre for Investigative Journalism that will be the first centre of its kind in Honduras.

“We want the office to become a training space for press and media professionals, advocates, professionals from universities, and academics who wish to learn,” said Funes.

In preparation for building the centre, Funes and her team are working with Factum magazine of El Salvador to train journalists and students. They will hold the first workshop in April of this year and the hope is that they will develop a network of journalists that will then serve as the foundation for the Centre for Investigative Journalism.

“For now, our priority is to strengthen our office and our business model, to nurture alliances and strengthen the network that will one day become the centre we are talking about,” said Funes.

Being an Index fellow has opened up many new opportunities for Funes, but has also renewed her own sense of confidence in herself as a woman and as a journalist.

“Index appeared in my life as a gift of providence and helped me at a very fundamental moment because the award coincided with the year I made the decision found my own newspaper,” said Funes. “They showcased me and my work and many more people followed in encouraging and supporting me.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1554114253076-1aebf9f6-f8dd-7″ taxonomies=”10735″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 Sep 2018 | Awards, Awards Update, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, Media Freedom, News and features

“There have been deaths in the country, there are members of the military involved in extrajudicial executions, there is a culture of murdering people.” This is what Wendy Funes, winner of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship for Journalism, tells Index about the dangers of reporting critically of Honduras’ authorities.

Such risks don’t deter Funes, whose online news outlet, Reporteros de Investigacion, reported on 8 June 2018 that members of a Honduran military unit allegedly engaged in inappropriate behaviour towards young female students. The unit was conducting seminars in schools on the dangers of drugs and collecting the personal information of pupils without parental consent. In at least one case, a member of the unit was texting sexually harassing messages to who he thought was a pupil, but was actually the pupil’s mother.

Two days later, a fake article claiming that the military programme was pushing gangs out of schools was being shared on WhatsApp groups. The piece used the Reportero de Investigacion logo.

“I didn’t think this type of story would receive such a response — which is one of the mildest that has ever happened to me — because I know the capacity in which the military operates,” Funes says. “The murder of journalists is a big problem — murdered women have been found in the cars of military officials and staff — and impunity only makes these killings easier to carry out.”

Funes says journalists with a high profile and who are seen to be an “inconvenience” are most at risk, especially “young people who adhere to certain stereotypes of rebelliousness”. Reporteros de Investigacion draws a large readership in what is one of the world’s most dangerous places to be a journalist.

Soon after the exposé on the military, a failed cyber attack was made on the publication’s website. “They weren’t able to compromise our digital security,” Funes says. She reported the attack to the Mecanismos de Protección Ciudadana (Citizen Protection Mechanisms), a government body tasked with protecting fundamental rights, including protection for journalists and human rights defenders. “Progress has been very slow and it hasn’t received very much attention,” she says. “The state has begun an investigation and has named a prosecutor, Luani Alvarado, but she is one of the prosecutors that I have been denouncing because she has repeatedly refused to grant me information.”

Funes was offered a police escort, but being aware of abuses by the police and military — not least those cases exposed in her own publication — she refused.

Such a pressurised media environment exacerbates the problem of self-censorship among Honduras’ journalists. Funes puts the blame on fear. “I lived it when I was working for the monopoly media corporations; I self-censored, as did a lot of my colleagues, in order to be able to keep working in these companies,” she says, explaining that the reasons differ from region to region. “Journalists in the Atlantic coast self-censor for the fear of organised crime, and in other places they self-censor when there are protests, because of the risk or danger this might put them in.”

The solution, she says, has very little to do with the actions of journalists and a lot to do with changing the environment in which they work. “When there is democratisation, when the owners of the media respect the thoughts and views of the journalist and when journalists come out of journalism school better prepared for these situations, then we will defeat self-censorship,” she says. “If the structure does not change, we can not talk about concrete things.”

Funes wants to put an end to censorship overall, which she says has let her country down so many times. Working with her in this aim, Index helped her secure the funding to provide legal support for Reporteros de Investigacion. “We needed a legal society that is able to accept funds and other means of sustainability, which cost money, and that’s where Index came in, helping us raise the seed capital,” she says. The publication is now partnered with Investigaciones y Comunicaciones (Indica) and can engage in commercial activities.

“It has been an emotional moment,” Funes says. “Our plan is to grow at a slow but firm pace, and our dream to found the first centre for investigative journalism in Honduras.” The next step is to register with the chamber of commerce in Tegucigalpa.

The publication relies on the work of volunteers and so being financially self-sustainable is a key aim. “Once we can achieve that this, more doors will open — in addition to the ones Index has already opened for us,” Funes says.

Index has also helped Funes develop a strategic plan and other tools for institutional development. Funes and her team are currently working on at least eight investigations, including challenging Honduras’ white-collar crime culture, which has “caused so many problems for the most vulnerable in society”.

Working to sustain both herself and her newspaper takes much physical and emotional effort, which can be very difficult as her days are always full. In addition to her reporting, Funes is also working towards a master’s degree in criminology and has enrolled in an investigative journalism course. “Contact with Index has helped me to be self-critical and improve every day,” Funes says. “My country deserves it, which is why I educate myself. And I hope all these sacrifices have a reward.”

“Given the criminal culture that exists in Honduras, we have been made invisible and have been ignored, but the recognition from Index and international support networks has been a motivator and helped us rediscover the value of doing journalism that is ethical, honest and rigorous.”

13 Aug 2018 | Americas, Artistic Freedom, Awards, Cuba, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

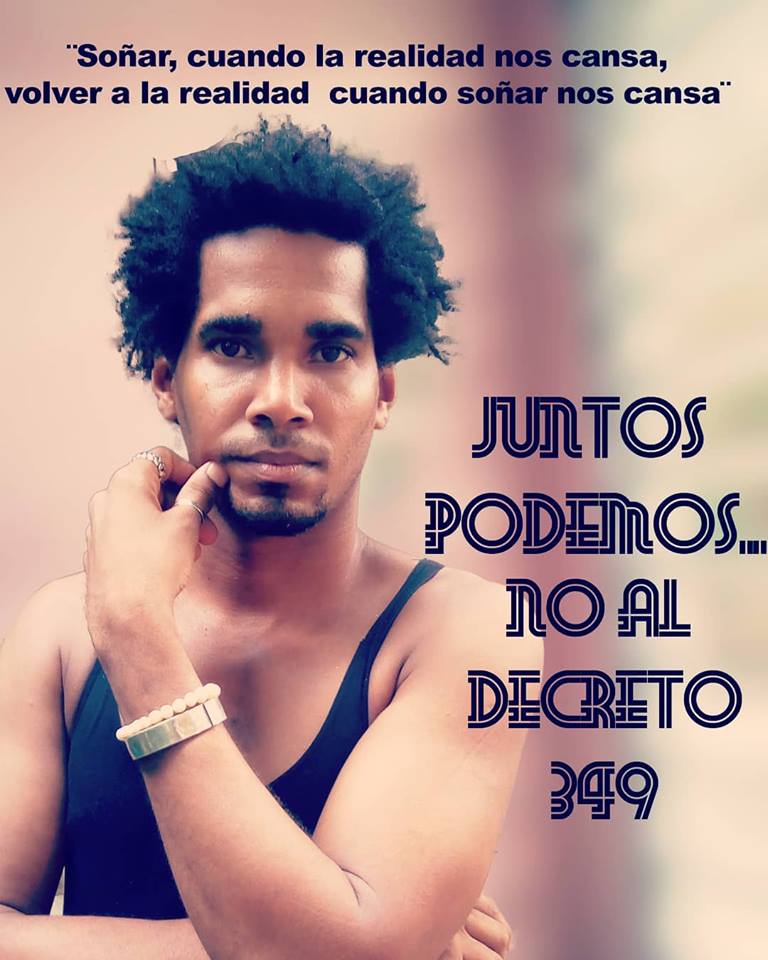

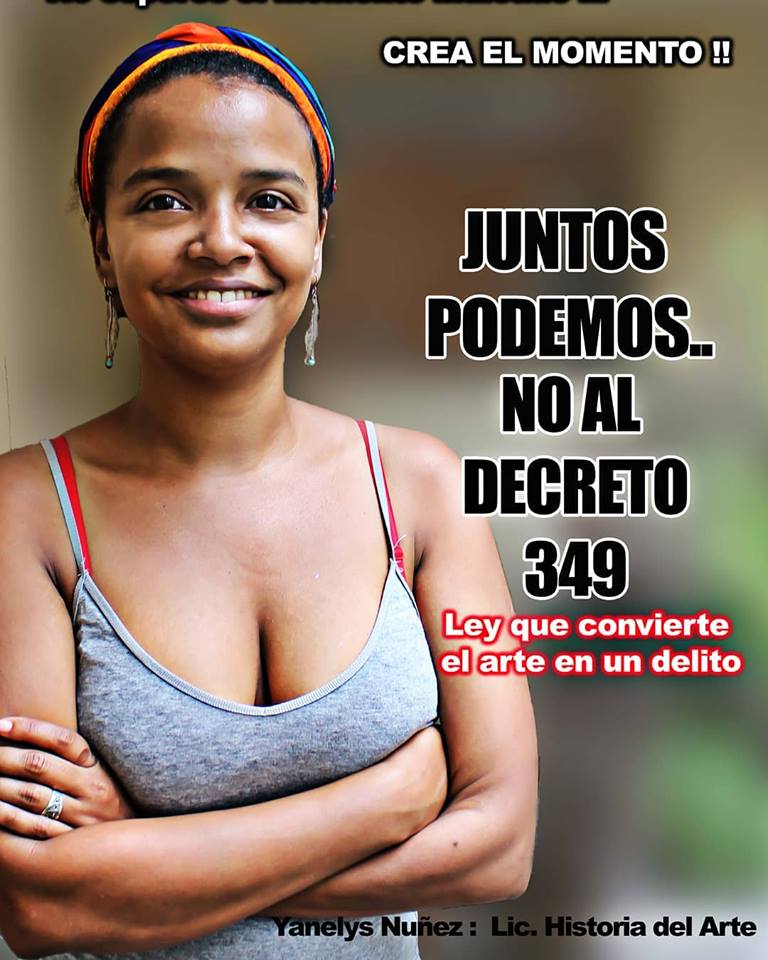

Cuban authorities arrested artists Yanelyz Nuñez and Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara from Otero Alcantara’s home sometime before 6:30am on Saturday 11 August for their role in organising a concert against Decree 349, a law allowing the government to sanction what art can be displayed or exchanged.

The pair are members of the Cuban artists collective the Museum of Dissidence, winners of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship for Art.

In a series of Facebook posts early that morning, friends and family said they didn’t know their whereabouts or what happened to them, stating that they had “disappeared”. Authorities denied knowing where they were.

It wasn’t until their release at 9:36pm that it was clear what had happened to them. During their time in detention, they were beaten and interrogated. Upon release, Otero Alcantara said: “Tomorrow we will continue the fight against the Degree 349.”

https://www.facebook.com/100014484485777/videos/439322859893860/?id=100014484485777&hc_ref=ARTkpBsSsWCxH2UFSnZDqPNuGBLHANFYaZ7uRKiRY55loJSDJPfAJvgxXpP416EHL0g

The meeting place for the concert was Otero Alcantara’s home, but when artists began arriving at around 8:50am they found the street had been blocked by police, who began beating participating artists, 30 of whom were also arrested. While this was happening police had surrounded the home and were intimidating Luis Manuel’s mother.

“We stand in solidarity with the brave artists and activists who, despite clear repression, stand up for fundamental human rights of Cubans,” Perla Hinojosa, fellowships and advocacy officer at Index on Censorship, said. “Arrests, violence and intimidation should never be responses to self-expression, and we call for such acts of censorship to stop. Any law that makes art a crime is unjust and we urge our supports to sign the petition against Decree 349.”[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index works with the winners of the Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship to help them achieve goals through a 12-month programme of capacity building, coaching and strategic support.

Through the fellowships, Index seeks to maximise the impact and sustainability of voices at the forefront of pushing back censorship worldwide.

Learn more about the Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index encourages an environment in which artists and arts organisations can challenge the status quo, speak out on sensitive issues and tackle taboos.

Index currently runs workshops in the UK, publishes case studies about artistic censorship, and has produced guidance for artists on laws related to artistic freedom in England and Wales.

Learn more about our work defending artistic freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1534159774557-297bf371-9804-2″ taxonomies=”23772″][/vc_column][/vc_row]