7 Oct 2016 | Bahrain, Event Reports, Middle East and North Africa, mobile, News and features

Nabeel Rajab, BCHR – winner of Bindmans Award for Advocacy at the Index Freedom of Expression Awards 2012 with then-Chair of the Index on Censorship board of trustees Jonathan Dimbleby

On Thursday 6 October, Index on Censorship gathered outside the UK’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office with English Pen and the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy to hold a vigil for imprisoned Bahraini human rights advocate, Nabeel Rajab.

The 2012 Index on Censorship award-winning Rajab has been in prison since 13 June of this year for comments he made on Twitter. These included details of the torture allegations at Bahrain’s Jau prison and criticisms of the Saudi war in Yemen.

Rajab faces up to 15 years in prison for “denigrating government institutions” and “publishing and broadcasting false news that undermines the prestige of the state”.

Originally Rajab’s sentencing was set for 6 October but has recently been postponed until 31 October. Since 25 September, Rajab has been held in solitary confinement in the East Riffa Police Station despite his health problems and the deplorable conditions.

The protest took place outside the FCO because although it has voiced “concern” over the re-arrest of Rajab it has not called for his release. At the Human Rights Council in Geneva, the UK stated that while it is “concerned” by recent human rights violations in Bahrain, it will continue to provide technical assistance to Bahrain.

It was recently announced that Prince Charles is to visit Bahrain in November. This followed Queen Elizabeth’s sitting beside the king of Bahrain this past spring for her 90th birthday.

While Rajab’s fate is still unknown considering the postponement of the trial until 31 October, the support for Rajab cannot cease. Bahrain has a long history of targeting Rajab in his human rights pursuits, and the UK cannot allow this to continue.

17 Aug 2016 | Academic Freedom, Bahrain, Campaigns -- Featured, Middle East and North Africa, mobile, News and features

Protesters in London demand the release of Abduljalil al-Singace, July 2015.

One year has passed since Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley sent a copy of the publication – Fired, Threatened, Imprisoned… Is Academic Freedom Being Eroded? – to jailed Bahraini academic, human rights activist and writer Abduljalil al-Singace to mark his 150 days on hunger strike.

Al-Singace’s hunger strike ended on 27 January 2016 after 313 days, but he remains in prison.

In a letter accompanying the magazine, Jolley aired concerns that al-Singace – who had been protesting prison conditions while being held in solitary confinement – had suffered torture and called on the Bahraini authorities to ensure he “had access to the medical treatment he urgently requires”.

Index magazine editor Rachael Jolley pens letter to Bahrain’s Ministry of Interior regarding al-Singace, 17 August 2015.

On 15 March 2011 Bahrain’s king brought in a three-month state of emergency, which included the through establishing of military courts known as National Safety Courts. The aim of the decree was to quell a series of demonstrations that began following a deadly night raid on 17 February 2011 against protesters at the Pearl Roundabout in Manama, when four people were killed and around 300 injured.

Over 300 individuals were subsequently convicted through National Safety Courts, often for speaking out against the government or exercising their right to assemble freely. Many were punished simply for supporting or being part of the country’s opposition movement.

On a midnight raid at his home on 17 March 2011, al-Singace was arrested at gunpoint. During the arrest, he was beaten, verbally abused and his family threatened with rape. Disabled since his youth, al-Singace was forced to stand without his crutches for long periods of time during his arrest. Masked men also kicked him until he collapsed. The Bahraini authorities placed him in solitary confinement for two months. During this time the guards starved him, beat him and sexually abused him.

Al-Singace is part of what is known as the Bahrain 13, a group of peaceful activists and human rights defenders imprisoned in Bahrain in connection with their role in the February 2011 protests.

On 22 June 2011 a military court sentenced all members of the Bahrain 13 to between five years and life in prison, on trumped-up charges of attempting to overthrow the regime, “broadcasting false news and rumours” and “inciting demonstrations”.

Evidence used against them was extracted under torture, but this didn’t prevent their sentences being upheld on appeal in September 2011, at a civilian court in May 2012 and in January 2013 at the Court of Cassation. The Bahrain 13 has now exhausted all domestic remedies and are currently serving their sentences Jau prison, notorious for torture and ill treatment.

During their arrest and detention, the Bahrain 13 were subject to beatings, torture, sexual abuse and threats of violence and rape towards themselves and members of their family by police and prison authorities. Eleven of the 13 remain in prison.

The group consists of:

Al-Singace

Sheikh Abduljalil al-Muqdad, a religious cleric and a co-founder of the al-Wafaa Political Society. During his detention he has been beaten, tortured and told his wife would be raped.

Abdulhadi al-Khawaja, a human rights activist and co-founder of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights. On 8 February 2012, he began a hunger strike to protest his wrongful detention and treatment in prison. He ended his hunger strike after 110 days on 30 May 2012. He went on hunger strike again in April 2015 to protest against the torture of prisoners at Jau.

Salah al-Khawaja, a prominent human rights activist, marriage consultant and the brother of Abdulhadi. The government previously arrested Salah in the 1980’s and 1990’s for engaging in political activity against the government. He was released on 19 March 2016.

Abdulhadi al-Makhdour, a religious cleric and political activist. Authorities prevented him from showering and performing his daily prayers. They spat in his mouth and forced him to swallow. They also denied him access to a lawyer and barred him from contacting his family.

Mohammed Habib al-Muqdad, a religious cleric and the president of the al-Zahraa Society for Orphans. During his time in prison he was sexually assaulted with sticks and forced to gargle his own urine. Security guards also electrocuted him on his body and genitals.

Mohammed Ali Ismael, a prominent political activist in Bahrain. During his imprisonment, he has been beaten and verbally abused.

Abdulwahab Hussain, a life-long political activist and leader of the Al Wafaa political opposition society. He was previously detained for six months in 1995 and for five years between 1996 and 2001. He was diagnosed with multiple peripheral polyradiculoneuropathy, a condition which affects the body’s nerves, in 2005 and suffers from sickle-cell disease and chronic anaemia. His health conditions have worsened as a direct result of the torture and ill-treatment, while medicine and treatment have been denied to him. During his current sentence he has contracted numerous infections.

Mohammed Hassan Jawad, human rights activist who campaigns for the rights of detainees and prisoners who has been jailed a number of times since the 1980s. During his current imprisonment, he was electrocuted and beaten with a hose.

Sheikh Mirza al-Mahroos, a religious cleric, a social worker, and the vice-president of the al-Zahraa Society for Orphans. During his time in prison, Al-Mahroos has been denied medical treatment for severe pain in his legs and stomach. Despite having the proper documentation, he was not permitted to visit his sick wife, who later died in early 2014.

Hassan Mushaima, a political activist and leader of the Al Haq opposition society in Bahrain who has been arrested several times for his pro-democratic activities. He was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2010, which he was successfully treating at the time of his arrest. Medical results have been denied to him in prison.

Sheikh Saeed al-Noori, a religious cleric and member of the al-Wafaa Political Society. During his detention he has been tortured, forced to stand for long periods of time and had shoes stuffed in his mouth.

Ebrahim Sharif, the former president of the National Democratic Action Society. He is a political activist and has campaigned for democratic reform and equal rights. On 19 June 2015, Sharif was released following a royal pardon, only to be rearrested on 12 July 2015. He was charged with “inciting hatred against the regime” for a speech he delivered in commemoration of 16-year-old Hussam al-Haddad, who was shot and killed by police forces in 2012. He was released again in July 2016 and remains out of prison but the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy he is at risk of being arrested again because of an appeal by prosecutors.

Source: The Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy.

Also read:

– Bahrain continues to use arbitrary detention as a weapon to silence critics

– Bahrain: critics and dissidents still face twin threat of statelessness and deportation

28 Apr 2016 | Bahrain, Middle East and North Africa, mobile, News and features

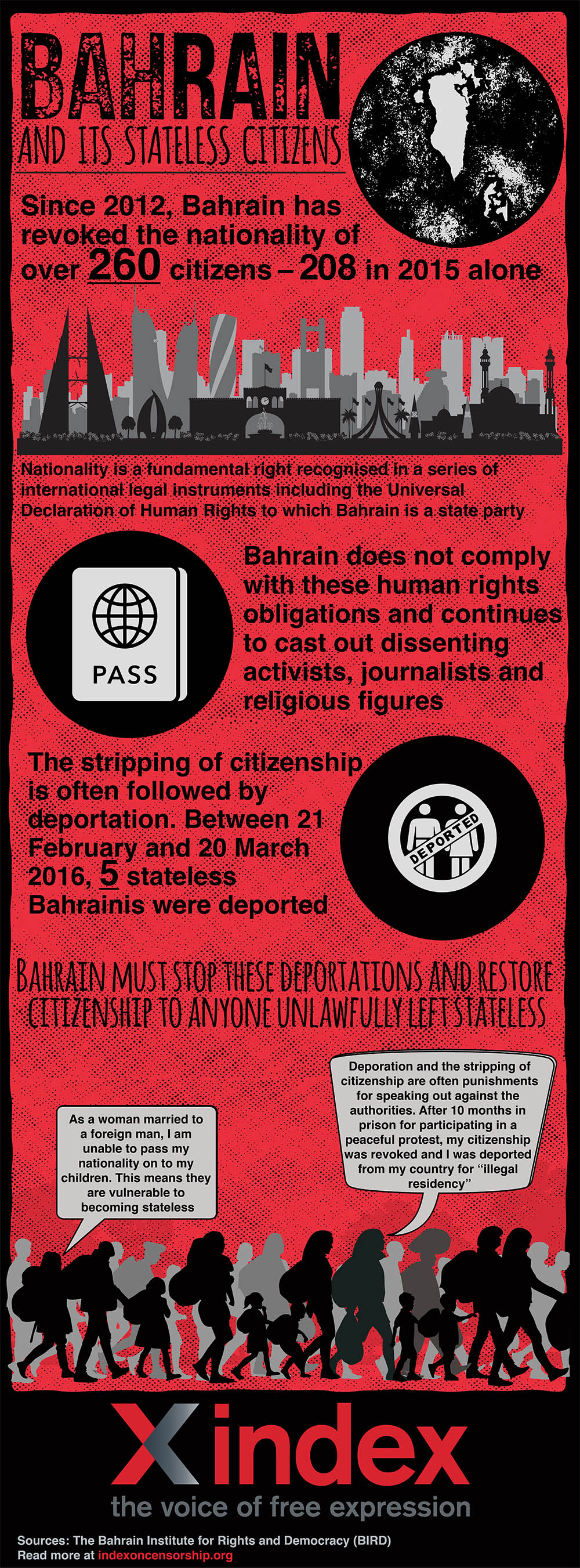

When we read about displaced people in the press, we usually hear about Syrian refugees fleeing IS or the one person per second displaced by natural disasters. We are less likely to be made aware of those who have become stateless through forced displacement.

Nationality is something most of us take for granted, but for the 10 million people worldwide who are effectively stateless, the issue is much less trivial.

Bahrain, in particular, has intensified the use of stripping citizenship from those who dissent or speak out in protest as a form of punishment. Since 2012 – when the country’s minister of the interior made 31 political activists stateless, many of whom were living in exile – 260 citizens have fallen victim, 208 in 2015 alone. Eleven juveniles, at least two of which have received life sentences, and 30 students are known to be among them.

Nationality is a fundamental right recognised in a series of international legal instruments, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights to which Bahrain is a signatory. The country repeatedly fails to comply with these obligations.

In 2014, new amendments to the country’s 1963 citizenship law further increased the power of the ministry of the interior and gave judges the authority to make anyone convicted under Bahrain’s anti-terrorism act, which fails to properly define terrorism, stateless.

In the case of Sayed Alwadaei, director of advocacy at the Bahraini Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD) and 71 others who were deprived of citizenship in January 2015, their “crimes” included vague terms such as “inciting and advocating regime change” to “defaming brotherly countries”.

Speaking to Index on Censorship, Alwadaei said: “Bahrain is setting up a dangerous precedent. No state has rendered as many of its citizens stateless in 2015. These revocations are politically motivated, and are becoming more common because they got away with it in 2012.”

“I was targeted because of my activism, and Bahrain considers human rights advocates as terrorists,” he added. “As I was not inside the country to face imprisonment, my nationality was the only way they could inflict pain on me. It was used as a tool to cause the maximum damage to stop my human rights work.”

While Alwadaei has not let the authorities take his identity, it does mean he is now stateless. “For my family, it means my infant son can’t have Bahraini citizenship, although his mother is also Bahraini.”

The danger for those made stateless inside Bahrain’s borders is that they do not have access to jobs, schools or health care and their bank accounts are closed, Alwadaei explains. “The people revoked of citizenship are at high risk of deportation by the court; many already have been under charges of ‘illegal residency’.”

These instances are also increasing. Between 21 February and 20 March 2016, five stateless Bahrainis were deported. One of these was Hussain Khairallah, whose citizenship had been revoked since 2012. He had been a union organiser and one of the medics who treated wounded protesters during the Bahrain’s Bloody Thursday in February 2011 when security forces launched a pre-dawn raid to clear a protest camp at Pearl Roundabout in Manama.

Anyone speaking out against the authorities faces such risks.

These practices and threats should immediately cease and all those who have fallen victim should have their citizenship restored. It is their right.

19 Sep 2014 | Bahrain, Digital Freedom, News and features

Maryam al Khawaja has been released

Political activist Maryam Alkhawaja has been released from prison but the charges against her still stand.

Alkhawaja was arrested at the end of last month when she travelled to Bahrain to visit her father, prominent human rights defender and co-founder of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights (BCHR), Abdulhadi Alkhawaja, who has now been on hunger strike for almost four weeks.

Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, head of advocacy at Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (Bird), told Index on Censorship he felt Maryam Alkhawaja’s release was a clear example of how international advocacy can be a success. However, he said they are still concerned about her: “We are kind of really getting mixed messages whether her release is just to ease the international pressure,” he added.

A guarantee of a residing address, and a travel ban were the conditions of Alkhawaja’s release. She is also due in court at the beginning of next month, to face charges of assaulting a police officer, which she denies.

Khalid Ibrahim, the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR) co-director, said: “We call on the government of Bahrain to immediately drop the charges and free her without conditions.”

This week BCHR and GCHR wrote an open letter to Abdulhadi Alkhawaja urging him to end his hunger strike as his life is at serious risk due to prolonged starvation. He also undertook a hunger strike in 2012 which lasted for 110 days.

Abdulhadi Alkhawaja responded from prison yesterday. Thanking his friends for their concern, he added: “But as the world can see we’re in a situation where our only choice to demand rights and freedoms is by risking our lives.”

Ibrahim added, “Abdulhadi should also be freed, along with other wrongfully detained human rights defenders who have been targeted as a result of their peaceful and legitimate activities in defence of human rights.”

Yesterday, Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB) and Bird, along with co-sponsors from several NGOs, hosted an event at the 27th session of the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, entitled Tracking Bahrain’s UPR (Universal Periodic Review) Inaction Through 2014.

The discussion was moderated by prominent human rights activist and president of the BCHR, Nabeel Rajab. Speakers at the event were Philippe Dam (Human Rights Watch), Said Haddadi (Amnesty International), James Suzano (ADHRB), Abdulnabi al Ekri (Bahrain Human Rights Organisation – BHRO) and Nidal al Salman (BCHR).

Alwadaei said the event received good coverage, and it was very beneficial for political prisoners in Bahrain. “It was a place where they would hear their voice, where they will basically believe that they are not on their own in this struggle, there is an international community monitoring so they are not isolated,” he told Index.

Also this week, women’s rights defender Ghada Jamsheer was arrested and detained on charges of defamation on Twitter. GCHR and BCHR say her online blog has been blocked in Bahrain since 2009, and they believe these recent charges to be a direct violation of her human rights.

This article was posted on 19 September 2014 at indexoncensorship.org