23 Dec 2013 | Volume 42.04 Winter 2013

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is and article by Samira Ahmed on how 15 years of multiculturalism and how some people’s ideas of it are getting in the way of freedom of expression from the winter 2013 issue. This article is a great starting point for those planning to attend the Faith and education: an uneasy partnership session at the festival.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

In 1999, the neo-Nazi militant David Copeland planted three nail bombs in London – in Brixton, Brick Lane and Soho – targeting black people, Bangladeshi Muslims and gays and lesbians. Three people died and scores were injured.

In response, the government awarded funds to local charities and community groups working on projects to build cohesion among the people that had been the targets of Copeland’s bloody campaign.

The intention was honorable, the impact underwhelming. According to Angela Mason, then head of Stonewall, the gay rights pressure group, the assumption was that all the people targeted by Copeland were “on the same side”. The truth as she sees it was that the government-funded projects exposed the uncomfortable reality that there were strong anti-gay prejudices among Muslim, Christian and black communities in Britain.

How realistic is it to expect a cohesive society could emerge from this kind of climate?

Today, the tensions between freedom of speech and religious belief remain acute – and they are systematically exploited by political groups of all stripes, from the English Defence League to radical Islamists who threaten to disrupt the repatriation of dead British soldiers at Wootton Bassett. The story consistently makes the headlines. The idea that there is an Islamist assault on British freedoms and values is widespread.

The Muslim campaign against Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses in 1988 was the crucial moment in all this. It forced writers and artists from an Asian or Muslim background, whether they defined themselves that way or not, to take sides. They had to declare loyalty – or otherwise – to the offended.

The results have been appalling, and not only in Britain. Most notoriously, the Somali writer and Dutch politician Ayaan Hirsi Ali had her citizenship withdrawn by the Dutch authorities just as Muslim expressions of outrage and death threats in response to her writing about Islam reached their peak.

In the UK, local authorities have been all too ready to cave in to pressure under cover of preventing community unrest, maintaining public order or resisting perceived cultural insensitivity.

Sensitivity to religious insult, too often conflated with racism, has frequently taken precedence over concern for free expression. In 2004 violent protests by Birmingham Sikhs led to the closure of Behzti, Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s play on rape and abuse of women in a Sikh temple.

But the problem is not always obvious. In September 2012, Jasvinder Sanghera, founder of Karma Nirvana, a charity campaigning against forced marriage, ran a stall at the National Union of Teachers conference, distributing posters for schools. She told the Rationalist Association: “Many teachers came to my stall and many said, ‘Well, we couldn’t put them up. It’s cultural, we wouldn’t want to offend communities and we wouldn’t get support from the headteacher.’ And that was the majority view of over 100 teachers who came to speak to me.”

Sanghera said that one teacher who did take a poster sent her photographs of it displayed on a noticeboard in his school. But “within 24 hours of him putting up the posters, the headteacher tore them all down”. The teacher was summoned to the head’s office and told: “Under no circumstances must you ever display those posters again because we don’t want to upset our Muslim parents.”

The delayed prosecution of predominantly Asian Muslim grooming gangs in Rochdale and Oxford has to be seen in the context of the long-standing local authority fear of causing offence. Women’s rights, artistic free speech, even child protection have repeatedly been downgraded in order to avoid the accusation of racism or religious insult.

It’s not as bad as it used to be, according to Peter Tatchell, whose organisation OutRage! promotes the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people and has campaigned against homophobic and misogynist comments by Islamic preachers and organisations. “Official attitudes are better in terms of defending free speech but still far from perfect,” he says. However, he adds, “Police and prosecutors still sometimes take the view that causing offence is sufficient grounds for criminal action, especially where religious and racial sensitivities are involved.”

The pressure isn’t necessarily overt but individual writers say they are struggling to work out where the lines are being drawn.

Writer Yasmeen Khan’s work ranges from making factual programmes, including documentaries for BBC Radio Four, to writing and performing comedy and drama. She says: “The pressure not to ‘offend’ has certainly increased over the past few years,” though she adds that it has probably affected writers and performers outside a particular religion more than believers.

Being seen as a religious believer can be an advantage when it comes to commissioning or applying for grants, she says. “But the downside is that you’re sometimes only viewed through that lens; you don’t want to be seen as a ‘Muslim writer’ – you just want to be a writer. It can feel like you’re being pigeon-holed by others, and that holds you back as being seen as ‘mainstream’. I’ve seen that issue itself being used for comedy – I was part of an Edinburgh show for which we wrote a sketch about an Asian writer being asked to ‘Muslim-up’ her writing.”

Luqman Ali runs the award-winning Khayaal Theatre company in Luton. It has built a strong critical reputation for its dramatic interpretation of classical Islamic literature. He dismisses the assertion that political correctness has shut down artistic freedom: “There would appear to be an entrenched institutional narrative that casts Muslims as problem people and Muslim artists as worthy only in so far as they are either prepared to lend credence to this narrativeor are self-avowedly irreligious,” he says. He contrasts what he sees as the “retrospective acceptance” of historic Islamic art and literary texts in museum collections with “very little acceptance of contemporary Muslim cultural production, especially in the performing arts”.

In 2011, the TLC channel in the US cancelled the reality TV series All American Muslim, a programme about a family in Michigan, after only one season. The cancellation followed a campaign by the Florida Family Association that was reminiscent of the UK group Christian Voice’s campaign against Jerry Springer: The Opera in 2005. Lowe’s, a national home-improvement chainstore and major advertiser, pulled out of sponsoring the show after the group claimed the series was “propaganda that riskily hides the Islamic agenda’s clear and present danger to American liberties and traditional values”.

Lowe’s denied its decision was in response to the Florida Family Association campaign. But amid the hysteria generated, including protests outside Lowe’s stores, ratings for the show plummeted. Many Americans decided not to watch it. As with Jerry Springer: The Opera, a small group had created a momentum of outrage that led to a fatal atmosphere of threat and intimidation around a piece of mainstream – and until then, highly successful – entertainment. The Bollywood thriller Madras Café was withdrawn from Cineworld and Odeon cinemas in the UK and Tamil Nadu, India, after a campaign by Tamil groups who found it “offensive”.

Veteran comedy writer John Lloyd, speaking at a British Film Institute event marking the 50th anniversary of the broadcast of the satirical news programme That Was The Week That Was in 2012, said there was now an obsession with “compliance” by tier after tier of broadcast managers, which he felt had suffocated satire. “Now,” said Lloyd, “everyone’s jibbering in fright if you do anything at all.” He contrasted the current climate to his experience working for Not The Nine O’ Clock News when, he said, he was “encouraged to provoke and challenge”.

Writer and stand-up comedian Stewart Lee, who co-wrote Jerry Springer: The Opera, is currently working on a new series of his award-winning Comedy Vehicle for BBC Two. He believes a general uncertainty about British legislation on religious offence is affecting what gets produced: “It’s all very confusing. I don’t know what I am allowed to say. There is a culture of fear generally now in broadcasting. No one knows what they are allowed to do.”

“In Edinburgh in August 2013, a (nonbroadcast) show in a tent funded by the BBC at 9.30pm saw the BBC person running it pull a song by the gay musical comedy duo Jonny and the Baptists about laws concerning gays giving blood because it ‘promoted homosexuality’. This at 9.30pm, in a country where it is not illegal to promote homosexuality, and not for broadcast.

“In series one of Comedy Vehicle, I had a bit on imagining Islamists training dogs to fly planes into buildings. This was pulled on the grounds that it appeared deliberately provocative to Muslims because of the dog taboo in Islam. I looked into this, and read a load of stuff on it. There is no dog taboo in the Muslim faith.”

A BBC spokesman said: “The band were invited to perform on our open garden stage which was run as a family friendly venue for the 24 days it was open to the public. With the possibility of children and young people in the audience, we asked the band to tailor their short set to reflect the audience. They did so, and in one of these, a late night notfor- broadcast show, their set included the song which Stewart Lee refers to. The BBC has a strong track record of offering comedians opportunities to perform their edgiest material without restraint during the festival and we will continue to do so.”

Lee described the Jerry Springer: The Opera debacle, explaining that the pressure group Christian Voice “were able to scupper the viability of the 2005-2006 tour” of the play by informing theatres they would be prosecuted under the forthcoming incitement to religious hatred bill if they staged the play. The bill was later defeated by one vote in the Commons, and soon after the House of Lords scrapped the blasphemy laws. “But,” says Lee, “I think the public perception is that both these laws still exist.”

He says he doesn’t like to make a fuss: “The BBC is beset on all sides by politically and economically interested partners who want to see it destroyed. I wouldn’t expect the BBC, any more, to go to the wall about something I wanted to say. I’d just say it somewhere else – on a long touring show for example – and get better paid for it anyway! I am also anxious not to appear to contribute to the notion that ‘political correctness has gone mad’. People say, ‘ah but you’ve never done stuff about Islam’. I have. Nothing happened. But I have not done stuff about Islam in the depth I have stuff about Christianity as it is not relevant to me in the same way.”

Lee says his writing for tours isn’t affected by the fear of offence because his solo tours are “cost-effective and largely off the radar of the anti-PC brigade or people looking for things to complain about”.

However, he says, when it comes to the television series, he does consider the power of offence. “It affects what I write,” he says. His new show addresses the Football Association’s objection to the word “nigger”. He suspects that the BBC might get cold feet about this bit. “So I will drop it and use it live and on DVD. I don’t see TV as the place to experiment with certain types of content any more.”

But he says that one of the most important things about freedom of speech is that it applies to everyone. “I don’t think a lot of the jokes that, say, Jimmy Carr and Frankie Boyle do are worth the annoyance they cause, but I would defend their right to say them.”

So what, if anything, has changed for writers and what they feel they can write about since his experience with Jerry Springer?

“It’s all much worse,” Lee says. “But for many reasons: lack of funding mainly.” In April 2013, culture secretary Maria Miller addressed members of the arts industry at the British Museum, arguing that: “When times are tough and money is tight, our focus must be on culture’s economic impact.”

But as Lee points out, “it’s harder to justify funding something worthwhile in the current climate if people are storming the publicly funded theatre, such as Behzti, in protest.” “It has lost its moral authority in many ways,” he says, adding that ratings are at the forefront of commissioners’ minds.

There have been high-profile attempts to link comedy and Islam, such as the recent Allah Made Me Funny international standup tours. The Canadian CBC sitcom Little Mosque on the Prairie defied self-styled Muslim community leaders’ complaints about insult and offence to run for six highly-rated seasons, finishing in 2012. The BBC’s own Citizen Khan, which begins its second series in 2014, has similarly ignored claims of insult. Both sitcoms combine a Muslim family setting with very familiar sitcom themes.

In Britain, the overly cautious attitude to free speech and religion supposed to create community harmony has coincided with growing fundamentalist intimidation often promoted within enclosed immigrant communities. Sikh gangs have targeted mixed weddings in temples, and there have been tense stand-offs between Sikhs and Muslims over allegations of sexual grooming in Luton and elsewhere. British Ahmadiyya Muslims, who fled persecution in Pakistan, have struggled to draw media attention to the orchestrated hate campaigns being conducted against them by some Sunni groups. We need to feel free to criticise religious groups when they cross lines and commit crimes, without worrying about the cultural upset.

As Kenan Malik has said, the refusal to confront these issues in open and frank discussion, is “transforming the landscape” of free speech. Even in the United States, where free speech is enshrined in the constitution, there are serious questions being asked about what free speech actually means – particularly when it comes to religion.

The right to free speech should never be half-hearted. People have the right to be offended, but they don’t have the right to stop others speaking, discussing and debating ideas.

16 Dec 2013 | News

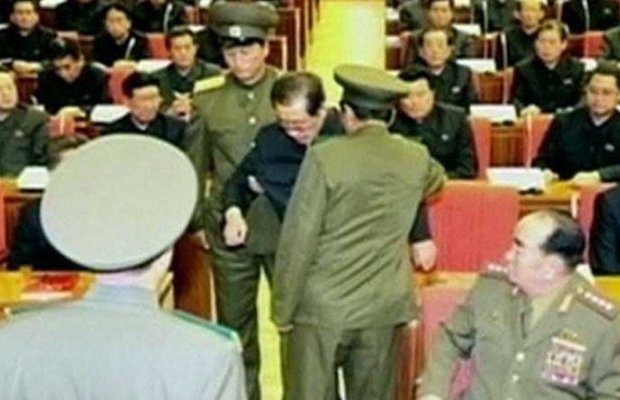

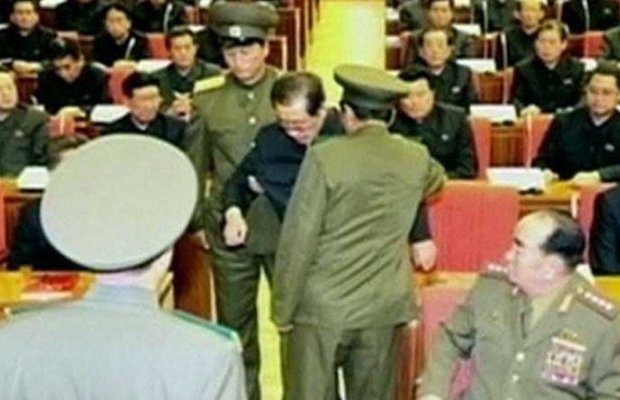

North Korea has expanded its deletion of a few hundred online articles mentioning Jang Song Thaek, the executed uncle of Kim Jong Un, to all articles on state media up to October 2013, numbering in the tens of thousands.

North Korea has expanded its deletion of a few hundred online articles mentioning Jang Song Thaek, the executed uncle of Kim Jong Un, to all articles on state media up to October 2013, numbering in the tens of thousands.

“It’s definitely the largest ‘management’ of its online archive North Korea has engaged in since it went online. No question,” Frank Feinstein, North Korea news analyst, told this writer on Sunday (15 December).

The Korean Central News Agency (www.kcna.kp), the state’s main organ, started publishing in its current online form on 1 January, 2012, and had some 39,000 Korean-language articles by mid-December 2013, with many translated into other languages. “Now however there are now no articles in the archive from prior to October 2013, with everything numbered to around 35,000 – or to October this year – gone,” said Feinstein, director of KCNA Watch, which analyses North Korean media for keywords and converts that into visual data to gauge reporting trends. Similar proportions of deletions were true for Korean Workers’ Party paper Rodong Sinmun and www.uriminzokkiri.com.

Just four days passed from the arrest Kim Jong Un’s uncle Jang, which was televised across North Korea, to his execution on 12 December 12. Thereafter the expurgation of any mention of Jang from the state news files took just hours. Following outages that to seemed affect several state online news sources, of some 550 Jang-related Korean articles on www.kcna.kp, Feinstein estimated that by late Friday, “every single one has either been altered, or deleted, without exception”. This included the most anodyne reports such as a 5 October KCNA story about Kim Jong Un visiting a hospital under construction now reads: “He personally named it ‘Okryu Children’s Hospital’ as it is situated in the area of Munsu where the clean water of the River Taedong flows.” But the original had continued: “He was accompanied by Jang Song Thaek, member of the Political Bureau of the CC, the WPK and vice-chairman of the NDC, and Pak Chun Hong, Ma Won Chun and Ho Hwan Chol, vice department directors of the CC, the WPK.”

Other examples are at the KCNA Watch site, and as also observed by North Korea watcher, Martyn Williams at www.northkoreatech.org.

What’s new about the North’s retrospective media management is its scale and that it’s doing it online, before a global audience. “This is North Korea censoring itself to the world – not just to its own citizens…Personally, I can’t believe they could think they’d get away with this sort of revisionism,” said Feinstein.

Nonetheless, the North can sustain its digital Ministry of Truth antics on the World Wide Web by preventing its output from being indexed. ‘It already works on KCNA – Google can’t index it at all. You can’t even link to an article on KCNA,’ said Feinstein, pointing to Google’s entire, paltry record of KCNA’s office in Pyongyang via this link.

It’s not clear even if South Korean intelligence or news agency Yonhap can archive KCNA’s database in its live form. “While North Korea doesn’t understand much about how to successfully operate online, they do understand this much.”

One theory contends that the North publishes different propaganda for internal and external consumption. For sure, North Korean people can only access news produced by the North Korean state, accessing www.kcna.kp through the country’s intranet, but more likely from the state TV, radio or newspapers on station platform hoardings of which obviously none enable access to digital or visual archives. TV has also been noted as adjusted, with a documentary first shown on 7 October 2013 being reshown on 7 December with Jang cut out of shots by adjusted focus and framing.

The upshot is this: “Our party, state, army and people do not know anyone except Kim Il Sung, Kim Jong Il and Kim Jong Un,” according to the sole English-language article left on KCNA that mentions Jang, a vicious 2,750-word denouncement from 13 December 13. The piece calls Jang “impudent, arrogant, reckless, rude and crafty,” “despicable human scum … worse than a dog,” who, backed by “ex convicts”, had plotted to destroy the economy before “rescuing” the country by military coup and billions earned from hoarded precious metals.

“They are serious about removing him from history,’ said Feinstein, except for passages such as “the era and history will eternally record and never forget the shuddering crimes committed by Jang Song Thaek, the enemy of the party, revolution and people and heinous traitor to the nation,” which concludes the KCNA piece. Meanwhile, “Rodong Simnun no longer knows Jang as anything other than a traitor,” tweeted Korea historian and linguist, Remco Breuker.

Traffic to www.kcna.kp has never been higher, even than for the death of Kim Jong Il, as people now follow stories to the source and are captivated by the apparent novelty of North Korea having an online presence, and one that uses such bizarre language. “Once they find KCNA, there’s no going back.” KCNA’s legitimacy as an analytical source for the North Korean state’s views is oft obscured by its saltier reportage.

Outside news sources are also sensationalist. While most Pyongyang watchers agree Jang was shot dead, Taiwanese news reported he’d been eaten by 120 dogs in front of Kim Jong Un and 300 government ministers in an hour-long death. Feinstein also pointed to a globally syndicated article before Jang’s trial that precipitously claimed www.kcna.kp had cleared out all Jang articles, when in fact articles mentioning Jang were still up. Basically, KCNA “has a bad search function”, said Feinstein.

While the case provides a tantalising view of what the Soviets might have done in the Internet age, it has also pushed out of the headlines another North Korea story, the release of American tourist Merrill Newman who had been held in North Korea since October on charges of “espionage” relating to his military service in Korea during the 1950-1953 war. Newman, who had gone to North Korea as a tourist, said he had not understood quite how far the North Korean state does not consider the war to be over – something arguably partly attributable to the US media barely ever mentioning the conflict, despite the country still being not at peace with North Korea.

Ironically, KCNA Watch has been blocked in South Korea since 25 October. Visitors to the site hit a Korea Communications Standards Commission (KSCS) blocking screen that says “connection to this website you tried to access is blocked as it provides illegal/hazardous information,” under the 1948 National Security Act, which restricts anti-state acts or material that endanger national security, including all printed and online matter from Pyongyang. Civilians seeking to analyse KCNA material in South Korea need official clearance, with the data viewed under armed guard and deleted immediately afterwards, said Feinstein. The block extends to foreign embassies in Seoul and is under increasing criticism as a blanket weapon for stifling dissent. In August the UN special rapporteur on human rights Margaret Sekaggya called it “seriously problematic for the exercise of freedom of expression”.

Sybil Jones

9 Dec 2013 | Volume 42.04 Winter 2013

The upcoming winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine includes a special report on religion and tolerance, with articles from around the world.

The upcoming winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine includes a special report on religion and tolerance, with articles from around the world.

Writers include the Bishop of Bradford, Salil Tripathi, Samira Ahmed and Kaya Genc. There’s an interview with Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti ahead of the opening of her new play, and 10 years after Behzti; while cartoonist Martin Rowson writes and draws about how comedy and religious offence come into conflict. Natasha Joseph writes from South Africa on why some portraits of President Zuma made him see red. Alexander Verkhovsky discusses the new blasphemy law in Russia, and former BBC mobile editor Jason DaPonte discusses why computer games are not all bad.

As part of the special report, writer Brian Pellot goes online with the Mormons to see how they use technology to talk to the unconverted, and asks if online chats will replace missions. Germans have been outraged by the revelations about US and UK surveillance, now they have plans to do something different to put a stop to snooping in the future, Sally Gimson reports. From Brazil, Ronaldo Pelli looks at the reaction to people practising religions of African origin, and investigative writer and author of Fast Food Nation Eric Schlosser talks about the threats to investigative journalism now and in the future.

Also in this issue:

Padraig Reidy on flags, controversy and Northern Ireland

Xiao Shu on the Chinese crackdown on the New Citizens’ Movement

Kaya Genc on the rise of a new type of media in Turkey

22 Nov 2013 | News, Russia

This autumn the Russian authorities have made it clear that they are intent on extending the blocking of websites. In September, two prominent State Duma members of the ruling United Russia party, Robert Shlegel and Maria Maksakova, submitted amendments to an anti-piracy law, prohibiting illegal distribution of movie. These entered into force on 1 August. The deputies propose to supplement the law with measures that protect the copyright of musicians, writers and computer program developers.

In November, Andrei Lugovoi, a MP from the rightwing nationalist Liberal Democratic Party, submitted a bill proposing the extrajudicial blocking of sites containing calls for riots or extremist activities, including calls to take part in public events held deemed to be in violation of the established order. Hitherto, such sites have been subject to blocking by a court order. This initiative was met with general approval by members of the State Duma.

Extremism

Chechen prosecutor seeks to block anti-Putin article

On 23 September the Chechen Republic prosecutor announced the filing of writs against internet service providers (ISPs), demanding restrictions on access to a website publishing the anti-Putin polemic “Putin’s plan is Russia’s misfortune”. The article is on the Federal List of Extremist Materials.

Chechen prosecutor moves against ISPs over Islamist material

On 11 September the Chechen Republic prosecutor announced the filing of writs to restrict access to a website featuring the Islamist piece “Zaiavlenie komandovaniia mudzhakhidov Vilaiata Galgaiche” (Statement of the Mujahideen commanders of Vilayata Galgaiche), which is on the Federal List of Extremist Materials. The defendants were not identified in the report.

Smolensk prosecutor starts proceedings against ISP for video

On 11 September it was reported the Leninsky district prosecutor had issued a writ to the ISP MAN Set for allowing public access to videos included on the Federal List of Extremist Materials. The ISP complied with the writ and those responsible for allowing access faced disciplinary charges.

MTS receives a order to block video in Altai Republic

On 10 September the Gorno-Altaysk city court granted the Altai Republic prosecutor’s motion demanding that the ISP Mobilnye Telesystemy restrict access “to an extremist video clip posted on 16 websites”. The clip in question was not specified. The decision was made in the absence of the defendant.

Moscow court orders ISPs to block sites

On 25 September the Moscow city prosecutor reported that the Kuzminsky district court had accepted the demand of the Kuzminskaia interdistrict prosecutor that the ISPs Click and Obiedinennye Lokalnye Seti limit access to five websites that made available Hitler’s Mein Kampf. The prosecutor also demanded a block on a website containing citizens’ personal data.

Krasnodar moves against extremist posts on social network

On 25 September the Krasnodar regional prosecutor reported that the Adlersky district court in Sochi had accepted the demand of the district prosecutor that it define two Islamist texts published on the VKontakte social network as extremist.

Prosecutors move against website in Chechnya

On 11 September the Urus-Martanovsky district prosecutor filed a lawsuit demanding that ISPs limit access to a website for publishing the video Videovestnik Russkoi Molodezhi (the Youth Messenger), included on the Federal List of Extremist Materials. The case is pending.

Blogs targeted in Ulyanovsk

On 25 September the Ulyanovsk regional prosecutor reported that the Zavolzhsky district prosecutor had issued writs demanding the ISPs ER-Telecom Holding and Rostelecom cease offering access to the websites kcblog.info and t-kungurova.livejournal.com. Both are legally recognised as extremist [for being aliases] for the Chechen militants’ website Kavkazcenter.

Education and schools

Kamchatka schools told to shield students

On 13 September it was reported that the Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky city prosecutor had issued demands that several schools install content filters to prevent access to websites containing extremist propaganda.

Lipetsk schools allowed access to banned sites

On 27 September it was reported that the Dankovskaia interdistrict prosecutor in Lipetsk region had demanded the director of Dankov Secondary School No 1 eliminate violations of the child protection law. An inspection had revealed that the internet filtering system installed on school computers was not blocking access to websites about drugs, pornography and suicide. It also allowed access to the texts of songs included in the Federal List of Extremist Materials.

Blind students ‘could read Mein Kampf’ in Omsk school

On 17 September it was reported that the Omsk city prosecutor had identified a number of violations at Boarding School No 14 for visually impaired children. In particular, the school computers allowed access to Hitler’s Mein Kampf, included on the Federal List of Extremist Materials, as well as to websites containing pornographic images, violence and drug propaganda.

University fined for banned site breach

On 3 September it was reported that the Sverdlovsk regional arbitration court had accepted the demand of a fine for B N Yeltsin Ural Federal University, issued by the Ural regional office of the watchdog Roskomnadzor. The university had failed to submit an application for an access code to the register of banned websites. As a result, students had access to resources included on the register. The court imposed a fine of 30 thousand rubles on the university. The court’s decision has not yet entered into force.

Suicide propaganda

Penza prosecutor tries to block suicide prevention

On 11th September it became known that the local Penza’s prosecutor office asked the court to block access to the website Pobedish.ru (“You win”). The website is part of Perezhit.ru group – a suicide prevention resource that works with psychologists, psychiatrists, forensic experts and the clergy.

Kaliningrad prosecutor moves against suicide sites

On 23 September it was reported that the Moskovsky district court of Kaliningrad had received a prosecutorial request that the ISP TIS-Dialo restrict access to several websites describing methods of committing suicide.

Drugs and alcohol

Facebook almost blocked for advertising smoking blends

The Russian branch of Facebook came close to being blocked for publishing advertisements for illegal smoking blends in September, according to reports from the Itar-Tass news agency, citing Facebook’s Russian press service. Facebook said users had reported the ads for smoking blends on 16 September and the company had been unable to do so because of a technical glitch. The incident followed a warning from the Federal Antimonopoly Service (FAS) that it intended to inspect social networking sites for ads for banned substances. The media watchdog Roskomnadzor subsequently warned Facebook that it had been provisionally placed on the register of banned websites and would be shut down if it did not remove the ads. Facebook announced on 19 September that it removed the offending content.

Reports filed on ISPs in Kurgan

On 18 September it was reported that the Kurgan regional office of Roscomnadzor had compiled reports on two ISPs that were not blocking access to websites advertising illegal drugs.

Yekaterinburg complains about alcohol advertising

On 17 September it was reported that Sergei Trushin, deputy head of the Yekaterinburg administration, had sent a letter to the regional office of the interior ministry requesting action against websites advertising the sale of alcohol. The Ministry of Internal Affairs shut down the sites and the people behind them were fined.

Gambling and casinos

Yekaterinburg ISP loses appeal

On 3 September it became known that the Sverdlovsk regional court had accepted the demand of the Kirovsky district prosecutor in Yekaterinburg that the ISP VympelCom-Communications block five gambling websites based on foreign servers. The demand had been accepted by a district court but the ISP had appealed.

Eight gambling sites blocked in Tomsk

On 12 September the Tomsk regional prosecutor announced that the Strezhevoy town prosecutor had filed a lawsuit against the ISP Danzer demanding restrictions on access to eight online casinos. The ISP complied by blocking the sites.

Rostelecom blocks William Hill

On 5 September Rostelecom blocked its subscribers’ access to the largest UK betting website, williamhill.com. The ISP Qwerty in Moscow and the surrounding region also blocked access to the site.

Rostelecom subscribers could not access the website’s primary domain, online casinos or online poker sites. Instead, they saw a message announcing that the domain had been blocked by court order or that the address had been placed on the register of banned websites.

Torrents and piracy

Moscow court bans 11 torrent sites

On 5 September Moscow city court accepted the claim of NTV-Profit against 11 online torrent sites — free-torrents.org, inetkino.org, rejtinga.net, nnm-club.me, hotbase.org, x-torrents.org, goldenshara.com, rutor.org, torrnado.ru, torrent-shara.org, nntt.org – that were distributing the popular Russian-made films Vor (The Thief), Krutoi Povorot (Sharp Turn) and Interny (The Interns).

Portal avoids block for streaming

On 5 September Moscow city court accepted a request by the Central Partnership Sales House requesting to block the torrent portal Rutracker.org to prevent it distributing the American films Now You See Me and Taken 2. Rutracker removed the films and avoided being blocked.

And the rest

Pussy Riot icon banned

On 9 September it was announced that the Tsentralny district court had granted a request by the Zheleznodorozhny district prosecutor of Novosibirsk to declare an icon-like image of Pussy Riot, created by the artist Artyom Loskutov, banned from distribution via the internet. The image has been added to the register of banned websites.

Block on inaccessible site demanded

On 24 September it was announced that the Yegoryevsk city court had granted the city prosecutor’s motion against Yegoryevskaia Telekommunikatsionnaia Kompaniia (Yegoryevsk Telecommunications Company) to limit access to an online casino website. Earlier, the same court had ruled in favour of the provider, but the prosecutors challenged the decision, and the Moscow regional court sent the case back for retrial. The Yegoryevsk city court ordered the provider to restrict access to the site, but the access to the website was found to already be blocked – perhaps, by the online casino’s owner or another operator. However, the court insists that Yegoryevskaia Telekommunikatsionnaia Kompaniia should be the one to implement access restrictions. The court provided no advice on how to block an already inaccessible site.

Stavropol prosecutor seeks block on e-library for one book

On 25 September the Stavropol regional prosecutor reported that the Novoaleksandrovsky district prosecutor had filed a claim in Leninsky district court against the Stavropol regional branch of Rostelecom, demanding restrictions on access to the website royallib.ru. The site provides public access to the book Skiny: Rus probuzhdaetsya (Skinheads: Rus Is Awakening) by Dimitri Nesterov, which is on the Federal List of Extremist Materials

Roscomnadzor blocks porn site

On 13 September it was reported that Roscomnadzor had included the porn site redtube.com on the register of banned websites. The reason for placing the site on the register was not specified, but it might have been because it published a cartoon entitled “Hentai school girls fucking for better grades”.

TV channel targeted in Moscow

On 6 September it was announced that the central investigations directorate of the ministry of internal affairs in the Moscow Region had demanded that the website of Dozhd (Rain) TV channel be blocked for violation of Part 2 of the Criminal Code Article 282 (“incitement to hatred or hostility and humiliation of human dignity”). TV Dozhd is the country’s most popular online TV news channel and is relatively independent. The exact nature of the material deemed objectionable was not reported. The Ru-Center domain registrar confirmed the existence of the police request, but, since the request was filled out incorrectly, the TV channel website was not blocked. Interior ministry representatives subsequently denied the reports. The administration of Dozhd also stated that they had received no such orders from the ministry of internal affairs.

Saratov ISP ordered to ban ads for bankrupt company

On 6 September it was reported that the Kirovsky district prosecutor in Saratov had filed a lawsuit against the ISP Saratovskaia Sistema Sotovoi Sviazi (SSSS) demanding that it restrict access to an internet portal advertising a bankrupt company. The ISP refused to block the relevant IP address because it was also used by three unrelated sites. In addition, the provider stated that it had no control over IP address changes, while an advertiser could always change it. However, the court granted the prosecutor’s claim and ordered the ISP to restrict access to the site.

ISPs fined in Moscow and Saratov

On 3 September it was announced that the Moscow arbitration court had fined the ISP KMC Telecom and that the Saratov regional arbitration court had fined the ISP Hemikomp for ignoring the requirement to sign up to the register of banned websites. In both cases, the decisions were made based on evidence from the media watchdog Roskomnadzor. It said the ISPs’ reluctance to register and block access to websites listed on the register was in violation of Part 3.14 of the Administrative Code (entrepreneurial activity without state registration).

Amur ISPs reported for non-compliance

On 14 September it was reported that the Amur office of Roscomnadzor had filed administrative responsibility reports against the following ISPs: Amurtelekom, A- Link, Transsvyaztelekom, Inter.kom, KRUG, GudNet, Moia Komputernaia Set, Gorodok, and Edinaia Gorodskaia Set. Roscomnadzor demanded penalties for their failure to comply with the register of banned websites. If the violation is not addressed, each provider faces a fine of up to 40,000 rubles.

Consumer protection site temporarily blocked

On 26 September it was reported that www.i-zpp.ru, a consumers’ rights website, had been added to the register of banned websites. The addition was triggered by the decision of the Salekhard city court of 18 April 2013 to block access to websites containing extremist materials. The consumer protection website had been blocked because it had the same the IP- address as extremist websites. In late September the site was, once again, accessible from Moscow.

Owner loses appeal against ban

On 20 September it became known that Vladimir Kharitonov, the owner and administrator of the website Novosti elektronnogo knigoizdaniia (News of electronic book publishing, digital-books.ru), had filed an appeal with the Moscow city court against Roskomnadzor’s decision to include it on the register of banned websites. Kharitonov had previously attempted to appeal the decision, but the Tagansky district court dismissed his appeal in March. The Moscow city court did the same in September. The owner of the website intends to appeal to the European Court of Human Rights.

Prosecutor blocks 15 Omsk sites

On 17 September it became known that the Omsk city prosecutor had succeeded in blocking 15 websites. Previously, the Tsentralny district court had dismissed the claim of the Omsk city prosecutor demanding that the local branch of Rostelecom restrict access to 15 sites selling certificates and diplomas. The prosecutor appealed the decision and the Omsk regional court overturned the lower court’s decision and ordered the internet provider to block the websites.

This article was originally posted on 22 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

North Korea has expanded its deletion of a few hundred online articles mentioning Jang Song Thaek, the executed uncle of Kim Jong Un, to all articles on state media up to October 2013, numbering in the tens of thousands.

North Korea has expanded its deletion of a few hundred online articles mentioning Jang Song Thaek, the executed uncle of Kim Jong Un, to all articles on state media up to October 2013, numbering in the tens of thousands. The upcoming winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine includes a special report on religion and tolerance, with articles from around the world.

The upcoming winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine includes a special report on religion and tolerance, with articles from around the world.