Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

(Photo: Courtesy Boniface Mwangi)

Boniface Mwangi is an award winning Kenyan photographer and activist. During the 2007 post-election skirmishes he took thousands of photos. His coverage of those attacks entailed great danger as, more often than not, he had to falsify his ethnic identity. In 2009 he founded Picha Mtaani, the first-ever street exhibition in Kenya which was held in towns across the country, showcasing the post election violence photographs to a wider audience beyond Nairobi.

Mwangi has been recognized as a Magnum Photography Fellow, Acumen Fund East Africa Fellow, TED Fellow, and twice as the CNN Multichoice Africa Photojournalist of the Year, among other awards. He currently runs Pawa 254, a collaborative hub for creatives in Kenya. Mwangi recently received the Prince Claus Award 2012 and is now a senior TED fellow.

Mwangi was interviewed by Index on Censorship Head of Arts Julia Farrington at an arts event in Ethiopia in July.

Index: How would you describe Kenyan government’s position on freedom of expression?

Mwangi: Recently the president and deputy president had a media breakfast and invited all the top editors and bloggers, writers at the state house to a meeting. This is unheard of, it has never happened before. The new government is being advised by a British firm advising – it was actually the same firm that advised the US government on how to deal with insurgency in Afghanistan. They are a very smart PR company, they know how to package lies and make it look like the truth, they know how to package crap and sell it to the electorate. At the moment there is a communication bill that is going through parliament which goes against freedom of speech and when they met, the media said they want self-regulation, they don’t want to be regulated by the state.

But beyond this censorship in Kenya is by choice – it is because of the owner’s business interest; they don’t upset the system because they are going to lose business, lose money. The biggest advertisers in the country are the government and the bigger corporations. Editors know as long as they go on the path of truth, they won’t sell advertising space. They spend so much money on advertising – so it is more self-censorship than anything else.

Kenyan journalists are poorly paid. They are paid by story and the money is very little which makes them easy to be bribed, corruptible. If you work in the rural area you have no transport and to get around you rely on the local police to give you a ride or the local politician or drug lord and you get compromised in the process. I worked for five years I know how it works there is a lot of brown envelopes exchanging hands, depending on who is who. And sadly no-one talks about corruption in the media.

Index: You are saying media is compromised but it is essentially independent?

Mwangi: It is independent – there is very little government interference. It’s almost non-existent – they know the media is controlled by interest. Not a single journalist is in jail at the moment. In the previous government there were a lot of libel suits that were awarded to politicians, actually a ridiculous amount of money was involved, but that has stopped.

The other thing is the emergence of bloggers and citizen journalists who can write about anything, which is actually a good and a bad thing because they can write about rumours and attack people’s lives. But sometimes they can become an alternative channel for communication. I have seen a lot of stories that have not made it into the mainstream media, but if you go on line or if you buy the tabloids, it may be exaggerated but there may be some truth in it.

Index: How would you describe the Kenyan’s people’s appetite for freedom of expression?

Mwangi: Kenyan people do not want to fight for their freedoms, they want activists to do it for them, so it is only a minority who are fighting for these rights. There is this wait and see approach on these issues, and it hurts the whole country. Kenyans have all grown up with parents who told them, don’t protest you are going to get arrested, and that fear has been carried out to this generation. There is the lock in the mind of Kenyan people that says we can’t do this, it isn’t possible it is too scary, too daring and dangerous to do it. If you don’t overcome that fear it is going to be passed on to my kids and my kids’ kids so that is what we are trying to do, to give people courage. Our acts of courage are trying to get the people to protest and resist injustices with confidence that nothing bad will happen to them.

Index: You believe doing very extreme, provocative actions is the right way?

Mwangi: We are always going for the shock effect. The shock effect says that if they can do that then other people can do some smaller than that. It has an influence – if I can do it you can do it.

Index: You don’t think it alienates? People could say those guys are crazy?

Mwangi: I don’t think many people think we are crazy – maybe some upper class people and some politicians. But the people understand where we are coming from and they understand our anger and given the chance they would also do extreme things, but they are actually afraid.

Index: Do you think that part of what you need to do is to test the boundaries of the law especially in the context of the new constitution?

Mwangi: We need to do that for Kenyans because we have some over-zealous police officers who arrest and charging people using non-existent laws . So it is important that people understand their rights. And the police should be educated on the bill of rights so that they don’t infringe on Kenyan’s rights.

Index: Some say freedom is a luxury, let’s get people housed and educated first and then let’s turn our minds to freedom of expression. What do you think?

Mwangi: Education is a term that is used very loosely. Many Kenyans are very full of wisdom and they have never been to school. So when you are talking about education you are talking about western standards of how people get educated – more education in what they call the ‘good life’ that isn’t going to change anything.

Freedom is good – it gives human beings dignity, with freedom you can do what you want – it means you can challenge authority, you can give feedback to the government about how you feel. So if you look at a dictatorship most of them stagnate because there is only one thinker amongst a population of many people. That one thinker cannot be omnipresent then you find that there is a shortage of ideas and a want of thinking. So freedom of expression is key to life and to democracy. It has to be there at the start – it is like life.

Index: This space which you have created – is it for a planning space for activists? Or it’s a public space? Or it’s both.

Mwangi: It is a space for creatives where we people share plan events, protest, a place where people discuss. So it’s a place where you can come in any time and discuss, read a book, come in anytime and do a grafitti or just chill or read a book. It’s called PAWA 254. Creatives, activists, journalists and film-makers, guys and women who are like minded who have a real job or a real career but they want a place where they can come and meet like-minded people and discuss.

It is open every day, we plan for it to be open 24 hours per day. And the debate nights are every Tuesday and other days we have different activities where we train activists, photographers, animators or cartoonists – different trainings going on at any given time.

Index: The authorities know you are there. Do they let you get on with it?

Mwangi: The thing is we have a very progressive constitution if you come to my property they need to have a search warrant or a warrant for my arrest. They can’t just come and ask questions. They have to read me my rights. That is actually something that doesn’t happen in this continent but Kenya has a very progressive constitution, which if everything was working could make it a beacon of democracy and human rights.

A demonstrator disguises her face during a the “March of the Sluts” in Rio de Janeiro. (Photo: Vito Di Stefano / Demotix)

“If someone is gay, and seeks God’s good will, who am I to judge?”, he told reporters on his flight back to Italy on 28 July.

“The problem is not having this orientation. We should be brothers. The problem is lobbying towards this orientation, or lobbying for jealous people, politicians, masons. This is the worst problem,” Francis said.

Frei Betto, one of Brazil’s most prominent members of Liberation Theology – a leftist religious trend created in South America in the 70’s – hopes that the Pope’s remarks about the gay community can start a new phase of dialogue.

“With Francis, the themes of sexuality could be discussed in the church with greater freedom and integrity,” he said in an interview.

However, Francis could not escape criticism from leaders of Brazil’s gay movements.

“During the debate on equal marriage law in Argentina, (Jorge Mario) Bergoglio acted as an extremist leader. He said the bill was a plot of the devil to destroy God’s plan and called for holy war”, says deputy Jean Wyllys, recalling the attitude of the pontiff back in 2010, when he was archbishop of Buenos Aires.

“Pope Francis is even worse that pastor Feliciano, because he is much more powerful, richer and smarter”, says Bahia’s Gay Group president Luiz Mott, in a reference to federal deputy and pastor Marco Feliciano, president of the Chamber of Deputies’ Human Rights Committee and famous for his homophobic remarks.

“(Francis) began his pontificate with two deeply antigay attitudes: he canonized Pope John Paul II, the biggest homophobe in the 20th century, and signed along with Pope Benedict XVI his first encyclical, which condemns gay families.”

Frei Betto concedes that most Catholics still feel cautious about more controversial issues like gay marriage, but he believes that the pope “opened an important door” to gay people.

“He took the theme out of the closet. He also supported the demonstrations, emphasizing that young people should protest, and criticized the idolatry of power and money.”

The pope spoke about the demonstrations that have broken out in Brazil’s major cities since early June. Addressing cultural and business leaders at Rio de Janeiro’s Municipal Theater, Francis said that constructive dialogue is “essential to face the present,” in a clear mention to the protests.

“Between selfish indifference and violent protest, there is an option whenever possible: dialogue. Dialogue between generations, the dialogue with the people, the ability to give and receive, remaining open to the truth,” Francis said.

Later, speaking to 3 million people on Copacabana beach, he expressly urged people to go on protests, saying that those who want to be “protagonists of change” should “overcome apathy”, though in an orderly way. “Go out the streets!”, Francis exclaimed to the crowd.

However, while the Pontiff spoke, a few hundred protesters gathered in the “March of the Sluts”, walking the boardwalk of Copacabana Beach carrying placards in favor of abortion and women’s and gays’ rights. Some women walked down the street topless, while a group smashed figures of the Virgin Mary.

“The pope supported the demonstrations, but I don’t think he learned about the March of the Sluts, which I consider disrespectful to the Christian faith, by stepping on crucifixes and such”, says Frei Betto.

Theologian Leonardo Boff, another prominent Liberation Theology figure in Brazil, says the Pope’s humbler approach led to a more understanding view of the protesters, by defending young people’s “utopia” and “the right of them to be heard”.

“The biggest legacy is the figure of Pope Francis: a humble servant of faith, deprived of all pomp, touching and letting others touch him, speaking the language of young people and (telling) the truth with sincerity”, he posted on his blog.

Francis had arrived in Brazil on 22 July where he led World Youth Journey, an international Catholic event hosted in Rio de Janeiro. Hundreds of thousands of Catholics from all over the world flocked to Rio in order to have a closer look at the Pope, who assumed a more straight-forward, simpler approach towards followers than his predecessor, Benedict XVI.

Russian lawmaker Vitaly Milonov has suggested that every gay athlete and spectator who comes to Russia for the 2014 Games will be arrested. (The International Olympic Committee says that won’t happen.) And while it is not totally clear what the “gay propaganda” law specifically means, Global Post has a useful summary:

Reports of arrest for kissing or hold hands, wearing or using rainbows, or pro-gay activism have helped to clarify the definition of “propaganda” as “any statement, oral or otherwise, that is pro-gay.”

It is now illegal to even admit homosexuality in public. It is also illegal to equate the value of homosexual relationships with that of heterosexual relationships, and punishment does not apply solely to Russians.

Foreigners can be arrested and detained for up to 15 days, fined and deported.

So, basically, anything remotely gay, and you’re in prison. With that in mind, I suggest, to Milonov and the rest of Russia, that every sport be banned from the 2014 Winter Games.

Alpine skiing? The competitors wear rainbow-colored spandex, which is often associated with “gay” in popular culture.

Biathlon? Men. Holding guns. Discharging them into the air. Textbook phallic symbolism.

Bobsled? Four men in spandex, stuffed inside a penis-shaped capsule. You could also argue that women doing the same—being inside of the penis capsule, which is an anti-traditional-sex position—is just as evocative of disruption.

Cross-country skiing? See alpine skiing.

Curling? Women eschew traditional feminine attire for pants and polo shirts. Men crash large stones into large stones strategically placed by other men.

Figure skating? “I can say that the best figure-skating in the world is the Soviet school of figure skating,” said Milonov. I have no response.

Freestyle skiing? Women with sticks strapped to their feet stomp over moguls, which evoke breasts, and thus suggests a rejection of classical femininity.

Ice hockey? Wood-en sticks are used to slap a hard and cold object past a desexualized being covered in padding and shielded by a mask.

Luge? Men in spandex, laying backwards, in direct contrast with the traditional male posture of dominance. Women, erect and sliding through a giant tube, subverting the basic male-to-female sex act.

Nordic combined? One gay sport plus another gay sport equals a really gay sport.

Short track speed skating? Often results in members of the same sex piled on top of each other while wearing extremely tight clothing, and is therefore not too dissimilar from a public orgy.

Skeleton? The name itself is a rejection of the appearance and the living human characteristics which are the basis of traditional patriarchal society. That, therefore, is an inherently gay attitude.

Ski jumping? Both male and female posit themselves as human phallic symbols, hurtling through the air. That evocation of equality is gay.

Snowboarding? The sport was founded as a counter-cultural activity, which is gay.

Speed skating? Hooded spandex outfits obscure any suggestion of gender across all competitions, thus creating a space for any/all close readings of sexuality, which would not be the case in a climate where “gay” is considered illegal.

In short, ban the 2014 Winter Olympics from Russia.

This article originally appeared at Pacific Standard. Pacific Standard is an arm of the nonprofit Miller-McCune Center for Research, Media and Public Policy.

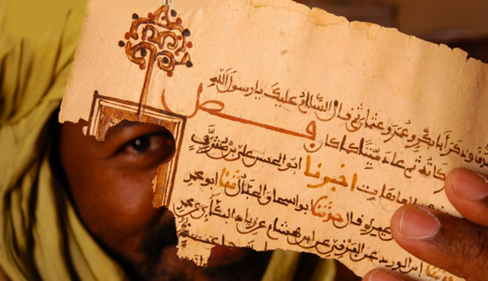

A public campaign has been launched to protect fragile manuscripts rescued from Timbuktu during the Mali crisis earlier this year. Sara Yasin reports

The campaign, called “Libraries in Exile”, is raising money for protection and storage for the documents. They are now threatened by moisture damage, thanks to inadequate storage and a change in humidity. The campaign will use donations to reverse existing damage, and to purchase moisture traps and archival boxes. Many of the texts were transferred to Bamako, the country’s southern capital.

The campaign, called “Libraries in Exile”, is raising money for protection and storage for the documents. They are now threatened by moisture damage, thanks to inadequate storage and a change in humidity. The campaign will use donations to reverse existing damage, and to purchase moisture traps and archival boxes. Many of the texts were transferred to Bamako, the country’s southern capital.

The ancient religious texts, some dating back 700 years, were initially thought to have been destroyed by rebels belonging to radical Islamist group Ansar Dine. At least 4,200 documents were damaged by either looting or arson during the crisis, but approximately 300,000 documents were saved.

A UN mission was sent to Mali to assess the damage, from 28 May to 3 June 2013. A programme specialist in UNESCO’s cultural section, David Stehl, told the Associated Press that “4,203 manuscripts were either burned by the Islamists or stolen.”

Most of the manuscripts were housed at the Ahmed Baba Institute, a state-owned library that became Ansar Dine’s headquarters when they captured Timbuktu in March 2012. While they initially did not know the value of the manuscripts, they eventually went looking for them. One of the institute’s employees, Alkamiss Cisse told the Washington Post that once the jihadists “heard of the manuscripts’ importance to the world, they would destroy them.”

In June 2012, fighters from Ansar Dine began destroying Timbuktu’s historic shrines and tombs for being “idolatrous.”

Timbuktu is a UNESCO world heritage site. The organisation listed it as “endangered” following Ansar Dine’s takeover of Mali’s government in March. Shortly before the fighters began destroying the shrines, UNESCO warned that the Ansar Dine’s presence might endanger the city’s “outstanding architectural wonders”.

Timbuktu Deputy Mayor Sandy Haidara told Reuters at the time that the attack was “a direct reaction to the UNESCO decision.”

A team of librarians and archivists risked their lives to smuggle the documents out of Timbuktu. The manuscripts, hailing from centres of medieval learning in Timbuktu, Arabia, Egypt, Morocco, Andalusia and Southern Europe, and the Arab trading ports on the Indian Ocean. Timbuktu was once a lively trading hub, and was key to Islam’s spread in West Africa.

Sara Yasin is an Editorial Assistant at Index. She tweets from @missyasin