20 Sep 2016 | Events, mobile

Join Index on Censorship and English PEN for a vigil outside the Turkish embassy in support of Ayşe Çelik and others currently persecuted for speaking out in Turkey. This vigil is part of a global campaign launched by the Initiative for Freedom of Expression – Turkey.

Çelik, a teacher, will stand trial beginning on Friday, accused of “promoting terrorist organisation propaganda” after she called in to a popular television entertainment show to plead for more media coverage of abuse and killings of civilians in Diyarbakir, south-east Turkey.

Thirty-one people who co-signed Çelik’s statement will also be tried alongside her. They all face more than seven years in prison if found guilty.

Index on Censorship stands with Ayşe Çelik and will not ignore this breach of her basic right to freedom of expression. We denounce the current crackdown undertaken by authorities in Turkey and call for the immediate and unconditional release of imprisoned writers Ahmet Altan, Mehmet Altan, Asli Erdogan and Necmiye Alpay.

We will be outside the Turkish embassy from 2pm to 3pm.

Here is the full statement that landed Çelik in court:

Are you aware of what’s going on in Southeast Turkey? Unborn children, mothers, people are being killed here. As a performer, as a human being you should not remain silent to what’s happening. You should say stop. I want to say one more thing. There are miserable people who are glad to hear that children are dying. We, more correctly I, cannot say anything to these people, but shame on you. I’m sorry I want to say one more thing. I’m a teacher and I’m asking all teachers (who fled the area): How will they ever go back to these places? How will they look at those innocent children’s faces and into their eyes? I can’t speak really. The things happening here are reflected so differently on TV screens or on the media. Don’t remain silent. As a human being, have a sensitive approach. See, hear and lend a hand to us. It’s a pity, don’t let those people, those children die; don’t let the mothers cry anymore. I can’t even speak over the sounds of the bombs and bullets. People are struggling with starvation and thirst, babies and children too. Don’t remain silent.

When: Friday 23 September 2pm

Where: 43 Belgrave Square, London SW1X 8PA (Map)

19 Sep 2016 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, mobile, Volume 45.03 Autumn 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Does anonymity need to be defended? Contributors include Hilary Mantel, Can Dündar, Valerie Plame Wilson, Julian Baggini, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Maria Stepanova “][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2”][vc_column_text]

The latest issue of Index on Censorship explores anonymity through a range of in-depth features, interviews and illustrations from around the world. The special report looks at the pros and cons of masking identities from the perspective of a variety of players, from online trolls to intelligence agencies, whistleblowers, activists, artists, journalists, bloggers and fixers.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”78078″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Former CIA agent Valerie Plame Wilson writes on the damage done when her cover was blown, journalist John Lloyd looks at how terrorist attacks have affected surveillance needs worldwide, Bangladeshi blogger Ananya Azad explains why he was forced into exile after violent attacks on secular writers, philosopher Julian Baggini looks at the power of literary aliases through the ages, Edward Lucas shares The Economist’s perspective on keeping its writers unnamed, John Crace imagines a meeting at Trolls Anonymous, and Caroline Lees looks at how local journalists, or fixers, can be endangered, or even killed, when they are revealed to be working with foreign news companies. There are are also features on how Turkish artists moonlight under pseudonyms to stay safe, how Chinese artists are being forced to exhibit their works in secret, and an interview with Los Angeles street artist Skid Robot.

Outside of the themed report, this issue also has a thoughtful essay by novelist Hilary Mantel, called Blot, Erase, Delete, about the importance of committing to your words, whether you’re a student, an author, or a politician campaigner in the Brexit referendum. Andrey Arkhangelsky looks back at the last 10 years of Russian journalism, in the decade after the murder of investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya. Uzbek writer Hamid Ismailov looks at how metaphor has taken over post-Soviet literature and prevented it tackling reality head-on. Plus there is poetry from Chilean-French director Alejandro Jodorowsky and Russian writer Maria Stepanova, plus new fiction from Turkey and Egypt, via Kaya Genç and Basma Abdel Aziz.

There is art work from Molly Crabapple, Martin Rowson, Ben Jennings, Rebel Pepper, Eva Bee, Brian John Spencer and Sam Darlow.

You can order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: THE UNNAMED” css=”.vc_custom_1483445324823{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Does anonymity need to be defended?

Anonymity: worth defending, by Rachael Jolley: False names can be used by the unscrupulous but the right to anonymity needs to be defended

Under the wires, by Caroline Lees : A look at local “fixers”, who help foreign correspondents on the ground, can face death threats and accusations of being spies after working for international media

Art attack, by Jemimah Steinfeld: Ai Weiwei and other artists have increased the popularity of Chinese art, but censorship has followed

Naming names, by Suhrith Parthasarathy: India has promised to crack down on online trolls, but the right to anonymity is also threatened

Secrets and spies, by Valerie Plame Wilson: The former CIA officer on why intelligence agents need to operate undercover, and on the damage done when her cover was blown in a Bush administration scandal

Undercover artist, by Jan Fox: Los Angeles street artist Skid Robot explains why his down-and-out murals never carry his real name

A meeting at Trolls Anonymous, by John Crace: A humorous sketch imagining what would happen if vicious online commentators met face to face

Whose name is on the frame? By Kaya Genç: Why artists in Turkey have adopted alter egos to hide their more political and provocative works

Spooks and sceptics, by John Lloyd: After a series of worldwide terrorist attacks, the public must decide what surveillance it is willing to accept

Privacy and encryption, by Bethany Horne: An interview with human rights researcher Jennifer Schulte on how she protects herself in the field

“I have a name”, by Ananya Azad: A Bangladeshi blogger speaks out on why he made his identity known and how this put his life in danger

The smear factor, by Rupert Myers: The power of anonymous allegations to affect democracy, justice and the political system

Stripsearch cartoon, by Martin Rowson: When a whistleblower gets caught …

Signing off, by Julian Baggini: From Kierkegaard to JK Rowling, a look at the history of literary pen names and their impact

The Snowden effect, by Charlie Smith: Three years after Edward Snowden’s mass-surveillance leaks, does the public care how they are watched?

Leave no trace, by Mark Frary: Five ways to increase your privacy when browsing online

Goodbye to the byline, by Edward Lucas: A senior editor at The Economist explains why the publication does not name its writers in print

What’s your emergency? By Jason DaPonte: How online threats can lead to armed police at your door

Yakety yak (don’t hate back), by Sean Vannata: How a social network promising anonymity for users backtracked after being banned on US campuses

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Blot, erase, delete, by Hilary Mantel: How the author found her voice and why all writers should resist the urge to change their past words

Murder in Moscow: Anna’s legacy, by Andrey Arkhangelsky: Ten years after investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya was killed, where is Russian journalism today?

Writing in riddles, by Hamid Ismailov: Too much metaphor has restricted post-Soviet literature

Owners of our own words, by Irene Caselli: Aftermath of a brutal attack on an Argentinian newspaper

Sackings, South Africa and silence, by Natasha Joseph: What is the future for public broadcasting in southern Africa after the sackings of SABC reporters?

“Journalists must not feel alone”, by Can Dündar: An exiled Turkish editor on the need to collaborate internationally so investigations can cross borders

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Bottled-up messages, by Basma Abdel Aziz: A short story from Egypt about a woman feeling trapped. Interview with the author by Charlotte Bailey

Muscovite memories, by Maria Stepanova: A poem inspired by the last decade in Putin’s Russia

Silence is not golden, by Alejandro Jodorowsky: An exclusive translation of the Chilean-French film director’s poem What One Must Not Silence

Write man for the job, by Kaya Genç: A new short story about a failed writer who gets a job policing the words of dissidents in Turkey

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view, by Jodie Ginsberg: Europe’s right-to-be-forgotten law pushed to new extremes after a Belgian court rules that individuals can force newspapers to edit archive articles

Index around the world, by

Josie Timms: Rounding up Index’s recent work, from a hip-hop conference to the latest from Mapping Media Freedom

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

What ever happened to Luther Blissett? By Vicky Baker: How Italian activists took the name of an unsuspecting English footballer, and still use it today

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483444808560-b79f752f-ec25-7″ taxonomies=”8927″ exclude=”80882″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483444808560-b79f752f-ec25-7″ taxonomies=”8927″ exclude=”80882″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 Sep 2016 | News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

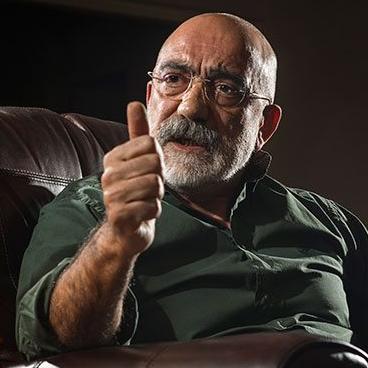

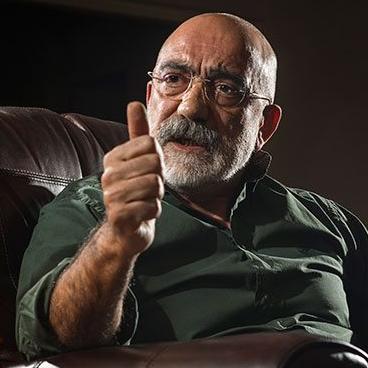

Jailed Turkish journalist Ahmet Altan.

If made out of the right stuff a journalist is a tough nut. Some of us are, you may say, born that way. Our profession lives in our cells. We are compelled to do what our DNA instructs us to do.

Yet, these days, I can’t help waking up each morning in a state of gloom.

Never before have we, Turkey’s journalists, been subjected to such multi-frontal cruelty. Each and every one of us have at least one — usually more — serious issue to wrestle with. Many have already faced unemployment. According to Turkey’s journalist unions, more than 2,300 media professionals have been forced to down pens since the coup attempt. The silenced face a dark destiny: they will never be rehired by a media under the Erdogan yoke.

More than 120 of my colleagues are in indefinite detention – and that number does not include 19 already sentenced to prison. The latest to be added to the list are the novelist and former editor of daily Taraf, the renowned journalist Ahmet Altan and his brother, Mehmet Altan, a commentator and scholar.

The grim pattern of arrests comes with a note attached: “To be continued…”

Nobel Laureate Orhan Pamuk recently and eloquently summed up what Turkey is becoming: “Everybody, who even just a little, criticises the government is now being locked in jail with a pretext, accompanied by feelings of grudge and intimidation, rather than applying law. There is no more freedom of opinion in Turkey!”

Some of those who are still free, either at home or abroad, may consider themselves lucky – or at least be perceived as such. But the reality is that each and every one of us faces immense hardship.

Being forced into an exile, as I have been, is not an easy existence. Many like me have an arrest warrant hanging over their heads. Others are simply anxious or unwilling to return home.

Pressured by financial strains, a journalist in exile bears the burden of the country they have been torn from while remaining glued to the agony of others.

But there is more. Last week I offered one of my news analyses to a tiny, independent daily — one of the very few remaining in Turkey. Waiving any fee, I asked the editor — who is a tough nut — to consider publishing it. Soon, the text was filed and the initial response was: “This one is great, we will run it.”

Then came a telephone call. Because the editor and I have a friendly relationship, he was open when he told me this: “As we were about to go online with it, one editor suggested we ask our lawyer. I thought he was right in feeling uneasy because everything these days is extraordinary. Then, the lawyer strongly advised against it. Why, we asked. He said that since Mr Baydar has an arrest warrant, publishing a text with his byline or signature would, according to the decrees issued under emergency rule, give the authorities to the right to raid the newspaper, or simply to shut it down. Just like that. Tell Mr Baydar this, I am sure he will understand.”

I did understand. No sane person would want to bear the responsibility for causing the newspaper’s employees to be rendered jobless, to be sent out to starvation.

I have since published piece elsewhere.

This incident is but one in a chain, hidden in Turkey’s relative freedom. It’s a cunning and brutal system of censorship that aims to sever the ties between Turkey’s cursed journalists and their readership. It is a deliberate construction of a wall between us and the public. It is putting us in a cage even if we are breathing freedom elsewhere.

It’s enough to make George Orwell turn in his grave.

But there is some consolation. Thankfully we, the censored among Turkey’s journalists, have space to write about the truth, make comments and offer analysis in spaces like Index on Censorship. Thankfully, we have the internet, which is everybody’s open property, even if the sense of defeat when you awake some mornings leaves you convulsing in the gloom.

You know you have to chase it away and get on with what you know best: to inform, to exchange views, offer independent opinion, promote diversity, and hope that one day it will contribute to democracy.

More Turkey Uncensored

Can Dündar: “We have your wife. Come back or she’s gone”

Turkey: Losing the rule of law

Yavuz Baydar: As academic freedom recedes, intellectuals begin an exodus from Turkey

13 Sep 2016 | mobile, News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

In mobster movies the bad guys always kidnap the wife of the protagonist. They’ll phone the husband to say: “We have your wife. Do as we tell you otherwise she’s gone.”

I had not imagined that a state could become no better than a criminal syndicate. But the Turkish state has become one.

On Saturday 3 September my wife’s passport was confiscated by the police at the airport as she was en route to Berlin. She was not accused of anything criminal. She was not being searched for or tried and had no obstacles preventing her from travelling abroad. There was no legitimate reason to prevent her journey and no explanation has been given.

It is with me that they had an issue. I had broadcast footage of Turkish state intelligence smuggling arms into a neighbouring country by illegal means. They could not deny it and say: “No such thing has happened.” What they said was: “This is a state secret.”

For uncovering the state’s dirty secrets, I was given five years and ten months in prison. We had appealed the conviction to a higher court but after the coup attempt a state of emergency was declared and the rule of the law was completely suspended.

To expect justice to be served by a judiciary under the complete control of the government would have been as naive as expecting mercy from the “mob”.

I went abroad and said that I would not return until the state of emergency was lifted and the rule of the law was restored.

Then the mob took my wife hostage. We are not the only people to face such relentlessness.

The 64-year-old mother-in-law of one of the supposed coup plotters was taken to a prison in a wheelchair. The father of another accused, who was not caught, was taken into custody as he left prayer in a mosque. The passports of wives and daughters have been confiscated and hundreds of families have been forcefully separated without trial.

These are direct violations of the principle of individual responsibility for crime.

Guilt by association allows such mob-like lawlessness prevails in a country that is a member of the Council of Europe.

It was the present government that brought the coup plotters who tried to overthrow it into the state, tasked them with cleansing its opponents and made a giant out of them.

When they had a dispute over distribution of spoils and dissolved their partnership, there remained within the state a well rooted and gargantuan parallel organisation.

Then the conflict peaked on July 15 when Frankenstein’s monster attacked its creator.

The violent coup attempt was put down because the military headquarters did not lend it support and the people took to the streets. But Erdogan has treated the event — in his own words — as “a godsend”. Using the tactics used by US senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s, he has started a witch hunt that will incarcerate all opposition.

More than 40,000 people have been taken into custody while 80,000 civil servants have been removed from their duties. Dozens of journalists have been arrested. Nearly 100 media outlets have been shut down.

Yet the rage of the government has not been quelled. Now it is taking it out on the relatives of those “witches” it did not catch.

It says: “We have your wife. Come back or she’s gone.”

But we all know that at the end of the movie the bad guys are defeated, the hostages are freed and families are reunited.

I have no doubt that this is what will happen in Turkey. Those who have made a mob out of the state will be tried. Families will get back together and celebrate the end of the witch hunt and the return of freedom, democracy and justice.

We are well aware of this and we labour to make that day come true.

Can Dündar: Turkey is “the biggest prison for journalists in the world”

Turkey should drop criminal charges against journalists Can Dündar and Erdem Gül