My book and the school library: Norma Klein

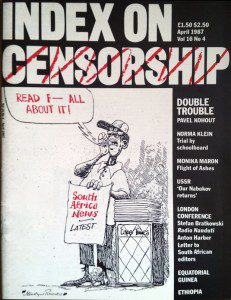

This article is part of the spring 1987 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by children’s book author Norma Klein, on the censorship of children’s books, taken from the spring 1987 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the Banned books: controversy between the covers session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

I used to feel distinguished, almost honoured, when my young books were singled out to be censored. Now, alas, censorship has become so common in the children’s book field in America that almost no one is left unscathed. Some of the most conservative writers are being attacked; it’s reached a point of ludicrousness which, for me, was symbolised by my most recent encounter with ‘the other side’ in Gwinett county, Georgia, in April 1986.

Usually, my books are attacked for their sexual content. The two school board meetings I had attended in the early 1980s, one in Oregon, one in the State of Washington, had centred on two books for older teens, It’s Okay if You Don’t Love Me, a book about two 18- year-olds having a love affair, and Breaking Up, a novel about a 15-year-old girl who discovers her mother is gay. I might add parenthetically that these books have just been published in England for the first time by Pan Books in a new series aimed at teenagers, ‘Horizons’. Already, as in America, they are selling well and already, as in America, I have been told of indignant parents storming into bookstores and objecting to certain passages. It seems that things are not very different in other countries.

What was unusual about the Gwinnett county case was that the book selected to be attacked was one of my early ones, Confessions of an Only Child, about an eight-year-old girl. The offending sentence was one where the girl’s father is putting up wallpaper. Here it is in its entirety:

‘God damn it,’ Dad said as the wallpaper swung around and whacked him in the face.

When the paperback publisher of Confessions first heard of the attack, he attempted to defend the book in the following way:

Abrasive words are sometimes used by writers to add definition to a character or a story; they give the reader an understanding of the situation or kind of person speaking, but are not meant to be words which the reader should use or admire. It is our belief that the family relationships are so positive in this book that they far outweigh the use of realistic language.

My attacker, Theresa Wilson, a stunning blonde, had been heartened by her success in having another book she objected to, Deanie by Judy Blume, removed from the shelves. Her first attempt to remove my book was defeated by a 10-member review panel consisting of six parents, three teachers and a librarian. Ms Wilson claimed to have ‘stumbled’ upon the offending passage one afternoon while in the Beaver Ridge library looking for books that contain material to which she might object. In her thirties, she has no profession and, in a sense, being a censor has led to her becoming a local celebrity; she now, whether her attacks succeed or fail, appears regularly on TV and radio and is covered widely in local newspapers. The 10-member panel voted to keep Confessions on the shelves; only one person voted to keep it on a restricted shelf. ‘The consensus is that the book had literary merit for the age group intended,’ said principal Becky Hopcraft.

Incidentally, Ms Wilson said she didn’t object to my heroine’s mother saying, ‘Ye Gods,’ in the next line, because she does not believe ‘Gods’ refers to the Christian god. She wants every book containing the word ‘damn’ restricted from Gwinnett elementary schools. She cited a US Supreme Court ruling against hostility toward religion and said the use of God Damn in Confessions indicated a ‘hostility toward Christianity’.

All this, the initial attack on my book and its initial success in being retained on the shelves, helped to achieve an important result — the founding of a group called Gwinnett Citizens for Freedom in Education. Initially a small group, it now has nearly 500 members. Its president, Lorna Cox, said she was amazed at the diversity of the group’s members, proving that liberals in America are not, as some right-wingers insist, an elitist minority. ‘We’ve got people who didn’t graduate from high school,’ Ms Cox said, ‘college graduates, doctors, professionals, and people who aren’t even affiliated with a school but have a deep, burning desire to be involved in education.’ The group participates in workshops to learn more about censorship at the local and national levels and contacts school administrators each week to learn about potential book bannings.

As in the cases involving It’s Okay if You Don’t Love Me, and Breaking Up, my travel expenses to Georgia were paid by the author’s organisation, PEN. They have a Freedom to Read committee with a fund for cases like this. My own reason for attending these meetings is that I feel having the author appear and help argue the case not only gives heart to the local anti-censorship organisations involved, such as Gwinnett Citizens for Freedom in Education, but may focus national attention on the case. Perhaps it was co- incidental, but CBS did appear in the courtroom to cover the debate for a TV segment on ‘secular humanism’.

Before flying to Georgia I was interviewed by phone. I was quoted as saying, ‘I’m not a religious person… To me the phrase god damn has no more negative a connotation than the expression, Oh gosh. I added that I attributed the swing toward censorship in America to the conservative mood of the Reagan administration. When I arrived, I was told by two of my supporters that the negative reference to Reagan was a mistake. ‘Everyone is for him down here,’ they said. I have to add parenthetically that one of the reasons I write the kinds of books I do and am, perhaps ingenuously, surprised at the reaction they provoke, is due to the fact that I’ve lived all my life in New York City and know personally only liberal people. I’ve never met anyone who voted for Reagan; I am always amazed when the Republicans win an election. But it’s probably similar that in a two-week stay in London’ in the spring of 1986,1 didn’t meet anyone who was for Margaret Thatcher either. This may, however, give me a kind of inner freedom from certain restrictions, due simply to underestimating the power of the right.

The school board meeting I attended was crowded with supporters from both sides. It was conducted as a kind of mock trial. Both sides were allowed to question anyone from the other side about anything that was relevant to the case. I was pleased and relieved that every time Ms Wilson tried to bring the questioning around to my own personal religious beliefs, she was told that was not relevant to the book. In a perverse way I found her performance at the trial fascinatiing. She alternately flirted with, and tried to antagonise, the three-member school board which consisted of two men and a woman. Luckily for me, her case was weak and she overstepped the bounds of tolerance — even within a conservative, religious community — by telling the school board members that if they didn’t ban my book, they would, on Judgment Day, go straight to Hell. ‘One day each and every one of you will stand before God almighty and you will answer to how’you believe, how you voted, how you stand.’ Evidently this threat did not frighten anyone sufficiently.

The closest Ms Wilson got to making me come forward and state my personal beliefs was when she asked if I considered myself to be ‘above God’. I responded, ‘I assume that’s a rhetorical question.’ She laughed nervously and said she didn’t know what ‘rhetorical’ meant.

Confessions of an Only Child is about a family in which the mother gets pregnant and loses her baby. It shows how this affects the heroine who was enjoying her only child status. In deciding that Confessions had ‘redeeming educational value’, one of the board members, Louise Radloff, stated, ‘I think this book has much literary merit and it shows an open discussion within the family’. I had argued in my presentation that I felt that books could be an avenue to open discussion… a way to bring parents and children closer together, that simply having a book available was not forcing it on anyone.

What amazed me, though, was that in their closing remarks, though each school board member re-iterated the literary values of my book, all three said that, indeed, the phrase ‘God damn’, was offensive and should have been left out. One board member said he, thank heaven, had never used that word. Another said he had used it once, at the age of 10 and had been beaten so severely by his parents for this that he had never used it again. I am utterly unable to judge the sincerity of these remarks. What I did feel was the pressure on everyone living in these suburban communities to conform to what is felt to be a general set of beliefs. People are terribly afraid to come out and say they are feminists, atheists, or even, God forbid, Democrats.

In a sense this is a success story. Not only will my book remain on the shelves, but the Gwinnett Citizens for Freedom in Education feel heartened that the positive publicity they received will help them in future battles. But Theresa Wilson is, seemingly, not daunted. She’s already after another book, Go Ask Alice. ‘I don’t love publicity,’ she said when interviewed on a local radio show the day after the hearing. ‘I love showing the glory of God.’ Sadly, even the local people who are against her regard her as good copy. Although she had lost her case, she was brought forward to be on the radio show with me and most of the time was spent, not debating the issues involved, but in baiting her with peculiar call-in questions from the audience. What a pity. But still, no matter how absurd and tiny this one case is, I feel I would do it again for my own books and would encourage other authors to do the same. Passivity and inaction only encourages censorship groups even more. I think now they are beginning to realise they will, at least, have a fight on their hands.

Reporting the Third World

World leaders, or their top ministers, in an effort to arrive at something we call ‘balanced coverage’. Most Third World leaders feel you are either for ’em or against ’em and there is not much middle ground to walk upon. Some, as in Saudi Arabia, just don’t want to talk to the Western press. I can remember one visit to the Saudi kingdom in early 1981 when four American correspondents — from the New York Times, Time magazine, the Associated Press, and myself from The Washington Post — jointly applied for an interview with either King Khalid or Crown Prince Fahd. Each of us knew it was unlikely either would bother with an interview for just one publication, but here was a broad segment of the US print media asking collectively for an interview. After waiting around for two weeks, we collectively gave up and left.

One major problem for American correspondents is the near total ignorance of Third World leaders about how the Western media work and how to use them for their own ends. While the correspondent may regard his or her request for an interview with a leader or top minister as a chance to air their views, they seem to look upon it as a huge favour which they are uncertain will be rewarded in any way.

Other forms of indirect censorship come in control over a correspondent’s access to the story or means of communication. Israel restricted, or at least tried to restrict, access to southern Lebanon after its invasion in June 1982 to those it felt were sympathetic to its cause or important to convince of its view. The policy never really worked because correspondents could always get into Israeli-occupied territory from the north through one back road or another. But it got more difficult as time went on. The Israeli attempt at restricting access to southern Lebanon was hardly the worst example of this kind of censorship I experienced in nearly two decades of working in the Third World, however. Covering the war between Iran and Iraq was, and remains, far more difficult. In four years, I never once got a visa to Iran. I got to Baghdad several times, but imagine my surprise the first time customs officials seized my typewriter at the airport and told me I would have to get special permission from the Information Ministry to bring it in. (At the airport in Tripoli there was a roomful of confiscated typewriters the last time I visited there in September 1984.) Whether one was allowed to the Iraqi war front depended on either an Iraqi victory or a lull in the war. As for permission to travel into Iraqi Kurdistan, it was never granted to any Western correspondent I can think of in the four-to-five years I was covering the Middle East.

The other game Iraqi information officials play is attempting to censor your coverage of the war. When I first went there, there was a Ministry of Information official sitting at the hotel who had to okay your copy or you could not send it out by phone or telex. This kind of direct censorship of copy was rare in my experience, however. Other than Israel, where military news is supposed to pass through the censor’s office, and Iraq and Libya, I can think of no examples where I had to submit my copy before sending it.

Are the techniques of indirect censorship getting worse? In the areas of the world where I have worked, I am not sure. If Syria has become worse, Iraq is probably better today. Egypt has definitely got better, and so had Kuwait until recently. Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, has restricted access to a far greater degree in the past two years, and Bahrain has become more sensitive. South Africa has taken a turn for the worse. Countries that were always difficult to cover, such as Zaire, Malawi, Ethiopia and Angola, remain more or less the same.

As economic problems have got worse or rulers have felt a greater threat to their regimes, Third World governments seem to be tightening up when it comes to outside press coverage.

If this is indeed the underlying principle governing the degree of press censorship, then the problem may be more cyclical than linear, getting worse or better according to the political and economic health of a country or the special challenges it is facing at that time.

Who believes it?

‘That is how the theory goes: Restrict the press to supportive comment, and a country’s life will be calmer and better. But experience and reason suggest that the opposite will happen. Faulty government policies, if they are not subject to real criticism, grow worse. Autocrats become more autocratic. Can anyone believe that repression of criticism leads to efficiency in a society, to new ideas?’

Anthony Lewis, The New York Times, February 1987

© Norma Klein and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the spring 1987 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

When Turkish journalists got hold of the

When Turkish journalists got hold of the