21 Dec 2023 | Afghanistan, Belarus, Bosnia, Brazil, China, Cuba, Ecuador, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Lebanon, Magazine Contents, Malta, Nigeria, Pakistan, Palestine, Russia, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States, Vietnam, Volume 52.04 Winter 2023

Contents

The Winter 2023 issue of Index looks at how comedians are being targeted by oppressive regimes around the world in order to crack down on dissent. In this issue, we attempt to uncover the extent of the threat to comedy worldwide, highlighting examples of comedians being harassed, threatened or silenced by those wishing to censor them.

The writers in this issue report on example of comedians being targeted all over the globe, from Russia to Uganda to Brazil. Laughter is often the best medicine in dark times, making comedy a vital tool of dissent. When the state places restrictions on what people can joke about and suppresses those who breach their strict rules, it's no laughing matter.

Up Front

Still laughing, just, by Jemimah Steinfeld: When free speech becomes a laughing matter.

The Index, by Mark Frary: The latest in the world of free expression, from Russian elections to a memorable gardener

Features

Silent Palestinians, by Samir El-Youssef: Voices of reason are being stamped out.

Soundtrack for a siege, by JP O'Malley: Bosnia’s story of underground music, resistance and Bono.

Libraries turned into Arsenals, by Sasha Dovzhyk: Once silent spaces in Ukraine are pivotal in times of war.

Shot by both sides, by Martin Bright: The Russian writers being cancelled.

A sinister news cycle, by Winthrop Rodgers: A journalist speaks out from behind bars in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Smoke, fire and a media storm, by John Lewinski: Can respect for a local culture and media scrutiny co-exist? The aftermath of disaster in Hawaii has put this to the test.

Message marches into lives and homes, by Anmol Irfan: How Pakistan's history of demonising women's movements is still at large today.

A snake devouring its own tail, by JS Tennant: A Cuban journalist faces civic death, then forced emigration.

A 'seasoned dissident' speaks up, by Martin Bright: Writing against Russian authority has come full circle for Gennady Katsov.

Special Report: Having the last laugh - The comedians who won't be silenced

And God created laughter (so fuck off), by Shalom Auslander: On failing to be serious, and trading rabbis for Kafka.

The jokes that are made - and banned - in China, by Jemimah Steinfeld: Journalist turned comedian Vicky Xu is under threat after exposing Beijing’s crimes but in comedy she finds a refuge.

Giving Putin the finger, by John Sweeney: Reflecting on a comedy festival that tells Putin to “fuck off”.

Meet the Iranian cartoonist who had to flee his country, by Daisy Ruddock: Kianoush Ramezani is laughing in the face of the Ayatollah.

The SLAPP stickers, by Rosie Holt and Charlie Holt: Sometimes it’s not the autocrats, or the audience, that comedians fear, it’s the lawyers.

This great stage of fools, by Danson Kahyana: A comedy troupe in Uganda pushes the line on acceptable speech.

Joke's on Lukashenka speaking rubbish Belarusian. Or is it?, by Maria Sorensen: Comedy under an authoritarian regime could be hilarious, it it was allowed.

Laughing matters, by Daisy Ruddock: Knock knock. Who's there? The comedy police.

Taliban takeover jokes, by Spozhmai Maani and Rizwan Sharif: In Afghanistan, the Taliban can never by the punchline.

Turkey's standups sit down, by Kaya Genç: Turkey loses its sense of humour over a joke deemed offensive.

An unfunny double act, by Thiện Việt: A gold-plated steak and a maternal slap lead to problems for two comedians in Vietnam.

Dragged down, by Tilewa Kazeem: Nigeria's queens refuse to be dethroned.

Turning sorrow into satire, by Zahra Hankir: A lesson from Lebanon: even terrible times need comedic release.

'Hatred has won, the artist has lost', by Salil Tripathi: Hindu nationalism and cries of blasphemy are causing jokes to land badly in India.

Did you hear the one about...? No, you won't have, by Alexandra Domenech: Putin has strangled comedy in Russia, but that doesn't stop Russian voices.

Of Conservatives, cancel culture and comics, by Simone Marques: In Brazil, a comedy gay Jesus was met with Molotov cocktails.

Standing up for Indigenous culture, by Katie Dancey-Downs: Comedian Janelle Niles deals in the uncomfortable, even when she'd rather not.

Comment

Your truth or mine, by Bobby Duffy: Debate: Is there a free speech crisis on UK campuses?

All the books that might not get written, by Andrew Lownie: Freedom of information faces a right royal problem.

An image or a thousand words?, by Ruth Anderson: When to look at an image and when to look away.

Culture

Lukashenka's horror dream, by Alhierd Bacharevič and Mark Frary: The Belarusian author’s new collection of short stories is an act of resistance. We publish one for the first time in English.

Lost in time and memory, by Xue Tiwei: In a new short story, a man finds himself haunted by the ghosts of executions.

The hunger games, by Stephen Komarnyckyj and Mykola Khvylovy: The lesson of a Ukrainian writer’s death must be remembered today.

The woman who stopped Malta's mafia taking over, by Paul Caruana Galizia: Daphne Caruana Galizia’s son reckons with his mother’s assassination.

21 Dec 2018 | Croatia, Hungary, Macedonia, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, Montenegro, News and features, Poland, Serbia

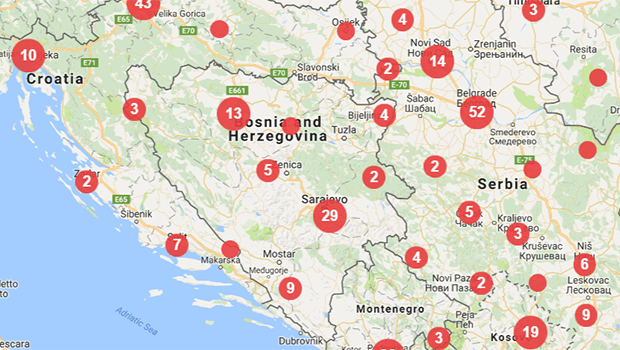

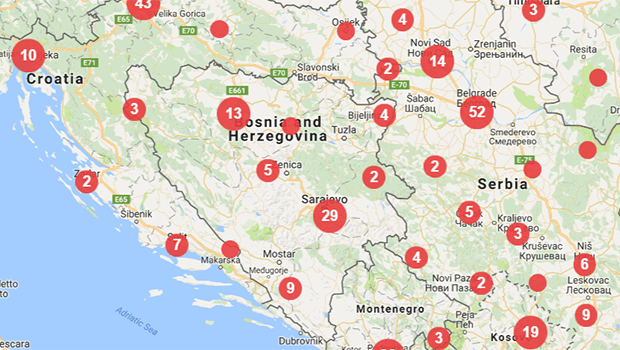

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image="104453" img_size="full" add_caption="yes"][vc_column_text]Additional reporting by Ada Borowicz, Ilcho Cvetanoski, Lazara Marinković and Zoltán Sipos

Unpatriotic behaviour. Sedition. Being in the pay of shadowy external forces. Faking a neo-Nazi event. These are just a few of the charges that have recently been levelled against independent journalists by pro-government media outlets in several central and eastern European countries.

The opening volley in a sustained campaign of vilification directed at Serbia's independent media was fired by the state-owned weekly Ilustrovana Politika at the end of October, with an article that accused journalists who are critical of the government of being “traitors and collaborators with the enemies of Serbia”.

Two weeks later, Ilustrovana Politika followed up with another piece that accused the veteran journalist Ljiljana Smajlović – who has long been critical of the nationalistic legacy bequeathed on the country by its former leader Slobodan Milosević and co-founded the Commission Investigating the Murders of Journalists in Serbia – of complicity in the 1999 NATO bombing of Belgrade.

In mid-December, Ilustrovana Politika’s campaign of character assassination against Smajlović ratcheted up another level with a garish front page depicting her as a Madonna figure with two naked infants bearing the features of Veran Matić, the chairman of the commission, and US Ambassador to Serbia Kyle Scott.

Smajlović has no doubt over what lies behind this tidal wave of denigration, of which she has become the prime target.

History repeating itself?

Editor Slavko Ćuruvija was murdered in 1999.

The long-running trial of four ex-members of the Serbian intelligence service accused of the murder of Dnevni Telegraf editor Slavko Ćuruvija – shot dead in April 1999 a few days after the pro-government Politika Ekspres accused him of welcoming the NATO bombardment – is now in its final stages, and Smajlović is convinced that the current campaign against her is designed to influence the judges in the case.

“The attacks come from the same Milosevic-era editors who also targeted my colleague Ćuruvija as a traitor prior to his assassination,” she told Mapping Media Freedom. “What is also sinister is that they are published and printed by the same state-owned media company that targeted Slavko nearly twenty years ago.”

“The clear implication is that I am the same kind of traitor as he was. How will that affect the judges? Will they fear this is not a good time to hold state security chiefs to account?” she added.

While Smajlović admits that Ilustrovana Politika’s denunciation has made her feel insecure, she insists she is less concerned for her own safety than worried about the consequences for the outcome of the Ćuruvija trial. Quoting Marx’s dictum that “History repeats itself, first as tragedy and then as farce”, Smajlović said. “I hope this is the farce part.”

Laying the blame

In Serbia and other central and eastern European countries, the assignment of responsibility for historic causes of resentment and the potential of these to further divide a polarised public often form the background to attacks on independent journalists by their state-approved colleagues.

The thorny topic of Poland’s relations with Germany during the last century recently gave pro-government media in Poland a chance to accuse independent media of being insufficiently patriotic and even of falsifying facts.

Journalist Bartosz Wieliński was targeted by the head of TVP Info's news site.

In November, after Bartosz Wieliński, a journalist with the independent daily Gazeta Wyborcza, gave a critical account of a speech made by the Polish ambassador to Berlin at a conference devoted to the centenary of Poland’s independence, the head of the state broadcaster’s news website, TVP Info, accused him of lying and of putting the interests of Germany before those of his own country.

Only a few days before this attack, two media outlets that support Poland’s ruling national-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party accused the independent US-owned channel TVN of fabricating the evidence on which a report about the resurgence of neo-Nazism in Poland was based.

Since it came to power in 2015, PiS – which has been accused by its critics of tolerating organisations that espouse far-right ideologies – has put pressure on independent media outlets, many of which are foreign-owned, as part of its campaign to “re-polonise” the media, and now appears to be using the public broadcaster and other tame outlets as accessories in this drive.

Willing accomplices

In Hungary, where the government led by Viktor Orbán has succeeded in imposing tight control on all but a few determinedly independent media outlets, a number of loyal publications are available for the purposes of vilification.

2015 Freedom of Expression Journalism Award winner Tamás Bodoky, founder of Atlatszo.hu

In September, a whole raft of pro-government media outlets vied with each other to depict Tamás Bodoky, the editor-in-chief of the investigative journalism platform Átlátszó and winner of the 2015 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for Journalism, as a “Soros hireling”. Bodoky became the target of a co-ordinated smear campaign after he posted on Facebook a picture of himself taken in Brussels with Dutch Green MEP Judith Sargentini, whose report on the Fidesz government’s infringement of core EU values had formed the basis for the European parliament’s censure motion against Hungary a few weeks earlier.

Another Hungarian journalist, András Dezső, who works for the independent news website Index.hu, also recently came under attack from pro-government media outlets after a Budapest court let him off with a reprimand over a case in which he was alleged to have made unauthorised use of personal information. In an article published before April’s general election, Dezső had cast doubt on the account of a woman who declared on Hungarian TV that she felt safer in Budapest than in Stockholm because of the lower level of immigration in Hungary. The airing of the interview by the public broadcaster was seen as providing support for Fidesz’s anti-immigration stance and aiding its election victory.

A criminal charge was issued against Dezső for “misuse of personal data”, and after he received what was described in the Hungarian media as “the mildest possible punishment”, two pro-government news websites, 888.hu and Origo.hu, accused him of deliberately propagating fake news and seeking to mislead his readers.

Why do they do it?

What motivates those journalists who smear their colleagues who seek to hold power to account?

There does not appear to be a simple answer to this question. While some may vilify fellow journalists to order purely for financial gain (or because of a desire for job security, government-sponsored media outlets generally being on a more secure financial footing than their independent counterparts), some appear to approach the task with at least a measure of conviction.

Ilcho Cvetanoski, who reports on Bosnia, Croatia, Macedonia and Montenegro for Mapping Media Freedom and has observed many smear campaigns over the years, believes that financial and ideological motivating factors are often inextricably intertwined. He points out that two decades on from the armed conflicts in the region, Balkans societies are still deeply divided along ideological and ethnic lines, and many people still find it extremely difficult to accept the right of others to see things differently. Cvetanoski notes that there are many “true believers” who are genuinely convinced that they have a duty to defend their country from the “other” – a group in which they tend to lump critical journalists along with mercenaries, spies and traitors.

Lazara Marinković, who covers Serbia for Mapping Media Freedom, believes that the main motivation there is a need to be on the winning side and to please those in power. “Often they actually enjoy doing it, either for ideological reasons or because they feel more powerful when they are on the side of the ruling party,” she told Mapping Media Freedom. Marinković noted that the majority of Serbian tabloids and TV stations that conduct smear campaigns against independent journalists are owned by businessmen who have close links to President Aleksandar Vučić’s national conservative Serbian Progressive Party (SNS). Vučić began his political career during the Milosević era, when he served as Minister of Information.

In Poland, the divisions in society and the consequent lack of tolerance in political culture have been blamed for the increasing polarisation of the media. Michal Głowacki, a professor of media studies at Warsaw University, told Mapping Media Freedom that journalists take their cue from politicians in failing to show respect for fellow journalists associated with the “other side”. “They even use the same language as politicians,” Głowacki notes.

This is a view echoed by Hungarian journalist Anita Kőműves, a colleague of Bodoky’s at Átlátszó. Kőműves, however, insists that while journalists who work for independent media outlets strive to uphold the principles of journalistic ethics, the same cannot be said of those employed by pro-government outlets. “Some of those serving the government at propaganda outlets think that the two 'sides' of the Hungarian media are equally biased and that they are not acting any differently from their counterparts in the independent media sphere. However, this is not true: pro-government propaganda outlets do not adhere to even the basic rules of journalism,” she told Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][vc_raw_html]JTNDaWZyYW1lJTIwd2lkdGglM0QlMjI3MDAlMjIlMjBoZWlnaHQlM0QlMjI0MDAlMjIlMjBzcmMlM0QlMjJodHRwcyUzQSUyRiUyRm1hcHBpbmdtZWRpYWZyZWVkb20udXNoYWhpZGkuaW8lMkZ2aWV3cyUyRm1hcCUyMiUyMGZyYW1lYm9yZGVyJTNEJTIyMCUyMiUyMGFsbG93ZnVsbHNjcmVlbiUzRSUzQyUyRmlmcmFtZSUzRQ==[/vc_raw_html][vc_basic_grid post_type="post" max_items="4" element_width="6" grid_id="vc_gid:1545385969139-cb42990e-b3e2-3" taxonomies="9044"][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Aug 2016 | Bosnia, mobile, News and features

University professors, poets and artists signed an open letter in support of three media workers who were targeted with death threats and hate speech. The letter, which was published in the Sarajevo daily Oslobodjenje on 21 July, said that the journalists are “targeted just because they expressed their view which is different from the majority’s”.

“Regardless of whether one agrees or not with the above-mentioned views, instigation of death threats and public lynching through creating a modern day Bosnian Index Librorum Prohibitorum is unacceptable,” the letter said.

The cases were reported to Mapping Media Freedom over three days in July.

In the first incident, Vuk Bacanovic, a journalist for the Radio-Television of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, was fired for allegedly violating the internal rules and the ethical code of the television network. In a Facebook post on his personal page he criticised a public art installation that depicted the federal entity of Republika Srpska as a mass grave and concentration camp. Bacanovic wrote that he “hates the assholes from Sarajevo” who were “talking crap” by saying the city has a multi-ethnic spirit. After articles about the post were published, Bacanovic received numerous death threats via Facebook, regional TV outlet N1 reported.

Nenad Velickovic, editor-in-chief of educational career-oriented magazine Skolegijum, was then verbally harassed and threatened as a result of three articles written by Filip Mursel Begovic, editor-in-chief of the weekly Stav, which were published in June and July. Begovic described Velickovic as a “man with a hidden and dangerous agenda”, “a falsifier” and a “Serbian nationalist” while describing the magazine Skolegijum as “extended arm of Serbian chauvinism”, Analiziraj.ba reported.

The letter was also written in support of the secretary general of BH Journalists’ Association Borka Rudic, who was subjected to verbal harassment by unidentified men after a high-ranking member of the Party of Democratic Action, an ethnic Bosniak political party, described her, amongst other things, as a “lobbyist for Fethullah Gulen”, website media.ba, reports.

The three incidents reflect the ethnic divisions and stereotypes that were re-enforced by the 1992-1995 war in Bosnia. The post-conflict society is governed through a complex political system established by the 1995 Dayton Peace Accords. The power-sharing constitution recognises each of the three major ethnic groups – Bosniaks (Muslims), Serbs (Orthodox) and Croats (Catholics) – as the constituent peoples of Bosnia. In practice, the recognition means that anyone not identified as belonging to one of the three groups could not be elected to hold a public office, despite a 2009 European Court of Human Rights ruling ordering the constitution to be revised.

Following the formula set out in the Dayton Accords, Bosnia and Herzegovina is divided into two entities – the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with majority ethnic Bosniak and ethnic Croatian inhabitants, and the Republika Srpska, with majority ethnic Serbian population. Additionally there is the district of Brcko, which is separate enclave jointly administered by both.

The three groups also differ on the future of Bosnia. Some Bosniaks advocate for a more unitary state, while some Serbs want a more confederate arrangement or even dissolution of the state. At the same time there are Croats that want a separate ethnic entity. The competing visions of Bosnia's future are heavily influenced by historic and recent incidents including charges of genocide, crimes against humanity and other atrocities that occurred during the 1992-95.

The Centre for Security Governance says that the governing structure “has discouraged inter-group cooperation and reconciliation. Political elites have pandered to ethnic fears, resulting in the electoral victories of ethnonational parties via the phenomenon of ‘ethnic outbidding’.”

Some politicians use friendly media to advocate for further strengthening of ethnic politics, while journalists and intellectuals that argue for strengthening civic identities and bridging ethnic hatred are usually vilified as traitors if they are from the same ethnic background, or enemies, if they are from another ethnicity. All of the cases addressed in the open letter originated in Bosniak nationalist media and were targeted at either another ethnicity or individuals who prefer civic above ethnic identity. Velickovic was described as a “man with a hidden and dangerous agenda” by a Bosniak journalist because he was advocating for non-nationalistic school curriculum.

"The importance of maintaining strong journalistic ethics cannot be underscored enough, especially given the country's recent history. Members of the media profession must strive to be balanced, refrain from inflaming already tense inter-ethnic relations and guard against being used for political ends," Hannah Machlin, project officer for Index on Censorship's Mapping Media Freedom, said.

Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, in an open letter also noted that the latest events open a very worrying chapter on the safety of journalists.

“People engaged in investigative reporting and expressing different opinions, even provocative ones, should play a legitimate part in a healthy debate and their voices should not be restricted,” Mijatovic said.

In the current climate, the open letter in support of and signed by people of different ethnicities is a small step forward. Signatory Asim Mujkic, a professor at the faculty of political sciences at the University of Sarajevo, said the cases were a call to action.

“My initial motive was to protest against the mainstream hegemonic ideological view that aggressively imposes itself upon independent and free-thinking intellectuals and public workers that, in the context of Bosnia and Herzegovina, usually targets vulnerable ethnicities for the purpose of its political mobilization,” Mujkic told Index on Censorship.“We need to fire back, especially in such circumstances.”

29 Jul 2016 | Bosnia, Europe and Central Asia, Macedonia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Poland, Turkey, United Kingdom

Click on the dots for more information on the incidents.

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Turkey: Warrants issued for arrest of 89 journalists

Turkish authorities have issued two lists of journalists to be arrested since the 15 July failed military coup attempt in the country. Firstly, on 25 July, authorities issued the names of 42 journalists as part of an inquiry into the coup attempt. Well-known commentator and former parliamentarian Nazli Ilicak was among those for whom a warrant was issued, as was Ercan Gun, the head of news department at Fox TV in Turkey.

Two days later, 27 July, authorities issued warrants for the detention of 47 former executives or senior journalists of the newspaper Zaman. The arrests were part of a large-scale crackdown on suspected supporters of US-based Muslim cleric Fethullah Gulen, accused by Ankara of masterminding the failed coup. The authorities shut down Zaman in March. At least one journalist, former Zaman columnist Şahin Alpay, was detained at his home early on Wednesday.

26 July, 2016 – Media Print Macedonia, the publisher of several daily and weekly newspapers, announced that it would dismiss 20 staff members, mostly experienced journalists and former editors from the daily Vest.

Layoffs are also to include employees from daily Utrinski Vesnik, Dnevnik, Makedonski Sport and weekly magazine Tea Moderna.

MPM stated layoffs were prompted by bad results and that the decision on who to dismiss would be based on the company’s internal procedures. Employees who lose heir jobs are to be compensated from one up to five average salaries, TV Nova reported.

24 July, 2016 - Emir Talirevic, a doctor who owns Moja Klinika, a private healthcare institution in Sarajevo, used Facebook to insult Selma Ucanbarlic, a journalist for the Centre for Investigative Journalism, following her articles about Moja Klinika, regional TV outlet N1 reported.

On 24 July Talirevic wrote on Facebook, among other things, that “judging by her psycho-physical attributes [the journalist] should never be allowed to do more complex work than grilling a barbecue”. He alleged hers were “imbecilic findings”, adding that “her work requires higher IQ than 65”.

In a second post, published on 27 July, Talirevic wrote that “as the toilet tank is taking away my associations on Selma and her CIN(ical) website I am thinking about the oldest profession in the world – prostitution”. He also wrote: “CIN is financed by gifts, like prostitutes”, and “after today’s article at least we know for whom Selma Ucanbarlic and her CIN colleagues are spreading their legs”.

22 July, 2016 – Masza Makarowa, a former journalist for the Russian language division of national broadcaster Polskie Radio, left the station due to a repressive climate and censorship, she claimed on her Facebook page.

An “atmosphere of scare tactics and paranoia” was prevalent at the broadcaster, Makarowa said. She also claimed that the station management instructed staff on which sources to consider for publication to Russian-speaking audiences, approving right-leaning, pro-governmental websites while explicitly prohibiting liberal sources like Gazeta Wyborcza for being opinionated. Certain updates, furthermore, were removed from the website.

22 June, 2016 - Jeff Howell, who had been writing a home maintenance advice column for The Telegraph for 17 years, was allegedly dismissed and removed from the Telegraph website after comments he made to his property section editor, Anna White.

According to Private Eye, the column, which was initially published both on the website and online, was removed from the website after he made a joke to property section editor White about correcting the Telegraph's editing errors following a typo in January. Much of the column's online archive was deleted following the incident.

Howell's page on the Telegraph website used to get up to 10,000 hits daily but the removal of most of his columns from the website "made it easy to justify his dismissal by saying he didn't produce any online traffic".