Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

|

|

Since becoming a journalist almost 30 years ago, Pakistani journalist Hamid Mir has had to choose between his life and his career. Mir is now one of Pakistan’s best-known journalists, the host of Geo Television’s flagship political show Capital Talk. He also now lives under armed guard, recovering from yet another assassination attempt, with his family sent abroad for their safety.

“My family is not happy with me,” he told Index. “They think that my life is more important than the profession.” Mir does not agree.

“I think that if I leave Pakistan, it’s like I surrender, and I don’t want to surrender to the Taliban, I don’t want to surrender to the rogue elements in our intelligence agencies and the security agencies. I don’t want to surrender to the enemies of democracy.”

Mir became a journalist after his father, who himself taught journalism at the University of the Punjab, died in mysterious circumstances in 1987. Mir saw his career as a continuation of his father’s fight for democracy, human rights and minorities’ rights in Pakistan.

“When I decided to become a journalist, Pakistan was ruled by a military dictator,” Mir told Index. It was not long after he started at a small paper in Lahore that Mir first met the violent opposition to his reporting that would characterise his career and life.

“When I started facing trouble, I was not aware that I was touching some controversial subject,” he said. “I was only doing my job as a reporter.”

In 1990, Mir broke a story about the military establishment and the then-president trying to remove the democratically elected Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto.

“I was kidnapped by the intelligence agency and they tortured me and asked me to tell them who is my source.” Bhutto’s government was removed days later.

Fast forward 30 years and Mir is still reporting on issues many Pakistani journalists won’t touch.

His tireless and outspoken reporting has earned him enemies in Pakistan’s intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence, the Pakistani Taliban and local terrorist groups, and Pakistan’s political parties.

It has also earned him a lifetime of assassination attempts – the latest a near-fatal attack in 2014 which saw him shot six times as he drove to work – has left Mir living under constant protection. He is driven to and from work in a bulletproof vehicle, alternating between cell phones and residences, and away from his two children, who were sent abroad after a car they were riding in was attacked.

But, for Mir, reporting on these untouchable-topics is not a question. “Maybe it’s controversial for the others but it’s not controversial for me,” he says.

“If a military dictator is suspending the constitution of Pakistan which was approved by the elected parliament, and I, being a journalist and a TV anchor, am opposing that, for me it’s not controversial,” he says.

“And again, if some intelligence agency is trying to dictate me – you should report this and you should not report that – and if the religious extremists, the Taliban, they are issuing threats to women, they are bombing the girls’ schools, and I am criticising the Taliban. I don’t think that it’s controversial.”

Threats to his life intensified in late 2015, and under pressure from his family, Mir planned to take three months off-air.

“After one month, I realised that it’s too much, I have to come back.”

For Mir, if not for his family, his duty to Pakistan and to his colleagues, will always outweigh his own safety. The guilt he feels for those journalists who have died for their work is too great to ever allow him to stop, he says.

“There were some colleagues who used to come to me and take advice about what should we do because we are facing pressures. Should we continue our job as a journalist? I used to advise them, yes you must continue your job as a journalist, nothing bad will happen. But they were killed, they were kidnapped.”

“If I leave Pakistan today, on the pressure of my family, maybe I will leave a very safe life in London or in Berlin or in Paris or in any other country. But it will be very difficult for me to live a normal life, because the ghosts of my martyred friends, they will not allow me to have a comfortable sleep.”

Mir believes he is one of the lucky ones in Pakistan – he has survived. And life in Lahore is a lot easier for journalists than for those living outside the city, he says.

Although he sees media freedom in Pakistan getting worse, with pressures from the extremist forces and state agencies intensifying, his long-view is an uplifting one.

“The good thing is that the people, the majority of the people of Pakistan, the civil society, is the main source of our strength. If I am living in Pakistan, if I am surviving in Pakistan, it’s only because the common man is supporting me,” he said.

“The common man believes in democracy, they don’t like extremist ideology, they don’t like dictatorship, they want rule of law. There is a ray of hope for me in Pakistan.”

Bolo Bhi, which means “speak up” in Urdu, is a non-profit run by a powerful all-female team, fighting for internet access, digital security and privacy in Pakistan and around the world. Founded in 2012 by Sana Saleem and Farieha Aziz, they have since fought tirelessly to challenge Pakistan’s increasingly pervasive internet censorship.

|

|

“In the year 2012 the government were trying to bring in a national URL filtering firewall along the lines of China,” Farieha Aziz told Index.

“Then came the YouTube ban in September 2012. We lead a campaign against that and got commitments from businesses around the world not to bid for the tender the government of Pakistan had floated.”

The team have now launched countless internet freedom programmes, published research papers, fought for gender-rights, government transparency, executed successful campaigns and run digital security training sessions all over Pakistan.

“In Pakistan the internet is an unlegislated space, so a lot of our work involves discussions law and policy, and the shape they should be taking and the shape they should not be taking,” says Aziz.

Their biggest fight to date has been taking on the draconian Prevention of Electronic Crimes (PEC) Bill. The proposed legislation includes the criminalisation of political criticism and political expression in the form of analysis, commentary, blogs and cartoons, caricatures, memes; “obscene” or “immoral” messages on social media; posting of photographs of anyone on Facebook or Instagram without their permission; and sending an email or message without the recipient’s permission.

“We were able to get a leaked copy [of the bill] and we went public and we started forming an alliance,” said Aziz. “Our part was really to get people on board and collect people to collectively resist the bill in its current form.”

At every stage of the bill’s dramatic progression, Bolo Bhi been tirelessly campaigning against and shedding light on the legislation, which would have otherwise been quietly passed. They have created a timeline tracking cybercrime legislation with information on every development.

They also organised a series of press conferences, media events and campaigns to raise public awareness about the bill, as well as facilitating a series of consultations on the proposed cybercrime law with activists, lawyers and technology experts.

“Over a period of a year from advocating, trying to get the media to talk about it, we saw that a lot of people, even citizens, were very concerned about it. Across the board this concern resonated and nobody wanted the bill in the form it existed. We thought it would pass in a month, but it’s been almost a year and it’s been held off.”

Last year they also took down Pakistan’s Inter-Ministerial Committee for the Evaluation of Websites, filing a petition in the Islamabad High Court challenging the legality of committee, which is responsible for all official decisions taken to block online content in Pakistan. After a court ruling in March 2015, the IMCEW was disbanded – a win for Bolo Bhi, until the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority was given powers for content management on internet. Bolo Bhi continue to fight against the restrictions.

As well as shaping the debate around internet freedom in Pakistan, Bolo Bhi campaigns tirelessly for women’s rights.

“Gender is an integral part of what we do at Bolo Bhi. Recently we’ve tackled acid crimes, which are particularly perpetrated against women. We launched a social media campaign but we’ve also worked with women’s groups.”

Freedom of expression in Pakistan is a complicated phrase, Aziz says. But Bolo Bhi’s work ensures it is not one that is left unexamined.

Acrassicauda concert at The Roxy in Hollywood, 10 June 2010. Credit: Flickr / Bruce Martin

Underground music scenes have begun sprouting up in many countries around the world in the last few years, where previously no such thing existed. These movements have managed, in many cases, to continue despite a continuing trend of censorship in the arts and government repression. Whether it be punks in Indonesia rebelling against Sharia law or hip-hop artists in Mumbai rapping about independence from Britain, people all over the world are fighting for their right to artistic freedom. Here are a few cities around the world where musicians refused to be silenced.

Even after social activist and creator of The Second Floor, a cafe that promotes discussion, performance and art, Sabeen Mahmud was murdered by armed motorcyclists in Karachi in April 2015, the experimental and electronic music culture has continued to grow. Refusing to be intimidated into silence, artists like Sheryal Hyatt, who records as Dalt Wisney and founded Pakistan’s first DIY netlabel, Mooshy Moo, and the producing pair of Bilal Nasir Khan and Haamid Rahim, who created the electronic label and collective Forever South, are challenging conventional ideas about the music culture in Karachi.

Punk music is one of the ultimate forms of expressing disdain for a system of oppression, so it comes as no surprise that so many youths in Indonesia have embraced the genre with a passion. The punk scene, which grew exponentially following the 2004 tsunami when a great many lost family members and help from the government was less than forthcoming. The hostility and discrimination against the punk subculture came to a head in 2012 when police rounded up 64 youths at a concert, arrested them and took them to a nearby detention centre to have their mohawk hairstyles forcibly shaved. Despite this, bands like Cryptical Death continue to promote their scene and pen songs about resisting repressive government figures.

The vitality of punk music is also present in Burma, where musicians have been advocating for human rights through fast-paced music since around 2007. No U Turn and the Rebel Riot are popular punk groups that routinely rail against a government that they feel is repressive and unjust. No U Turn sounds like a resurrection of Bad Religion-meets-Naked Raygun with a blend of biting lyrics and punishing speed.

Indian hip-hop pioneers have been appearing more and more in the last 10 years, with Abhishek Dhusia, aka ACE, forming Mumbai’s Finest, the city’s first rap crew, and Swadesi, another local group whose work they think represents feelings and ideals of many young people in the city. Swadesi, in particular, advocates for social justice within their band’s mission, with working for NGOs and organising events being an important element of their group.

Musicians in Iraq have faced a variety of oppressive control, ranging from young people being stoned to death by Shi’ite militants for wearing western-style “emo” clothes and haircuts to Acrassicauda, a popular heavy-metal band from Baghdad, receiving death threats from Islamic militants. Acrassicauda had to flee the country a few years after the USA invaded Iraq, going first to Syria and then to the USA, where they were given refugee status and from where they now continue to make music. They have hopes of touring the Middle East soon but have no idea when they will be able to return to Iraq.

Index on Censorship has teamed up with the producers of an award-winning documentary about Mali’s musicians, They Will Have To Kill Us First, to create the Music in Exile Fund to support musicians facing censorship globally. You can donate here, or give £10 by texting “BAND61 £10” to 70070.

The anti-terror charges against reporters for Vice News in Turkey are not isolated. In recent years, a number of countries have used broad anti-terror laws to restrict the freedom of the press.

Turkey

British journalists Jake Hanrahan, left, and Philip Pendlebury and Iraqi translator and journalist Mohammed Ismael Rasool were filming clashes between pro-Kurdish youths and security forces, according to Vice. (Photos: Vice News)

Two British journalists and a local fixer working for Vice News were charged on Monday 31 August in Turkey with “working on behalf of a terrorist organisation”. They will remain in detention until their trial, the date of which has not yet been announced.

The journalists Jake Hanrahan, Philip Pendlebury and Iraqi translator and journalist Mohammed Ismael Rasool were filming clashes between security forces and youth members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in the south-eastern city of Diyarbakir on Thursday when they were arrested.

Turkey’s broad definition of terrorism means that any journalist reporting on PKK activities or Kurdish rights can be charged with the offence of making “terrorist propaganda” and jailed.

Index on Censorship Chief Executive Jodie Ginsberg said: “Coming just days after the unjust sentencing of three Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt, these latest detentions of journalists simply for doing their jobs underlines the way in which governments everywhere can use terror legislation to prevent the media from operating.”

Egypt

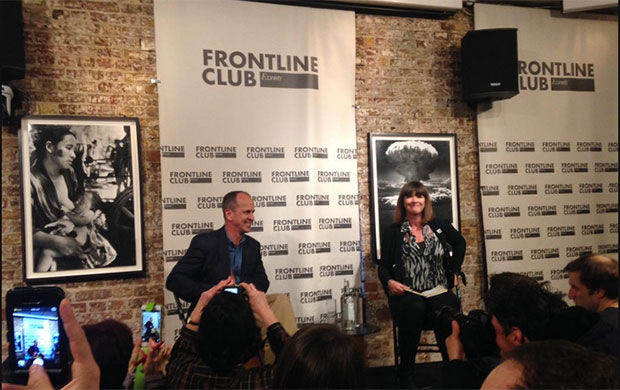

Peter Greste spoke to a Frontline Club audience about his arrest and detention in Egypt. (Photo: Milana Knezevic / Index on Censorship)

Egypt remains a cause for concern when it comes to press freedom: on 29 August 2015 Al Jazeera journalists Mohamed Fahmy, Peter Greste and Baher Mohamed were sentenced to three years in prison. The journalists were found guilty of of “broadcasting false information” and “aiding a terrorist organisation” – a reference to the Muslim Brotherhood.

The sentencing came just weeks after President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s government passed an anti-terror law setting a fine of up to 500,000 Egyptian pounds (£41,600) for journalists who stray from government statements or spread “false” reports on attacks or security operations against armed fighters.

Jordan

Abdullah II of Jordan at a conference in Amman in 2013. Ahmad A Atwah / Shutterstock.com

Jordan introduced a new “anti-terror” law in 2006 prohibiting, among other things, the engagement in “acts that expose the kingdom to risk of hostile acts, disturb its relations with a foreign state, or expose Jordanians to acts of retaliation against them or their money”. The charge carries a prison sentence of three to 20 years. The law was amended in 2014 to , broaden the definition of terrorism.

Interpretation of the law has been varied. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), in April 2015 a journalist was jailed for criticising the Saudi-led bombing of Houthi forces in Yemen. Another journalist was detained in July 2015 for breaking a recent ban on coverage of a terror plot. Earlier in 2015, an activist who criticised the royal family’s support of Charlie Hebdo on Facebook was sentenced to five months in jail under the anti-terror law.

Tunisia

One month after June’s terrorist attack on Sousse beach killing 38 tourists, for which ISIS claimed responsibility, Tunisia approved new anti-terror legislation.

Under the legislation, website editor Nour Edine Mbarki was charged in connection with publishing a photograph of a car that purportedly transported a gunman behind the beach attack. According to the CPJ, he was charged under Article 18 of the law with “complicity in a terrorist attack and facilitating the escape of terrorists,” which carries a prison term of between five and 12 years. He is currently awaiting a trial date.

Human Rights Watch said the new anti-terror bill “would open the way to prosecuting political dissent as terrorism, give judges overly broad powers, and curtail lawyers’ ability to provide an effective defence”.

Pakistan

Rights groups have long criticised Pakistan’s notorious anti-blasphemy laws for their effect on freedom of expression in the country. But strengthened anti terror legislation is also impacting the way journalists operate in the country.

In June, three Pakistani journalists were charged under the Anti-Terrorism Act, reportedly for covering the activities of a dissident politician, according to the Pakistan Press Foundation. A year before, a TV anchor was also charged under the law.

One to watch: Kenya

Following two separate attacks by al-Shabab militants in December, Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta signed into law a new security bill that could curtail press freedom. Under the new law, journalists could face up to three years in jail if their reports “undermine investigations or security operations relating to terrorism” – or even if they published images of “terror victims” without police permission.

This hasn’t come into play yet – in February, the Kenyan High Court threw out several clauses, including those that could impact media freedom. The government has said it would consider lodging an appeal.

This post was written by Emily Wight for Index on Censorship

This article was posted on 1 September 2015 at indexoncensorship.org