5 Oct 2016 | Asia and Pacific, Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2016, News and features, Pakistan

Farieha Aziz, director of 2016 Freedom of Expression Campaigning Award winner Bolo Bhi (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Pakistan’s Prevention of Electronic Crimes Bill 2015, better known as the cyber crimes bill, has severe implications for freedom of expression and the right to access information in the country.

After a lengthy process, the bill was signed into law on 22 August 2016. Bolo Bhi, the Pakistani non-profit promoting digital freedoms and winner of the 2016 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression award for campaigning, has been fighting the bill through all it’s stages and will continue to do so even now it has been approved.

“We are looking at what will be the right approach and the current debate is whether we jump to court and challenge it on constitutional grounds or wait for there to be an executive review and then build a case around it,” Farieha Aziz, director of Bolo Bhi, told Index on Censorship.

Bolo Bhi has reached out to other organisations and individuals, including the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan and several lawyers, during its campaign against the bill, and if legal action is to be taken it will be a class action involving all of all of these parties.

“We’ve gotten some of the best constitutional minds in the country to start looking at the law and where we go from here,” Aziz said.

Such action would be costly and, as pro bono doesn’t always guarantee success, the group have begun reaching out to people who may be able to provide support.

At this early stage amendments to the bill won’t be possible. “So we want to build pressure through public dialogue in terms of what’s wrong with the bill and what needs to be fixed,” Aziz said. “We will also raise awareness of how this law can be used against various communities.”

Pakistan has a large youth population – they very people having most conversations online – and they need to know how the bill will impact them, Aziz explained, so Bolo Bhi has been doing a lot of work with students. “We want to see the youth take ownership of this issue and see that discussion around such laws should not be relegated to the legal fraternity or the legislature.”

In terms of building pressure, the movement needs that student community voice. “It’s something we can’t leave untapped,” said Aziz.

Fighting the bill took up a lot of Bolo Bhi’s time over the past year and the organisation doesn’t currently have a staff beyond Aziz and fellow director Sana Saleem, nor an office in which to work from.

But fortunes may be changing. As Index spoke with Aziz, a possible fund to cover operational costs and salaries for a year was on the cards for Bolo Bhi. The organisation has always been small and even with this funding it would remain so, allowing it to stay focused on certain issues.

“And maybe in the next month or two we will even have an operational office again,” Aziz added.

With this in mind, Aziz is hopeful that Bolo Bhi will be send more time on its gender work. “We’re members of the Women’s Action Forum and with the recent passing of the anti-domestic violence bill there’s been a lot of discussion on the provincial protection of women, so that’s something we are focusing on,” she said.

On a case-by-case basis, a lot of victims and survivors of abuse get in touch with the network. “Just yesterday we spoke to a young girl who was forcibly married at 15, is now divorced with a young child and is being harassed by her own family,” Aziz explained. “We’re now trying to get protection and see what legal proceedings are necessary.”

This is just some of the work that goes on on the side and is what Aziz hopes she can do more of in future.

As always, the main challenge is funding.

“While it’s important for us to keep on top of the issues, at the same time we’re trying to get enough support to keep us afloat.”

Also read:

Smockey: “We would like to trust the justice of our country”

Zaina Erhaim: Balancing work and family in times of war

Artist Murad Subay worries about the future for Yemen’s children

GreatFire: Tear down China’s Great Firewall

Nominations are now open for 2017 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards. You can make yours here.

31 Jul 2013 | News and features, Pakistan, Religion and Culture

Asianet-Pakistan / Shutterstock.com

This article was originally published at Dawn.com

Dear Parliamentarians,

I write to you in the hope of assisting you in a rather arduous task being assigned to you by the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA). If recent reports are to be believed, the Pakistan telecommunication authority has done the unthinkable; in a rare moment of clarity the PTA has requested the parliament to define ‘blasphemy’.

Yes, after the country’s governor was shot 27 times for seeking pardon for a blasphemy accused mother, his murderer garlanded by lawyers and defended by the ex-Chief Justice of the Lahore High Court, a 14-year-old young girl and her family driven out of the country, a 70-year-old mentally unstable woman sentenced to 14 years in jails, several hundred burnt houses and dozens of lynched dead bodies later, you’ve finally been approached to determine what exactly classifies as blasphemy.

If you ask me, it’s rather strange that none of the incidents – or call them random acts of insanity – I summarised were able to do what a B-grade filmmaker was able to achieve. But then again, priorities! We are a nation of strange people and reactions; we forgive the unforgivable and punish ourselves for the crimes of others.

Without wasting much time, I’d want to discuss the important issue at hand. Now that you’ve been given the responsibility of defining blasphemy for the nation, given how difficult it is to be specific, and government policies are by their nature vague, I’d say go with enlisting instances of blasphemy for clarity’s sake:

- One commits blasphemy each time they harm another in the name of religion.

- One commits blasphemy each time they incite hatred for another in the name of religion.

- One commits blasphemy each time they justify murder in the name of religion.

- One commits blasphemy each time they persecute another for their faith or lack of it.

- One commits blasphemy each time they infringe the right to freedom of expression, opinion or movement of another, in the name of religion.

For the biggest form of blasphemy that we all almost always commit is to force another to live in fear for believing, speaking, thinking and sometimes even existing, as we justify it in the name of our faith or stand silent as we bear witness.

No videos, sketches or hate speeches have hurt Islam more than the reckless army of blood thirsty goons justifying vandalism in the name of religion.

There doesn’t exist a form of disrespect bigger than justifying cold-blooded murder and hate in God’s name. To instill fear and lawlessness in the society and to justify that as an act of faith. End the insanity now, tell the nation that we aren’t all potential blasphemers waiting to be lynched as and when the opportunity arises.

Trust me; it might do a lot more than just unblocking YouTube.

Yours,

A fellow potential blasphemer

12 Apr 2012 | Asia and Pacific, Digital Freedom

The past few months have seen the rise of a vocal and sophisticated anti-censorship campaign in Pakistan that has effectively shamed the government into shelving its plans for a national internet filtering system.

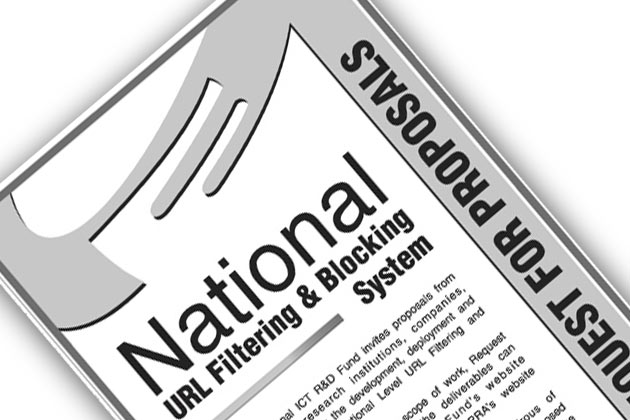

The Pakistan government’s ICT research and development fund issued a call in February for proposals from academia and companies for the development of a large-scale filter to block websites deemed “undesirable”.

According to the call, Pakistani internet service providers (ISPs) and backbone providers had “expressed their inability to block millions of undesirable web sites using current manual blocking systems.”

The document goes on to specify that the system should allow for the blocking of up to 50 million URLs with a processing delay of “not more than 1 milliseconds [sic]”. Were it to succeed, such a blanket system would put Pakistan’s internet on a par with the surveillance and filtering of China’s Great Firewall.

Human rights groups Bolo Bhi and Bytes for All have called on companies not to respond to the bid for proposals. Their methods seem to have worked, with five companies, including Websense, McAfee and Cisco saying they will not bid. Websense issued the following statement last month:

Broad government censorship of citizen access to the internet is morally wrong. We further believe that any company whose products are currently being used for government-imposed censorship should remove their technology so that it is not used in this way by oppressive governments.

The grassroots campaign has also garnered international attention, with a global coalition of NGOs, including Index, Article 19 and the Global Network Initiative, calling for the withdrawal of Pakistan’s censorship plans.

For Jillian C York, director for International Freedom of Expression at the San Francisco-based Electronic Frontier Foundation, the support of, rather than initiation by, international groups has been key. “I think that it was a combination of strong Pakistani organisations working with international organisations in tandem that made this campaign so big,” York said in an email. “Bolo Bhi and Bytes for All made the campaign a local one, using the language they preferred, but were smart enough to get the right organisations to amplify their voices while still maintaining control of the tone. I think that’s the example that they set.”

“I don’t see a company going forward with it now because there’s been public outrage and naming and shaming,” Sana Saleem, CEO of Bolo Bhi (“speak up” in Urdu), told Index. “There has been consistent effort and collaboration (…) It is tempting to shout but we said ‘let’s sit down first’. If we were reactionary it would make it hard for businesses to join us.”

In addition to appealing to companies and receiving international support, activists continued to contact the Pakistani government. Eventually a member of the National Assembly notified Bolo Bhi that the country’s secretary of IT had confirmed to her that the proposals had been shelved. Yet no official statement has been released, with Bolo Bhi and other civil society members planning to file a consititutional petition tomorrow. Saleem says the verbal commitment could be seen as a delaying tactic, arguing that now is the time to “consistently build on the campaign.”

Saleem says the Pakistani government has been looking for more control of the internet — which is accessed by 20 million of the country’s 187 million population — and that the filtering proposals could give rise to blanket surveillance. The vagueness of the terms “objectionable content” and “national security” in the terms of reference might also make the plans prone to abuse.

The proposals also threaten secure, encrypted web browsing available via https. “Something that has always annoyed intelligence agencies is not being able to access https,” Saleem said, noting that the government currently needs a court order if they wish to monitor particular users. The proposals would essentially absolve ISPs of the responsibility of blocking content manually.

Her fear is where the filtering would stop. “If we allow the state to be our moral police, it could be pornography today and something else tomorrow,” she said, citing a case late last year in which the PTA issued directives to ISPs to block 1,000 pornographic websites.

Given its apparent backtracking, Saleem predicts that the government will now be more careful in how it approaches internet filtering and surveillance. “The government made a huge mistake in making the proposals public, so they might be more covert in the future.” She adds that more controversial issues of morality and blasphemy will continue to pose a challenge in the country. “These are very charged issues,” she said, adding: “when we talk about internet freedom and freedom of expression, the government will continue to use these [issues] as a shield to exert control.”

Saleem’s aim now is to get more stakeholders involved in a broader debate about Pakistan’s national security, starting by holding discussions with university students. “Ideally we’d want the internet to be completely free, but we do know Pakistan is a police state. This is a time when we can sit down and see what we want to do.”

Marta Cooper is an editorial researcher at Index. She tweets at @martaruco.