28 Jun 2016 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, mobile, Volume 45.02 Summer 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index on Censorship has dedicated its milestone 250th issue to exploring the increasing threats to reporters worldwide. Its special report, Truth in Danger, Danger in Truth: Journalists Under Fire and Under Pressure, is out now.”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Highlights include Lindsey Hilsum, writing about her friend and colleague, the murdered war reporter Marie Colvin, and asking whether journalists should still be covering war zones. Stephen Grey looks at the difficulties of protecting sources in an era of mass surveillance. Valeria Costa-Kostritsky shows how Europe’s journalists are being silenced by accusations that their work threatens national security.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76283″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Kaya Genç interviews Turkey’s threatened investigative journalists, and Steven Borowiec lifts the lid on the cosy relationships inside Japan’s press clubs. Plus, the inside track on what it is really like to be a local reporter in Syria and Eritrea. Also in this issue: the late Swedish crime writer Henning Mankell explores colonialism in Africa in an exclusive play extract; Jemimah Steinfeld interviews China’s most famous political cartoonist; Irene Caselli writes about the controversies and censorship of Latin America’s soap operas; and Norwegian musician Moddi tells how hate mail sparked an album of music that had been silenced.

The 250th cover is by Ben Jennings. Plus there are cartoons and illustrations by Martin Rowson, Brian John Spencer, Sam Darlow and Chinese cartoonist Rebel Pepper.

You can order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. It has produced 250 issues, with contributors including Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: DANGER IN TRUTH, TRUTH IN DANGER” css=”.vc_custom_1483444455583{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Journalists under fire and under pressure

Editorial: Risky business – Rachael Jolley on why journalists around the world face increasing threats

Behind the lines – Lindsey Hilsum asks if reporters should still be heading into war zones

We are journalists, not terrorists – Valeria Costa-Kostritsky looks at how reporters around Europe are being silenced by accusations that their work threatens national security

Code of silence – Cristina Marconi shows how Italy’s press treads carefully between threats from the mafia and defamation laws from fascist times

Facing the front line – Laura Silvia Battaglia gives the inside track on safety training for Iraqi journalists

Giving up on the graft and the grind – Jean-Paul Marthoz says journalists are failing to cover difficult stories

Risking reputations – Fred Searle on how young UK writers fear “churnalism” will cost their jobs

Inside Syria’s war – Hazza Al-Adnan shows the extreme dangers faced by local reporters

Living in fear for reporting on terror – Ismail Einashe interviews a Kenyan journalist who has gone into hiding

The life of a state journalist in Eritrea – Abraham T. Zere on what it’s really like to work at a highly censored government newspaper

Smothering South African reporting – Carien Du Plessis asks if racism accusations and Twitter mobs are being used to stop truthful coverage at election time

Writing with a bodyguard – Catalina Lobo-Guerrero explores Colombia’s state protection unit, which has supported journalists in danger for 16 years

Taliban warning ramps up risk to Kabul’s reporters – Caroline Lees recalls safer days working in Afghanistan and looks at journalists’ challenges today

Writers of wrongs – Steven Borowiec lifts the lid on cosy relationships inside Japan’s press clubs

The Arab Spring snaps back – Rohan Jayasekera assesses the state of the media after the revolution

Shooting the messengers – Duncan Tucker reports on the women investigating sex-trafficking in Mexico

Is your secret safe with me? – Stephen Grey looks at the difficulties of protecting sources in an age of mass surveillance

Stripsearch cartoon – Martin Rowson depicts a fat-cat politician quashing questions

Scoops and troops – Kaya Genç interviews Turkey’s struggling investigative reporters

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Rebel with a cause – Jemimah Steinfeld speaks to China’s most famous political cartoonist

Soap operas get whitewashed – Irene Caselli offers the lowdown on censorship and controversy in Latin America’s telenovelas

Are ad-blockers killing the media? – Speigel Online’s Matthias Streitz in a head-to-head debate with Privacy International’s Richard Tynan

Publishing protest, secrets and stories – Louis Blom-Cooper looks back on 250 issues of Index on Censorship magazine

Songs that sting – Norwegian musician Moddi explains how hate mail inspired his album of censored music

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

A world away from Wallander – An exclusive extract of a play by late Swedish crime writer Henning Mankell

“I’m not prepared to give up my words” – Norman Manea introduces Matei Visniec, a surreal Romanian play where rats rule and humans are forced to relinquish language

Posting into the future – An extract from Oleh Shynkarenko’s futuristic new novel, inspired by Facebook updates during Ukraine’s Maidan Square protests

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Index around the world: Josie Timms recaps the What A Liberty! youth project

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

The lost art of letters – Vicky Baker looks at the power of written correspondence and asks if email can ever be the same

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 May 2016 | Bosnia, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Russia, Turkey, United Kingdom

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

The Russian state media regulator Roskomnadzor began blocking Krym Realii, the Сrimean edition of Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty on Saturday 14 May.

A representative of Roskomnadzor confirmed that the regulator had blocked a page, which contains an interview with a leader of the Tatar Mejlis, at the request of the general prosecutor office. “Currently, Roskomnadzor is implementing measures for blocking and closing this website,” criminal prosecutor Natalia Poklonskaya told Interfax.

Krym Realii was established following the annexation of Crimea to Russia. Materials on the site are published in Russian, Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar languages.

Several editors at RBC media holding lost their jobs on 13 May following a meeting between top management with journalists. They include RBC editor-in-chief Elizaveta Osetinskaya, editor-in-chief of the RBC business newspaper Maksim Solyus, and RBC deputy chief editor Roman Badanin.

In a press release, RBC underlined that the dismissals were finalised as a mutual agreement of both parties, but sources from TV-Dozhd and Reuters claim managers have bowed to political pressure from the Kremlin.

The pressure against RBC began following investigations that have reportedly “irked the Kremlin“, including one on the assets of Vladimir Putin’s alleged daughter, Ekaterina Tikhonova.

Petar Panjkota, a journalist for the Croatian commercial national broadcaster RTL, was physically assaulted after he had finished a segment from the Bosnian town Banja Luka on 14 May.

Panjkota was reporting on parallel rallies in Banja Luka, the administrative centre of Bosnia’s Serb-dominated of Republika Srpska. He was reporting on protests organised by the ruling and opposition parties of the Bosnian Serbs. When he went off air, Panjkota was punched in the head by an unidentified individual, leaving bruises.

RTL strongly condemned the attack, calling it another attack on media freedom. No information has surfaced on the identity of the assailant.

On 12 May, the long-awaited white paper on the future of the BBC was unveiled. The BBC Trust is to be abolished and replaced by a new governing board including ministerial appointees. The board will be comprised of 12 to 14 members: the chair, deputy chair and members for each of the four nations of the UK will be appointed by the government and the remaining seats will be appointed by the BBC.

“It is vital that this appointments process is clear, transparent and free from government interference to ensure that the body governing the BBC does not become simply a mouthpiece for the government,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship, said.

“Independence from government is essential for the BBC and these proposals don’t quite offer that,” Richard Sambrook, director of the Centre for Journalism at Cardiff School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies and former BBC journalist, told Index on Censorship. “There is no reason the board can’t be appointed by an arms length, independent panel. Currently the plans are too close to a state broadcasting model.”

Two reporters working for Dicle News Agency (DİHA) reporters were detained in the eastern city of Van on 12 May. Nedim Türfent and Şermin Soydan were allegedly detained within the scope of an on-going investigation and taken to the anti-terror branch in the central Edremit district of Van.

Both were detained separately. According to Bestanews website, Nedim Türfent was detained when his car was stopped by state forces at the entrance of Van. Şermin Soydan was detained on her way to cover news in the city of Van.

7 Jan 2016 | France, Mapping Media Freedom, News, Statements, United Kingdom

When I started working at Index on Censorship, some friends (including some journalists) asked why an organisation defending free expression was needed in the 21st century. “We’ve won the battle,” was a phrase I heard often. “We have free speech.”

There was another group who recognised that there are many places in the world where speech is curbed (North Korea was mentioned a lot), but most refused to accept that any threat existed in modern, liberal democracies.

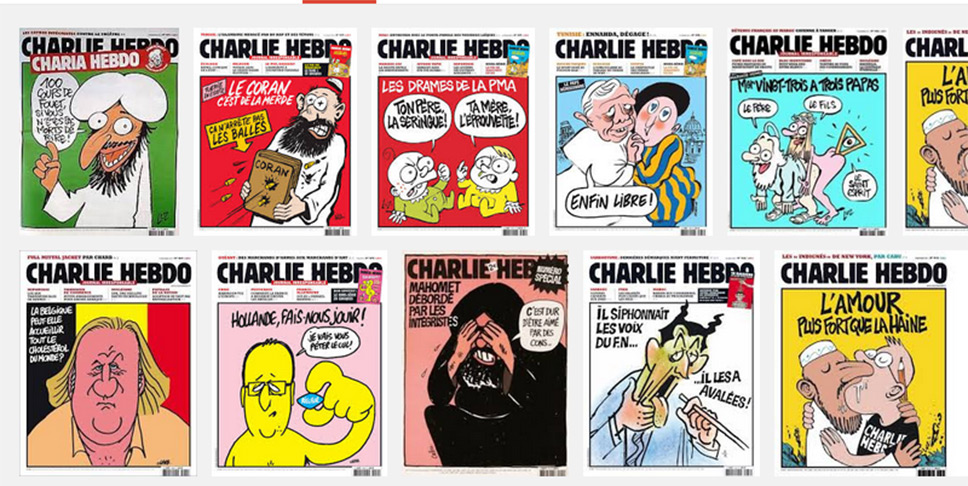

After the killing of 12 people at the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, that argument died away. The threats that Index sees every day – in Bangladesh, in Iran, in Mexico, the threats to poets, playwrights, singers, journalists and artists – had come to Paris. And so, by extension, to all of us.

Those to whom I had struggled to explain the creeping forms of censorship that are increasingly restraining our freedom to express ourselves – a freedom which for me forms the bedrock of all other liberties and which is essential for a tolerant, progressive society – found their voice. Suddenly, everyone was “Charlie”, declaring their support for a value whose worth they had, in the preceding months, seemingly barely understood, and certainly saw no reason to defend.

The heartfelt response to the brutal murders at Charlie Hebdo was strong and felt like it came from a united voice. If one good thing could come out of such killings, I thought, it would be that people would start to take more seriously what it means to believe that everyone should have the right to speak freely. Perhaps more attention would fall on those whose speech is being curbed on a daily basis elsewhere in the world: the murders of atheist bloggers in Bangladesh, the detention of journalists in Azerbaijan, the crackdown on media in Turkey. Perhaps this new-found interest in free expression – and its value – would also help to reignite debate in the UK, France and other democracies about the growing curbs on free speech: the banning of speakers on university campuses, the laws being drafted that are meant to stop terrorism but which can catch anyone with whom the government disagrees, the individuals jailed for making jokes.

And, in a way, this did happen. At least, free expression was “in vogue” for much of 2015. University debating societies wanted to discuss its limits, plays were written about censorship and the arts, funds raised to keep Charlie Hebdo going in defiance against those who would use the “assassin’s veto” to stop them. It was also a tense year. Events discussing hate speech or cartooning for which six months previously we might have struggled to get an audience were now being held to full houses. But they were also marked by the presence of police, security guards and patrol cars. I attended one seminar at which a participant was accompanied at all times by two bodyguards. Newspapers and magazines across London conducted security reviews.

But after the dust settled, after the initial rush of apparent solidarity, it became clear that very few people were actually for free speech in the way we understand it at Index. The “buts” crept quickly in – no one would condone violence to deal with troublesome speech, but many were ready to defend a raft of curbs on speech deemed to be offensive, or found they could only defend certain kinds of speech. The PEN American Center, which defends the freedom to write and read, discovered this in May when it awarded Charlie Hebdo a courage award and a number of novelists withdrew from the gala ceremony. Many said they felt uncomfortable giving an award to a publication that drew crude caricatures and mocked religion.

Index’s project Mapping Media Freedom recorded 745 violations against media freedom across Europe in 2015.

The problem with the reaction of the PEN novelists is that it sends the same message as that used by the violent fundamentalists: that only some kinds of speech are worth defending. But if free speech is to mean anything at all, then we must extend the same privileges to speech we dislike as to that of which we approve. We cannot qualify this freedom with caveats about the quality of the art, or the acceptability of the views. Because once you start down that route, all speech is fair game for censorship – including your own.

As Neil Gaiman, the writer who stepped in to host one of the tables at the ceremony after others pulled out, once said: “…if you don’t stand up for the stuff you don’t like, when they come for the stuff you do like, you’ve already lost.”

Index believes that speech and expression should be curbed only when it incites violence. Defending this position is not easy. It means you find yourself having to defend the speech rights of religious bigots, racists, misogynists and a whole panoply of people with unpalatable views. But if we don’t do that, why should the rights of those who speak out against such people be defended?

In 2016, if we are to defend free expression we need to do a few things. Firstly, we need to stop banning stuff. Sometimes when I look around at the barrage of calls for various people to be silenced (Donald Trump, Germaine Greer, Maryam Namazie) I feel like I’m in that scene from the film Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels where a bunch of gangsters keep firing at each other by accident and one finally shouts: “Could everyone stop getting shot?” Instead of demanding that people be prevented from speaking on campus, debate them, argue back, expose the holes in their rhetoric and the flaws in their logic.

Secondly, we need to give people the tools for that fight. If you believe as I do that the free flow of ideas and opinions – as opposed to banning things – is ultimately what builds a more tolerant society, then everyone needs to be able to express themselves. One of the arguments used often in the wake of Charlie Hebdo to potentially excuse, or at least explain, what the gunmen did is that the Muslim community in France lacks a voice in mainstream media. Into this vacuum, poisonous and misrepresentative ideas that perpetuate stereotypes and exacerbate hatreds can flourish. The person with the microphone, the pen or the printing press has power over those without.

It is important not to dismiss these arguments but it is vital that the response is not to censor the speaker, the writer or the publisher. Ideas are not challenged by hiding them away and minds not changed by silence. Efforts that encourage diversity in media coverage, representation and decision-making are a good place to start.

Finally, as the reaction to the killings in Paris in November showed, solidarity makes a difference: we need to stand up to the bullies together. When Index called for republication of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons shortly after the attacks, we wanted to show that publishers and free expression groups were united not by a political philosophy, but by an unwillingness to be cowed by bullies. Fear isolates the brave – and it makes the courageous targets for attack. We saw this clearly in the days after Charlie Hebdo when British newspapers and broadcasters shied away from publishing any of the cartoons featuring the Prophet Mohammed. We need to act together in speaking out against those who would use violence to silence us.

As we see this week, threats against freedom of expression in Europe come in all shapes and sizes. The Polish government’s plans to appoint the heads of public broadcasters has drawn complaints to the Council of Europe from journalism bodies, including Index, who argue that the changes would be “wholly unacceptable in a genuine democracy”.

In the UK, plans are afoot to curb speech in the name of protecting us from terror but which are likely to have far-reaching repercussions for all. Index, along with colleagues at English PEN, the National Secular Society and the Christian Institute will be working to ensure that doesn’t happen. This year, as every year, defending free speech will begin at home.

9 Dec 2015 | Campaigns, mobile, Statements

Index on Censorship opposes the proposal to ban Donald Trump from entering the UK.

“Donald Trump should not be banned from entering the UK. The best way to tackle views with which you disagree, including bigoted ones, is to allow discussion about them to take place so they can be openly countered. If you feel people’s arguments are hateful then the best way to expose that is in debate. Banning people just adds to their status and often increases their profile, and makes the arguments more popular. It does nothing to eradicate those views,” Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg said.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]