Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This article is part of Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist’s Project Exile series, which has published 52 interviews with exiled journalists from 31 different countries.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

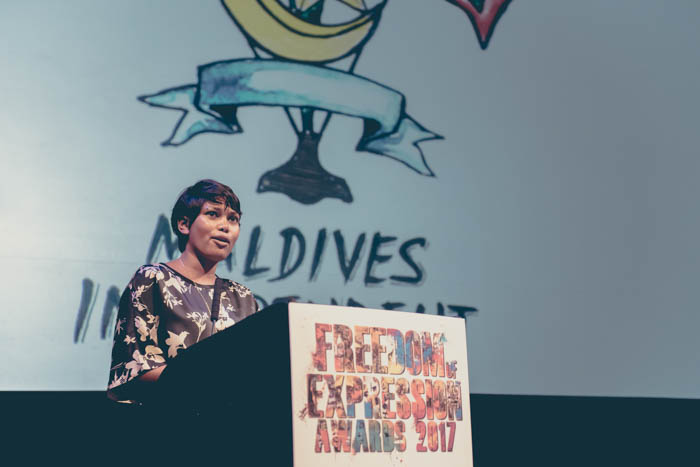

2017 Freedom of Expression Journalism Fellow Zaheena Rasheed, Maldives Independent (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

For many tourists, the Maldives is a resort destination with straw-thatched luxury bungalows perched atop the clear blue Indian Ocean. But for journalist Zaheena Rasheed, this small island nation, located off the southwest coast of India, is home. At least, it was.

Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards 2017 Journalism Fellow Rasheed, who was born in the Muslim-majority archipelago of 400,000 and attended college in the USA, developed an interest in journalism in 2008 when she took a semester off school to intern at the Maldives Independent news site. While there, she covered the country’s first multiparty elections, in which human rights activist and former political prisoner Mohamed Nasheed defeated longtime dictator Mamoon Abdul Gayoom.

Rasheed went to work full-time at the Independent and began climbing the ranks, but her professional life took a turn in 2012 after the democratically-elected Nasheed was forced from power and the space for the independent press and government criticism began closing. In 2014 a colleague who was known for criticising Islamists and the government, Ahmed Rilwan, went missing. By 2015, she was editor-in-chief of the Independent, but the political situation in the Maldives had worsened. The former president Nasheed was jailed and eventually went into exile in the UK while travelling there for medical treatment.

Press freedoms worsened in August 2016 when the new president Abdullah Yameen signed into a law a sweeping criminal defamation law that carried large fines and jail terms for slander as well as speech that threatens “social norms” or national security. Rasheed and 16 others journalists were detained for protesting the law.

By then Rasheed had earned the government’s ire through the Independent’s investigation into Rilwan’s disappearance as well as corruption in Yameen’s government. A tipping point came when she appeared in an explosive Al Jazeera investigative documentary in September 2016 called “Stealing Paradise.” The program implicated the highest reaches of Yameem’s government in a $1.5 billion international money laundering scheme.

Knowing she would face repercussions, Rasheed fled to Sri Lanka just days before the documentary was released. Hours after it appeared online, police raided the offices of the Maldives Independent.

“Sri Lanka, in many ways, has been the first stop for Maldivian dissidents,” Rasheed says, in an interview with Global Journalist. “It’s housed many, many different Maldivian dissidents, politicians, journalists, human rights defenders over the years, over the decades.”

Rasheed continued to edit the Independent remotely, but in April 2017 she moved to Qatar and accepted a reporting job with Al Jazeera.

Currently living in Doha, the 29-year-old spoke with Global Journalist’s Rayna Sims about witnessing firsthand the decline of press freedom in the Maldives and her hopes of returning home. Below, an edited version of their interview:

Global Journalist: What have been some of the effects of the anti-defamation law in the Maldives?

Rasheed: I left just three weeks after the defamation law came in, so I haven’t felt the effect of it myself, and it’s been about a year since I’ve left the Maldives…But it’s really had a chilling effect. People are a lot more careful about what they report on and what they say. One of the television stations has been fined a number of times, and they’ve essentially had to set up donation boxes to collect the money to pay off these fines. And the law allows for the government to shut them down if they’re unable to pay the fines.

Tell me about the disappearance of your colleague, Ahmed Rilwan.

He was about 28, I think, when he disappeared. He was just a really wonderful human being, and he cared a lot about doing stories about rural Maldives, which is not covered very well by the local media. He also was quite a prominent blogger. He was quite prolific on social media before he joined our team. He was known for satirizing the religious extremists, and he received quite a lot of threats over the years…as did many other journalists.

For me, it was obviously one of the most important events of my life in some ways. Just to have someone you work with, you know, just to have them disappear like that. It was the first disappearance of that kind, and I think it made us all realize that it could happen again, and it did. In April one of Rilwan’s best friends [a political blogger] was killed as he came home from work.

What has it been like living in exile and working for Al Jazeera in Doha?

Al Jazeera has been really, really great. I think a lot of people who go into exile, it’s just this sense of having your moorings cut and not knowing what to do next. You know, to have this life and then just to be uprooted from it, to be away from your family and your daily routine and your job and everything that gave you meaning. It’s very jarring in many ways…it really impacts your sense of both identity and also…what gives you purpose and meaning in life. Suddenly all of that is taken away.

Do you think you will return to the Maldives one day?

I do hope to return to the Maldives one day. I think the hardest part about living in exile has been missing deaths and births. My grandmother died last December, and then I just add[ed] a baby niece, so I’d like to go back and see her.

When you return to the Maldives, do you think you will continue being a journalist?

Not for a little while I guess, and it depends on what happens in the Maldives. It will be really hard to go back and do exactly the same thing I was doing without persecution. I think if I were to go back and continue doing the same job, it’s just a matter of time before I’m picked up again.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/tOxGaGKy6fo”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”6″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”2″ element_width=”12″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1516806129189-84da7a6a-de56-3″ taxonomies=”9028″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Maldives Independent’s former editor Zaheena Rasheed and KRIK editor-in-chief Stevan Dojcinovic. (Photo: KRIK)

Thousands of miles separate the Maldives from Serbia, but Zaheena Rasheed, the Index award-winning journalist and former editor of Maldives Independent, and Stevan Dojcinovic, editor-in-chief of the Serbian investigative website KRIK, but both described similar attacks on press freedom at a panel discussion at the Corinthia Hotel in London.

Rasheed lives in exile, having been forced to flee the Indian Ocean archipelago after working on an Al Jazeera documentary critical of the Maldivian government. She said she escaped just in time – a man who left a day later “barely made it out of the airport”.

Rasheed spoke of the intimidation tactics that independent news media had been subject to in the country. “Some newsrooms had gangs going inside of the newsroom and saying specifically we are not leaving until certain articles were taken down,” she said.

The Maldivian government claims that these gangs are criminals beyond their control.

As violence does not deter outlets like Maldives Independent from their investigative work, president Abdulla Yameen’s regime resorted to legal means, including imposing a draconian defamation law.

Rasheed said: “The definition of defamation is so broad that I could be sued for something I think, it doesn’t have to even be expressed. It could be a gesture. If it’s a gang or criminals after you, you can hide and avoid it, but when it’s the government you just can’t.”

On Serbia, Dojcinovic said that most in the West do not realise the extent of the country’s problems. “There’s not a real, clear picture of Serbia in the EU regarding how wild corruption and crime are,” he said.

Both journalists have seen hard-won democratic freedoms erode quickly. In Serbia this slide began in 2012 when Aleksandar Vučić was elected prime minister (this month, Vučić was also elected as the country’s president). Dojcinovic said: “The government has managed to destroy and undermine all of the democratic institutions built over 12 years within two years. We no longer have an independent judicial system and it’s the same with the media.”

In the Maldives, 2012 also left its mark. “Since the coup, a lot of democratic gains have been lost. What we saw in the first couple of years after the coup were physical assaults against journalists,” Rasheed said. “There were murder attempts, death threats and one TV station was even torched.”

She said that police turned a blind eye to these attacks. “All of the CCTV cameras were turned away from the building. The police just weren’t there.”

Whilst the threats are different in Serbia, Dojcinovic described a choked media landscape: “It’s not possible to see criticism of the government in the mainstream media. Not on any newsstand or on any TV frequency. They have destroyed all of these institutions.”

Dojcinovic said that the Serbian government is falling into the same patterns as Slobodan Milosevic’s regime: “It’s the arrests of journalists by the same group of people who were behind the murder of journalists back in the 1990s. They can’t cross this line now because it would ruin their reputation with the EU, so they find a way to make your life a nightmare without leaving fingerprints.”

Reprisals for his work have included three smear campaigns: he has been tagged as a criminal for his links to organised crime, branded a foreign agent, and had his personal life put on display.

“You cannot fight this much either because you can only publish on the internet,” Dojcinovic said. “That’s nothing compared to the newspapers which present us in this way.”

In the Maldives, however, there appears to be no such line. Rasheed said: “A member of our team was disappeared in 2014. Then a well-known gangster, who we think was involved in our colleague’s disappearance, vandalised the security cameras [at our office] and left a machete at our door. And then I got a text message saying: ‘You’re next.’”

Rasheed thinks that her colleague Ahmed Rilwan was targeted because he was seen to be in favour of secularism, and negative stories about Islamic radicalisation raise the government’s ire. “What really bothers them are these stories of growing radicalisation in the Maldives because that is what puts tourists off,” she said.

Rasheed also spoke about the difficulties of constantly fighting such repression. She told the audience that she had, to some extent, been traumatised by her experiences. However: “As a journalist, the most important thing to do is to live to tell the story.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1492769899588-d49a7ccf-cd47-5″ taxonomies=”8148, 9028, 8734″][/vc_column][/vc_row]