Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

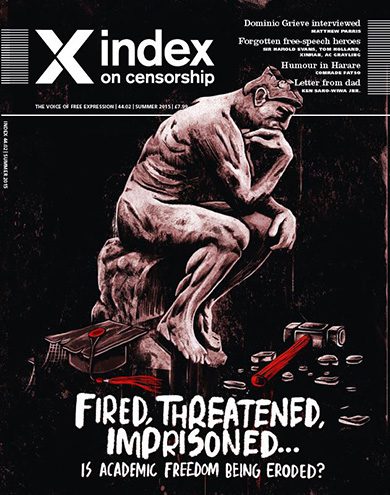

The summer 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine focusing on academic freedom will be available from 12 June.

With threats ranging from “no-platforming” controversial speakers, to governments trying to suppress critical voices, and corporate controls on research funding, academics and writers from across the world have signed Index on Censorship’s open letter on why academic freedom needs urgent protection.

Academic freedom is the theme of a special report in the summer issue of Index on Censorship magazine, featuring a series of case studies and research, including stories of how setting an exam question in Turkey led to death threats for one professor, to lecturers in Ukraine having to prove their patriotism to a committee, and state forces storming universities in Mexico. It also looks at how fears of offence and extremism are being used to shut down debate in the UK and United States, with conferences being cancelled and “trigger warnings” proposed to flag potentially offensive content.

Signatories on the open letter include authors AC Grayling, Monica Ali, Kamila Shamsie and Julian Baggini; Jim Al-Khalili (University of Surrey), Sarah Churchwell (University of East Anglia), Thomas Docherty (University of Warwick), Michael Foley (Dublin Institute of Technology), Richard Sambrook (Cardiff University), Alan M. Dershowitz (Harvard Law School), Donald Downs (University of Wisconsin-Madison), Professor Glenn Reynolds (University of Tennessee), Adam Habib (vice chancellor, University of the Witwatersrand), Max Price (vice chancellor of University of Cape Town), Jean-Paul Marthoz (Université Catholique de Louvain), Esra Arsan (Istanbul Bilgi University) and Rossana Reguillo (ITESO University, Mexico).

The letter states:

We the undersigned believe that academic freedom is under threat across the world from Turkey to China to the USA. In Mexico academics face death threats, in Turkey they are being threatened for teaching areas of research that the government doesn’t agree with. We feel strongly that the freedom to study, research and debate issues from different perspectives is vital to growing the world’s knowledge and to our better understanding. Throughout history, the world’s universities have been places where people push the boundaries of knowledge, find out more, and make new discoveries. Without the freedom to study, research and teach, the world would be a poorer place. Not only would fewer discoveries be made, but we will lose understanding of our history, and our modern world. Academic freedom needs to be defended from government, commercial and religious pressure.

Index will also be hosting a debate in London, Silenced on Campus, on 1 July, with panellists including journalist Julie Bindel, Nicola Dandridge of Universities UK, and Greg Lukianoff, president and CEO of Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, US.

To attend for free, register here.

If you would like to add your name to the open letter, email [email protected]

A full list of signatories:

Professor Mike Adams, University of North Carolina, Wilmington, USA

Monica Ali, author

Lyell Asher, associate professor, Lewis & Clark College, USA

Professor Jim Al-Khalili OBE, University of Surrey, UK

Esra Arsan, associate professor, Istanbul Bilgi University, Turkey

Julian Baggini, author

Professor Mark Bauerlein, Emory University, USA

David S. Bernstein, publisher, USA

Robert Bionaz, associate professor, Chicago State University, USA

Susan Blackmore, visiting professor, University of Plymouth, UK

Professor Jan Blits, professor emeritus, University of Delaware, USA

Professor Enikö Bollobás, Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary

Professor Roberto Briceño-León, LACSO, Caracas, Venezuela

Simon Callow, actor

Professor Sarah Churchwell, University of East Anglia, UK

Professor Martin Conboy, University of Sheffield, UK

Professor Thomas Cushman, Wellesley College, USA

Professor Antoon De Baets, University of Groningen, Holland

Professor Alan M Dershowitz, Harvard Law School, USA

Rick Doblin, Association for Psychedelic Studies, USA

Professor Thomas Docherty, University of Warwick, UK

Professor Donald Downs, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA

Professor Alice Dreger, Northwestern University, USA

Michael Foley, lecturer, Dublin Institute of Technology, Ireland

Professor Tadhg Foley, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland

Nick Foster, programme director, University of Leicester, UK

Professor Chris Frost, Liverpool John Moores University, UK

AC Grayling, author

Professor Randi Gressgård, University of Bergen, Norway

Professor Adam Habib, vice-chancellor, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Professor Gerard Harbison, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Adam Hart Davis, author and academic, UK

Professor Jonathan Haidt, NYU-Stern School of Business, USA

John Earl Haynes, retired political historian, Washington, USA

Professor Gary Holden, New York University, USA

Professor Mickey Huff, Diablo Valley College, USA

Professor David G. Hoopes, California State University, USA

Philo Ikonya, poet

James Ivers, lecturer, Eastern Michigan University, USA

Rachael Jolley, editor, Index on Censorship

Lee Jones, senior lecturer, Queen Mary University of London, UK

Stephen Kershnar, distinguished teaching professor, State University of New York, Fredonia, USA

Professor Laura Kipnis, Northwestern University, USA

Ian Kilroy, lecturer, Dublin Institute of Technology, Ireland

Val Larsen, associate professor, James Madison University, USA

Wendy Law-Yone, author

Professor Michel Levi, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Ecuador

Professor John Wesley Lowery, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, USA

Greg Lukianoff, president and chief executive, Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (Fire), USA

Professor Tetyana Malyarenko, Donetsk State Management University, Ukraine

Ziyad Marar, global publishing director, Sage

Charlie Martin, editor PJ Media, UK

Jean-Paul Marthoz, senior lecturer, Université Catholique de Louvain, Belgium

Professor Alan Maryon-Davis, King’s College London, UK

John McAdams, associate professor, Marquette University, USA

Timothy McGuire, associate professor, Sam Houston State University, USA

Professor Tim McGettigan, Colorado State University, USA

Professor Lucia Melgar, professor in literature and gender studies, Mexico

Helmuth A. Niederle, writer and translator, Germany

Professor Michael G. Noll, Valdosta State University, USA

Undule Mwakasungula, human rights defender, Malawi

Maureen O’Connor, lecturer, University College Cork, Ireland

Professor Niamh O’Sullivan, curator of Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, and Quinnipiac University, Connecticut, USA

Behlül Özkan, associate professor, Marmara University, Turkey

Suhrith Parthasarathy, journalist, India

Professor Julian Petley, Brunel University, UK

Jammie Price, writer and former professor, Appalachian State University, USA

Max Price, vice-chancellor, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Clive Priddle, publisher, Public Affairs

Professor Rossana Reguillo, ITESO University, Mexico

Professor Glenn Reynolds, University of Tennessee College of Law, USA

Professor Matthew Rimmer, Queensland University of Technology, Australia

Professor Paul H. Rubin, Emory University, USA

Andrew Sabl, visiting professor, Yale University, USA

Alain Saint-Saëns, director,Universidad Del Norte, Paraguay

Professor Richard Sambrook, Cardiff University, UK

Luís António Santos, University of Minho, Portugal

Professor Francis Schmidt, Bergen Community College, USA

Albert Schram, vice chancellor/CEO, Papua New Guinea University of Technology

Victoria H F Scott, independent scholar, Canada

Kamila Shamsie, author

Harvey Silverglate, lawyer and writer, Massachusetts, USA

William Sjostrom, director and senior lecturer, University College Cork, Ireland

Suzanne Sisley, University of Arizona College of Medicine, USA

Chip Stewart, associate dean of the Bob Schieffer College of Communication, Texas Christian University, USA

Professor Nadine Strossen, New York Law School, USA

Professor Dawn Tawwater, Austin Community College, USA

Serhat Tanyolacar, visiting assistant professor, University of Iowa, USA

Professor John Tooby, University of California, USA

Meena Vari, Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore, India

Professor Leland Van den Daele, California Institute of Integral Studies, USA

Professor Eugene Volokh, UCLA School of Law, USA

Catherine Walsh, poet and teacher, Ireland

Christie Watson, author

Ray Wilson, author

Professor James Winter, University of Windsor, Canada

On World Press Freedom Day, 116 days after the attack at the office of the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo that left 11 dead and 12 wounded, we, the undersigned, reaffirm our commitment to defending the right to freedom of expression, even when that right is being used to express views that we and others may find difficult, or even offensive.

The Charlie Hebdo attack – a horrific reminder of the violence many journalists around the world face daily in the course of their work – provoked a series of worrying reactions across the globe.

In January, the office of the German daily Hamburger Morgenpost was firebombed following the paper’s publishing of several Charlie Hebdo images. In Turkey, journalists reported receiving death threats following their re-publishing of images taken from Charlie Hebdo. In February, a gunman apparently inspired by the attack in Paris, opened fire at a free expression event in Copenhagen; his target was a controversial Swedish cartoonist who had depicted the prophet Muhammad in his drawings.

A Turkish court blocked web pages that had carried images of Charlie Hebdo’s front cover; Russia’s communications watchdog warned six media outlets that publishing religious-themed cartoons “could be viewed as a violation of the laws on mass media and extremism”; Egypt’s president Abdel Fatah al-Sisi empowered the prime minister to ban any foreign publication deemed offensive to religion; the editor of the Kenyan newspaper The Star was summoned by the government’s media council, asked to explain his “unprofessional conduct” in publishing images of Charlie Hebdo, and his newspaper had to issue a public apology; Senegal banned Charlie Hebdo and other publications that re-printed its images; in India, Mumbai police used laws covering threats to public order and offensive content to block access to websites carrying Charlie Hebdo images. This list is far from exhaustive.

Perhaps the most long-reaching threats to freedom of expression have come from governments ostensibly motivated by security concerns. Following the attack on Charlie Hebdo, 11 interior ministers from European Union countries, including France, Britain and Germany, issued a statement in which they called on internet service providers to identify and remove online content “that aims to incite hatred and terror”. In the UK, despite the already gross intrusion of the British intelligence services into private data, Prime Minister David Cameron suggested that the country should go a step further and ban internet services that did not give the government the ability to monitor all encrypted chats and calls.

Index report: Europe’s journalists face growing climate of fear

This kind of governmental response is chilling because a particularly insidious threat to our right to free expression is self-censorship. In order to fully exercise the right to freedom of expression, individuals must be able to communicate without fear of intrusion by the state. Under international law, the right to freedom of expression also protects speech that some may find shocking, offensive or disturbing. Importantly, the right to freedom of expression means that those who feel offended also have the right to challenge others through free debate and open discussion, or through peaceful protest.

On World Press Freedom Day, we, the undersigned, call on all governments to:

• Uphold their international obligations to protect the rights of freedom of expression and information for all, especially journalists, writers, artists and human rights defenders to publish, write and speak freely;

• Promote a safe and enabling environment for those who exercise their right to freedom of expression, especially for journalists, artists and human rights defenders to perform their work without interference;

• Combat impunity for threats and violations aimed at journalists and others threatened for exercising their right to freedom of expression and ensure impartial, speedy, thorough, independent and effective investigations that bring masterminds behind attacks on journalists to justice, and ensure victims and their families have speedy access to appropriate remedies;

• Repeal legislation which restricts the right to legitimate freedom of expression, especially such as vague and overbroad national security, sedition, blasphemy and criminal defamation laws and other legislation used to imprison, harass and silence journalists and others exercising free expression;

• Promote voluntary self-regulation mechanisms, completely independent of governments, for print media;

• Ensure that the respect of human rights is at the heart of communication surveillance policy. Laws and legal standards governing communication surveillance must therefore be updated, strengthened and brought under legislative and judicial control. Any interference can only be justified if it is clearly defined by law, pursues a legitimate aim and is strictly necessary to the aim pursued.

PEN International

Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

Africa Freedom of Information Centre

Albanian Media Institute

Article19

Association of European Journalists

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Belarusian PEN

Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism

Cambodian Center for Human Rights

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

Centre for Independent Journalism – Malaysia

Danish PEN

Derechos Digitales

Egyptian Organization for Human Rights

English PEN

Ethical Journalism Initiative

Finnish PEN

Foro de Periodismo Argentino

Fundamedios – Andean Foundation for Media Observation and Study

Globe International Center

Guardian News Media Limited

Icelandic PEN

Index on Censorship

Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information

International Federation of Journalists

International Press Institute

International Publishers Association

Malawi PEN

Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance

Media Institute of Southern Africa

Media Rights Agenda

Media Watch

Mexico PEN

Norwegian PEN

Observatorio Latinoamericano para la Libertad de Expresión – OLA

Pacific Islands News Association

PEN Afrikaans

PEN American Center

PEN Catalan

PEN Lithuania

PEN Quebec

Russian PEN

San Miguel Allende PEN

PEN South Africa

Southeast Asian Press Alliance

Swedish PEN

Turkish PEN

Wales PEN Cymru

West African Journalists Association

World Press Freedom Committee

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

Croatia’s new criminal code has introduced “humiliation” as an offence — and it is already being put to use. Slavica Lukić, a journalist with newspaper Jutarnji list is likely to end up in court for writing that the Dean of the Faculty of Law in Osijek accepted a bribe. As Index reported earlier this week, via its censorship mapping tool mediafreedom.ushahidi.com: “For the court, it is of little importance that the information is correct – it is enough for the principal to state that he felt humbled by the publication of the news.”

These kinds of laws exist across the world, especially under the guise of protecting against insult. The problem, however, is that such laws often exist for the benefit of leaders and politicians. And even when they are more general, they can be very easily manipulated by those in positions of power to shut down and punish criticism. Below are some recent cases where just this has happened.

On 4 June this year, security forces in Tajikistan detained a 30-year-old man on charges of “insulting” the country’s president. According to local press, he was arrested after posting “slanderous” images and texts on Facebook.

Eight people were jailed in Iran in May, on charges including blasphemy and insulting the country’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on Facebook. They also were variously found guilty of propaganda against the ruling system and spreading lies.

Also in May this year, Goa man Devu Chodankar was investigated by police for posting criticism of new Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Facebook. The incident was reported the police someone close to Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), under several different pieces of legislation. One makes it s “a punishable offence to send messages that are offensive, false or created for the purpose of causing annoyance or inconvenience”.

Human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko and journalist and editor Bheki Makhubu were arrested in March this year, and face charges of “scandalising the judiciary” and “contempt of court”. The charges are based on two articles, written by Maseko and Makhubu and published in the independent magazine the Nation, which strongly criticised Swaziland’s Chief Justice Michael Ramodibedi, levels of corruption and the lack of impartiality in the country’s judicial system.

In February this year, Venezuelan opposition leader Leopoldo Lopez was arrested on charges of inciting violence in the country’s ongoing anti-government protests. Human Rights Watch Americas Director Jose Miguel Vivanco said at the time that the government of President Nicholas Maduro had made no valid case against Lopez and merely justified his imprisonment through “insults and conspiracy theories.”

Student Honest Makasi was in November 2013 charged with insulting President Robert Mugabe. He allegedly called the president “a dog” and accused him of “failing to do what he promised during campaigns” and lying to the people. He appeared in court around the same time the country’s constitutional court criticised continued use of insult laws. And Makasi is not the only one to find himself in this position — since 2010, over 70 Zimbabweans have been charged for “undermining” the authority of the president.

In March 2013, Egypt’s public prosecutor, appointed by former President Mohamed Morsi, issued an arrest warrant for famous TV host and comedian Bassem Youssef, among others. The charges included “insulting Islam” and “belittling” the later ousted Morsi. The country’s regime might have changed since this incident, but Egyptian authorities’ chilling effect on free expression remains — Youssef recently announced the end of his wildly popular satire show.

A recent defamation law imposes hefty fines and prison sentences for anyone convicted of online slander or insults in Azerbaijan. In August 2013, a court prosecuted a former bank employee who had criticised the bank on Facebook. He was found guilty of libel and sentenced to 1-year public work, with 20% of his monthly salary also withheld.

In July 2013, a man was convicted and ordered to pay a fine or face nine month in prison, for calling Malawi’s President Joyce Banda “stupid” and a “failure”. Angry that his request for a new passport was denied by the department of immigration, Japhet Chirwa “blamed the government’s bureaucratic red tape on the ‘stupidity and failure’ of President Banda”. He was arrested shortly after.

While the penalties were softened somewhat in a 2009 amendment to the criminal code, libel remains a criminal offence in Poland. In September 2012, the creator of Antykomor.pl, a website satirising President Bronisław Komorowski, was “sentenced to 15 months of restricted liberty and 600 hours of community service for defaming the president”.

This article was published on June 6, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

By Paul Carlucci for Think Africa Press, an online magazine that offers commentary and in-depth analysis from leading African and international thinkers.

Lusaka, Zambia: A little over two years ago, when Michael Sata was campaigning for Zambia’s top office, he promised that, if elected, he would finally bring to an end a decade of abandoned legal reform and deliver the country a definitive new constitution. Not only that, but he would do it within 90 days of taking power.

Sata’s election campaign was successful, and soon after taking office in September 2011, the new president − along with his Patriotic Front (PF) government − tasked a committee of lawyers and academics with drafting the document.

Things soon slowed down however, and it is only now − several shrugged-off deadlines later − that Zambia seems to be nearing the completion of its constitutional process. Though that’s not to say things are necessarily moving smoothly. In December 2013, the government blocked the constitutional committee from releasing its final draft to the public, insisting it be sent to the government alone, while allegations have emerged that Sata has changed his mind about Zambia’s need for a new constitution, believing instead that the existing one can simply be amended.

The government has rejected these claims, asserting that Sata’s commitment to a new constitution remains “unshakeable”, and his two-year-old promise continues to loom large in the psyche of an increasingly outraged brigade of critics. After the 2014 budget revealed a skew of alarming numbers and the global rating agency Fitch downgraded the country’s credit rating, the PF’s economic success story lost its celebrated momentum, leaving it with little more than a narrative of heavy-handed autocracy.

Many of the government’s opponents have closed in on the constitution as a panacea for all that ails the country, a movement that culminated in a major demonstration at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross in Lusaka and which took a sensational twist on 15 January when the outspoken Zambian Watchdog published what it claims is a leak of the final draft.

A torrent of official statements followed as the drafting committee denied originating the leak, the police vowed to clamp down on what they termed a ‘cybercrime’, and the government vowed to track down and punish the perpetrators of the leak. The cabinet, which is meant to be deliberating the final draft, also claimed it hasn’t yet received its copies of the document.

While the authenticity of the leaked constitution is uncertain, it doesn’t stray far from the publicly available first draft, or even from previous drafts commissioned under past administrations. Zambia’s electoral system is addressed, requiring candidates to garner over 50% of the vote to hold presidential office, while parliament would be composed of members elected through a combination of first-past-the-post and proportional representation.

The draft Bill of Rights − which includes classical first generation rights as well as social, economic and cultural rights − is also more clearly articulated than it is in the existing constitution, and it seems to be these protections, more than technical changes to governance structure, that the opposition is longing for. They complain that their protests have been menaced by police and ruling party thugs, that critical media outlets have been persecuted by the government, and that the general population, especially outside the capital Lusaka, slogs through a life of poverty, illiteracy and environmental degradation.

Indeed, tackling these problems is crucial, but here’s the rub: there’s more than enough substance in the existing constitution to transform human rights in the country. That’s not the issue. The real problem is that successive administrations, including those headed by members of the now opposition Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD), simply cast off their legal responsibilities when it suits them. What needs to be tackled is Zambia’s tradition of impunity, which dates all the way back to the era of its independence president, Kenneth Kaunda.

When Zambia was granted independence in 1964, it started its new life with a multiparty framework, led by Kaunda’s United National Independence Party (UNIP), which had won 55 of 75 seats in the pre-independence elections. But this wasn’t to last. In 1972, keen outmanoeuvre political opponents both inside and outside the ruling party, Kaunda banned all political parties apart from UNIP. In 1973, he formalised one-party rule in a new constitution that also that consolidated state power in the president’s office.

It was only 18 years later when Zambia was choked by debt and was facing mounting pressure from the international community that Kaunda commissioned a hasty legal review. That move led to the establishment of the 1991 constitution and multiparty elections that brought MMD leader Fredrick Chiluba to power.

Not a lot has changed since then, despite the reform commissions that have been mandated, the reports that have been produced, and the many amendments proposed. One amendment that has been passed was a provision barring candidates with foreign parentage from running for the presidency. Chiluba, assisted by Sata, who was then a member of the MMD, managed to force through this provision in 1996, effectively blocking Kaunda, whose father was born in neighbouring Malawi, from returning. The amendment still exists today, but the kinds of reforms that would hold leaders more closely to account have remained elusive.

However, in many ways, the existing constitution does a lot of things right. It contains all the baseline requisites such as human dignity, equality before the law, protection from inhuman treatment, freedom from slavery, and freedoms of religion and expression. It also explicitly protects young people from various forms of exploitation. And under the Directive Principles of State Policy section, its clauses address employment, shelter, disability, and education. It does use some derogatory language, but so too do the current drafts of the new constitution.

The problem is that despite these legal mandates, correctional facilities are overcrowded and access to justice fails many prisoners in remand; there’s a long track record of beating, arresting, and criminally charging journalists, civil society leaders, and political figures who criticise government; poverty is endemic in rural areas, where education and healthcare facilities are also inadequate and the means of pursuing a gainful livelihood are largely absent.

When it comes to social and economic rights, many developing countries explain their failures in terms of cost. How can a poor nation like Zambia be expected to improve the lot of its direly undeveloped rural areas? How can it extend its meagre health and educational resources that far? How can it afford what human rights theorists call ‘positive rights’, those measures that require government action to protect and maintain?

Part of the answer is to dam the ever-bubbling backwaters of corruption, which divert enormous sums from the country’s development agenda. While corruption charges and trials do occur – usually motivated by political reasons – leaders from Chiluba to Sata have done little to substantively affect the diversion of public money from development to private bank accounts, while Chiluba in particular oversaw the country’s most notorious chapter of embezzlement.

In the short term, real change won’t emerge from the government’s legal apparatus. It will have to come from outside. Protesting Zambians have chalked up victories before, as when public demonstrations played a role in dissuading Chiluba from seeking an unconstitutional third term. And if NGOs, beleaguered though they are by looming registration reforms, were to focus their efforts on mobilising not just urban Zambians, but also those people living in undeveloped areas, more tangible results could be achieved.

But it’s not just a case of focusing their efforts. It’s a case of refocusing them. The fight for a new and improved constitution is certainly a worthy one, but civil society organisations have made a holy grail of constitutional reform, as if delivery will automatically slacken the state’s grip on an array of levers it freely abuses, from stacking the judiciary with supporters to deploying waves of violent thugs in by-election campaigns.

The current opposition, meanwhile, is only too pleased to ally itself with activists, but given the MMD’s own history of unjust governance, the teaming up is clearly for self-serving reasons. Rather than giving politicians such an elevated podium from which to reinvent themselves, civil society would do better to zero in on specific rights violations and protest those on the same scale as they do constitutional reform.

The other piece of this puzzle is the international community. That’s a difficult prescription for a continent whose leaders routinely play their populations against what they frame as foreign interference, but sustained pressure from multilateral organisations able to reference even the current set of constitutional guarantees would help consolidate demands made in the streets.

None of this is to say that robust laws can’t lay the groundwork for a future of mature, responsive governance. A strong legal framework, no matter its current irrelevance, will make for useful terms of reference in a more developed future, and human rights theorists habitually point to ambitious laws as key components to equitable progress. Indeed, what is a pie in the sky today could very well become steak on the plate tomorrow. The point is that it will take more than a good-looking tablecloth to make that happen.

Paul Carlucci is a Canadian writer and journalist based in Lusaka, Zambia. He has reported from Ghana and Ivory Coast for Think Africa Press, IPS Africa, Al Jazeera English, the Toronto Star, and the Toronto Standard. His collection of short stories ‘The Secret Life of Fission’ is available through Oberon Press. Follow him on twitter @PaulCarlucci.