28 Nov 2018 | Academic Freedom, Academic Freedom Reports, News and features, Press Releases

The full report can be read here.

A narrative of safety and risk is hampering freedom of speech on UK university campuses, a new report has found.

‘Uncomfortable but educational‘ — a short report and guide on the laws protecting free speech in universities by freedom of expression campaigners Index on Censorship — calls for more to be done to create an environment in which free speech is promoted as an equal good with other statutory duties. It also identifies Prevent as a key issue.

The report argues that universities should strengthen and simplify codes of practice to clarify their responsibilities and commitment to protecting free speech on campus. It also urges student unions to reaffirm a commitment to freedom of expression in their policies and remove “no-platforming” guidelines that involve outlawing speakers who are not members of groups already proscribed by government.

The report identifies the implementation of Prevent — which places obligations on universities to stop students being drawn into terrorism — as having a pernicious effect on freedom of expression and academic freedom in higher education and calls for an immediate independent review of the policy.

Despite near-daily news stories about attempts to shut down free speech on campus, the report finds that the environment for freedom of expression is poorly understood. Incidents are often misreported, while others — especially levels of self-censorship — are not reported publicly at all. A better understanding of the levels of explicit and implicit censorship on campus, coupled with the development of strategies for the better promotion of freedom of expression and at pre-university level are identified as crucial for ensuring free speech is protected.

The report draws on interviews and research of the sector over the past three years and in particular offers a guide to the legal protections and duties related to freedom of expression. It finds that often duties and rights such as those related to safety are presented as trumping those related to free speech, creating a risk-averse culture in which free speech is seen as a less important right.

“Protecting and promoting freedom of expression should be at the heart of what a university does – not an afterthought,” said Index on Censorship chief executive Jodie Ginsberg. “We want to encourage everyone to consider this as a core value – rather than one that is secondary to other rights and responsibilities.”

For more information or to arrange an interview, please contact Jodie Ginsberg at [email protected] or 020 7963 7260.

14 Jun 2016 | Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, India, Italy, mobile, News and features, Poland, United Kingdom

Timothy Garton Ash is no stranger to censorship. On the toilet wall of his Oxford home, there is a Polish censor’s verdict from early 1989 which cut a great chunk of text from an article of his on the bankruptcy of Soviet socialism.

Timothy Garton Ash is no stranger to censorship. On the toilet wall of his Oxford home, there is a Polish censor’s verdict from early 1989 which cut a great chunk of text from an article of his on the bankruptcy of Soviet socialism.

Six months later socialism was indeed bankrupt, although the formative experiences of travelling behind the Iron Curtain in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s — seeing friends such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn interrogated and locked up for what they published — never left him.

Now, in Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World, the professor of European Studies at Oxford University provides an argument for “why we need more and better free speech” and a blueprint for how we should go about it.

“The future of free speech is a decisive question for how we live together in a mixed up world where conventionally — because of mass migration and the internet — we are all becoming neighbours,” Garton Ash explains to Index on Censorship. “The book reflects a lot of the debates we’ve already been having on the Free Speech Debate website [the precursor to the book] as well as physically in places like India China, Egypt, Burma, Thailand, where I’ve personally gone to take forward these debates.”

Garton Ash began writing the book 10 years ago, shortly after the murder of Theo van Gough and the publication of the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons. In the second of the 10 principles of free speech — ranked in order of importance — he writes: “We neither make threats of violence nor accept violent intimidation.” What he calls the “assassin’s veto” — violence or the threat of violence as a response to expression — is, he tells Index, “one of the greatest threats to free speech in our time because it undoubtedly has a very wide chilling effect”.

While the veto may bring to mind the January 2015 killings at Charlie Hebdo, Garton Ash is quick to point out that “while a lot of these threats do come from violent Islamists, they also come from the Italian mafia, Hindu nationalists in India and many other groups”.

Europe, in particular, has “had far too much yielding, or often pre-emptively, to the threat of violence and intimidation”, explains Garton Ash, including the 2014 shutting down of Exhibit B, an art exhibition which featured black performers in chains, after protesters deemed it racist. “My view is that this is extremely worrying and we really have to hold the line,” he adds.

Similarly, in the sixth principle from the book — “one of the most controversial” — Garton Ash states: “We respect the believer but not necessarily the content of the belief.”

This principle makes the same point the philosopher Stephen Darwall made between “recognition respect” and “appraisal respect”. “Recognition respect is ‘I unconditionally respect your full dignity, equal human dignity and rights as an individual, as a believer including your right to hold that belief’,” explains Garton Ash. “But that doesn’t necessarily mean I have to give ‘appraisal respect’ to the content of your belief, which I may find to be, with some reason, incoherent nonsense.”

The best and many times only weapon we have against “incoherent nonsense” is knowledge (principle three: We allow no taboos against and seize every chance for the spread of knowledge). In Garton Ash’s view, there are two worrying developments in the field of knowledge in which taboos result in free speech being edged away.

“On the one hand, the government, with its extremely problematic counter-terror legislation, is trying to impose a prevent duty to disallow even non-violent extremism,” he says. “Non-violent extremists, in my view, include Karl Marx and Jesus Christ; some of the greatest thinkers in the history of mankind were non-violent extremists.”

“On the other hand, you have student-led demands of no platforming, safe spaces, trigger warnings and so on,” Garton Ash adds, referring to the rising trend on campuses of shutting down speech deemed offensive. “Universities should be places of maximum free speech because one of the core arguments for free speech is it helps you to seek out the truth.”

The title of the books mentions the “connected world”, or what is also referred to in the text as “cosmopolis”, a global space that is both geographic and virtual. In the ninth principle, “We defend the internet and other systems of communication against illegitimate encroachments by both public and private powers”, Garton Ash aims to protect free expression in this online realm.

“We’ve never been in a world like this before, where if something dreadful happens in Iceland it ends up causing harm in Singapore, or vice-versa,” he says. “With regards to the internet, you have to distinguish online governance from regulation and keep the basic architecture of the internet free, and that means — where possible — net neutrality.”

A book authored by a westerner in an “increasingly post-western” world clearly has its work cut out for it to convince people in non-western or partially-western countries, Garton Ash admits. “What we can’t do and shouldn’t do is what the West tended to do in the 1990s, and say ‘hey world, we’ve worked it out — we have all the answers’ and simply get out the kit of liberal democracy and free speech like something from Ikea,” he says. “If you go in there just preaching and lecturing, immediately the barriers go up and out comes postcolonial resistance.”

“But what we can do — and I try to do in the book — is to move forward a conversation about how it should be, and having looked at their own traditions, you will find people are quite keen to have the conversation because they’re trying to work it out themselves.”

28 Apr 2016 | Academic Freedom, Academic Freedom Reports, Campaigns -- Featured, mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

Academic freedom has been the subject of many debates in recent months. With speakers regularly being no-platformed, and increasing violations of safe space, universities and student unions across the UK have faced harsh criticism.

This growing trend of banning speakers from debates rather than confronting their views head on has led to calls for reforms in university policies in protecting academic freedom and so-called “safe space”.

When human rights activist and ex-Muslim Maryam Namazie was invited by the Atheist, Secularist and Humanist Society (ASH) to speak at Goldsmiths University in December 2015 she faced heckles and interruptions from students who opposed her views.

Throughout Namazie’s talk about blasphemy and apostasy members of Goldsmiths University’s Islamic Society (ISOC) caused a disruption by laughing, shouting out and even switching off her presentation, leading to some students being removed by security.

Namazie spoke to Index about the importance of academic freedom, stating: “Universities have always been hotbeds of dissent and progressive politics. They are places where anything can and should be discussed and debated – where deeply held sensibilities and beliefs can be reviewed, opposed and challenged.

“If you can’t express yourself on a university campus, doing so off-campus is usually even harder. Where academic freedom is restricted, it is a measure of the limits of free speech in society at large.”

Speaking about the Goldsmiths incident, Namazie refuses to be intimidated. She believes those pushing the Islamist narrative want to prevent a counter-narrative on university campuses and therefore it is more important for her to go and speak on any campus she is invited to and to push to be allowed where she is denied access.

“My family fled the Islamic regime of Iran in order to live freer lives. Therefore, it’s especially important for me to speak up, particularly given how many face imprisonment or lose their lives in doing so. I feel I have an added responsibility to speak for those who cannot,” she told Index.

In September 2015 Namazie was invited to speak at Warwick University by the Warwick Atheists, Secularists and Humanists’ Society, but her invitation was withdrawn by the University’s Student Union, who claimed her views would “incite hatred on campus”.

Other activists including Germaine Greer and Julie Bindel have also been silenced on campuses for their controversial views.

Namazie believes no-platforming is having a chilling effect on students’ academic freedom. She told Index: “These policies equate speech with real harm and violence though clearly there is a huge distinction between speech and action. Criticising Islam and Islamism, for example, is not the same as attacking Muslims. Nonetheless, I have been accused of ‘inciting violence’ or ‘inciting discrimination’ against Muslims.”

Human rights activist Peter Tatchell was involved in a dispute in February after National Union of Students’ LGBT representative Fran Cowling, declined to attend an event at the Canterbury Christ Church University at which Tatchell was giving a keynote address and participating on a panel.

He told Index: “Academic freedom is a crucial element of a free and open society. The right to explore, research, articulate, debate and contest ideas — even disagreeable ones — is a democratic hallmark.

“Imposing restrictions is the slippery slope to authoritarianism. As well as diminishing the realm of knowledge and understanding, it reinforces conformism and the status quo; putting a break on dissent and innovation.”

Right2Debate are a student-led movement who are campaigning for an end to censoring and no-platforming in universities by calling for student unions to reform their policies contesting rather than removing divisive and extremist narratives.

The movement, which has 100 student activists across 12 different UK universities and a further 3000 signatures of support, are aiming to have their four-point policy implemented by student unions across the UK. The policy’s outcomes include debate taking place over censorship, uncontested platforms for extremist speakers and transparency in the way the student unions conduct external speaker policy and challenging extremist/divisive narratives.

Haydar Zaki, Quilliam’s Outreach Right2Debate programme coordinator, told Index: “We are in this hostile environment to free speech because of the fruitless terms that have been employed at universities which include safe spaces and duty of care. In reality, these terms are completely open to interpretation, and have led to the chaos we see today whereby speakers are banned (or initially banned) at one university, but then freely allowed in others.

“What student unions and universities need to do is actually start implementing policies that are transparent and uniform — emphasising academic rights and the right to challenge over censorship.”

Bigoted ideas in society need challenging. To do so students require an academic environment that is willing to have open and civil discussions on all types of ideas, including those that could be deemed offensive, believes Benjamin David, an editor at Right2Debate.

Academic freedom is also essential for developing as a society, he told Index: “Academic freedom is important for a variety of reasons, none so pressing than the instrumental value that it has in making advancements in science, law or politics. Such advancements necessitate that the free discussion of opinion is available.”

The summer 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine which focuses on academic freedom. Subscribe here to get your copy.

Professor Chris Frost, former head of journalism at Liverpool John Moores University, agrees. Frost believes academic freedom is important for new ideas to be explored. He told Index: “Academic freedom is critical as it allows academics to investigate matters that may be generally considered socially unacceptable simply because there has been no previous investigation. We cannot expand knowledge and understanding if we don’t challenge socially accepted concepts and seek proof to support our theories. Preventing academic research leads to a stifled society and one that will eventually destroy itself through its own limitations.”

Academic freedom is a regular topic for debate for the Index on Censorship Youth Advisory Board, a group of young professionals who meet up for monthly online meetings to discuss current free speech issues. The board spoke to Index about why academic freedom is important to them.

Board member, freelance journalist and race, ethnicity and conflict Masters student, Layli Foroudi, told Index: “Academic freedom is important to me because the purpose of research and study should be to investigate reality, to seek to shed light on some aspect of life, or “truth” — and most importantly, to challenge other people’s truth claims. If there is no academic freedom then there will only be a narrow view of reality that is being purported and left unchallenged.”

Mark Crawford, a postgraduate student specialising in Russian and post-Soviet politics at University College London and current board member, added: “As a historian, it always seemed to me that academic freedom was the closest anyone can really get to ideas breaking down monopolies of power -– hard, scientific investigation can cut through the emotions around nationalism or religion, and afterwards you’re left with truths that however inconvenient are always extremely necessary for new and better narratives to be built.”

This article was updated on 3 May 2016. Corrects to clarify the nature of the dispute over Peter Tatchell’s appearance at Canterbury Christ Church University.

Josie Timms is editorial assistant at Index on Censorship and the first Liverpool John Moores University/Tim Hetherington fellow.

Related:

Why is freedom of speech important?

Worst countries for restrictions on religious freedom

17 Aug 2015 | mobile, News and features, United Kingdom, Youth Board

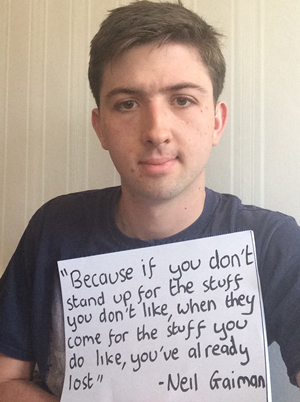

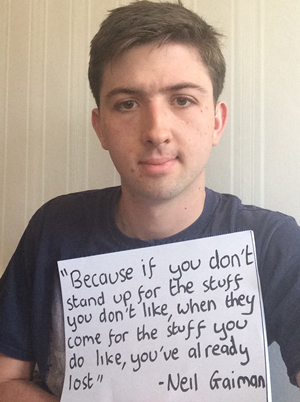

This is the second of a series of posts written by members of Index on Censorship’s youth advisory board.

Members of the board were asked to write a blog discussing one free speech issue in their country. The resulting posts exhibit a range of challenges to freedom of expression globally, from UK crackdowns on speakers in universities, to Indian criminal defamation law, to the South African Film Board’s newly published guidelines.

Tom Carter is a member of the Index youth advisory board. Learn more

Universities are meant to be institutions that embody the spirit of free expression. They are places where new ideas are formulated and environments where students are exposed to a range of viewpoints. However, whilst freedom of expression in universities is under threat from government intervention, another threat to freedom of expression on UK campuses is originating from the students themselves.

In October 2014, UKIP’s Nigel Farage was invited by the University of Cambridge’s politics department to give an address on an undisclosed topic. This prompted two independent Facebook campaigns, one of which was from the Cambridge University Students’ Union Women’s Campaign imploring Cambridge to rescind the invitation, which it eventually was.

This is indicative of an increasing hostility among UK students towards the expression of ideas deemed unacceptable. Whether or not you agree or disagree with UKIP’s policies, they are the UK’s third largest party by vote share and very much constitute part of the political mainstream.

The fact that students are now willing to influence the speaker choices of universities is a worrying trend. Only by hearing views different to your own can your ideas be refined and fine-tuned and hearing policies expressed in public discussion is the only way to scrutinise them effectively.

Tom Carter, UK

Related:

• Matthew Brown: Spying on NGOs a step too far

• About the Index on Censorship youth advisory board

• Facebook discussion: no-platforming of speakers at universities