25 Sep 2015 | Bahrain Statements, Campaigns, mobile, Statements

The Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, alongside 16 NGOs including Index on Censorship, today voiced support for the UN joint-statement on human rights in Bahrain. The statement, delivered by Switzerland at the 30th session of the UN Human Rights Council, was co-signed by 33 countries, including 19 EU states and the United States of America.

The statement remains open for additional signatories until the end of the Human Rights Council session on 2 October 2015. The NGOs invite states who have not signed to do so and call on those who have to continue exerting collective pressure for human rights progress in Bahrain.

Letter

To the Governments of: Albania, Argentina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Mexico, Republic of Korea, Serbia, Slovak Republic, and Spain

24 September 2015

Excellencies,

We, the undersigned non-governmental organisations, write to voice our support for the joint statement on the human rights situation in Bahrain delivered by Switzerland at the 30th Session of the Human Rights Council (HRC).

Since the last joint statement on Bahrain in June 2014, the government has continued to curtail the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly. Human rights defenders, political opposition leaders, members of the media, and youth have faced intimidation, arrest, arbitrary detention, unfair trials and acts of reprisal by the authorities. Furthermore, negotiations of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights’ (OHCHR) for a programme of technical capacity building in Bahrain have stalled in the period since the June 2014 joint statement.

We urge your government, therefore, to sign the joint statement on Bahrain delivered by Switzerland at the HRC’s 30th session in order to refocus international attention on human rights in Bahrain and encourage the government of Bahrain to constructively address its ongoing violations.

International pressure on Bahrain continues to assist in addressing human rights violations in Bahrain, as reflected by the decision of the King of Bahrain to release prominent human rights defender Nabeel Rajab under a royal pardon after he spent over four months in prison for a tweet criticising the government.

It is critical, therefore, to take action now to reaffirm the high level of international concern over human rights conditions in Bahrain. To abandon collective pressure on Bahrain at a time when the situation is continuing to deteriorate would send an entirely wrong message to the Bahraini government, and undermine both internal and external efforts to foster genuine reform.

Switzerland has indicated that this joint statement will be open for additional signatories throughout the session. We therefore call on your government to recommit to supporting human rights in Bahrain, and to add your endorsement to this joint statement.

Sincerely,

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

Amnesty International

ARTICLE 19

Bahrain Centre for Human Rights (BCHR)

Bahrain Institute of Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS)

CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation

English Pen

European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR)

European Centre for Democracy and Human Rights (ECDHR)

Human Rights Watch

Index on Censorship

International Service for Human Rights (ISHR)

Pen International

Rafto Foundation

The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

World Organization Against Torture (OMCT)

24 Sep 2015 | mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

Photograph: Marcos Mesa Sam Wordley

The shock general election result in May gave David Cameron licence to lay out his vision for Britain in the first Conservative Queen’s Speech for almost 20 years. Gone were the concessions to the Liberal Democrats of five years previous, and instead the key planks of the Conservative manifesto were there in full. Expected measures to cut the deficit, reform welfare and introduce an in/out EU referendum were all announced. But, according to many, another common thread ran through the new government’s legislative programme: an assault on free speech.

“We’re deeply concerned that the government says one thing – that it believes freedom of expression is a fundamental British value – but in practice doesn’t believe that and is introducing legislation that could have quite a severe impact on freedom of expression,” says Jodie Ginsberg, chief executive of Index on Censorship, which campaigns against attacks on free speech across the globe.

Critics of the Conservatives’ record on civil liberties point to the resurrection of plans that were sidelined during the last Parliament, largely because of Lib Dem intervention. Privacy activists are alarmed that the new Investigatory Powers Bill may represent the revival of the so-called snoopers charter, allowing the security services access to everyone’s online and social media records. Plans to abolish the Human Rights Act and replace it with a British Bill of Rights have been delayed.

But proposals that have free speech campaigners up in arms are being introduced over the coming months. The Extremism Bill will introduce new banning and extremism disruption orders, giving the home secretary and other agencies the power to intervene against suspected extremist groups, and strengthen Ofcom’s role in tackling broadcasters who transmit extremist content.

Introducing it in May, the Prime Minister said: “For too long, we have been a passively tolerant society, saying to our citizens: as long as you obey the law, we will leave you alone.”

The bill is part of the government’s five-year counter-extremism strategy to combat Islamist extremism and the increasing number of Britons travelling abroad to fight for Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (Isis). A key component of this strategy will be challenging those who promote “non-violent extremism”, said David Cameron in a wide-ranging July speech.

He said: “This means confronting groups and organisations that may not advocate violence – but which do promote other parts of the extremist narrative.

“We’ve got to show that if you say ‘yes, I condemn terror, but the kuffar are inferior’, or ‘violence in London isn’t justified, but suicide bombs in Israel are a different matter’ then you too are part of the problem.” He added that simply condemning Isis atrocities was insufficient, and that “we must demand that people also condemn the wild conspiracy theories, the anti-Semitism, and the sectarianism too”.

A lack of clarity on how the government will define what constitutes non-violent extremism has caused alarm among many in the Muslim community. Dr Shuja Shafi, secretary general of the Muslim Council of Britain, said there was concern that the strategy would “set new litmus tests which may brand us all as extremists, even though we uphold and celebrate the rule of law, democracy and rights for all”.

“The Prime Minister hasn’t given concrete proposals. The home secretary was asked to define extremism and she wasn’t able to do that,” says Mohammed Shafiq, chief executive of the Ramadhan Foundation, a Muslim welfare organisation.

Shafiq questioned which views would be considered beyond the pale. “If, for example, you say you believe in sharia law the Prime Minister is suggesting that will make you an extremist and you could potentially face infringement of your civil liberties by expressing those views. It could be a Muslim who says he opposes gay marriage. Does that make him a bigot? I think it’s a really dangerous erosion of civil liberties.

“My approach is very simple – if you believe in freedom of speech as I do, then the likes of Anjem Choudary, Tommy Robinson and other far-right leaders have the right to express their views, and equally we have the right to challenge, debate and expose them.

“But you don’t defeat extremism by taking away an individual’s ability to put their view across.”

In the speech, Cameron said the ideology that underpins Islamist extremism must be countered by “British values”, such as democracy and the rule of law.

But Ginsberg agrees that having such broad definitions of “acceptable” speech means that it is impossible to know what could be deemed extremist. “[Cameron] has talked very vaguely about British values but does that mean that anyone who questions the current voting system, for example, or the current political set up is being un-British? Or says that they favour anarchy even if they’re not actively advocating violence. Is that unacceptable?

“What’s fundamental about democracy is that you should be able to ask questions and to express views that sometimes will conflict with the prevailing political thinking.”

Other upcoming legislation is also causing alarm to free speech campaigners. The Trade Union Bill has been described as the most radical package of union reforms since the 1980s and dramatically alters how industrial action is called for and carried out. The bill would introduce a turnout threshold of 50 per cent on strike ballots, a 14-day notice period on strikes, allows employers to bring in agency workers to replace striking staff and outlines new regulations on picketing to prevent “intimidation” of non-strikers. It has been bitterly opposed by unions and the Labour Party.

But one small line in an accompanying consultation document to the bill has drawn particular gasps of astonishment. It proposes that unions must inform employers and police 14 days ahead of strike action of any online or social media activity it plans to adopt and whether a loudspeaker or banners will be used on the picket line. Failure to comply could result in an enforcement order being served or a fine. “It would mean there are enormous levels of employer and political scrutiny of trade union protests, beyond what we think is the norm among modern democracies in the developed world.

The worry is that the package of measures in the bill taken together substantially undermine the basic democratic right to strike,” says Nicola Smith, head of economic and social affairs at the TUC.

Although ministers say that restrictions would not apply to individuals, labour groups say that employees who already have little legal protection will feel intimidated and less likely to publicly support strike action. Many also believe it would be unworkable.

“It will be impossible to police. Who can control Facebook or Twitter? Who will monitor that?” says Carolyn Jones, director of the Institute of Employment Rights, a labour movement thinktank. “If one stray person – who may not be in the union – if they send something out, does that mean the strike is then illegal? And then the union has got to run the very expensive, very-time consuming ballots because this is seen to be illegitimate.

“The threat is there – it’s intimidation. What happened to freedom of association? There are so many bits of international law that it would threaten to break. It’s madness – is it proportionate to the problem? No.”

Union concerns are shared by free speech campaigners. “It’s an attack on freedom of expression, it’s a potential attack on freedom of assembly… The idea that you might have to seek permission from government or that government might be vetting the kinds of people who can and can’t say things is extremely worrying,” says Ginsberg.

But the government defended the bill as a whole. A Department for Business, Innovation & Skills spokesperson says: “People have the right to know that the services on which they and their families rely will not be disrupted at short notice by strikes supported by a small proportion of union members.

“The ability to strike is important but it is only fair that there should be a balance between the interests of union members and the needs of people who depend on their services.”

Index on Censorship is to launch a campaign against the Extremism Bill, and unions are resisting the changes to strike laws. But campaigners are gloomy about the prospect of the government changing tack over the long-term and abandoning policies they believe infringe on free speech. “This has been the direction of travel for a long time,” says Ginsberg, particularly in relation to national security. “The problem is that there is only one direction that it’s going in and that’s to restrict further free expression. We’re not seeing any move back or any relaxation of the foot on the pedal.”

This article originally appeared on 23 September 2015 at Big Issue North.

24 Sep 2015 | mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

I have been away, with thankfully intermittent internet access limiting my access to top quality prime minister/pig-related punning, so apologies if you see your fantastic pun replicated here. Entirely unintentional.

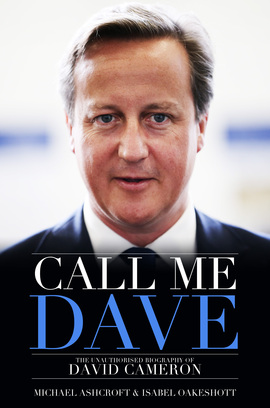

If you’ve been even more away than me, a quick recap of the story that will never die: Conservative peer Lord Ashscroft, he of the polls, has brought out a book — along with the Sunday Times’ Isabel Oakeshott — about Prime Minister David Cameron. Among the accusations levelled at Cameron are that Conservative colleagues see Libya as “his Iraq”, that he attempted to get a friend off criminal charges and that he listened to Supertramp.

No one cares about any of that stuff at all. The one thing everyone is, frankly, still cracking up about was the revelation in Monday’s Daily Mail (which is serialising the book) that Cameron, while at university, took part in an initiation ceremony for a drinking club which involved putting the parts of a prime minister we shouldn’t think about in a pig’s head. The head, it should be noted, was not attached to a live animal.

This is obviously enormously odd, and hilarious. I’m not about to get po-faced about sexual deviance, or how Cameron is screwing the country even more than he did that pig head, or, as I have seen, ponder the dark occult symbolism of our elite universities. Because, really, it’s not symbolic of anything apart from students being utter, utter clowns.

That is, of course, assuming that it is true. Something that is by no means certain. The source for the allegation is apparently an Oxford contemporary of Cameron’s who is now an MP, who reckons he has seen a photograph of a compromised future prime minister engaging with the hog’s head.

Now, “a bloke I know reckons he saw a photo” may be a decent threshold of proof for a pub anecdote (bonus points if the bloke is upgraded from mere bloke to “my brother’s friend” lending a real tangibility): but this is not presented as a pub anecdote, and as a presentation of proof, it doesn’t really do: it would never stand up in court, as the pig said to the aspiring Piers Gaveston member.

Given that, should David Cameron sue? Tricky business. Fine things that our new libel laws now are, does one really want a court case hinging on whether or not one performed indecencies on swine flesh a lifetime ago? Even if you win, do you want to go down in history as the Prime Minister who definitely didn’t have sex with a dead pig? One may as well buy a t-shirt with “not a wrong ‘un, honest” written on it.

In an interesting Guardian article, Damian McBride, a former spin doctor for Cameron’s predecessor Gordon Brown, wonders why Cameron’s people have not issued an official dismissal of “Piggate”, or any of the other allegation in the Ashcroft/Oakeshott book, pointing out that “In the absence of an instant bucket of water, the story has caught fire over the past two days. Not only that, it’s allowed other newspapers to declare open season on Cameron’s private life, as we see from today’s ‘coke parties’ splash in the Sun.”

I can understand McBride’s point, but I do think that Cameron’s people did the right thing here, mostly because if they start engaging with the specific allegations in the book, sooner or later they come round to having to confirm or deny the porcine partnering. We’re back to square one.

Where’s the free speech rub in this, I hear you ask? Well, there’s the simple fact that you have to be able to take as well as give in these matters. During Jeremy Corbyn’s ascendance to power as Labour leader, many of his followers complained daily of the outrageous “smears” of the dread MSM. In his leadership acceptance speech, Corbyn himself complained of the “most appalling levels of abuse from some of our media over the past three months” apparently suffered by him and his family during his campaign, which seemed to amount to some reheated speculation about the cause for a split from a previous partner and the shocking, shocking revelation that he ate baked beans out of a tin. Before you write in, questioning Corbyn’s public declarations and political associations is a necessary and important function of the press. People who complained about Corbyn’s apparent abuse now seem totally OK repeating allegations made by a wealthy Conservative peer in the pages of the Daily Mail. Which is fine, but just be aware of the mismatch. (To his credit, Corbyn appears to have entirely avoided the topic, though Cameron was lucky that there was no PMQs this week due to conference season).

Public figures will be open to scorn, ridicule, abuse and more. Their every move, from even before they aspired to power, will be pored over for clues and significance (as has been done by, for example, the New Statesman’s Laurie Penny with Cameron’s curious incident avec le cochon). It may happen, as we grow into an age where no one is embarrassable anymore, because they’ve already put everything on Instagram, that these stories will no longer make any sense. But for now they still happen, and on balance, it is good that they do.

When it comes to public figures, we should err away from caution. The extremely wealthy Ashcroft’s intervention with this string of what the KGB used to call Kompromat against Cameron is not perhaps the best example of the old speak-truth-to-power schtick (it’s more power calling other power names because it didn’t get what it wanted — a cabinet post, allegedly), but nonetheless, being rude about powerful people is very important and even cathartic — ask any cartoonist.

The rush of schweinficker jokes may have done little more than lifted the autumn gloom, but it’s strangely satisfying that in a democracy we can openly mock our leaders, safe in the knowledge that whatever they do, they’ll only make it worse for themselves.

23 Sep 2015 | Magazine, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by Max Wind-Cowie on free speech in politics, taken from the winter 2014 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the Elections – live! session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

We are often, rightly, concerned about our politicians censoring us. The power of the state, combined with the obvious temptation to quiet criticism, is a constant threat to our freedom to speak. It’s important we watch our rulers closely and are alert to their machinations when it comes to our right to ridicule, attack and examine them. But here in the West, where, with the best will in the world, our politicians are somewhat lacking in the iron rod of tyranny most of the time, I’m beginning to wonder whether we may not have turned the tables on our politicians to the detriment of public discourse.

Let me give you an example. In the UK, once a year the major political parties pack up sticks and spend a week each in a corner of parochial England, or sometimes Scotland. The party conferences bring activists, ministers, lobbyists and journalists together for discussion and debate, or at least, that’s the idea. Inevitably these weird gatherings of Westminster insiders and the party faithful have become more sterilised over the years; the speeches are vetted, the members themselves are discouraged from attending, the husbandly patting of the wife’s stomach after the leader’s speech is expertly choreographed. But this year, all pretence that these events were a chance for the free expression of ideas and opinions was dropped.

Lord Freud, a charming and thoughtful – if politically naïve – Conservative minister in the UK, was caught committing an appalling crime. Asked a question of theoretical policy by an audience member at a fringe meeting, Freud gave an answer. “Yes,” he said, he could understand why enforcing the minimum wage might mean accidentally forcing those with physical and learning difficulties out of the work place. What Freud didn’t know was that he was being covertly recorded. Nor that his words would then be released at the moment of most critical, political damage to him and his party. Or, finally, that his attempt to answer the question put to him would result in the kind of social media outrage that is usually reserved for mass murderers and foreign dictators.

Why? He wasn’t announcing government policy. He was thinking aloud, throwing ideas around in a forum where political and philosophical debate are the name of the game, not drafting legislation. What’s more, the kind of policy upon which he was musing is the kind of policy that just a few short years before disability charities were punting themselves. So why the fuss?

It’s not solely an issue for British politics. Consider the case of Donald Rumsfeld. Now, there’s plenty about which to potentially disagree with the former US secretary of state for defense – from the principles of a just war to the logistics of fighting a successful conflict – but what is he most famous for? Talking about America’s ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, he thought aloud, saying “because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know.” The response? Derision, accompanied by the sense that in speaking thus Rumsfeld was somehow demonstrating the innate ignorance and stupidity of the administration he served. Never mind that, to me at least, his taxonomy of doubt makes perfect sense – the point is this: when a politician speaks in anything other than the smooth, scripted pap of the media relations machine they are wont to be crucified on a cross of either outrage, mockery or both. Why? Because we don’t allow our politicians to muse any longer. We expect them to present us with well-polished packages of pre-spun, offence-free, fully-formed answers packed with the kind of delusional certainty we now demand of our rulers. Any deviation – be it a “U-turn”, an “I don’t know” or a “maybe” – is punished mercilessly by the media mob and the social media censors that now drive 24-hour news coverage.

Let me be clear about what I don’t mean. I am not upset about “political correctness” – or manners, as those of us with any would call it – and I am not angry that people object to ideas and policies with which they disagree. I am worried that as we close down the avenues for discussion, debate and indeed for dissent if we box our politicians in whenever they try to consider options in public – not by arguing but by howling with outrage and demanding their head – then we will exacerbate two worrying trends in our politics.

First, the consensus will be arrived at in safe spaces, behind closed doors. Politicians will speak only to other politicians until they are certain of themselves and of their “line- to-take”. They will present themselves ever more blandly and ever less honestly to the public and the notion that our ruling class is homogenous, boring and cowardly will grow still further.

Which leads us to a second, interrelated consequence – the rise of the taboo-breaker. Men – and it is, for the most part, men – such as Nigel Farage and Russell Brand in the UK, Beppe Grillo in Italy, Jon Gnarr in Iceland, storm to power on their supposed daringness. They say what other politicians will not say and the relief that they supply to that portion of the population who find the tedium of our politics both unbearable and offensive is palpable. It is only a veneer of radicalism, of course – built often from a hodge-podge of fringe beliefs and personal vanity – but the willingness to break the rules captures the imagination and renders scrutiny impotent. Where there are no ideas to be debated the clown is the most interesting man in the room.

They say we get the politicians we deserve. And when it comes to the twin plaques of modern politics you can see what they mean. On the one hand we sit, fingers hovering over keyboards, ready to express our disgust at the latest “gaffe” from a minister trying to think things through. On the other we complain about how boring, monotonous and uninspiring they all are, so vote for a populist to “make a point”. Who is to blame? We are. It is time to self-censor, to show some self-restraint, and to stop censoring our politicians into oblivion.

© Max Wind-Cowie and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas, featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the winter 2014 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.