11 Dec 2015 | Asia and Pacific, Campaigns, Malaysia, mobile, Statements

Dear Attorney General Mohamed Apandi Ali,

We write to you as organisations that are deeply concerned by the decision of the Malaysian authorities to prosecute Lena Hendry for her involvement in the screening of the award-winning human rights documentary, “No Fire Zone: The Killing Fields of Sri Lanka,” in Kuala Lumpur on July 9, 2013. The charges against her violate Malaysia’s obligations to respect the rights to freedom of opinion and expression, notably to receive and impart information. We respectfully urge you to drop the charges against Hendry. Her trial in Magistrate Court 6 in Kuala Lumpur is slated to begin on December 14, 2015.

As you know, Hendry is being charged under section 6 of the Film Censorship Act 2002, which imposes a mandatory prior censorship or licensing scheme on all films before they can be screened at any event, except films sponsored by the federal government or any state government. If convicted, she faces up to three years in prison and a fine up to RM 30,000.

The prosecution appears intended to restrict the activities of Hendry and members of the KOMAS, the human rights education and promotion organisation with which she works, by hindering their efforts to provide information and share their perspectives on human rights issues.

International human rights law and standards, such as found in article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, states that “everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

Malaysia has committed to ensuring that all human rights defenders are able to carry out their activities without any hindrance or fear of reprisals from the government. In November, Malaysia voted in favor of a resolution on “Recognizing the role of human rights defenders and the need for their protection” in the 3rd Committee of the United Nations General Assembly. The resolution set out the urgent need for governments to protect human rights defenders worldwide. Article 1 of the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, adopted unanimously by the UN General Assembly on December 9, 1998, states that “everyone has the right, individually and in association with others, to promote and to strive for the protection and realization of human rights and fundamental freedoms at the national and international levels.” Article 12(2) provides that the government shall “take all necessary measures to ensure the protection by the competent authorities of everyone, individually and in association with others, against any violence, threats, retaliation, de facto or de jure adverse discrimination, pressure or any other arbitrary action as a consequence of his or her legitimate exercise of his or her rights.”

In addition to dropping the charges against Hendry, we also urge you, as attorney general, to seek to repeal provisions of the Film Censorship Act 2002 that allow unnecessary and arbitrary government interference in the showing of films in Malaysia. This policy denies Malaysians the opportunity to benefit from a range of viewpoints on issues of importance to Malaysian society and that affect Malaysia’s role in the world.

Sincerely,

Brad Adams

Director, Asia Division

Human Rights Watch

Gail Davidson

Executive Director

Lawyers’ Rights Watch Canada

Jodie Ginsberg

Chief Executive

Index on Censorship

Karim Lahidji

President

International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

Mary Lawlor

Director

Front Line Defenders

Edgardo Legaspi

Executive Director

Southeast Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA)

Marie Manson

Program Director for Human Rights Defenders at Risk

Civil Rights Defenders

Champa Patel

Interim Director, South East Asia and Pacific Regional Office

Amnesty International

Amy Smith

Executive Director

Fortify Rights

Oliver Spencer

Head of Asia

Article 19

Gerald Staberock

Secretary General

World Organization Against Torture (OMCT)

Sam Zarifi

Regional Director for Asia and the Pacific

International Commission of Jurists

Cc:

Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, Minister of Home Affairs

Joseph Y. Yun, Ambassador of the United States of America to Malaysia

Luc Vandebon, Ambassador of the European Union to Malaysia

Victoria Treadell, British High Commissioner to Malaysia

Christophe Penot, Ambassador of France to Malaysia

Holger Michael, Ambassador of Germany to Malaysia

Rod Smith, Australian High Commissioner to Malaysia

Judith St. George Canadian High Commissioner to Malaysia

Dr John Subritzky, New Zealand High Commissioner to Malaysia

Ibrahim Sahib, Sri Lanka High Commissioner to Malaysia

16 Sep 2015 | Magazine

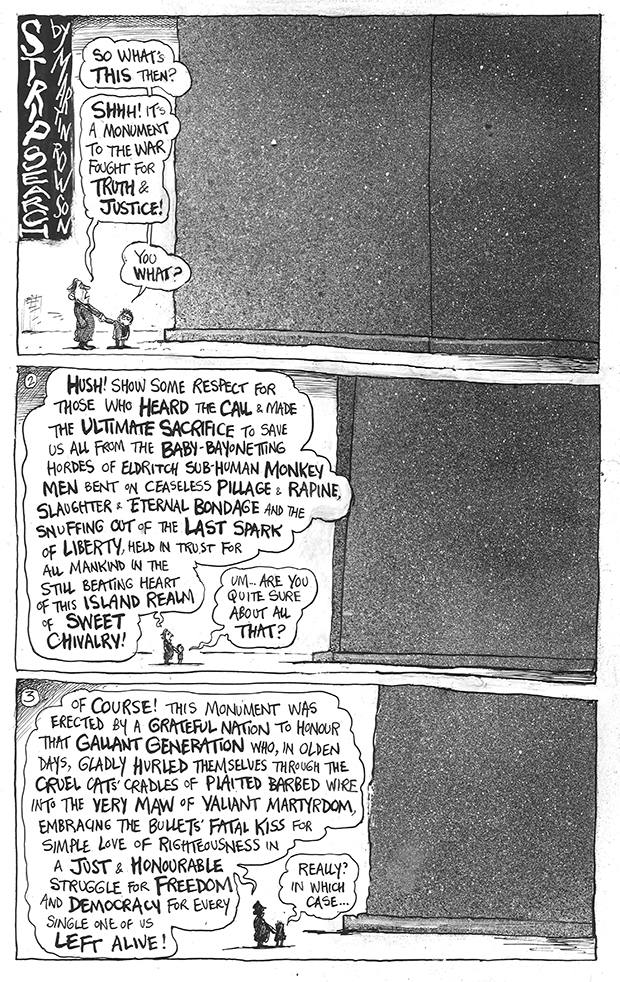

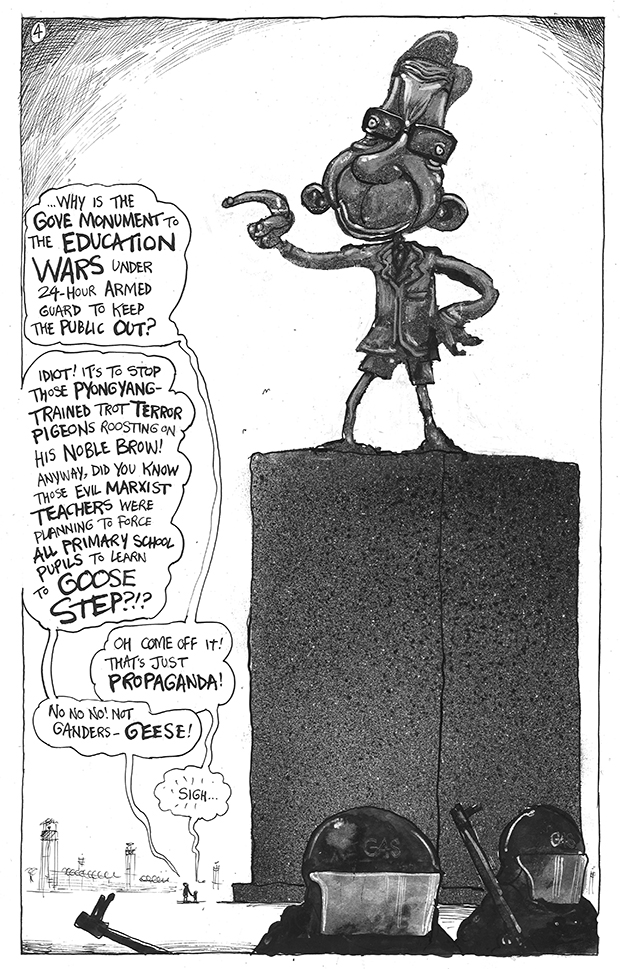

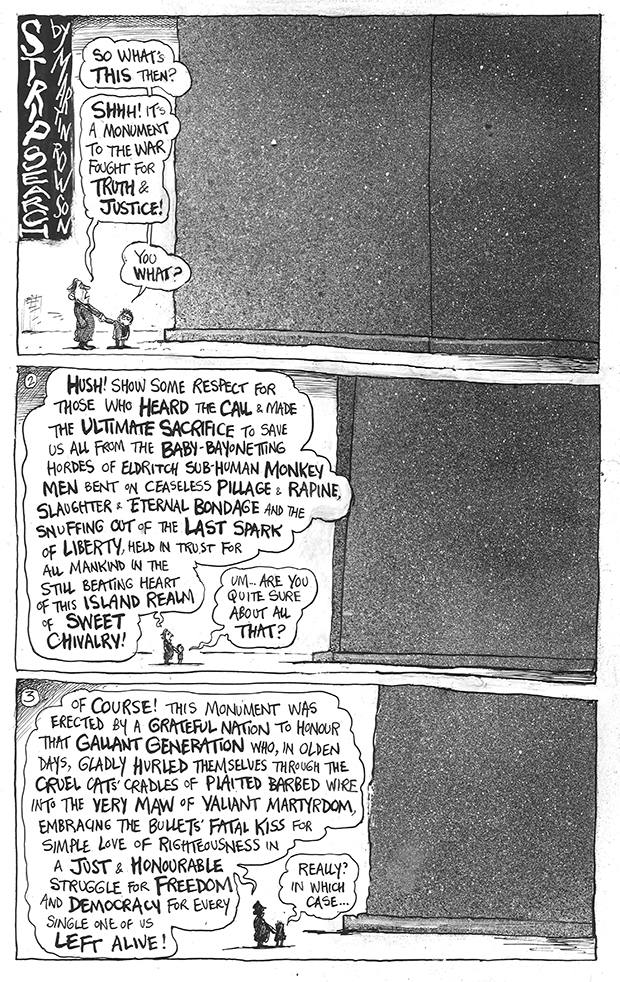

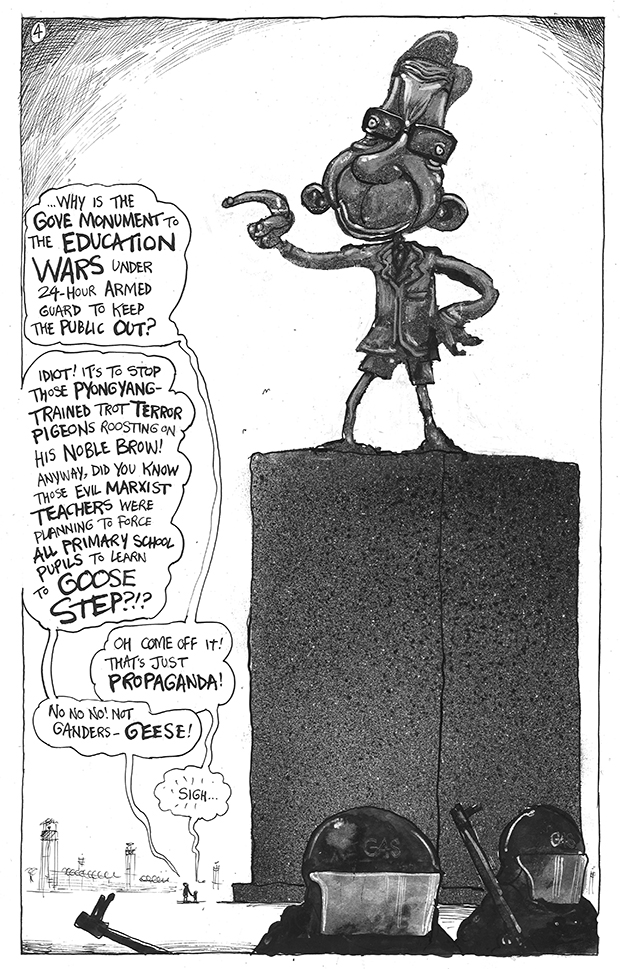

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by cartoonist and author Martin Rowson, who regularly draws for the magazine, on the power of propaganda in wartime, taken from the spring 2014 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the War, Censorship and Propaganda: Does It Work session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

As a political cartoonist, whenever I’m criticised for my work being unrelentingly negative, I usually point my accusers towards several eternal truths.

One is that cartoons, along with all other jokes, are by their nature knocking copy. It’s the negativity that makes them funny, because, at the heart of things, funny is how we cope with the bad – or negative – stuff.

Whether it’s laughing at shit, death or the misfortunes of others, without this hard-wired evolutionary survival mechanism that allows us to laugh at the awfulness running in parallel with being both alive and human, apes with brains the size of ours would go insane with existential terror as soon as the full implications of existence sink in. Which, for most people, would be when you’re around three years old.

And if that doesn’t persuade them, I usually then try to describe that indescribable but palpable transubstantiation that occurs when you shift from the negative to the positive, and a cartoon sinks from being satire to becoming propaganda.

Though here, of course, I’m not being entirely honest, because in many ways cartoons are propaganda in its purest form. This is because the methodology of the political cartoon has most in common with the practices of sympathetic magic and, likewise, its purposes are invariably malevolent.

Indeed, I’ve often described caricature in particular and political cartooning more generally as a type of voodoo, doing damage at a distance with a sharp object, in this case (usually) a pen.

Certainly the business of caricature is a kind of shamanist shape-shifting, distorting the appearance of the victim in order to bring them under the control of the cartoonist and subjecting them thereafter to ridicule or opprobrium. In short, political cartoons should truly be classified not as comedy but as visual taunts. And taunts, of course, have been an integral ingredient of warfare for millennia.

Within the twisted plaiting of taunts, posturing and brinkmanship that ultimately ended in the hecatombs of the Western Front in World War I you can just about tease out one thread trailing back to a cartoon.

The original sketch for the allegorical 1896 cartoon Nations of Europe: Join in Defence of Your Faith! was by Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, though he left the job of the finished artwork to professionals. Its purpose was to stiffen the resolve of European leaders against the “yellow peril” coming from east Asia, and to this end the Kaiser presented a copy of the cartoon to his cousin Tsar Nicholas II of Russia.

It’s generally agreed that the cartoon played a small but significant part in influencing the Tsar’s confrontational policy towards Japan, which ended in Russia’s humiliating defeat in the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese war.

The subsequent revolutions, regional wars and growing European instability erupted nine years later with the general mobilisation of the Great Powers, and the cartoonists were mobilised along with everyone else.

Although a perennial taunt against the Germans is that they have no sense of humour, they had as rich a tradition of visual satire as anyone else. In the pages of both Punch and the German satirical paper Simplicissimus, the enemy was caricatured identically as alternatively preposterous and terrifying. Both sides showed the other in league with skeletal personifications of Death, or transformed into fat clowns, foul or dangerous animals or, in British cartoons about Germans, as sausages.

There were also scores of cartoons showing German soldiers bayoneting Belgian babies in portrayals of “The Beastly Hun” and, later, cartoons showing the Germans harvesting the corpses of slain soldiers for fats to advance their war effort.

All sides taunted each other by attacking their nations’ supposed leaders, using the caricaturist’s typical tools. Thus the Kaiser, mostly thanks to his waxed moustache, acted as a synecdoche for Germany’s defining perfidy. In one cartoon from 1915, when Britain’s George V stripped his cousin, the Kaiser, of his Order of the Garter, his garterless stocking slips down, revealing a black and hairy simian leg. In 1914, meanwhile, the German cartoonist Arthur Johnson (his father was an American) showed the British Royal Family, German by descent, in a camp for enemy aliens.

These taunting cartoons bore little relation to the realities of modern warfare, and most of them would now be dismissed purely as rather ham-fisted propaganda. This shouldn’t downplay their effectiveness, however.

A century earlier Napoleon Bonaparte admitted he feared the damage done by James Gillray’s caricatures of him more than he feared any general, because Gillray always drew him as very short. (To bring this up to date, Le Monde’s cartoonist Plantu told me that every time he drew Nicolas Sarkozy as short, Sarkozy complained personally to his editor; the next cartoon would make him even shorter, and Sarkozy would complain again, until in the end Plantu drew the French president as just a head and feet.)

Nonetheless, an unforeseen consequence of this barrage of caricature was that in the end people stopped believing it to be anything more than merely caricature: the truth that should be exposed by the exaggeration got lost. In the 1930s, many people assumed reports of the genuine atrocities of the Nazis were, like the bayoneted babies or harvested corpses blamed on the Kaiser, just propaganda.

Posterity shouldn’t concern cartoonists. We’re just journalists responding to events with a raw immediacy. This is what gives the medium a great deal of its heft.

Some cartoons, however, encapsulate a time or an event and so become part of the more general visual language. Gillray’s The Plum Pudding in Danger is a perfect example, depicting the specific geopolitical struggle between William Pitt and Napoleon in 1805, while also capturing eternal truths about geopolitics itself. But I’m not aware of any political cartoons from World War I that do the same thing.

And yet the medium operates in many ways, and the most effective and popular cartoonist of World War I was undoubtedly Bruce Bainsfather, a serving artillery officer who drew gag cartoons about the slapstick of everyday life in the trenches in his series featuring “Old Bill”. The serving soldiers loved these cartoons, and they are another instance of humour being used to make the harshest imaginable reality simply bearable.

The other truly great cartoon to emerge from the World War I was published after it was all over. In his extraordinarily prophetic drawing Peace and Future Cannon Fodder for the Daily Herald, Will Dyson showed the Allied victors of the war exiting the Versailles peace conference and the French prime minister Georges Clemenceau saying: “Curious! I seem to hear a child weeping.” Behind a pillar a naked infant labelled “1940 class” is crying into its folded arms.

None of the protagonists in the next war doubted the power or importance of cartoons. Again, they were used by all sides to taunt and vilify their foes, perhaps most notoriously in Der Sturmer, the notorious anti-semitic paper edited by Julius Streicher, later hanged at Nuremburg.

Simplicissimus was, once more, taunting the British, this time drawing wartime prime minister, Winston Churchill, as a fat and murderous drunk; in the Soviet Union Stalin’s favourite cartoonist, Boris Yefimov, returned the compliment to the Nazi leadership (Yefimov’s older brother Mikhail first employed him on Pravda before being purged and executed in 1940; Boris survived him by 68 years, dying aged 108 in 2008). No cartoonist in either country would have dared caricature their own totalitarian politicians, but they were given full rein to exercise their skills on their nation’s enemies. In Britain, with its largely legally tolerated history of visual satire going back to 1695, things were slightly different, though also sometimes the same.

The New Zealand-born cartoonist David Low discovered in 1930 from a friend that Hitler, three years away from taking power in Germany, was an admirer of his work. Low did what any other cartoonist would do in similar circumstances and acknowledged his famous fan by sending him a signed piece of original artwork, inscribed “From one artist to another”.

It’s unknown what happened to the cartoon – maybe it was with him right to the end, in the bunker – but it soon became apparent that Hitler had mistaken Low’s attacks on democratic politicians for attacks on democracy itself. He was soon disabused. Low harried the Nazis all the way from the simple slapstick of The Difficulty of Shaking Hands with Gods of November 1933 to the bitterness of his iconic cartoon Rendezvous in September 1939, so much so that in 1936 British Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax, after a weekend’s shooting at Hermann Goering’s Bavarian hunting lodge, told Low’s proprietor at the Evening Standard, Lord Beaverbrook, to get the cartoonist to ease up as his work was seriously damaging good Anglo-German relations. Low responded by producing a composite cartoon dictator called “Muzzler”.

The Nazis had a point that Low entirely understood, and it was why he, along with many other cartoonists – Victor “Vicky” Weisz, Leslie Illingworth and even William Heath Robinson – were all on the Gestapo’s death list. In a debate on British government propaganda in 1943, a Tory MP said Low’s cartoon were worth all the official propaganda put together because Low portrayed the Nazis as “bloody fools”. Low himself later expanded on the point, comparing his work, which undermined the Nazis through mockery, with the work of pre-war Danish cartoonists who unanimously drew them as terrifying monsters. Low’s point was that it’s much easier to imagine you can beat a fool than a monster, and taunting your enemies as being unvanguishably frightening is no taunt at all.

The enduring efficacy of cartoons’ dark and magical voodoo powers were acknowledged in victory, when both Low and Yefimov were official court cartoonists at the Nuremburg war crimes tribunals (Low claimed Goering tried to outstare him from the dock): now the taunting was part of the humiliation served up with the revenge. Likewise, when Mussolini was executed by Italian partisans, the editor of the Evening Standard, Michael Foot, marked the dictator’s demise by giving over all eight pages of the paper to Low’s cartoons of Mussolini’s life and career.

Of course Low, unlike Yefimov, was actively hostile on the Home Front as well, producing cartoons critical of both the military establishment and Churchill. When Low’s famous creation Colonel Blimp, the portly cartoon manifestation of boneheaded reactionary thinking, took on fresh life in the Powell and Pressburger movie The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, Churchill tried to have the film banned. When the Daily Mirror’s cartoonist Philip Zec responded to stories about wartime profiteering by contrasting them with attacks on merchant shipping in his famous cartoon The Price of Petrol has Been Increased by One Penny – Official, both Churchill and Home Secretary Herbert Morrison seriously considered shutting down the newspaper. (When the Guardian cartoonist Les Gibbard pastiched Zec’s cartoon during the Falklands war 40 years later, the Sun called for him to be tried for treason.)

And yet cartoons, for all their voodoo power, can still spiral off into all sorts of different ambiguities thanks to the way they inhabit different spheres of intent. Are they there to make us laugh, or to destroy them? Or both?

Ronald Searle drew his experiences while he was a prisoner of war of the Japanese, certainly on pain of death had the drawings been discovered, but taking the risk in order to stand witness to his captors’ crimes. Just a few years later, many of his famous St Trinian’s cartoons don’t just deal with the same topics – cruelty and beheadings – but share identical composition with his prisoner of war drawings.

And when Carl Giles, creator of the famous cartoon family that mapped and reflected post-war British suburban life weekly in the Sunday Express, was present as an official war correspondent at the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, the camp’s commandant, Josef Kramer, revealed he was a huge fan of Giles’ work and gave him his pistol, a ceremonial dagger and his Nazi armband in exchange for the promise that Giles would send him a signed original. As Giles explained later, he failed to keep his part of the bargain because by the time he got demobbed Kramer had been hanged for crimes against humanity.

Those twinned qualities of taunting and laughter go some way to explaining the experience of cartoonists in the so-called war on terror, if not the power of their work. In the aftermath of 9/11, in the Babel of journalistic responses to what was without question the most visual event in human history, then visually re-repeated by the media that had initially reported it, the cartoonists were the ones who got it in the neck. While columnists wrote millions of words of comment and speculation, and images captured by machines were broadcast and published almost ceaselessly, the images produced via a human consciousness were, it seems, too much to stomach for many. Cartoonists had their work spiked, or were told to cover another story (there were no other stories). In the US some cartoonists had their copy moved to other parts of the paper, or were laid off. One or two even got a knock on the door in the middle of the night from the Feds under the provisions of the Patriot Act.

Despite a concerted effort by some American strip cartoonists to close ranks on Thanksgiving Day 2001 and show some patriotic backbone, the example of Beetle Bailey flying on the back of an American Eagle didn’t really act as a general unifier. Unlike in previous wars, there was no unanimity of purpose among cartoonists. An editorial in The Daily Telegraph accused me, along with Dave Brown of The Independent and The Guardian’s Steve Bell, of being “useful idiots” aiding the terrorist cause due to our failure to fall in line.

The war on terror and its Iraqi sideshow were anything but consensus wars, and many cartoonists articulated very loudly their misgivings. These included Peter Brookes of the Murdoch-owned Times drawing cartoons in direct opposition to his paper’s editorial line. This has always been one of visual satire’s greatest strengths: sometimes a cartoon can undermine itself.

Moreover, because a majority of cartoons were back in their comfort zone of oppositionism, the taunting had less of the whiff of propaganda about it. Nor was there ever any suggestion in Britain of government censorship of any of this.

That said, the volume of censuring increased exponentially, thanks entirely to the separate but simultaneous growth in digital communication and social media. Whereas, previously, cartoons might elicit an outraged letter to an editor – let alone a death threat from the Gestapo – the internet allowed a global audience to see material to which thousands of people responded, thanks to email, with concerted deluges of hate email and regular death threats. I long since learned to dismiss an email death threat as meaningless – a real one requires the commitment of finding my address, a stamp and possibly a body part of one of my loved ones – but it’s the thought that counts.

More to the point was the second front in the culture-struggle at the heart of the war on terror, in which both sides fought to take greater offence. Amid the bombs, bullets and piles of corpses across Iraq, Afghanistan, Bali, Madrid, London and all the other places, the greatest harm you could suffer, it seemed was that you might be “offended”. People sent me hate emails and threatened to kill me and my children because they were “offended” by my depiction of George Bush, or by a cartoon criticising Israel, or a stupid humourous drawing of anything that might mildly upset them or their beliefs.

It was into this atmosphere that the row over the cartoons of Mohammed published by the Danish newspaper Jyllands Posten erupted, resulting in the deaths of at least 100 people (none of them cartoonists, but most of them Muslims, and many shot dead by Muslim soldiers or policemen). But that, of course, is another story. And – who knows? – may yet prove to be another war.

Martin Rowson’s cartoons appear regularly in The Guardian and Index on Censorship. His books include The Dog Allusion, Giving Offence and Fuck: the Human Odyssey.

© Martin Rowson and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the spring 2014 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine, with a special report on propaganda and war. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

7 Aug 2015 | Campaigns, Europe and Central Asia, European Union, Germany, Statements

Update: German Federal Prosecutor drops treason probe of ‘Netzpolitik’ journalists, DW reported.

“The investigation against Netzpolitik.org for treason and their unknown sources is an attack against the free press. Charges of treason against journalists performing their essential work is a violation of the fifth article of the German constitution. We demand an end to the investigation into Netzpolitik.org and their unknown sources.”

Germany: Federal attorney general opens criminal charges against blog

“Die Ermittlungen gegen die Redaktion Netzpolitik.org und ihrer unbekannten Quellen wegen Landesverrats sind ein Angriff auf die Pressefreiheit. Klagen wegen Landesverrats gegen Journalisten, die lediglich ihrer für die Demokratie unverzichtbaren Arbeit nachgehen, stellen eine Verletzung von Artikel 5 Grundgesetz dar. Wir fordern die sofortige Einstellung der Ermittlungen gegen die Redakteure von Netzpolitik.org und ihrer Quellen.”

“Les charges contre Netzpolitik.org et leur source inconnue pour trahison sont une attaque contre la liberté de la presse. La poursuite pour trahison des journalistes qui effectuent un travail essentiel pour la démocratie est une violation du cinquième article de la constitution allemande. Nous demandons l’arrêt des poursites contre les journalistes de Netzpolitik.org et leurs sources.”

“La investigación en contra de Netzpolitik.org y su fuente por traición es un ataque a la libertad de la prensa. Acusaciones de traición a la patria hechas contra periodistas quienes estan realizando su labor esencial es una violacion del quinto artículo de la Constitución alemana. Exigimos que se detenga la investigación en contra de Netzpolitik.org y su fuente desconocida.”

Mahsa Alimardani, University of Amsterdam/Global Voices

Pierre Alonso, journalist, Libération

Sebastian Anthony, editor, Ars Technica UK

Jacob Appelbaum, independent investigative journalist

Jürgen Asbeck, KOMPASS

Julian Assange, editor-in-chief, WikiLeaks

Jennifer Baker, founder, Revolution News

Jennifer Baker (Brusselsgeek), EU correspondent, The Register

Diani Barreto, Courage Foundation

Mari Bastashevski, investigative researcher, journalist, artist

Carlos Enrique Bayo, editor-in-chief, PÚBLICO, Madrid, Spain

Sven Becker, journalist

Jürgen Berger, independent journalist

Patrick Beuth, journalist, Zeit Online

Ellery Roberts Biddle on behalf of Global Voices Advox

Florian Blaschke, blogger and managing editor, t3n.de

Eva Blum-Dumontet, Privacy International

Anne Bohlmann, freelance journalist

Detlef Borchers, freelance journalist, Heise

Stefan Buchen, journalist, NDR

Silke Burmester, journalist

Jan Böhmermann, late night TV host

Wolfgang Büchner, managing director Blick-Group, Switzerland / former

editor of DER SPIEGEL, Germany

Shawn Carrié, News & Politics editor, medium

David Carzon, deputy editor, Libération

Marina Catucci, journalist, Il Manifesto

Robin Celikates, associate professor of philosophy, University of Amsterdam

Graham Cluley, computer security and privacy columnist, grahamcluley.com

Gabriella Coleman, Wolfe Chair in Scientific and Technological Literacy,

McGill University

Josef Ohlsson Collentine, journalist, Pirate Times

Tommy Collison, opinion editor, Washington Square News

Ron Deibert, director, The Citizen Lab, Munk School of Global Affairs,

University of Toronto

Valie Djordjevic, publisher and editor of iRights.info

Daniel Drepper, senior reporter, CORRECT!V

Joshua Eaton, independent journalist

Matthias Eberl, multimedia journalist, Rufposten

Helke Ellersiek, NRW-Korrespondentin, taz.die tageszeitung

Carolin Emcke, journalist

Monika Ermert, freelance journalist

Anriette Esterhuysen, executive director, Association for Progressive

Communications

Cyrus Farivar, senior business editor, Ars Technica

Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai, journalist, Motherboard, VICE Media

Carola Frediani, journalist, Italy

Erin Gallagher, Revolution News

Sean Gallagher, Editor, Online and News, Index on Censorship

Johannes Gernert, journalist, TAZ

Aaron Gibson, freelance journalist and researcher

Dan Gillmor, author and teacher

John Goetz, investigative journalist, NDR/Süddeutsche Zeitung

Gabriel González Zorrilla, Deutsche Welle

Yael Grauer, freelance journalist

Glenn Greenwald, investigative journalist, The Intercept

Markus Grill, chief editor, CORRECT!V

Christian Grothoff, freelance journalist, The Intercept

Claudio Guarnieri, independent investigative journalist

Amaelle Guiton, journalist, Libération

Marie Gutbub, independent journalist

Nicky Hager, investigative journalist, New Zealand

Jessica Hannan, freelancer

Sarah Harrison, investigations editor, WikiLeaks

Martin Holland, editor heise online/c’t

Max Hoppenstedt, editor in chief, Vice Motherboard, Germany

Bethany Horne, journalist, Newsweek Magazine

Ulrich Hottelet, freelance journalist

Jérôme Hourdeaux, journalist, Mediapart

Johan Hufnagel, chief editor, Libération

Dr. Christian Humborg, CEO, CORRECT!V

Jörg Hunke, journalist

Mustafa İşitmez, columnist , jiyan.org

Eric Jarosinski, editor, Nein.Quarterly

Jeff Jarvis, professor, City University of New York, Graduate School of

Journalism

Cédric Jeanneret, EthACK

Simon Jockers, data journalist, CORRECT!V

Jörn Kabisch, journalist, Redaktion taz. am wochenende

Martin Kaul, journalist, TAZ

Nicolas Kayser-Bril, co-founder of Journalism++

Matt Kennard, Bertha fellow at the Centre for Investigative Journalism,

London

Dmytri Kleiner, Telekommunisten

Peter Kofod, freelance journalist, boardmember Veron.dk, Denmark

Joshua Kopstein, independent journalist, Al Jazeera America /

contributor, Motherboard / VICE

Till Kreutzer, publisher and editor of iRights.info

Jürgen Kuri, stellv. Chefredakteur, heise online/c’t

Damien Leloup, journalist, Le Monde

Aleks Lessmann, Bundespressesprecher, Neue Liberale

Daniel Luecking, online-journalist, Whistleblower-Network

Gavin MacFadyen, director for Center of Investigative Journalism and

professor at Goldsmiths University of London

Rebecca MacKinnon, journalist

Tanja Malle, ORF Radio Ö1

Dani Marinova, researcher, Hertie School of Governance, Berlin

Alexander J. Martin, The Register

Uwe H. Martin, photojournalist, Bombay Flying Club

Kerstin Mattys, freelance journalist

Stefania Maurizi, investigative journalist, l’ESPRESSO, Rome, Italy

Declan McCullagh, co-founder & CEO, Recent Media Inc

Derek Mead, editor, Motherboard (VICE Media)

Johannes Merkert, Heise c’t – Magazin für Computertechnik

Moritz Metz, reporter, Breitband, Deutschlandradio Kultur

Katharina Meyer, Wired Germany

Henrik Moltke, independent investigative journalist

Glyn Moody, journalist

Andy Mueller-Maguhn, freelance journalist

Erich Möchel, investigative journalist, ORF, Austria

Kevin O’Gorman, The Globe and Mail

Frederik Obermaier, investigative Journalist, Germany

Philipp Otto, publisher and editor of iRights.info

David Pachali, publisher and editor of iRights.info

Trevor Paglen, freelance journalist and artist, America

Michael Pereira, interactive editor, The Globe and Mail, Canada

Christian Persson, co-publisher of c’t magazine and Heise online

Angela Phillips, professor Department of Media and Communications,

Goldsmiths University of London

Edwy Plenel, president, Mediapart

Laura Poitras, investigative journalist, The Intercept

J.M. Porup, freelance journalist

Tim Pritlove, metaebene

Jeremias Radke, journalist, Heise, Mac & i

Jan Raehm, freelance journalist

Andreas Rasmussen, danish freelance journalist

Jonas Rest, editor, Berliner Zeitung

Georg Restle, redaktionsleiter, ARD Monitor

Frederik Richter, reporter, CORRECT!V

Jay Rosen, professor of journalism, New York University

Christa Roth, freelance journalist

Leif Ryge, independent investigative journalist

Ahmet A. Sabancı, journalist/writer, co-editor-in-chief and

Co-Spokesperson of Jiyan.org

Jonathan Sachse, reporter, CORRECT!V

Philip Di Salvo, researcher and journalist

Don Sambandaraksa, Southeast Asia Correspondent, TelecomAsia

Eric Scherer, director of future media, France Télévisions

Kai Schlieter, Reportage & Recherche, TAZ

Christian Schlüter, journalist, Berliner Zeitung

Marie Schmidt, journalist, Die Zeit

Bruce Schneier, security technologist and author

David Schraven, publisher, CORRECTIV

Daniel Schulz, Redaktion taz.am wochenende

Christiane Schulzki-Haddouti, independent journalist and researcher

Merlin Schumacher, editor in chief, for Zebrabutter

Clay Shirky, associate professor, NYU

Teresa Sickert, author and radio host

Christian Simon, editor, Social Media Watchblog

Claudia Simon, kultur propaganda, Berlin – www.kultur-propaganda.de

Mario Sixtus, Elektrischer Reporter

Michael Sontheimer, journalist, DER SPIEGEL

Efe Kerem Sozeri, journalist, Jiyan.org

Matthias Spielkamp, iRights.info, board member of Reporters without

Borders Germany, member of the advisory council of the Whistleblower

Netzwerk

Volker Steinhoff, Redaktionsleiter ARD Panorama

Andrea Steinsträter, journalist and editor at the news team of the WDR

Television

Catherine Stupp, freelance journalist

Batur Talu, media consultant, Istanbul

Trevor Timm, co-founder and executive director, Freedom of the Press

Foundation

Dimitri Tokmetzis, journalist, De Correspondent

Ilija Trojanow, journalist

Albrecht Ude, journalist

Martin Untersinger, journalist, Le Monde

Nadja Vancauwenberghe, editor-in-chief, EXBERLINER

Andreas Weck, journalist

Jochen Wegner, editor-in-chief, ZEIT ONLINE

Stefan Wehrmeyer, data journalist, CORRECTIV

Rob Wijnberg, founder, editor-in-cheif, De Correspondent

Jeroen Wollaars, correspondent for Germany and Central Europe, Dutch

public broadcaster NOS

Krystian Woznicki, berlinergazette.de

Maria Xynou, researcher, Tactical Tech

John Young, Cryptome

Juli Zeh, author

Christoph Zeiher, independent journalist

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

22 Dec 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, Magazine, News, Politics and Society, United Kingdom, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

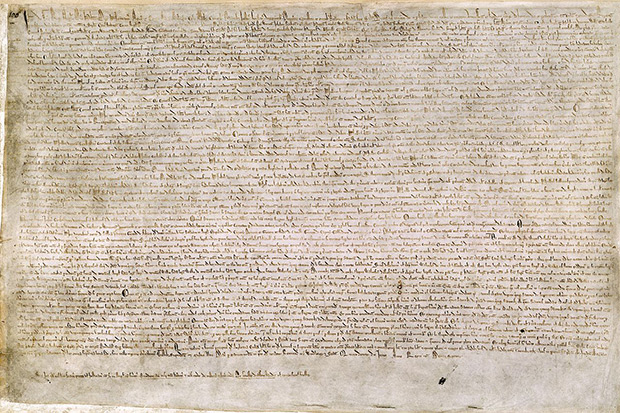

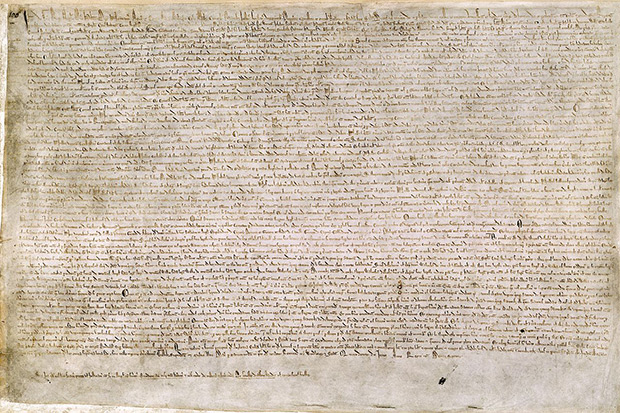

2015 marks the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta. Index on Censorship magazine’s winter issue has a special report that examines all ways in which the document affected modern freedoms. Here John Crace kicks us off with a tongue-in-cheek trip through history

Call it a free for all. Call it an innate sense of fair play. Call it what you will, but the English had always had a way of making their feelings known to a monarch who got a bit above himself by hitting the country for too much money in taxes or losing overseas military campaigns or both. They rebelled. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t but it was the closest medieval England had to due process. Then came John, a king every bit as unloved – if not more so – as any of his predecessors; a ruler who had gone back on many of his promises and was doing his best to lose all England’s French possessions and all of a sudden the barons had a problem. There wasn’t any obvious candidate to replace him.

So instead of deposing him, they took him on by limiting his powers.

Kings never have much liked being told what to do and John was no exception. If he could have got out of cutting a deal with the barons he would have done. But even he understood that impoverishing the people he relied on to keep him in power hadn’t been the cleverest of moves, and so he reluctantly agreed to take part in the negotiations that led to the sealing of The articles of the Barons – later known as Magna Carta – at Runnymede on 15 June 1215. Which isn’t to say he didn’t kick and scream his way through them before agreeing to the 61 demands which were the bare minimum for his remaining in power. He did, though, keep his fingers cunningly crossed when the seal was being applied. As soon as the barons had left London, King John announced — with the Pope’s blessing — that he was having no more to do with it. The barons were outraged and went into open rebellion, though dysentery got to King John before they did and he died the following year. Don’t shit with the people, or the people shit with you. Or something like that.

With the original Magna Carta having lasted barely three months, there were some who reckoned they could have saved themselves a lot of time and effort by topping King John rather than negotiating with him. But wiser – or perhaps, more peaceful – counsel prevailed and its spirit has endured through various subsequent mutations – most notably the 1216 Charter, The Great Charter of 1225 and the Confirmation of Charters of 1297 and has widely come to be seen as the foundation stone of constitutional law, both in England and many countries around the world. It was the first time limitations had been formally placed on a monarch’s power and the rights of citizens to the due process of law and trial by jury had been affirmed. Well, not quite all citizens. When the various charters talked of the rights of Freemen, it didn’t mean everyone; far from it. Freemen just meant that small class of people, below the barons, who weren’t tied to land as serfs. The Brits have never liked to rush things. They like their revolutions to be orderly. The underclass would just have to wait.

Magna Carta and its derivative charters were never quite the symbols of enlightened noblesse oblige they are often held to be. The noblemen didn’t sit around earnestly thinking about how they could turn England into a communal paradise. What was the point of having fought and back-stabbed your way to the top only to give power away to the undeserving? The charters were matters of political expedience. The nobles needed the Freemen on their side in their face-off with the king and an extension of their rights was the bargaining chip to secure it. Benevolence never really entered the equation. Nor was Magna Carta ever really a legal constitutional framework. Even if King John hadn’t decided to ignore it within months, it would still have been virtually unenforceable as it had no statutory authority. It was more wish-list than law.

Ironically, though, it is Magna Carta’s weaknesses that have turned out to have guaranteed its survival. Over the centuries, Magna Carta has become the symbol of freedom rather than its guarantor as different generations have cherry-picked its clauses and interpreted them in their own way. While wars and poverty might have been the prime catalyst for the Peasant’s Revolt against King Richard II in 1381, it was Magna Carta to which the rebellion looked for its intellectual legitimacy. The Freemen were now seen to be free men; constitutional rights were no longer seen as residing in the few. The King and his court were outraged that the peasants had made such an elementary mistake as to mistake the implied capital F in Freemen for a small f and the leaders were executed for their illiteracy as much as their impudence.

Bit by bit, starting in 1829 with the section dealing with offences against a person, the clauses of Magna Carta were repealed such that by 1960 only three still survived. Some, such as those concerning “scutage” — a tax that allowed knights to buy out of military service — and fish weirs, had become outdated; others had already been superseded by later statutes. Two of those that remained related to the privileges of both the Church of England and the City of London — a telling insight into the priorities of the establishment. Those who still wonder, following the global financial collapse of 2008, why the bankers were allowed to get away with making up the rules to suit themselves need look no further than Magna Carta. The bankers had been used to getting away with it for the best of 800 years. You win some you lose some.

The survival of clause 39 of the original Magna Carta has been rather more significant for the rest of us. “No Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the Land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right.” Or in layman’s terms, due process: the legal requirement of the state to recognise and respect all the legal rights of the individual. The guarantee of justice, fairness and liberty that not only underpins – well, most of the time – the UK’s constitutional framework, but those of many other countries as well.

Britain has no written constitution. Not because parliament has been too lazy to get round to drawing one up, but because one is already assumed to be in the lifeblood of every one living in Britain. Queen Mary may have had “Calais” written on her heart, but the rest of us all have “Magna Carta” inscribed there. It can be found on the inside of the left ventricle, for those of you who are interested in detail. Other countries haven’t been so trusting in the genetic inheritance of feudal England and have insisted on getting their constitutions down in non-fugitive ink.

That Magna Carta has also been the lodestone for the constitutions of so many other countries, most notably the USA, is less a sign of the global reach of democratic principles – much as that might resonate with romantic ideals of justice — than of the spread of British people and British imperial power. After the Mayflower arrived in what became the USA from Plymouth in 1620, the first settlers’ only reference point for the establishment of civil society was Magna Carta. The settlers had a lot of other things on their minds in the early years — most notably their own survival and the share price of British American Tobacco — and they hadn’t got time to dream up their own bespoke constitution. If they had, they might have come up with something that abolished slavery and gave equal rights to black people sometime before the 1960s. So they settled for an off-thepeg version of Magna Carta, with various US amendments. And some poor spelling. In 1687 William Penn published the first version of Magna Carta to be printed in America. By the time the fifth amendment — part of the bill of rights – was ratified four years after the original US constitution in 1791, Magna Carta had been enshrined in American law with “No person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.”

The fact that the American idea of Magna Carta was not one that would necessarily have been recognised in Britain was neither here nor there. For the Americans, the notion of the rights of a people to govern themselves was more than something that had been fought for over many centuries – a gradual taking back of power from an absolute ruler — that had been ratified on paper. They were fundamental rights that pre-existed any country and transcended national borders. And even if there was no one left alive on Earth, these rights would remain. They might as well have been handed down by God, though it’s probably just as well Adam hadn’t read the sections on the right to defend himself and bear arms. If he had shot the serpent, the whole history of the world might have been very different. As it is, when the Americans took on the British in the War of Independence, they weren’t fighting against a colonial overlord so much as for their basic rights to freedom.

The distinction is a subtle but important one. For though the more recent constitutions of former British colonies, such as Australia, India, Canada and New Zealand, more closely reflected the way Magna Carta was understood back in the mothership, those interpretations of it were still very much a product of their time. As a historical document, Magna Carta remains fixed in the 13th century: a practical solution to the problem of an iffy king. But as a concept it is a shifting, timeless expression of the democratic ideal. It can mean and explain anything. Up to and including that Britain always knows best.

Yet the appeal of Magna Carta endures and it remains the gold standard for democracy in any debate. Whatever side of it you happen to be on. British eurosceptics argue that the UK’s continuing membership of the European Union threatens the very parchment on which it was written; that Britain is being turned into a serf by a European despot. Pro Europeans argue that the EU does more than just enshrine the ideals of Magna Carta, it turns the most threatened elements of it into law.

Eight hundred years on, Magna Carta remains a moving target. Something to be aspired to but never truly attained. A highly combustible compound of idealism and pragmatism. Somehow, though, you can’t help feeling that King John and the feudal barons would have understood that. And approved.

This article is from the Winter 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine as 1215 and all that.

This article was originally posted on Dec 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org