7 Feb 2017 | Americas, Art and the Law, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements, United States

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Today, more than thirty cultural institutions and human rights organisations around the world, including international arts, curators’ and critics’ associations, organisations protecting free speech rights, as well as US based performance, arts and creative freedom organisations and alliances, issued a joint statement opposing United States President Donald J. Trump’s immigration ban. Read the full statement below.

On Friday, January 27th, President Trump signed an Executive Order to temporarily block citizens of seven predominantly Muslim countries from entering the United States. This order bars citizens of Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen from entering the United States for 90 days. It also suspends the entry of all refugees for 120 days and bars Syrian refugees indefinitely.

The organisations express grave concern that the Executive Order will have a broad and far-reaching impact on artists’ freedom of movement and, as a result, will seriously inhibit creative freedom, collaboration, and the free flow of ideas. US border regulations, the organisations argue, must only be issued after a process of deliberation which takes into account the impact such regulations would have on the core values of the country, on its cultural leadership, and on the world as a whole.

Representatives of several of the participating organisations issued additional statements on the immigration ban and its impact on writers and artists:

Helge Lunde, Executive Director of ICORN, said, “Freedom of movement is a fundamental right. Curtailing this puts vulnerable people, people at risk and those who speak out against dictators and aggressors, at an even greater risk.”

Svetlana Mintcheva, Director of Programs at the US National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC), said, “In a troubled and divided world, we need more understanding, not greater divisions. It is the voices of artists that help us understand, empathise, and see the common humanity underlying the separations of political and religious differences. Silencing these voices is not likely to make us any safer.”

Suzanne Nossel, Executive Director of PEN America, said, “The immigration ban is interfering with the ability of artists and creators to pursue their work and exercise their right to free expression. In keeping with its mission to defend open expression and foster the free flow of ideas between cultures and across borders, PEN America vows to fight on behalf of the artists affected by this Executive Order.”

Diana Ramarohetra, Project Manager of Arterial Network, said, “A limit on mobility and limits on freedom of expression has the reverse effect – to spur hate and ignorance. Artists from Somalia and Sudan play a crucial role in spreading the message to their peers about human rights, often putting themselves at great risk in countries affected by ongoing conflict. Denying them safety is to fail them in our obligation to protect and defend their rights.”

Ole Reitov, Executive Director of Freemuse, said, “This is a de-facto cultural boycott, not only preventing great artists from performing, but even negatively affecting the US cultural economy and its citizens rights to access important diversity of artistic expressions.”

Shawn Van Sluys, Director of Musagetes and ArtsEverywhere, said, “Musagetes/ArtsEverywhere stands in solidarity with all who protect artist rights and the freedom of mobility. It is time for bold collective actions to defend free and open inquiry around the world.”

A growing number of organisations continue to sign the statement.

JOINT STATEMENT REGARDING THE IMPACT OF THE US IMMIGRATION BAN ON ARTISTIC FREEDOM

Freedom of artistic expression is fundamental to a free and open society. Uninhibited creative expression catalyses social and political engagement, stimulates the exchange of ideas and opinions, and encourages cross-cultural understanding. It fosters empathy between individuals and communities, and challenges us to confront difficult realities with compassion.

Restricting creative freedom and the free flow of ideas strikes at the heart of the core values of an open society. By inhibiting artists’ ability to move freely in the performance, exhibition, or distribution of their work, United States President Trump’s January 27 Executive Order, blocking immigration from seven countries to the United States and refusing entry to all refugees, jettisons voices which contribute to the vibrancy, quality, and diversity of US cultural wealth and promote global understanding.

The Executive Order threatens the United States safe havens for artists who are at risk in their home countries, in many cases for daring to challenge repressive regimes. It will deprive those artists of crucial platforms for expression and thus deprive all of us of our best hopes for creating mutual understanding in a divided world. It will also damage global cultural economies, including the cultural economy of the United States.

Art has the power to transcend historical divisions and socio-cultural differences. It conveys essential, alternative perspectives on the world. The voices of cultural workers coming from every part of the world – writers, visual artists, musicians, filmmakers, and performers – are more vital than ever today, at a time when we must listen to others in the search for unity and global understanding, when we need, more than anything else, to imagine creative solutions to the crises of our time.

As cultural or human rights organisations, we urge the United States government to take into consideration all these serious concerns and to adopt any regulations of United States borders only after a process of deliberation, which takes into account the impact such regulations would have on the core values of the country, on its cultural leadership, as well as on the world as a whole.

African Arts Institute (South Africa)

Aide aux Musiques Innovatrices (AMI) (France)

Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts (USA)

Arterial (Africa)

Artistic Freedom Initiative (USA)

ArtsEverywhere (Canada)

Association of Art Museum Curators and Association of Art Museum Curators Foundation

Association Racines (Morocco)

Bamboo Curtain Studio (Taiwan)

Cartoonists Rights Network International

Cedilla & Co. (USA)

Culture Resource – Al Mawred Al Thaqafy (Lebanon)

International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art (CIMAM)

College Art Association (USA)

European Composer and Songwriter Alliance (ECSA)

European Council of Artists

Freemuse: Freedom of Expression for Musicians

Index on Censorship: Defending Free Expression Worldwide

Independent Curators International

International Arts Critics Association

International Network for Contemporary Performing Arts

The International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN)

Levy Delval Gallery (Belgium)

Geneva Ethnography Museum (Switzerland)

National Coalition Against Censorship (USA)

New School for Drama Arts Integrity Initiative (USA)

Observatoire de la Liberté de Création (France)

On the Move | Cultural Mobility Information Network

PEN America (USA)

Queens Museum (USA)

Roberto Cimetta Fund

San Francisco Art Institute (USA)

Stage Directors and Choreographers Society (SDC) (USA)

Tamizdat (USA)

Vera List Center for Art and Politics, New School (USA)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1486570424977-7a30af48-045a-3″ taxonomies=”3784″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Feb 2016 | Academic Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features, Poland

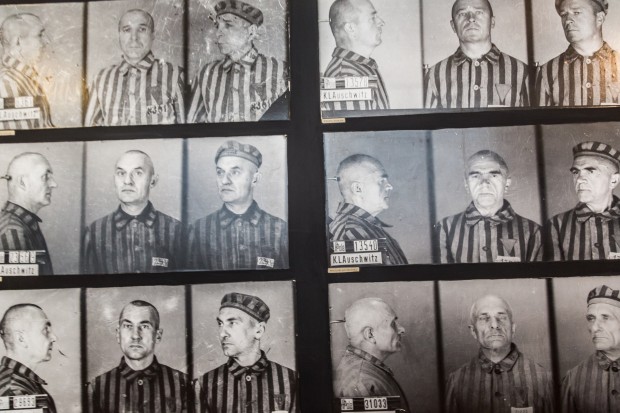

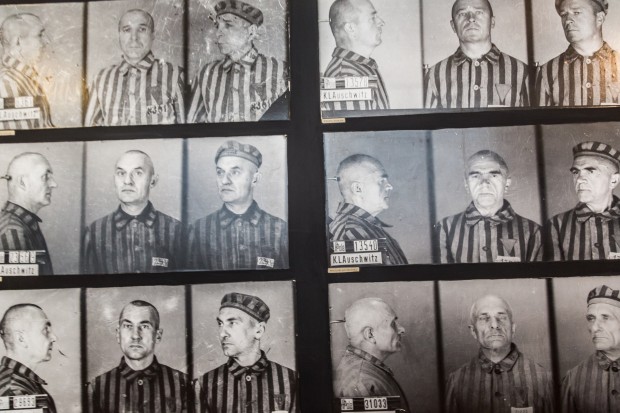

Still from an Auschwitz exhibition, 22 July 2014 in Oswiecim, Poland

When discussing academic freedom more than a century ago, German sociologist and philosopher Max Weber wrote: “The first task of a competent teacher is to teach his students to acknowledge inconvenient facts.” In Poland today, history appears to be an inconvenience for the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party, which is introducing legislation to punish the use of the term “Polish death camps”.

The Polish justice minister Zbigniew Ziobro announced earlier this month that the use of the phrase in reference to wartime Nazi concentration camps in Poland could now be punishable with up to five years in prison. If enacted, Poland would find itself in the unique position of being a country where both denying and discussing the Holocaust could land you in trouble with the law. Holocaust denial has been outlawed in Poland — under punishment of three years “deprivation of liberty” — since 1998.

Any suggestion of Polish complicity in Nazi war crimes against Jews brings with it, in the party’s own words, a “humiliation of the Polish nation”.

Of course, Poland was an occupied country which suffered terribly under Nazi Germany, so any talk of acquiescence understandably hits a nerve. As all good history students know, however, the discipline has its ambiguities and competing theories, from the acclaimed to the crackpot, and singular, simplistic narratives are rare. But few democratic countries in the world punish those who argue unpopular historical positions. Which is why legislating against uneasy truths is the same as legislating against academic freedom.

Two recent examples show the Polish government of doing just this. Firstly, Poland’s President Andrzej Duda made public his serious consideration to stripping the Polish-American Princeton professor of history at Princeton University Jan Gross of an Order of Merit — which he received in 1996 both for activities as a dissident in communist Poland in the 1960s and for his scholarship — over his academic work on Polish anti-Semitism. Gross outlined in his 2001 book Neighbors that the massacre of some 1,600 Jews from the Polish village of Jedwabne in July 1941 was committed by Poles, not Nazis. More recently, the historian has claimed that Poles killed more Jews than they did Germans during the war, which prompted the current action against him.

Some who disagree with his arguments have labelled Gross an “enemy” of Poland and a “traitor to the motherland”. The historian has hit back, saying in an interview with the Associated Press: “They want to take [the Order of Merit] away from me for saying what a right-wing, nationalist, xenophobic segment of the population refuses to recognise as facts of history.”

Academics too — Polish and otherwise — have come to his defence. Agata Bielik-Robson, professor of Jewish Studies at Nottingham University, points out that a “democracy has to have a voice of inner criticism”. She is worried that PiS is seeking to do away with such criticism in order “to produce a uniform historical perspective”.

Polish journalist and former activist in the anti-communist Polish trade union Solidarity Konstanty Gebert explained to Index on Censorship that PiS has made “convenient scapegoats” of people like Gross. “PiS is moving fast to reestablish a ‘positive narrative of Polish history’ by breaking with an alleged ‘pedagogy of shame’,” he said.

The party first tried — unsuccessfully — to outlaw the term “Polish death camps” in 2013 when it was in opposition. Should the law now pass, and you need help adhering to the proposed rules, the Auschwitz Museum has released an app to correct any “memory errors” you may experience. It detects thought crimes such as the words “Polish concentration camp” in 16 different languages on your computer, keeping you on the right track with prompts asking if you instead meant to write “German concentration camp”.

Poland may have lurched to the right with the election of PiS last October, but the party’s authoritarianism — from crackdowns on the media to moves to take control of the supreme court — seems positively Soviet in some respects. Attempts to control history, too hark back to the Polish People’s Republic of 1945-1989, when, in the words of Elizabeth Kridl Valkenier in the winter 1985 issue of Slavic Review, “cultural patterns” and “habits of mind” made it impossible to make historical interpretations “alien to that national sense of identity and a methodology at odds with the canons and objective scholarship”.

Gebert sees similarities between current and communist-era propaganda “in the basic formulation that there is nothing to be ashamed of in Polish history, and in Polish-Jewish relations in particular, and in the belief that there is one correct national viewpoint”.

However, now that freedom of speech exists, the government can and are being criticised for their actions. “This puts the government propaganda machine on the defensive,” Gebert said.

Just last week, President Duda spoke against the “defamation” of the Polish people “through the hypocrisy of history and the creation of facts that never took place”. He has made his motives clear: “Today, our great responsibility to create a framework […] with the dual aim of fostering a greater sense of patriotic pride at home while enhancing the country’s image abroad.”

It should be intolerable for the freedoms of any academic subject to be impinged for ideological ends. If academic freedom is to mean anything, it should include the right to tell uneasy truths, get things wrong and have you work challenged by the highest academic standards.

There’s only one place to turn for PiS to find an example of best practice on how to challenge Gross’ research, and that is to the very body the party will grant authority to on deciding on what is and isn’t a breach of the law regarding “Polish death camps”. Poland’s Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) produced several reports between 2000-03 challenging claims in Gross’ book on the Jedwabne massacre. It used research and reason — as opposed to censorship — to make the case that the historian didn’t get all the facts right. It found, for example, that German’s played a bigger part in the slaughter than Gross had claimed, and that the numbers killed were more likely to be around the 340 mark, rather than 1,600.

IPN should tread carefully, though. Any inconvenient truths with the potential to humiliate the Polish people could one day soon see it branded a “traitor”.

Ryan McChrystal is the assistant editor, online at Index on Censorship

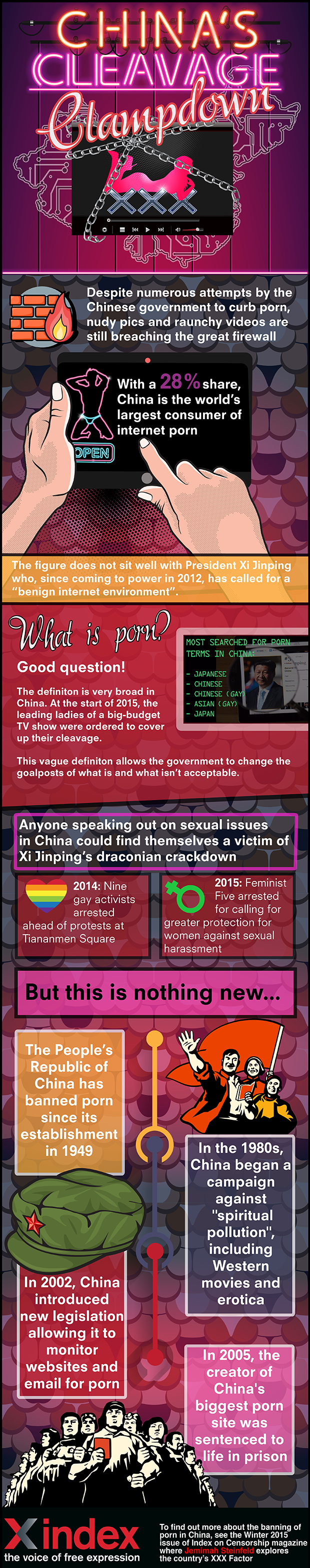

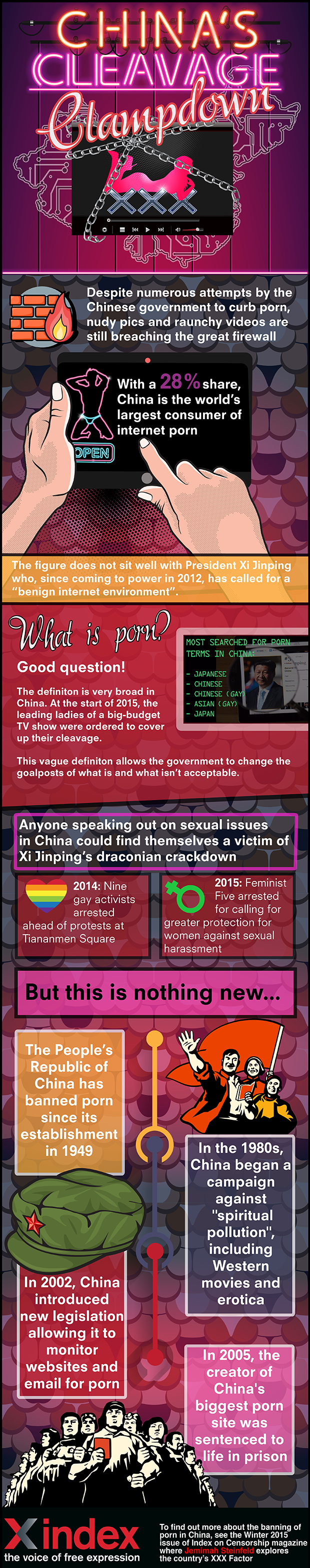

21 Dec 2015 | Asia and Pacific, China, Magazine, Volume 44.04 Winter 2015

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This is an extract from an article in the Winter 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. You can read the article in full here.

The streets of Dongguan in southern China have been quiet of late. In the past, China’s city of sin would hum to the sound of late-night karaoke bars offering more than just an innocent sing-along. Now these establishments have been forced underground or driven out of business entirely. Their chances of a future are not looking good. On 1 January 2016, new regulations will come into effect that dictate appropriate behaviour for the Communist Party’s 88 million members. As part of President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign, the new rules explicitly ban the trading of power for sex, money for sex, and adultery – but these are the foundations of business in Dongguan.

“In Dongguan, whose reputation, if not economy, practically rests on its skin trade, I’m told by several sources that the trade remains mostly out of sight nearly two years after a television report [led to]a sweeping crackdown,” said Robert Foyle Hunwick, a writer who has visited the city many times to research his forthcoming book The Pleasure Garden: China’s Hidden World of Sex, Drugs and the Super-Rich.

Dongguan is not the only city suffering from this campaign against smut – it has been lights out for many brothels across China. Nor is this crackdown limited to China’s Communist party members, as the January 2016 regulations imply. Instead, it forms part of a broader crackdown on China’s sex industry that has been underway since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012.

Enemy number one is internet pornography. In the most recent statistics, from 2014, China accounts for up to 28% of the world’s porn consumption, taking the global lead. It’s a statistic that does not sit well with Xi. Shortly into his term in power, he launched his first anti-pornography crusade, calling for a “benign internet environment”. An attempt was made to clear China’s internet of anything verging on pornography. A similar initiative was launched this summer, following the release of a video featuring a couple having sex in a Uniqlo store. It was the usual drill: sites were blocked or removed and anyone caught facilitating the production or distribution of pornography was arrested.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Feb 2014 | Digital Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Today Facebook celebrates its 10th anniversary. The social networking giant now has over 1.23 billion users, but there are still political leaders around the world who don’t want their country to have access to the site, or those who have banned it in the past amid fears it could be used to organise political rallies.

North Korea

Perhaps the most secretive country in the world little is known about internet access in Kim Jong-un’s nation. Although a new 3G network is available to foreign visitors, for the majority of the population the internet is off limits. But this doesn’t seem to bother many who, not knowing any different, enjoy the limited freedoms offered to them by the country’s intranet, Kwangmyong, which appears to be mostly used to post birthday messages.

A limited number of graduate students and professors at Pyongyang University of Science and Technology do have access to the internet (from a specialist lab) but in fear of the outside world many chose not to use it. Don’t expect to see Kim Jong-un’s personal Facebook page any time soon.

Iran

In Iran, however, political leaders have taken to social media- despite both Facebook and Twitter officially being extraordinarily difficult to access in the country. Even President Hassan Rouhani has his own Twitter account, although apparently he doesn’t write his own tweets, but access to these accounts can only be gained via a proxy server.

Facebook was initially banned in the country after the 2009 election amid fears that opposition movements were being organised via the website.

But things may be beginning to looking up as Iran’s Culture Minister, Ali Jannati, recently remarked that social networks should be made accessible to ordinary Iranians.

China

The Great Firewall of China, a censorship and surveillance project run by the Chinese government, is a force to be reckoned with. And behind this wall sits the likes of Facebook.

The social media site was first blocked following the July 2009 Ürümqi riots after it was perceived that Xinjiang activists were using Facebook to communicate, plot and plan. Since then, China’s ruling Communist Party has aggressively controlled the internet, regularly deleting posts and blocking access to websites it simply does not like the look of.

Technically, the ban on Facebook was lifted in September 2013. But only within a 17-square-mile free-trade zone in Shanghai and only to make foreign investors feel more at home. For the rest of China it is a waiting game to see if the ban lifts elsewhere.

Cuba

Facebook isn’t officially banned in Cuba but it sure is difficult to access it.

Only politicians, some journalists and medical students can legally access the web from their homes. For everyone else the only way to connect to the online world legally is via internet cafes. This may not seem much to ask but when rates for an hour of unlimited access to the web cost between $6 and $10 and the average salary is around $20 getting online becomes ridiculously expensive. High costs also don’t equal fast internet as web pages can take several minutes to load: definitely not value for money for the Caribbean country.

Bangladesh

The posting of a cartoon to Facebook saw the networking site shut down across Bangladesh in 2010. Satirical images of the prophet Muhammad, along with some of the country’s leaders, saw one man arrested and charged with “spreading malice and insulting the country’s leaders”. The ban lasted for an entire week while the images were removed.

Since then the Awami-League led government has directed a surveillance campaign at Facebook, and other social networking sites, looking for blasphemous posts.

Article continues below[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Stay up to date on freedom of expression” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that defends people’s freedom to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution. We fight censorship around the world.

To find out more about Index on Censorship and our work protecting free expression, join our mailing list to receive our weekly newsletter, monthly events email and periodic updates about our projects and campaigns. See a sample of what you can expect here.

Index on Censorship will not share, sell or transfer your personal information with third parties. You may may unsubscribe at any time. To learn more about how we process your personal information, read our privacy policy.

You will receive an email asking you to confirm your subscription to the weekly newsletter, monthly events roundup and periodic updates about our projects and campaigns.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Egypt

As Egyptians took to the streets in 2011 in an attempt to overthrow the regime of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak the government cut off access to a range of social media sites. As well as preventing protestors from using the likes of Facebook to foment unrest, many websites registered in Egypt could no longer be accessed by the outside world. Twitter, YouTube, Hotmail, Google, and a “proxy service” – which would have allowed Egyptians to get around the enforced restrictions- seemed to be blocked from inside the country.

The ban lasted for several days.

Syria

Syria, however, dealt with the Arab Spring in a different manner. Facebook had been blocked in the country since 2007 as part of a crackdown on political activism, as the government feared Israeli infiltration of Syrian social networking sites. In an unprecedented move in 2011 President Bashar al-Assad lifted the five year ban in an apparent attempt to prevent unrest on his own soil following the discontent in Egypt and Tunisia.

During the ban Syrians were still able to easily access Facebook and other social networking sites using proxy servers.

Mauritius

Producing fake online profiles of celebrities is something of a hobby to some people. However, when a Facebook page proclaiming to be that of Mauritius Prime Minister Navin Ramgoolam was discovered by the government in 2007 the entire Mauritius Facebook community was plunged into darkness. But the ban didn’t last for long as full access to the site was restored the following day.

These days it would seem Dr Ramgoolam has his own (real) Facebook account.

Pakistan

Another case of posting cartoons online, another case of a government banning Facebook. This time Pakistan blocked access to the website in 2010 after a Facebook page, created to promote a global online competition to submit drawings of the prophet Muhammad, was brought to their attention. Any depiction of the prophet is proscribed under certain interpretations of Islam.

The ban was lifted two weeks later but Pakistan vowed to continue blocking individual pages that seemed to contain blasphemous content.

Vietnam

During a week in November 2009, Vietnamese Facebook users reported an inability to access the website following weeks of intermittent access. Reports suggested technicians had been ordered by the government to block the social networking site, with a supposedly official decree leaked on the internet (although is authenticity was never confirmed). The government denied deliberately blocking Facebook although access to the site today is still hit-and-miss in the country.

Alongside this, what can be said on social networking sites like Facebook has also become limited. Decree 72, which came into place in September 2013, prohibits users from posting links to news stories or other news related websites on the social media site.

This article was published on 4 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1538131415482-d092e45b-9f66-5″ taxonomies=”136″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]