29 Sep 2021 | Afghanistan, Americas, Artistic Freedom Commentary and Reports, Asia and Pacific, Australia, Burma, Cuba, Ecuador, Europe and Central Asia, Israel, Lukashenko letters, Magazine, Magazine Contents, Middle East and North Africa, Religion and Culture, Russia, Syria, Turkey, Uganda, United Kingdom, United States, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021 Extras

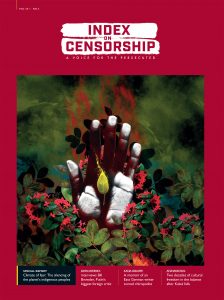

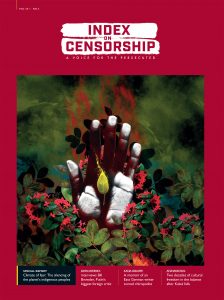

The Autumn issue of Index magazine focuses on the struggle for environmental justice by indigenous campaigners. Anticipating the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), in Glasgow, in November, we’ve chosen to give voice to people who are constantly ignored in these discussions.

Writer Emily Brown talks to Yvonne Weldon, the first aboriginal mayoral candidate for Sydney, who is determined to fight for a green economy. Kaya Genç investigates the conspiracy theories and threats concerning green campaigners in Turkey, while Issa Sikiti da Silva reveals the openly hostile conditions that environmental activists have been through in Uganda.

Going to South America, Beth Pitts interviews two indigenous activists in Ecuador on declining populations and which methods they’ve been adopting to save their culture against the global giants extracting their resources.

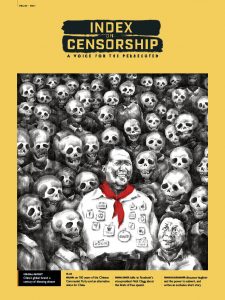

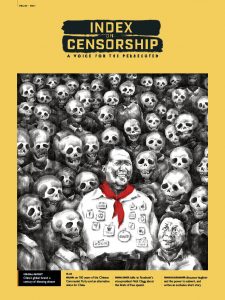

Cover of Index on Censorship Autumn 2021 (50-3)[/caption]

Cover of Index on Censorship Autumn 2021 (50-3)[/caption]

A climate of fear, by Martin Bright: Climate change is an era-defining issue. We must be able to speak out about it.

The Index: Free expression around the world today: the inspiring voices, the people who have been imprisoned and the trends, legislation and technology which are causing concern.

Pile-ons and censorship, by Maya Forstater: Maya Forstater was at the heart of an employment tribunal with significant ramifications. Read her response the Index’s last issue which discussed her case.

The West is frightened of confronting the bully, by John Sweeney: Meet Bill Browder. The political activist and financier most hated by Putin and the Kremlin.

An impossible choice, by Ruchi Kumar: The rapid advance of Taliban forces in Afghanistan has left little to no hope for journalists.

Words under fire, by Rachael Jolley: When oppressive regimes target free speech, libraries are usually top of their lists.

Letters from Lukashenka’s prisoners, by Maria Kalesnikava, Volha Takarchuk, Aliaksandr Vasilevich and Maxim Znak: Standing up to Europe’s last dictator lands you in jail. Read the heartbreaking testimony of the detained activists.

Bad blood, by Kelly Duda: How did an Arkansas blood scandal have reverberations around the world?

Welcome to hell, by Benjamin Lynch: Yangon’s Insein prison is where Myanmar’s dissidents are locked up. One photojournalist tells us of his time there.

Cartoon, by Ben Jennings: Are balanced debates really balanced? Ask Satan.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report” font_container=”tag:h2|font_size:22|text_align:left”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Credit: Xinhua/Alamy Live News

It’s not easy being green, by Kaya Genç: The Turkish government is fighting environmental protests with conspiracy theories.

It’s in our nature to fight, by Beth Pitts: The indigenous people of Ecuador are fighting for their future.

Respect for tradition, by Emily Brown: Australia has a history of “selective listening” when it comes to First Nations voices. But Aboriginal campaigners stand ready to share traditional knowledge.

The write way to fight, by Liz Jensen: Extinction Rebellion’s literary wing show that words remain our primary tool for protests.

Change in the pipeline? By Bridget Byrne: Indigenous American’s water is at risk. People are responding.

The rape of Uganda, by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Uganda’s natural resources continue to be plundered.Cigar smoke and mirrors, by James Bloodworth: Cuba’s propaganda must not blight our perception of it.

Denialism is not protected speech, by Oz Katerji: Should challenging facts be protected speech?

Permissible weapons, by Peter Hitchens: Peter Hitchens responds to Nerma Jelacic on her claims for disinformation in Syria.

No winners in Israel’s Ice Cream War, by Jo-Ann Mort: Is the boycott against Israel achieving anything?

Better out than in? By Mark Glanville: Can the ancient Euripides play The Bacchae explain hooliganism on the terraces?

Russia’s Greatest Export: Hostility to the free press, by Mikhail Khordokovsky: A billionaire exile tells us how Russia leads the way in the tactics employed to silence journalists.

Remembering Peter R de Vries, by Frederike Geeerdink: Read about the Dutch journalist gunned down for doing his job.

A right royal minefield, by John Lloyd: Whenever one of the Royal Family are interviewed, it seems to cause more problems.

A bulletin of frustration, by Ruth Smeeth: Climate change affects us all and we must fight for the voices being silenced by it. Credit: Gregory Maassen/Alamy[/caption]

Credit: Gregory Maassen/Alamy[/caption]

The man who blew up America, by David Grundy: Poet, playwright, activist and critic Amiri Baraka remains a controversial figure seven years after his death.

Suffering in silence, by Benjamin Lynch and Dr Parwana Fayyaz The award-winning poetry that reminds us of the values of free thought and how crucial it is for Afghan women.

Heart and Sole, by Mark Frary and Katja Oskamp: A fascinating extract gives us an insight into the bland lives of some of those who did not welcome the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Secret Agenda, by Martin Bright: Reforms to the UK’s Official Secret Act could create a chilling effect for journalists reporting on information in the public interest.

26 Jul 2021 | Africa, Bosnia, Burma, China, Europe and Central Asia, Hong Kong, Hungary, India, Magazine, Magazine Contents, Slapps, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021 Extras

Index’s new issue of the magazine looks at the importance of whistleblowers in upholding our democracies.

Featured are stories such as the case of Reality Winner, written by her sister Brittany. Despite being released from prison, the former intelligence analyst is still unable to speak out after she revealed documents that showed attempted Russian interference in US elections.

Playwright Tom Stoppard speaks to Sarah Sands about his life and new play title ‘Leopoldstatd’ and, 50 years on from the Pentagon Papers, the “original whistleblower” Daniel Ellsberg speaks to Index .

Features

Holding the rich and powerful to account by Martin Bright: We look at key whistleblower cases around the world and why they matter for free speech

The Index: Free expression round the world today: the inspiring voices, the people who have been imprisoned and the trends, legislation and technology which are causing concern

Why journalists need emergency safe havens by Rachael Jolley: Legal experts including Amal Clooney have called for a new type of visa to protect journalists

Spinning bomb by Nerma Jelacic: Disinformation and the assault on truth in Syria learned its lessons from the war in Bosnia

Identically bad by Helen Fortescue: Two generations of photojournalists document the political upheaval shaping Belarus 30 years apart

Always looking over our shoulders by Henry McDonald: Across the sectarian divide in Northern Ireland again, journalists are facing increasing threats

Crossing red lines by Fréderike Geerdink: The power struggle between the PUK and KDP is bad news for press freedom in Kurdistan

Cartoon by Ben Jennings: The reptaphile elite are taking over! So say the conspiracy theorists, anyway

People first but not the media by Issa Sikiti da Silva: There was hope for press freedom when Felix Tshisekedi took power in DR Congo, but that is now dwindling

Controlling the Covid message by Danish Raza and Somak Ghoshal: Covid-19 has crippled the Indian health service, but the government is more concerned with avoiding criticism

Special Report

Reality Winner. Credit: Michael Holahan/The Augusta ChronicleSpeaking for my silenced sister by Brittany Winner: Meet Reality Winner, the whistleblower still unable to speak out despite being released from prison

Feeding the machine by Mark Frary: Alexei Navalny has been on hunger strike in a penal colony outside Moscow, since his sentencing. Index publishes his writings from prison

An ancient virtue by Ian Foxley: A whistleblower explains the ancient Greek idea of parrhesia that is at the core of the whistleblower principle

Truthteller by Kaya Genç: Journalist Faruk Bildirici tells Index how one of Turkey’s most respected newspapers became an ally of Islamists

The price of revealing oil’s dirty secrets: Whistleblower Jonathan Taylor has been hounded since revealing serious cases of bribery within the oil industry

The original whistleblower: 50 years on from the Pentagon Papers, whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg speaks to Index

Fishrot, the global stench of scandal: Former Samherji employee Johannes Stefansson exposed corruption and the plundering of Namibian fish stocks

Comment

What is a woman? by Kathleen Stock and This is hate, not debate by Phoenix Andrews: Two experts debate the case of Maya Forstater, in which Index legally intervened, and if the matter is a case of hate speech

Battle cries by Abbad Yahya: The lost voice of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

A nightmare you can’t wake up from by Nandar: A feminist activist forced to flee her home country after the military coup in February

Trolled by the president by Michela Wrong: Rwanda’s leader Paul Kagame is known for attacking journalists. What is it like to incur his wrath?

When the boot is on the other foot by Ruth Smeeth: People must fight not only for their own rights, but for the free speech of the people they do not agree with

Culture

Playwright Tom Stoppard. Credit: Liba Taylor/Alamy Stock Photo

Uncancelled by Sarah Sands: An interview with the playwright Sir Tom Stoppard on his new play, Leopoldstadt, and the inspiration behind it

No light at the end of the tunnel by Benjamin Lynch: Yemeni writer Bushra al-Maqtari provides us with an exclusive extract of her award-winning novel, Behind the Sun

Dead poets’ society by Mark Frary: The military in Myanmar is targeting dissenting voices. Poets were among the first to be killed

Politics or passion? by Mark Glanville: Contemporary poet Stanley Moss on his long-standing love for China

Are we becoming Hungary-lite? by Jolyon Rubinstein: Comedian Jolyon Rubinstein on the death of satire

28 Apr 2021 | Africa, Burma, China, Hong Kong, Magazine, Magazine Contents, Slapps, United States, Volume 50.01 Spring 2021, Volume 50.01 Spring 2021 extras

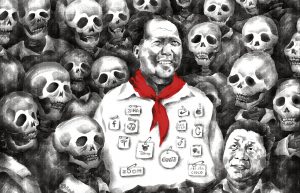

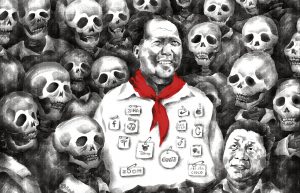

Illustration: Badiucao

Index looks back on 100 years of the Chinese Communist Party and how their censorship laws continue to shape the lives of people around the world and threaten their right to free speech. Inside this edition are articles by exiled writer Ma Jian and an interview with Facebook’s vice-president for global affairs, former UK deputy Prime minister Nick Clegg; as well as an exclusive short story from acclaimed writer Shalom Auslander.

Acting editor Martin Bright said: “I am delighted to introduce the latest edition of Index which marks the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party.”

“This year also marks the 50th anniversary of the magazine and I am proud that we are continuing the founders’ legacy of opposition to totalitarianism.”

“In this Spring edition of Index we are particularly pleased to publish an exclusive essay by the celebrated Chinese writer Ma Jian, who suggests that an alternative tradition of tolerance and freedom is still possible.”

A century of silencing dissent by Martin Bright: We look at 100 years of the Chinese Communist Party and the methods of control that it has adapted to stifle free expression and spread its ideas throughout the world

A century of silencing dissent by Martin Bright: We look at 100 years of the Chinese Communist Party and the methods of control that it has adapted to stifle free expression and spread its ideas throughout the world

The Index: Free expression round the world today: the inspiring voices, the people who have been imprisoned and the trends, legislation and technology which are causing concern

Fighting back against the menace of Slapps by Jessica Ní Mhainín: Governments continue to threaten journalists with vexatious law suits to stop critical reporting

Friendless Facebook by Sarah Sands: An interview with Facebook vice-president Nick Clegg about being a British liberal at the heart of the US tech giant

Standing up to a global giant by Steven Donziger: A lawyer who has gone head to head with the oil industry since 1993 at great personal cost tells his story

Fear and loathing in Belarus by Yahuen Merkis and Larysa Shchryakova: The crackdown on journalism has continued with arrests. Read the testimony of two reporters

Killed by the truth by Bilal Ahmad Pandow: Babar Qadri was one of Kashmir’s most strident voices, until he was gunned down in his garden

Cartoon by Ben Jennings: Arguments about the removal of statues cause a stir

The martial art of free speech by Ari Deller and Laura Janner-Klausner: The question of Cancel Culture continues to rage. Is it really a problem?

Ma Jian

Burning through censorship: Censorship-busting online organisation GreatFire celebrates its 10th anniversary

The party is your idol by Tianyu M. Fang: China’s propaganda is adapting to target young people

Past imperfect by Rachael Jolley: Four historians explain how the CCP shaped China and ask if globalisation will be its undoing

Turkey changes its tune by Kaya Genç: Uighur refugees living in Turkey find themselves victims of a change in foreign policy

The human face and the boot by Ma Jian: The acclaimed writer-in-exile reflects on 100 years of the CCP and its legacy of bloodshed

A moral hazard by Sally Gimson: Universities around the world and the CCP’s challenges to academic freedom

Director’s cuts by Chris Yeung: Hong Kong broadcaster RTHK has been squeezed by China’s tightening control

Beijing buys Africa’s silence by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Africa’s rich natural resources are being hoovered up by China

A new world order by Natasha Joseph: Journalist Azad Essa found when he wrote about China in Africa, his writing was silenced

A most unlikely ally by Stefan Pozzebon: Paraguay has long been an ally of Taiwan, but it’s paying an economic price

China’s artful dissident: A profile of our cover artist: the exiled cartoonist Badiucao.

Lies, damned lies and fake news by Nick Anstead: Fake news is rife, rampant and harmful. And we can only counter it by making sure that the truth is heard

Censorship? Hardly by Clive Priddle: Even the most controversial book usually finds a publisher after it has been turned down

A voice for the persecuted by Ruth Smeeth: As Index celebrates its 50 year anniversary, we note why free speech is still important

Collective ©ALEXANDER NANAU PRODUCTION

Don’t joke about Jesus by Shalom Auslander: An exclusive short story based on a joke by the acclaimed author of Mother for Dinner

Poet who haunts Ukraine by Steve Komarnyckyj: Vasyl Stus, the writer who remains a Ukrainian hero, 35 years after perishing in a Soviet gulag

The freedom of exile by Khaled Alesmael, Leah Cross: A young refugee Syrian writer on the love between Arab men

Forbidden love songs by Benjamin Lynch: Iran’s underground pop music scene upsets the regime

Reviews: Saudi Arabia’s murder of Jamal Khashoggi, USA Gymnastics and healthcare in Romania: we review three new documentaries

War of the airwaves by Ian Burrell: The Chinese government faces difficulties with its propaganda network CGTN

16 Sep 2019 | News and features, Volume 48.03 Autumn 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Arthur Miller, American playwright (Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikipedia)

It is always necessary to ask how old a writer is who is reporting his impressions of a social phenomenon. Like the varying depth of a lens, the mind bends the light passing through it quite differently according to its age. When I first experienced Prague in the late 60s, the Russians had only just entered with their armies; writers (almost all of them self-proclaimed Marxists if not Party members) were still unsure of their fate under the new occupation, and when some 30 or 40 of them gathered in the office of Listy to ‘interview’ me, I could smell the apprehension among them. And indeed, many would soon be fleeing abroad, some would be jailed, and others would never again be permitted to publish in their native language. Incredibly, that was almost a decade ago.

But since the first major blow to the equanimity of my mind was the victory of Nazism, first in Germany and later in the rest of Europe, the images I have of repression are inevitably cast in fascist forms. In those times the communist was always the tortured victim, and the Red Army stood as the hope of man, the deliverer. So to put it quite simply, although correctly, I think, the occupation of Czechoslovakia was the physical proof that Marxism was but one more self-delusionery attempt to avoid facing the real nature of power, the primitive corruption by power of those who possess it. In a word, Marxism has turned out to be a form of sentimentalism toward human nature, and this has its funny side. After all, it was initially a probe into the most painful wounds of the capitalist presumptions, it was scientific and analytical.

What the Russians have done in Czechoslovakia is, in effect, to prove in a western cultural environment that what they have called socialism simply cannot tolerate even the most nominal independent scrutiny, let alone an opposition. The critical intelligence itself is not to be borne, and in the birthplace of Kafka and of the absurd in its subtlest expression absurdity emanates from the Russian occupation like some sort of gas which makes one both laugh and cry. Shortly after returning home from my first visit to Prague mentioned above, I happened to meet a Soviet political scientist at a high-level conference where he was a participant representing his country and I was invited to speak at one session to present my views of the impediments to better cultural relations between the two nations. Still depressed by my Czech experience, I naturally brought up the invasion of the country as a likely cause for American distrust of the Soviets, as well as the United States aggression in Vietnam from the same detente viewpoint.

That had been in the morning; in the evening at a party for all the conference participants, half of them Americans, I found myself facing this above-mentioned Soviet whose anger was unconcealed. ‘It is amazing,’ he said, ‘that you – especially you as a Jew – should attack our action in Czechoslovakia.’ Normally quite alert to almost any reverberations of the Jewish presence in the political life of our time, I found myself in a state of unaccustomed and total confusion at this remark, and I asked the man to explain the connection. ‘But obviously,’ he said (and his face had gone quite red and he was quite furious now) ‘we have gone in there to protect them from the West German fascists.’

I admit that I was struck dumb. Imagine! The marching of all the Warsaw Pact armies in order to protect the few Jews left in Czechoslovakia! It is rare that one really comes face to face with such fantasy so profoundly believed by a person of intelligence. In the face of this kind of expression all culture seems to crack and collapse; there is no longer a frame of reference.

In fact, the closest thing to it that I could recall were my not infrequent arguments with intelligent supporters or apologists for our Vietnamese invasion. But at this point the analogy ends, for it was always possible during the Vietnam war for Americans opposed to it to make their views heard, and, indeed, it was the widespread opposition to the war which finally made it impossible for President Johnson to continue in office. It certainly was not a simple matter to oppose the war in any significant way, and the civilian casualties of protest were by no means few, and some – like the students at the Kent State College protest – paid with their lives. But what one might call the unofficial underground reality, the version of morals and national interest held by those not in power, was ultimately expressed and able to prevail sufficiently to alter high policy. Even so, it was the longest war ever fought by Americans.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

The sin of power is to not only distort reality but to convince people that the false is true, and that what is happening is only an invention of enemies

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Any discussion of the American rationales regarding Vietnam must finally confront something which is uncongenial to both Marxist and anti-Marxist viewpoints, and it is the inevitable pressure, by those holding political power, to distort and falsify the structures of reality. The Marxist, by philosophical conviction, and the bourgeois American politician, by practical witness, both believe at bottom that reality is quite simply the arena into which determined men can enter and reshape just about every kind of relationship in it. The conception of an objective reality which is the summing up of all historical circumstances, as well as the idea of human beings as containers or vessels by which that historical experience defends itself and expresses itself through common sense and unconscious drives, are notions which at best are merely temporary nuisances, incidental obstructions to the wished for remodelling of human nature and the improvements of society which power exists in order to set in place.

The sin of power is to not only distort reality but to convince people that the false is true, and that what is happening is only an invention of enemies. Obviously, the Soviets and their friends in Czechoslovakia are by no means the only ones guilty of this sin, but in other places, especially in the West, it is possible yet for witnesses to reality to come forth and testify to the truth. In Czechoslovakia the whole field is pre-empted by the power itself.

Thus a great many people outside, and among them a great many artists, have felt a deep connection with Czechoslovakia – but precisely because there has been a fear in the West over many generations that the simple right to reply to power is a tenuous thing and is always on the verge of being snipped like a nerve. I have, myself, sat at dinner with a Czech writer and his family in his own home and looked out and seen police sitting in their cars down below, in effect warning my friend that our ‘meeting’ was being observed. I have seen reports in Czech newspapers that a certain writer had emigrated to the West and was no longer willing to live in his own country, when the very same man was sitting across a living-room coffee table from me. And I have also been lied about in America by both private and public liars, by the press and the government, but a road – sometimes merely a narrow path – always remained open before my mind, the belief that I might sensibly attempt to influence people to see what was real and so at least to resist the victory of untruth.

I know what it is to be denied the right to travel outside my country, having been denied my passport for some five years by our Department of State. And I know a little about the inviting temptation to simply get out at any cost, to quit my country in disgust and disillusion, as no small number of people did in the McCarthy 50s and as a long line of Czechs and Slovaks have in these recent years. I also know the empty feeling in the belly at the prospect of trying to learn another nation’s secret language, its gestures and body communications without which a writer is only half-seeing and half-hearing. More important, I know the conflict between recognising the indifference of the people and finally conceding that the salt has indeed lost its savour and that the only sensible attitude toward any people is cynicism.

So that those who have chosen to remain as writers on their native soil despite remorseless pressure to emigrate are, perhaps no less than their oppressors, rather strange and anachronistic figures in this time. After all, it is by no means a heroic epoch now; we in the West as well as in the East understand perfectly well that the political and military spheres – where ‘heroics’ were called for in the past – are now merely expressions of the unmerciful industrial-technological base. As for the very notion of patriotism, it falters before the perfectly obvious interdependence of the nations, as well as the universal prospect of mass obliteration by the atom bomb, the instrument which has doomed us, so to speak, to this lengthy peace between the great powers.

That a group of intellectuals should persist in creating a national literature on their own ground is out of tune with our adaptational proficiency which has flowed from these developments. It is hard anymore to remember whether one is living in Rome or New York, London or Strasbourg, so homogenised has western life become. The persistence of these people may be an inspiration to some but a nuisance to others, and not only inside the oppressing apparatus but in the West as well. For these so-called dissidents are apparently upholding values at a time when the first order of business would seem to be the accretion of capital for technological investment.

It need hardly be said that by no means everybody in the West is in favour of human rights, and western support for eastern dissidents has more hypocritical self-satisfaction in it than one wants to think too much about. Nevertheless, if one has learned anything at all in the past 40 or so years, it is that to struggle for these rights (and without them the accretion of capital is simply the construction of a more modern prison) one has to struggle for them wherever the need arises.

That this struggle also has to take place in socialist systems suggests to me that the fundamental procedure which is creating violations of these rights transcends social systems – a thought anathematic to Marxists but possibly true nevertheless. What may be in place now is precisely a need to erect a new capital structure, be it in Latin America or the Far East or underdeveloped parts of Europe, and just as in the 19th century in America and England it is a process which always breeds injustice and the flaunting of human spiritual demands because it essentially is the sweating of increasing amounts of production and wealth from a labour force surrounded, in effect, by police. The complaining or reforming voice in that era was not exactly encouraged in the United States or England; by corrupting the press and buying whole legislatures, capitalists effectively controlled their opposition, and the struggle of the trade union movement was often waged against firing rifles.

There is of course a difference now, many differences. At least they are supposed to be differences, particularly that the armed force is in the hands of a state calling itself socialist and progressive and scientific, no less pridefully than the 19th-century capitalisms boasted by their Christian ideology and their devotion to the human dimension of political life as announced by the American Bill of Rights and the French Revolution. But the real difference now is the incomparably deeper and more widespread conviction that man’s fate is not ‘realistically’ that of the regimented slave. It may be that despite everything, and totally unannounced and unheralded, a healthy scepticism toward the powerful has at last become second nature to the great mass of people almost everywhere. It may be that history, now, is on the side of those who hopelessly hope and cling to their native ground to claim it for their language and ideals.

The oddest request I ever heard in Czechoslovakia – or anywhere else – was to do what I could to help writers publish their works – but not in French, German or English, the normal desire of sequestered writers cut off from the outside. No, these Czech writers were desperate to see their works in Czech! Somehow this speaks of something far more profound than ‘dissidence’ or any political quantification. There is something like love in it, and in this sense it is a prophetic yearning and demand.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Border forces: How barriers to free thought got tough” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F06%2Fmagazine-judged-how-governments-use-power-to-undermine-justice-and-freedom%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2019 Index on Censorship magazine looks how governments are using borders to restrict free speech and the flow of ideas[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”108826″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/06/magazine-judged-how-governments-use-power-to-undermine-justice-and-freedom/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Cover of Index on Censorship Autumn 2021 (50-3)[/caption]

Cover of Index on Censorship Autumn 2021 (50-3)[/caption]

Credit: Gregory Maassen/Alamy[/caption]

Credit: Gregory Maassen/Alamy[/caption]