7 Oct 2015 | Middle East and North Africa, mobile, Morocco, News and features

Index on Censorship Arts award winner 2015: Mouad ‘El Haqed’ Belghouat

Generally speaking, Arabic hip hop comes in two categories. There are rappers in the Gulf who like to brag about how great it is to be really, really rich. Then there are artists in places like Palestine and Algeria who use their work to talk about the endemic problems they face in their communities: disenfranchisement, discrimination, destitution and violence.

Index on Censorship Arts award winner Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat falls under the latter category. Hailing from Morocco, where the youth have been keen consumers of hip hop for many years, El Haqed has had a lot of attention since the Arab Spring. Rapping about poverty, police corruption and oppression in the country, the 24-year old has been felt the full force of the law. Arrested for the first time in 2011, he spent two years in prison before being arrested twice more because of his music.

Index spoke with El Haqed in June when he had just returned to Morocco in high spirits following a tour of Norway, Sweden and Denmark, and was looking forward to performing for the first time in his hometown of Casablanca. Unfortunately, the Moroccan state went to extraordinary lengths — blocking off roads and ordering an electricity company to shut off power — to ensure the concert didn’t go ahead. He is effectively banned from performing live or appearing on TV or radio.

Asked why the Moroccan government wants to silence him so badly, El Haqed said: “Because I continue to speak out against them and fight for freedom of expression.” On several occasions, the authorities have asked El Haqed to renounce his views. “They want me to say that we live in a democracy and that everything is OK, but I have always refused.”

An all too frequent but often unavoidable fact of life as an artist under siege is that there will be times when keeping a low profile seems necessary. While El Haqed is still writing and recording music, he isn’t currently posting to YouTube as he was before. “Publishing music at the minute would only cause more problems,” he explains. He adds, however, that this is only a temporary setback, and publishing on YouTube and to his tens of thousands of social media followers is very much a part of his future plans.

One area of extreme difficulty has been finding the right people — including a producer — to work with. El Haqed used to write music with other artists in Morocco, but this has become an inconvenience. “Musicians were told by the authorities to stop working with me, or they would be made to,” he says.

One area of extreme difficulty has been finding the right people — including a producer — to work with. El Haqed used to write music with other artists in Morocco, but this has become an inconvenience. “Musicians were told by the authorities to stop working with me, or they would be made to,” he says.

Although in the past El Haqed pushed the authorities to give him permission to perform in Morocco, he is resigned to the fact this may never happen. But there is hope. Visa applications pending, he has been invited to spend a week in Florence, Italy, in October for an exchange with Italian musicians, a debate on the music of the new generation and to perform in concert. A major focus of this visit will be to facilitate artistic collaboration.

He has also been invited to perform in Belgium in October by at the 25th anniversary of the Moroccan Association of Human Rights due to his being a “committed musician and human rights defender”.

Like one in five people his age in Morocco, El Haqed doesn’t currently have a job and relies heavily on family and friends for support. While it may be easier if he left Morocco to pursue a career in music, he has no intention of relocating.

“I love my country, and while I want to perform abroad, I will always come back to Morocco,” he says.

Index on Censorship demands Moroccan authorities end their harassment of El Haqed and allow him, and others like him, to perform in the country.

Nominations for the 2016 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards are currently open. Act now.

7 Oct 2015 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns, mobile

Today marks the 200th day of Bahraini prisoner of conscience Dr Abduljalil al-Singace’s protest. Since 21 March, Dr al-Singace has boycotted all solid food in protest of the treatment of inmates at the Central Jau Prison.

We, the undersigned NGOs, call for Dr al-Singace’s immediate and unconditional release, and the release of all political prisoners detained in Bahrain. We voice our solidarity with Dr al-Singace’s continued protest and call on the United Kingdom and all European Union member states, the United States and the United Nations to raise his case, and the cases of all prisoners of conscience, with Bahrain, both publicly and privately.

Dr al-Singace is a former Professor of Engineering at the University of Bahrain, an academic and a blogger. He is a 2007 Draper Hills Fellow at Stanford University’s Center on Democracy Development, and the Rule of Law. He has long campaigned for an end to torture and political reform, writing on these and other subjects on his blog, Al-Faseela. Bahraini Internet Service Providers continue to ban access to the blog and Dr al-Singace has suffered arbitrary detention and torture on multiple occasions. In June 2011, a military court sentenced Dr al-Singace to life imprisonment alongside other prominent protest leaders, collectively known as the ‘Bahrain 13’. He is considered a prisoner of conscience.

Dr al-Singace’s current protest began in response to the violent response of the Ministry of Interior to a riot that took place in the Central Jau Prison on 10 March 2015. Though only a minority of inmates participated in the riot, police collectively punished all detainees, subjecting them to beatings and other humiliating and degrading acts; depriving them of sleep and food; and denying them access to sanitation facilities. Dr al-Singace objects to the humiliating treatment and arbitrary detention to which prison authorities subject him and other prisoners of conscience. Additionally, Dr al-Singace rejects being labelled a criminal, as the government convicted him in 2011 on grounds relating to his peaceful exercise of his freedoms of speech and assembly.

Since Dr al-Singace began his protest, the international community has expressed concerns over the treatment of inmates at Bahrain’s largest prison complex and the condition of Dr al-Singace in particular. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights raised the issue of torture in Bahrain’s prisons in June. In July, the European Parliament passed a resolution on Bahrain calling for the unconditional release of prisoners of conscience, naming Dr al-Singace. The United States clarified its concerns regarding Dr al-Singace in August. The United Kingdom has also expressed its concerns over Bahrain.

In June 2015, NGOs launched a social media campaign for Dr al-Singace – #singacehungerstrike – alongside the University College Union. Since then, NGOs also organised protests outside the Bahrain Embassy, London, and the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office. On 27 August, the 160th day of Dr al-Singace’s protest, 41 NGOs issued an urgent appeal for the release of Dr al-Singace.

For over six months, Dr al-Singace has subsisted on water, fluids and IV injections for sustenance. He is currently interred at the prison clinic. Prison authorities seem to have finally begun to take notice of the international attention his case is attracting, as Dr al-Singace recently received treatment for a nose injury he suffered during his torture in 2011. He had waited over four years to receive such treatment. He also suffered damage to his ear as a result of torture, but has not received adequate medical attention for this injury.

According to Dr al-Singace’s family, the prison authorities will only transfer him to a civilian hospital for treatment if he agrees to wear a prisoner’s uniform, which he refuses to do on the grounds that he is a prisoner of conscience and not a criminal. Since the beginning of his protest, Dr al-Singace has lost 20 kilograms in weight. He is often dizzy and his hair is falling out. He survives on nutritional drinks, oral rehydration salts, glucose, water and an IV drip, and his family states that he is “on the verge of collapse.”

In the prison clinic, Dr al-Singace is not allowed to leave the building and is effectively held in solitary confinement. Though the clinic staff tends to him, he is not allowed to interact with other prison inmates and his visitation times are irregular. Authorities have now lifted an unofficial ban on Dr al-Singace receiving writing and reading materials, but access is still limited: prison staff have now given him a pen, but have still not allowed him access to any paper. The government has also denied Dr al-Singace permission to receive magazines sent to him in an English PEN-led campaign, despite promising to allow him to do so. He has no ready access to television, radio or print media.

We demand Dr Abduljalil al-Singace’s immediate release, and urge the international community to raise his case with Bahrain.

Signatories:

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

ARTICLE 19

Bahrain Centre for Human Rights (BCHR)

Bahrain Institute of Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

English Pen

European – Bahraini Organisation for Human Rights (EBOHR)

Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR)

Index on Censorship

International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

Lawyer’s Rights Watch Canada (LRWC)

No Peace Without Justice (NPWJ)

PEN Canada

PEN International

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

Scholars at Risk Network (SAR)

Sentinel Human Rights Defenders

The Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI)

The European Centre for Democracy and Human Rights (ECDHR)

The Nonviolent Radical Party Transnational and Transparty (NRPTT)

For more and background information, read the previous statement here.

7 Oct 2015 | Campaigns, mobile, Statements, Syria

Syria’s authorities should immediately reveal the whereabouts of Bassel Khartabil, a software developer and defender of freedom of expression, 31 organizations said today. Syrian authorities transferred Khartabil, who has been detained since 2012, from Adra central prison to an undisclosed location on October 3, 2015.

Khartabil managed to inform his family on October 3 that security officers had ordered him to pack but did not reveal his destination. His family has not received any official information but believe based on unconfirmed information they received that he may have been transferred to the military-run field court inside the Military Police base in Qaboun.

“There are real fears that Khartabil has been transferred back to the torture-rife facilities run by Syria’s security forces,” a spokesperson for the groups said. “Khartabil should be on his way out of jail rather than being disappeared again.”

The organizations repeated their call for the immediate release of Khartabil who is facing field court proceedings for his peaceful activities in support of freedom of information.

International law defines a disappearance action by state authorities to deprive a person of their liberty and then refuse to provide information regarding the person’s fate or whereabouts.

Military Intelligence detained Khartabil on March 15, 2012 and he has remained in detention since. He was initially held incommunicado in the Military Intelligence Detention facility in Kafr Souseh for eight months and later in the military jail in Sednaya, where prison personnel tortured him for three weeks, he later told his family. Officials provided Khartabil’s family with no information about where or why he was in custody until December 24, 2012, when authorities moved him to Adra central prison, where Khartabil was eventually allowed visits from his family.

A Syrian of Palestinian parents, Khartabil is a 34-year old computer engineer who worked to build a career in software and web development. Before his arrest, he used his technical expertise to help advance freedom of speech and access to information via the Internet. Among other projects, he founded Creative Commons Syria, a nonprofit organization that enables people to share artistic and other work using free legal tools.

Khartabil has received a number of awards including the 2013 Index on Censorship Digital Freedom Award for using technology to promote an open and free Internet. Foreign Policy magazine named Khartabil one of its Top 100 Global Thinkers of 2012, “for insisting, against all odds, on a peaceful Syrian revolution.”

Military Field courts in Syria are exceptional courts that have secret closed-door proceedings and do not allow for the right to defense. According to accounts of released detainees who appeared before them, the proceedings of these courts were perfunctory, lasting minutes, and in absolute disregard of international standards of minimum fairness. During a field court proceeding on December 9, 2012, a military judge interrogated Khartabil, for a few minutes but he had heard nothing about his legal case since then.

“Bassel has always been a leading advocate for more transparency in Syria and the authorities should immediately reveal his whereabouts and reunite him with his family,” the spokesperson for the groups said.

List of signatories:

- Action des Chrétiens pour l’Abolition de la Torture (ACAT)

- Amnesty International

- Arab Foundation for Development and Citizenship

- Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI)

- Association for Progressive Communications

- Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS)

- Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF)

- Euromed Rights (EMHRN)

- FIDH (International Federation for Human Rights), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

- Front Line Defenders

- Global Voices Advox

- Gulf Center for Human Rights (GCHR)

- Humanist Institute for Cooperation with Developing Countries (HIVOS)

- Human Rights Watch (HRW)

- Index on Censorship

- Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR)

- International Service for Human Rights (ISHR)

- Lawyers Rights Watch Canada (LRWC)

- No Peace Without Justice (NPWJ)

- One world foundation for development

- Pax for Peace – Netherland

- Pen International

- RAW in WAR (Reach All Women in WAR)

- Reporters without Borders (RSF)

- Sisters Arab Forum for Human Rights (SAF)

- SKeyes Center for Media and Cultural Freedom

- Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR)

- The Day After

- Violations Documentation Center in Syria (VDC)

- Vivarta

- World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

6 Oct 2015 | Belarus, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

In Belarus, dozens of freelance journalists were fined between 2014 and 2015 for working for foreign media without an accreditation from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In a country dominated by state-run media, foreign outlets offer an alternative source of information.

Under Belarusian law, freelance journalists who co-operate with foreign media outlets are not considered legal employees of the organisation in question and aren’t entitled to receive the required accreditation. The first freelancer penalised was videographer Ales Dzianisau from Hrodna, a city in western Belarus. He was accused of illegally producing a video which ran on Belsat TV — a Polish state-run channel aimed at providing an alternative to the censorship of Belarusian television — about the opening night of a rendition of Goethe’s play Faust. He was fined €300.

Under Article 22.9(2) of the Belarusian Code on Administrative Offence, the courts can judge journalistic activities without an accreditation as illegal. In each case, the reason for the journalist having committed an offence was not the content of their work, but that they were published through foreign media.

As a rule, the police must consult witnesses — usually a person who was interviewed by the journalist — to prove that a work was made by the journalist accused. This doesn’t always appear to be the case.

An article published by Aliaksandr Burakou on the German website Deutsche Welle resulted in court hearings, talks at the tax office and the seizure of flash drives and computer systems. On 16 September 2014, Burakou’s apartment was searched, as was that of his parents. The journalist was charged with work without accreditation and fined €450. Burakou’s appeal to the country’s Supreme Court was rejected in May 2015.

The Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) strongly condemns the continued prosecution of freelancers. It called the prosecutions a gross violation of the standards of freedom of expression.

In December 2014, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatović wrote in a letter to the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Belarus, Vladimir Makei, stating: “These undue restrictions stifle free expression and free media. Mandatory accreditation requirements for journalists should be reformed as they hinder journalists from doing their job.” She reiterated her call on to stop imposing restrictive measures on freelance journalists in April 2015.

The European Federation of Journalists (EFJ) issued a statement on the situation at its June 2015 annual meeting. It called on the Belarusian authorities to drop the practice of holding freelancers accountable for work without the accreditation. The union also called on the OSCE and the Council of Europe to pay more attention to violations of freelancers’ rights in Belarus.

Nevertheless, since the beginning of 2015, 28 Belarusian journalists have been fined with 23 of those cases taking place in the last six months. Since April 2014, 38 freelance journalists have been fined €200-500, totalling over €8,000.

Dzianisau, the freelance cameraman penalised for making video reports in Hrodna, said: “The most complicated thing for me in this situation is that the authorities shut off the air. At present, I cannot report in the history museum or the museum of religions. I cannot report in the puppet theater, and now in the exhibition hall on Azheshka Street.”

Some freelancers have been brought to trial several times during this period. Kastus Zhukouski has been fined six times and Alina Litvinchuk four times. Some see the pressure on the media in Belarus as increasing due to the upcoming presidential elections on 11 October 2015.

Not so long ago, President Alexander Lukashenko was asked what should be done about journalists receiving fines. In response, he acknowledged that the practice was improper and the matter should be investigated by his press service.

However, many Belarusian freelancers do not believe their situation will change soon. Larysa Shchyrakova, a freelance journalist from Gomel who has been penalised twice this year for co-operating with foreign media, said: “I do not believe there will be any liberalisation because it is contrary to the logic of the authorities. The system in Belarus is ineffective and the prosecution of journalists will always be a priority for the government.”

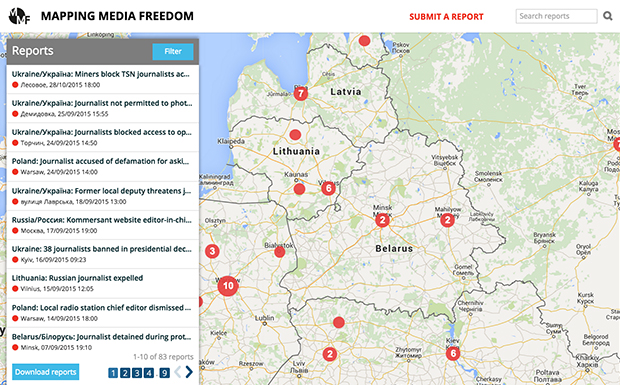

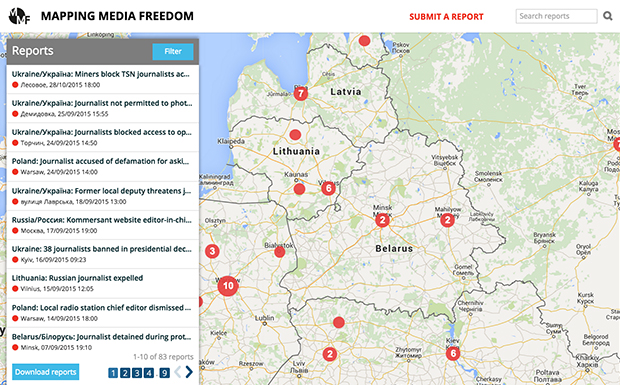

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

One area of extreme difficulty has been finding the right people — including a producer — to work with. El Haqed used to write music with other artists in Morocco, but this has become an inconvenience. “Musicians were told by the authorities to stop working with me, or they would be made to,” he says.

One area of extreme difficulty has been finding the right people — including a producer — to work with. El Haqed used to write music with other artists in Morocco, but this has become an inconvenience. “Musicians were told by the authorities to stop working with me, or they would be made to,” he says.