5 Feb 2019 | Artistic Freedom, Artistic Freedom Statements, Campaigns -- Featured, Press Releases, Statements, Uganda

More than 130 musicians, writers and artists, together with many British and Ugandan members of parliament, have signed a petition calling on Uganda to drop plans for regulations that include vetting songs, videos and film scripts prior to their release. Musicians, producers, promoters, filmmakers and all other artists would also have to register with the government and obtain a licence that can be revoked for a range of violations.

Index on Censorship is deeply concerned by these proposals, which are likely to be used to stifle criticism of the government.

“Around the world from Cuba to Indonesia and Uganda, artists are being pressured by governments seeking to control their art and their message. These misplaced efforts are an intolerable intrusion into artistic freedom and must not be enacted,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index said.

Signatories to the letter include U2’s Bono and Adam Clayton, author Wole Soyinka, and Razorlight’s Johnny Borrell.

Full text of the letter follows:

Uganda’s government is proposing regulations that include vetting new songs, videos and film scripts, prior to their release. Musicians, producers, promoters, filmmakers and all other artists will also have to register with the government and obtain a licence that can be revoked for a range of violations.

We, the undersigned, are deeply concerned by these proposals, which are likely to be used to stifle criticism of the government.

We, the undersigned, vehemently oppose the draconian legislation currently being prepared by the Ugandan government that will curtail the freedom of expression in the creative arts of all musicians, producers and filmmakers in the country.

The planned legislation includes:

- All Ugandan artists and filmmakers required to register and obtain a licence, revokable for any perceived infraction.

- Artists required to submit lyrics for songs and scripts for film and stage performances to authorities to be vetted.

- Content deemed to contain offensive language, to be lewd or to copy someone else’s work will be censured.

- Musicians will also have to seek government permission to perform outside Uganda.

Contained in a 14 page draft Bill that bypasses Parliament and will come before Cabinet alone in March to be passed into law, any artist, producer or promoter who is considered to be in breach of its guidelines shall have his/her certificate revoked.

This proposed legislation is in direct contravention of Clause 29 1a b of the Ugandan

Constitution which states:

- Protection of freedom of conscience, expression, movement, religion,

assembly and association.

(1) Every person shall have the right to—

(a) Freedom of speech and expression which shall include freedom of the media;

(b) Freedom of thought, conscience and belief which shall include academic

freedom in institutions of learning;

Furthermore, in accordance with Clause 40 (2)

(2) Every person in Uganda has the right to practise his or her profession and to

carry on any lawful occupation, trade or business.

As a Member State of the African Union, the Republic of Uganda has ratified the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Article 9 of the Charter provides:

- Every individual shall have the right to receive information.

- Every individual shall have the right to express and disseminate his opinions within the law.

We therefore call upon the Ugandan government to end this grievous and blatant

violation of the constitutional rights of Ugandan artists and producers, and to honour

its international obligations as laid down in the various international human rights

conventions to which Uganda is a signatory and for Uganda to uphold freedom of speech.

Background

- Although freedom of expression is protected under the Uganda constitution, it is coming under increasing threat in the country.

- In 2018, authorities arrested popular musician and opposition member of parliament, Robert Kyagulanyi, better known as Bobi Wine. He was badly beaten in military custody. Musicians, writers and social activists including Chris Martin, Angelique Kidjo, U2’s The Edge, Damon Albarn and Wole Soyinka, signed a petition calling for his release, which ultimately succeeded.

- Since July 1, Ugandans have had to pay a tax of 200 shillings, about 5 US cents, for every day they use services including Facebook, Twitter, Skype and WhatsApp.

- The government said it wanted to regulate online gossip, or idle talk but critics fear this meant it wanted to censor opponents.

- During the presidential election in 2016, officials blocked access to Facebook and Twitter

- On Thursday January 31 a statement was made by Jeremy Hunt MP, the UK’s Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs: “”We are aware of the proposed regulations to the Ugandan music and entertainment industry that are currently being consulted on and are yet to be approved by the Cabinet. The UK’s position is that such regulations must not be used as a means of censorship. The UK supports freedom of expression as a fundamental human right and, alongside freedom of the media, maintains that it is an essential quality of any functioning democracy. We continue to raise any concerns around civic and political issues directly with the Ugandan government.”

ABTEX – Producer, Uganda

ADAM CLAYTON – Musician, U2

ALEX SOBEL – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

AMY TAN – Novelist, Screenwriter

ANDY HEINTZ – Freelance journalist and author, USA

ANISH KAPOOR – Artist, United Kingdom

ANN ADEKE – Member of Parliament, Uganda

ANNU PALAKUNNATHU MATTHEW – Artist, USA and India

ASUMAN BASALIRWA – Member of Parliament, Uganda

AYELET WALDMAN – Writer

BELINDA ATIM – Uganda Sustainable Development Initiative

BILL SHIPSEY – Founder, Art for Amnesty

BONO – Musician, U2

BRIAN ENO – Artist, Musician and Producer

BRUCE ANDERSON – Journalist Editor/Publisher

CLAUDIO CAMBON – Artist/Translator, France

CRISPIN BLUNT – Member of Parliament and former Chair of Foreign Affairs Select Committee, United Kingdom

DAN MAGIC – Producer, Uganda

DANIEL HANDLER – Writer, Musician aka Lemony Snicket

DAVID FLOWER – Director, Sasa Music

DAVID HARE – Playwright

DAVID SANCHEZ – Saxophonist and Grammy Winner

DEBORAH BRUGUERA – Activist, Italy

DELE SOSIMI – Musician – The Afrobeat Orchestra

DOCTOR HILDERMAN – Artist, Uganda

DR VINCENT MAGOMBE – Journalist and Broadcaster

DR PAUL WILLIAMS – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

EDDIE HATITYE – Director, Music In Africa

EDDY KENZO – Artist, Uganda

EDWARD SIMON – Musician and Composer, Venezuela

EFE OMOROGBE – Director Hypertek, Nigeria

ERIAS LUKWAGO – Lord Mayor of Kampala Uganda

ELYSE PIGNOLET – Visual Artist, USA

ERIC HARLAND – Musician

FEMI ANIKULAPO KUTI – Musician, Nigeria

FEMI FALANA – Human Rights Lawyer, Nigeria

FRANCIS ZAAKE – Member of Parliament, Uganda

FRANK RYNNE – Senior Lecturer British Studies, UCP, France

GARY LUCAS – Musician

GERALD KARUHANGA – Member of Parliament, Uganda

GINNY SUSS – Manager, Producer

HELEN EPSTEIN – Professor of Journalism Bard College

HENRY LOUIS GATES – Director of the Hutchins Center at Harvard University

HUGH CORNWELL – Musician

IAIN NEWTON – Marketing Consultant

INNOCENT (2BABA) IDIBIA – Artist, Nigeria

IRENE NAMATOVU – Artist, Uganda

IRENE NTALE – Artist, Uganda

JANE CORNWELL – Journalist

JEFFREY KOENIG – Partner, Serling Rooks Hunter McKoy Worob & Averill LLP

JESSE RIBOT – American University School of International Service

JIM GOLDBERG – Photographer, Professor Emeritus at California College of the Arts

JODIE GINSBERG – CEO, Index on Censorship

JOEL SSENYONYI – Journalist, Uganda

JON FAWCETT – Cultural Events Producer

JON SACK – Artist

JOHN AJAH – CEO, Spinlet

JOHN CARRUTHERS – Music Executive

JOHN GROGAN – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

JONATHAN LETHEM – Novelist

JONATHAN MOSCONE – Theater Director

JONATHAN PATTINSON – Co-Founder Reluctantly Brave

JOHNNY BORRELL – Singer, Razorlight

JOJO MEYER – Musician

KADIALY KOUYATE – Musician, Senegal

KALUNDI SERUMAGA – Former Director – Uganda National Cultural Centre/National Theatre

KASIANO WADRI – Member of Parliament, Uganda

KEITH RICHARDS OBE – Writer

KEMIYONDO COUTINHO – Filmmaker, Uganda

KENNETH OLUMUYIWA THARP CBE – Director The Africa Centre

KING SAHA – Artist, Uganda

KWEKU MANDELA – Filmmaker

LAUREN ROTH DE WOLF – Music Manager Orchestra of Syrian Musicians

LEMI GHARIOKWU – Visual Artist, Nigeria

LEO ABRAHAMS – Producer, Musician, Composer

LES CLAYPOOL – Musician, Primus

LINDA HANN – MD Linda Hann Consulting Group

LUCIE MASSEY – Creative Producer

LUCY DURAN – Professor of Music at SOAS University of London

LYNDALL STEIN – Activist/Campaigner, United Kingdom

MARC RIBOT – Musician

MARCUS DRAVS – Producer

MAREK FUCHS – MD Sauti Sol Entertainment, Kenya

MARGARET ATWOOD – Author

MARK LEVINE – Professor of History UC Irvine – Grammy winning artist

MARY GLINDON – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

MATT PENMAN – Musician, New Zealand

MARTIN GOLDSCHMIDT – Chairman, Cooking Vinyl Group

MEDARD SSEGONA – Member of Parliament, Uganda

MICHAEL CHABON – Writer

MICHAEL LEUFFEN – NTS Host, Carhartt WIP Music Rep

MICHAEL UWEDEMEDIMO – Director, CMAP and Research Fellow King’s College London

MILTON ALLIMADI – Publisher, The Black Star News

MORGAN MARGOLIS – President, Knitting Factory Entertainment, USA

MOUSTAPHA DIOP – Musician, Senegal MusikBi CEO

MR EAZI – Musician, Producer, Nigeria

MUWANGA KIVUMBI – Member of Parliament, Uganda

NAOMI WEBB – Executive Director, Good Chance Theatre, United Kingdom

NICK GOLD – Owner, World Circuit Records

NUBIAN LI – Artist, Uganda

OHAL GRIETZER – Composer

OBED CALVAIRE – Musician

OMOYELE SOWORE – Founder Sahara Reporters and Nigerian Presidential Candidate

PATRICK GRADY – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

PAUL MAHEKE – Artist, United Kingdom

PAUL MWIRU – Member of Parliament, Uganda

PETER GABRIEL – Musician

RACHEL SPENCE – Arts Writer and Poet, United Kingdom

RASHEED ARAEEN – Artist, United Kingdom

RAYMOND MUJUNI – Journalist, Uganda

RHETT MILLER – Musician, Writer

RILIWAN SALAM – Artist Manager

ROBERT MAILER ANDERSON – Writer and Producer

ROBIN DENSELOW – Journalist, United Kingdom

ROBIN EUBANKS – Trombonist, Composer, Educator

ROBIN RIMBAUD – Musician

RUTH DANIEL – CEO, In Place of War

SAMIRA BIN SHARIFU – DJ

SANDOW BIRK – Visual Artist, USA

SANDRA IZSADORE – Author, Artist, Activist, USA

SEAN JONES – Musician, Composer, Bandleader, Educator

SEBASTIAN ROCHFORD – Musician, Pola Bear

SEUN ANIKULAPO KUTI – Musician, Composer

SHAHIDUL ALAM – Photojournalist and Activist, Bangladesh

SIDNEY SULE – B.A.H.D Guys Entertainment Management, Nigeria

SIMON WOLF – Senior Associate, Amsterdam & Partners LLP

SRIRAK PLIPAT – Executive Director, Freemuse

STEPHEN BUDD – OneFest / Stephen Budd Music Ltd

SOFIA KARIM – Architect and Artist

STEPHEN HENDEL – Kalakuta Sunrise LLC

STEVE JONES – Musician and Producer

SUZANNE NOSSEL – CEO, PEN America

TANIA BRUGUERA – Artist and Activist, Cuba

TOM CAIRNES – Co-Founder Freetown Music Festival

WOLE SOYINKA – Nobel Laureate, Nigeria

YENI ANIKULAPO KUTI – Co-Executor of the Fela Anikulapo Kuti Estate

ZENA WHITE – MD, Knitting Factory and Partisan Records

31 Jan 2019 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns -- Featured, Middle East and North Africa

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Michelle Bachelet, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Credit: UN Women / Flickr

H.E. Michelle Bachelet

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)

United Nations

52 Rue des Paquis

1201 Geneva, Switzerland

Your Excellency,

We, the undersigned organisations, write to you to express our concern regarding the worsening situation for civil society in Bahrain. We believe co-ordinated international action coupled with public scrutiny are imperative to address the government of Bahrain’s ongoing attacks on civil society and to hold the kingdom accountable to its commitments to international human rights laws and standards. To this end, we call upon your Office to continue to monitor the situation in Bahrain and to continue to raise concerns at the highest level, both publicly and privately, with the government, as was done by your predecessor, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein. We believe heightened scrutiny of Bahrain’s human rights record and its ongoing human rights violations is particularly important now that the kingdom is a Member State of the Human Rights Council.

In the past two years, the Bahraini government increased its repression of the kingdom’s remaining civil society organisations, political opposition groups, and human rights defenders. In June 2016, Bahrain’s Administrative Court forcibly dissolved al-Wefaq, Bahrain’s largest political opposition society, a ruling that was upheld in February 2018. In May 2017, a court approved the forcible dissolution of the National Democratic Action Society, also known as Wa’ad. Only a month later, the government indefinitely suspended the kingdom’s last remaining independent newspaper, Al-Wasat, continuing its repression of free expression and press freedom.

While there were hopes that the government might ease repression in the run-up to elections for the lower house of parliament on 24 November 2018, these were dashed with a series of actions and policies that effectively precluded the elections from being free or fair, and that continued the broader assault on civil society. Only weeks ahead of ahead of the elections, the country’s highest appeals court sentenced Sheikh Ali Salman, the Secretary-General of Al-Wefaq, to life in prison on spurious charges of espionage dating from 2011. The government also enacted new legislation banning all individuals who had ever belonged to a dissolved political society from seeking or holding elected office, as well as anyone who has ever served six months or more in prison. This affects a large portion of Bahrain’s population, as the kingdom currently has around 4,000 political prisoners.

Beyond rigging the election process at the expense of political opposition societies and free and fair participation, over this past year Bahrain has continued to target, harass, and imprison activists and human rights defenders for exercising their right to free expression. The government criminalised calls to boycott the elections, and, on 13 November 2018, arrested former Member of Parliament Ali Rasheed al-Asheeri for tweeting about boycotting the November elections. On 31 December 2018, Bahrain’s Court of Cassation – its court of last resort – upheld prominent human rights defender Nabeel Rajab’s five-year prison sentence on spurious charges of tweeting and re-tweeting criticism of torture in Jau Prison and the war in Yemen, drawing criticism from the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. With this decision, Rajab has exhausted all legal remedies to reverse the charges and will remain in prison until 2023. He has already served a two-year prison sentence on charges related to television interviews in which he discussed the human rights situation in the kingdom.

While Bahrain has several institutions tasked with oversight responsibilities and enforcing accountability for human rights abuses, we have grave concerns over their effectiveness, their independence, and their commitment to fulfilling their mandates. Similar concerns have been raised about other Bahraini institutions – the National Institution for Human Rights (NIHR) and the Ministry of Interior Ombudsman – by the UN Human Rights Committee. In the Committee’s first evaluation of Bahrain under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) in July 2018, it found the NIHR largely lacked sufficient independence from the government. The European Parliament has also criticised the NIHR, including in a June 2018 resolution where the body expressed “regret” for the honours it has bestowed upon the NIHR. In the resolution, the European Parliament cited the institution’s lack of independence to fulfil its duties. The Ministry of Interior (MoI) Ombudsman has received sharp criticism, including from the UN Committee Against Torture (CAT). The CAT cited the Ombudsman’s lack of independence, impartiality, and efficacy in addressing complaints submitted to the institution.

Bahrain’s national institutions not only fail to implement human rights reforms, they help perpetuate and whitewash abuses. Both the Ombudsman and NIHR have released reports that sanitise violations like police brutality, while neglecting to address or condemn violent police raids on peaceful protests.

The failure of Bahrain’s human rights institutions to address serious abuses both reflects and promotes a broader culture of impunity in the country, where the government can continue to suppress free expression and civil society.

Despite these abuses and despite concerns from UN bodies, Bahrain has not been the subject of collective action in the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) since a joint statement in September 2015 at HRC 30. Since then, the government has taken increased steps to limit fundamental freedoms, including restricting the rights to free expression, free assembly, free association, and free press, dissolving political opposition societies and jailing human rights defenders, religious leaders, and political figures. However, even as Bahrain has embarked on this campaign to suppress opposition and dissent, state action on Bahrain in the HRC has been limited to individual condemnations by various governments under Agenda Items 2 and 4.

Despite this lack of joint action, the Office of the High Commissioner has been consistently vocal about Bahrain’s rights abuses, and we are very appreciative of the Office’s attention over the past several years. Your predecessor raised concerns about Bahrain in his opening statements at the HRC, including at the 36th Council session, where he highlighted restrictions on civil society and the kingdom’s lack of engagement with international human rights mechanisms, and at 38th Council session, in which he reiterated past concerns and sharply criticised Bahrain for its continued refusal to co-operate with the Office of the High Commissioner and the mandates of the Special Procedures.

We believe that this UN scrutiny is now even more necessary as Bahrain assumes a seat on the Council as a Member State.

We strongly urge you to continue to monitor the situation, to publicly express your concerns to Bahraini officials, and to call on the Bahraini government to meet its international obligations, including those concerning protecting and promoting civil society. Without an independent, viable civil society in the country there can be no serious domestic pressure on the government to relax restrictions and ease repression.

We call on you to highlight Bahrain’s restrictions on civil society, targeting of human rights defenders, dissolution of political opposition, and unrelenting attacks on free expression in your opening statement at the 40th Human Rights Council session, the first session of which Bahrain is a member of the Council.

Sincerely,

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

ARTICLE 19

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS)

Cartoonists Rights Network International (CRNI)

Center for Media Studies & Peace Building (CEMESP)

Centre for Independent Journalism (CIJ)

Foro de Periodismo Argentino

Freedom Forum

Independent Journalism Center (IJC)

Index on Censorship

Initiative for Freedom of Expression – Turkey

Maharat Foundation

Mediacentar Sarajevo

Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA)

Norwegian PEN

OpenMedia

Pacific Islands News Association (PINA)

PEN America

Southeast Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA)

South East Europe Media Organisation

Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM)

Vigilance for Democracy and the Civic State

Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC)

Association for Human Rights in Ethiopia (AHRE)

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy

Cairo Institute to Human Rights Studies (CIHRS)

CIVICUS

European Centre for Democracy and Human Rights

Odhikar (Bangladesh)

Center for Civil Liberties (Ukraine)

Sudanese Development Initiative (Sudan)

JOINT Liga de ONGs em Mocambique

West African Human Rights Defenders Network

Latin American Network for Democracy (REDLAD)

Ligue Burundaise des Droits de l’homme ITEKA

Organisation Tchadienne Anti-Corruption (OTAC)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1549278314945-d1d5bcda-455e-2″ taxonomies=”716″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Dec 2018 | Artistic Freedom, Cuba, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The artist Tania Bruguera who was detained last week with fellow artists in Cuba for protesting against Decree 349, an artistic censorship law, has written an open letter explaining why she will not attend Kochi biennial at a time that is crucial for freedom of expression in Cuba and beyond.

Bruguera who was due to attend Kochi states in the letter:

“At this moment I do not feel comfortable traveling to participate in an international art event when the future of the arts and artists in Cuba is at risk… As an artist I feel my duty today is not to exhibit my work at an international exhibition and further my personal artistic career but to expose the vulnerability of Cuban artists today.”

Bruguera feels it is important to highlight the situation in Cuba and also to see it as part of a global phenomenon of repression of artists and freedom of expression. Recent cases such as Shahidul Alam, the photographer imprisoned by the government of Bangladesh (who Bruguera campaigned for by hosting two protest shows at Tate Modern in October), the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi killed in the Saudi embassy in Turkey, and photographer Lu Guang who has gone missing in China, demonstrate that governments feel emboldened to openly attack high profile figures, moving beyond internal state repression which used to happen behind closed doors.

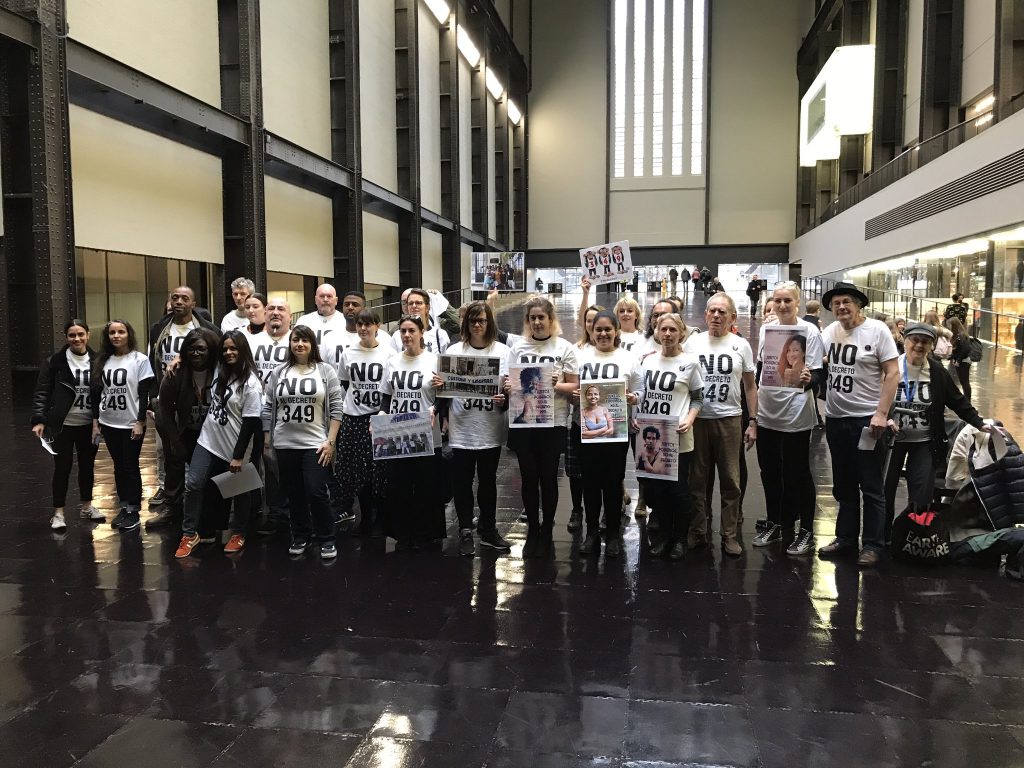

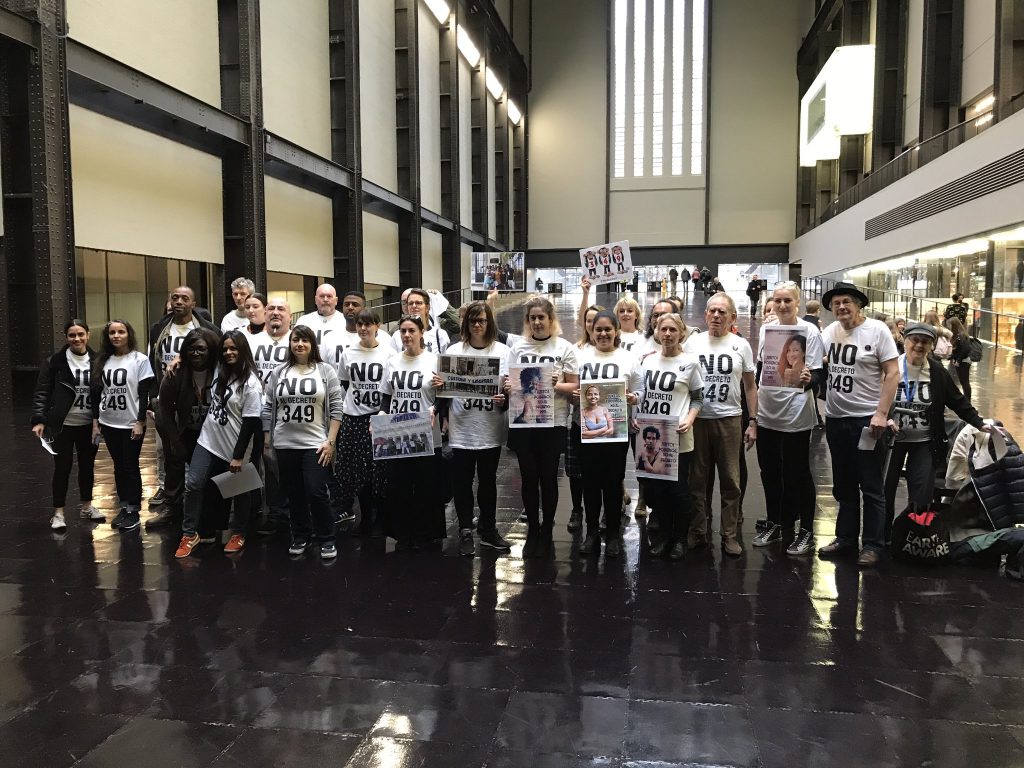

On Wednesday 5 December supporters of Bruguera held a protest exhibition at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, where participants spoke on a microphone about Decree 349 and the abuse of artists around the world. Alistair Hudson, director of the Whitworth and Manchester Art Gallery spoke at the event via live phone in. Tate director Maria Balshaw, also spoke out on the BBC news broadcast of the Turner Prize whilst Tate Modern director Frances Morris made a statement on Tate twitter. A speech by HRH Prince Constantijn on the occasion of the 2018 Prince Claus Awards at the Royal Palace, Amsterdam on 6 December 2018 also spoke about the situation with reference to Tania Bruguera, Shahidul Alam and Lu Guang. Many other cultural institutions around the world have also made public statements, whilst others are showing signs that they will follow.

The hope is that art institutions and events around the world, such as Kochi biennial, follow suit and show open solidarity to defend the artists’ space.

The full wording of Bruguera’s letter is as follows:

OPEN LETTER BY TANIA BRUGUERA TO THE DIRECTOR OF KOCHI BIENNALE ON DECREE 349

At this moment I do not feel comfortable traveling to participate in an international art event when the future of the arts and artists in Cuba is at risk. The Cuban government with Decree 349 is legalizing censorship, saying that art must be created to suit their ethic and cultural values (which are not actually defined). The government is creating a `cultural police´ in the figure of the inspectors, turning what was until now, subjective and debatable into crime.

Cuban artists have united for the first time in many decades to be heard, each with their own points of view. They had meetings with bureaucrats from the Ministry of Culture who promised them that they would meet again to give them answers. Instead, the Minister and other bureaucrats appeared on TV and made comments such as “[those who oppose Decree 349] want the dissolution of the institution” and “the alternative they are proposing is the commercialisation of art.”

Nothing could be further from the truth. If this were true, the artists would not have written to the institutions and sought dialogue with them.

But, a public opinion campaign by the government against the artists, with the intention to divide between “good ones” and “bad ones”, has started. This is even more concerning when under this decree the law restricts but provides no guarantee of whether an artist will or will not be criminalized or not at any time.. Moreover, the decree states that all `artistic services´ must be authorized by the Ministry of Culture and its correspondent institutions, making independent art impossible.

The last time a decree of this sort was enacted was the no. 226 from November 29 of 1997, which is evidence of the long life that such a decree could have and its long term impact on our culture.

As an artist I feel my duty today is not to exhibit my work at an international exhibition and further my personal artistic career but to be with my fellow Cuban artists and to expose the vulnerability of Cuban artists today.

We are all waiting for the regulations and norms the Ministry of Culture will put forward to implement Decree 349 in the hope that they include the suggestions and demands so many artists shared with them. I would like to add that the instructor from the Ministry of Interior who is in charge of my case menaced me yesterday, saying that if I didn’t leave Cuba and if I did `something´, I would not be able to leave in the future.

Injustice exists because previous injustices were not challenged.

Ironically, I’m sending you this text on December 10th the International Day of Human Rights.

Un abrazo,

Tania Bruguera[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1544431942749-6dbcba3e-bd36-2″ taxonomies=”15469, 7874″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Dec 2018 | Artistic Freedom, Awards, Cuba, Fellowship, Fellowship 2019, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Update: All arrested artists have now been released, although they remain under police surveillance. Cuba’s vice minister of culture Fernando Rojas has declared to the Associated Press that changes will be made to Decree 349 but has not opened dialogue with the artists involved in the campaign against the decree.

Index on Censorship joined others at the Tate Modern on 5 December in a show of solidarity with those artists arrested in Cuba for peacefully protesting Decree 349, a law that will severely limit artistic freedom in the country. Decree 349 will see all artists — including collectives, musicians and performers — prohibited from operating in public places without prior approval from the Ministry of Culture.

In all, 13 artists were arrested over 48 hours. Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, members of the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-winning Museum of Dissidence, were arrested in Havana on 3 December. They are being held at Vivac prison on the outskirts of Havana. The Cuban performance artist Tania Bruguera, who was in residency at the Tate Modern in October 2018, was arrested separately, released and re-arrested. Of all those arrested, only Otero Alcantara, Nuñez Leyva and Bruguera remain in custody.

Index on Censorship’s Perla Hinojosa speaking at the Tate Modern.

Speaking at the Tate Modern, Index on Censorship’s fellowships and advocacy officer Perla Hinojosa, who has had the pleasure of working with Otero Alcantara and Nuñez Leyva, said: “We call on the Cuban government to let them know that we are watching them, we’re holding them accountable, and they must release artists who are in prison at this time and that they must drop Decree 349. Freedom of expression should not be criminalised. Art should not be criminalised. In the words of Luis Manuel, who emailed me on Sunday just before he went to prison: ‘349 is the image of censorship and repression of Cuban art and culture, and an example of the exercise of state control over its citizens’.”

Other speakers included Achim Borchardt-Hume, director of exhibitions at Tate, Jota Castro, a Dublin-based Franco-Peruvian artist, Sofia Karim, a Lonon-based architect and niece of the jailed Bangladeshi photojournalist Shahidul Alam, Alistair Hudson, director of Manchester Art Gallery and The Whitworth, and Colette Bailey, Artistic director and chief executive of Metal, the Southend-on-Sea-based arts charity.

Some read from a joint statement: “We are here in London, able to speak freely without fear. We must not take that for granted.”

It continued: “Following the recent detention of Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam along with the recent murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, there us a global acceleration of censorship and repression of artists, journalists and academics. During these intrinsically linked turbulent times, we must join together to defend our right to debate, communicate and support one another.”

Castro read in Spanish from an open declaration for all artists campaigning against the Decree 349. It stated: “Art as a utilitarian artefact not only contravenes the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Cuba is an active member of the United Nations Organisation), but also the basic principles of the United Nations for Education, Science and Culture (UNESCO).”

It continued: “Freedom of creation, a basic human expression, is becoming a “problematic” issue for many governments in the world. A degradation of fundamental rights is evident not only in the unfair detention of internationally recognised creatives, but mainly in attacking the fundamental rights of every single creator. Their strategy, based on the construction of a legal framework, constrains basic fundamental human rights that are inalienable such as freedom of speech. This problem occurs today on a global scale and should concern us all.”

Cuban artists Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, members of the Index-award winning Museum of Dissidence

Mohamed Sameh, from the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-winning Egypt Commission on Rights and Freedoms, offered these words of solidarity: “We are shocked to know of Yanelys and Luis Manuels’s detention. Is this the best Cuba can do to these wonderful artists? What happened to Cuba that once stood together with Nelson Mandela? We call on and ask the Cuban authorities to release Yanelys and Luis Manuel immediately. The Cuban authorities shall be held responsible of any harm that may happen to them during this shameful detention.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1544112913087-f4e25fac-3439-10″ taxonomies=”23772″][/vc_column][/vc_row]