17 Mar 2017 | Academic Freedom, Digital Freedom, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Many universities pay lip service to freedom of speech on campus, but actions often tell a different story. In an effort to limit insult and offence, universities also limit freedom of expression. Spiked’s survey of British universities examines the policies and actions of faculty and students and ranks them using a traffic-light-themed system.

A ranking of “red” means that the university in question has banned and actively censored ideas on campus, “amber” signifies that it as chilled free speech through intervention and “green” indicates that the university has a hands-off approach to free speech. Over the last three years, the Spiked’s analysis has seen the steady decline of free speech on campus.

Here are just three examples from the last few weeks.

Lincoln University Conservative Society censored for criticising state of free speech on campus

The Lincoln University Conservative Society has been suspended from using social media by the Lincoln Student Union after publishing tweets that highlighted the university’s lack of free speech.

“Due to SU orders this Twitter account will no longer be active. We hope to return on 1st May. Sorry for any inconvenience,” the Conservative Society tweeted after a students’ union disciplinary hearing found that two tweets by the society brought the university into “disrepute.”

One tweet complained about a questionnaire those who wish to run in student union elections are required to submit. The other included a screenshot of a Spiked article which gave Lincoln the worst possible Free Speech University Ranking. According to Spiked, the university administration has a better ranking and therefore less restrictive free speech policies than the students’ union. The union’s policies allow them to restrict what they deem to be offensive, racist or fascist speech, and ban speakers who may draw controversy as part of their Safe Campus policy.

This is not the first time the students’ union has been criticised for violating students’ right to free speech. In 2016 it has banned use of the social media app Yik Yak from campus. The app, which allows students to post anonymous comments based on location, was made unavailable on the university’s wifi networks because it “caused much distress to a number of students”.

After the decision to suspend the Conservative Society’s Twitter account, , the union published a statement expressing their support and dedication to free speech on campus.

“Freedom of speech is a fundamental value of the Students’ Union,” it said. “The SU is built on a foundation where students can express opinions and ideas freely within the law.”

A spokesperson for the Conservative Society told The Lincolnite that the decisions were “misguided and disproportionate”.

Karl McCartney, MP for Lincoln, called the shutdown “intolerant,” “totalitarian,” and like “something out of the Soviet Union or North Korea”.

Tommy Robinson unwelcome at Oxford Brookes University

Ex-English Defence League leader Tommy Robinson was due to speak at Oxford Brookes University in February. Following an outcry from members of the student body, the university’s student union refused approval of the event, disallowing the right-wing activist to speak on campus.

Robinson, who is also at the helm of the anti-Islamist group Pegida UK, had been invited to speak at the university by an anti-extremism student group. The opposition to Robinson’s appearance on campus was strong enough that the police warned it posed a “public disorder” risk.

Accusations of Robinson supporting fascism and white supremacy spread throughout the university campus. Aspiring protesters launched a petition claiming that “regardless of his official departure from the EDL in 2013, Robinson has built his career on Islamophobic, racist speech and violence”.

The liberal student organisation that originally invited Robinson to speak did so in an effort to combat extremism through open dialogue.

Oxford Brookes University places no significant restrictions on free speech, but its students’ union employs a No Platform policy for those it deems to be fascist or racist, as well as a de facto ban on sexist expression.

Spiked gives Oxford Brookes an overall rating of amber, a combination of a green rating for the university and a red rating for the students’ union.

Cardiff Metropolitan University accused of policing speech in the name of equality

Cardiff Metropolitan University is attempting to “promote an atmosphere in which all students and staff feel valued”. In doing so, the university has created a Code of Practice on using Inclusive Language that enforces acceptable terminology throughout its academic programmes and campus.

The code offers “a few suggestions” – a list of 34 words and phrases to avoid and what to replace them with. If “this Code is not adhered to” disciplinary procedures can be taken against both staff and students.

Some of these suggestions include avoiding assumptions and generalisations based on stereotypes or norms from one’s own cultural background, using gender-neutral language, abstaining from using terms which might be regarded as patronising or pitying and using language which embraces cultural diversity.

On its “gender-neutral” terms checklist, the university recommends replacing the expression “right-hand man” with “chief assistant,” using “fairness, good humour, or sense of fair play” in place of “sportsmanship,” saying “artificial, manufactured, or synthetic” instead of “manmade” and calling adult females “women” instead of “girls”.

The code also states: “These days the terms ‘homosexual’ and ‘heterosexual’ seem laden with the values of a previous time. Referring to ‘same-sex’ and ‘other-sex’ relationships is a good option.”

Spiked has given Cardiff Metropolitan University an amber rating as it places restrictions on “offensive comments or gestures” and “jokes,” while also urging students to police their speech and avoid non-inclusive words. The students’ union has a rating of red due to its no platform policy, which bans racists, sexists and homophobes from the campus.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1489746234747-41452242-9ad6-6″ taxonomies=”8843″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Dec 2016 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 45.04 Winter 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Contributors include Lily Cole, Daphne Selfe, Linda Grant, Bibi Russell, Katy Werlin, Jang Jin-sung, Maggie Alderson and Eliza Vitri Handayani”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at fashion and how people both express freedom through what they wear. But it also looks at how women in particular have their freedom of expression curtailed by rigid dress codes – whether they are women in Saudi Arabia who have to wear abayas by law or women in the UK and Canada whose employers insist they wear high heels shoes.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”82377″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Models Lily Cole and Daphne Selfe discuss why changes in society are reflected in the clothes we (are allowed) to wear. Maggie Alderson, former editor of Elle describes how she was arrested for being a punk rocker in the 1970s, while Eliza Vitri Handayani talks about how punks in Indonesia today are still persecuted for what they wear and how they look. Nigerian model and journalist Wana Udobang riffs on fashion in Nigeria and how she was snubbed by bouncers and waiters at a wedding for wearing the wrong clothes.

Ismail Einashe describes how traditional dress can be life-threatening for Oromos in Ethiopa, while Magela Baudoin delves into class and ethnic gradations in Bolivia and reveals that the way some women dress means they are discriminated against. Novelist Linda Grant describes how her Jewish immigrant parents used the way they dressed to try and fit into middle-class British society. Meanwhile Katy Werlin gives a historical perspective as she discusses how the 18th century French revolutionaries, known as sans-culottes, celebrated their peasant clothes as they overthrew the aristocratic regime.

Martin Rowson brings another perspective to fashion in his new cartoon which depicts a catwalk on which despots show off their latest costumes. Spot President-elect Donald Trump sporting a furry thong. Trump is also in US media expert Eric Alterman’s sights as he describes why journalists in the USA believe the new president will seek to challenge media freedoms guaranteed by the constitution. Turkish researchers Burak Bilgehan Özpek and Başak Yavcan investigate how the Turkish government is using state advertising to control the media.

We also publish an interview with Turkish intellectual, linguist and founder of a mathematics village Sevan Nişanyan. Our reporter communicated with him using notes smuggled out from the prison where he is serving a 16-year sentence on charges connected with freedom of speech. The culture section includes poems from a former North Korean propagandist Jang Jin-sung who defected to the South and now runs a website smuggling news out of North Korea. We also carry poems about the extraordinariness of everyday life from Brazilian author Paulo Scott and a never before seen English translation of a short story by legendary Argentine writer Haroldo Conti.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: FASHION RULES” css=”.vc_custom_1481731933773{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Dressing to oppress: why dress codes and freedom clash

The censors’ new clothes, by Rachael Jolley: Freedom is not about the amount of clothing you put on or take off, but about having the choice to do so

Fashion police, by Natasha Joseph: Some feel the miniskirt is a threat to the state in Uganda and women are getting attacked for wearing it

Wearing a T-shirt got me arrested, by

Maggie Alderson: Wearing punk clothes in 1970s London was dangerous, but now British teenagers can wear anything

Colour bars, by Magela Baudoin: Traditional clothing is still a sign of social status in Bolivia and wearing such clothes often leads to discrimination

Models of freedom, by Bibi Russell: Bangladeshi women are now vital to the economy but they are still restricted in their dress

The big cover-up, by Laura Silvia Battaglia: Women in Saudi Arabia and Yemen test how far they can customise what they are allowed to wear. Translation by Lucinda Byatt

Rebel with a totally fashionable cause, by Wana Udobang: A Nigerian model refuses to conform to stifling social expectations and sees the consequences

Stripsearch cartoon, by Martin Rowson: A fetching new range of despotwear

Ethiopia in crisis, closes down news, by Ismail Einashe The Oromo people use traditional clothing as a symbol of resistance and it is costing them their lives

Baggy trousers are revolting

, by Katy Werlin: The sans-culottes of the French revolution transformed peasant dress into a badge of honour

Muslim punks in mohawks attacked, by Eliza Vitri Handayani: Punks in Indonesia are persecuted but still manage to maintain a culture which stands up for difference

Design is the limit, by Jemimah Steinfeld: China is loosening up on personal freedoms including fashion, but designers still face some constraints

A modest proposal, by Kaya Genç: “Modest” dress codes are all the rage in Turkey as some turn their backs on the legacy of Atatürk

Uniformity rules, by Jan Fox: Prisoners often try to customise their uniforms but does stripping individuality make rehabilitation more difficult?

Keeping up appearances, by Linda Grant: Linda Grant’s immigrant family were upwardly mobile and bought clothes that showed their aspirations

Sewing it up, by Rachael Jolley: At 88 Daphne Selfe is Britain’s oldest supermodel. She talks about how fashion has changed in her lifetime

Style counsels, by Kieran Etoria-King: Model, activist and actor Lily Cole talks about how school girls customise their uniforms to give them a sense of individuality

Tall stories, by Sally Gimson: Wearing high heels is a way for some women to express freedom, while for others it’s a form of oppression

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Challenging media, by Eric Alterman: If his campaign is anything to go by, President Trump is likely to restrict freedom of the press

Living in limbo, by Marco Salustro: A journalist reveals the challenges of reporting from inhumane migrant detention camps in Libya

Follow the money, by

Burak Bilgehan Özpek and Başak Yavcan: The Turkish government is rewarding newspapers which favour its position with more state-sponsored advertising

Fighting for our festival

freedoms, by Peter Florence: Mutilated bodies, petitions and a citizen’s arrest: the director of the Hay literary festivals describes the trials and tribulations of his job

Barring the bard, by Jennifer Leong: Actor Jennifer Leong on confronting attempts to censor performances of Shakespeare around the world

Assessing Correa’s free

speech heritage, by Irene Caselli: The Ecuadorian president’s record on free speech is reviewed as his term in office comes to an end. He gave sanctuary to Wikileaks founder, Julian Assange, in the country’s London embassy but brought in restrictive media laws at home

Framed as spies, by Steven Borowiec: South Korean journalist Choi Seung-ho hit a national nerve when he exposed the security services for framing ordinary citizens as North Korean spies

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Back from the Amazon, by

Paulo Scott: Newly translated poems from Scott’s acclaimed collection, Even Without Money I Bought a New Skateboard. Interview by Kieran Etoria-King. Poems translated by Stefan Tobler

A story from the disappeared, by Haroldo Conti: Jon Lindsay Miles introduces a poignant short story, published in English for the first time, by the award- winning Argentine writer who disappeared in 1976. Translation also by Jon Lindsay Miles

Poems for Kim, by Jang Jin-sung: North Korean propagandist poet turned high profile defector talks about life within the world’s most secretive country. Interview by Sybil Jones

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view, by Jodie Ginsberg: Face-to-face encounters are still important and governments worldwide know that restricting travel continues to be an effective way of stifling voices

Index around the world, by

Kieran Etoria-King: Coverage of Index’s work over the last few months including exposing the difficulties of war reporting and our Mapping Media Freedom project

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Where’s our president? by

Kiri Kankhwende: Malawi’s journalists tease their president as part of a campaign to make the government more transparent

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

28 Sep 2016 | mobile, News

Monday marked the beginning of Banned Books Week. To celebrate the freedom to read, Index on Censorship staff explore some of their favourite, and some of the most important, banned or challenged books.

Ryan McChrystal – Borstal Boy by Brendan Behan

Brendan Behan’s autobiographical work Borstal Boy was banned in Ireland in December 1958. His London publisher, Hutchinson’s, had sent a batch of copies to Dublin to be sold at a Christmas market but they were confiscated at the port. Behan was outraged that a group of “country yobs” could prevent the distribution of his book.

Borstal Boy is the story of how a 16-year-old Behan landed himself in a series of institutions for young offenders in Kent, having been charged with membership of the IRA, and what happened to him after that.

Although Ireland’s Censorship of Publications Board never explained why the book was banned, it probably had something to do with its depictions of adolescents talking about sex and its pillorying of Irish social attitudes, republicanism and the Catholic Church. The board is, after all, known for its stringent adherence to Roman Catholic values.

When Behan later learned that the book was also banned in Australia and New Zealand, he took solace in song and humour as he went around Dublin singing:

“My name is Brendan Behan, I’m the latest of the banned

Although we’re small in numbers we’re the best banned in the land,

We’re read at wakes and weddin’s and in every parish hall,

And under library counters sure you’ll have no trouble at all.”

David Heinemann – From Dictatorship to Democracy by Gene Sharp

Running the Freedom of Expression Awards’ Fellowship and helping brave people who are often fighting totalitarian regimes can sometimes feel like an uphill battle. How can one person or organisation ever hope to defeat an entire dictatorship?

They can’t, of course, but Gene Sharp’s little book reminds me that “the deliberate, non-violent disintegration of dictatorships” is possible when people work together in certain ways. Part handbook, part political pamphlet, it’s an invaluable toolbox for any serious democratic activist. Its potency was illustrated last year when a group of young Angolans were imprisoned simply for trying to get together and discuss it at a book club.

The fact that I could read it on my commute home reminded me never to take my freedoms for granted.

Vicky Baker – The Bible

The Bible is not an obvious choice for me as I’m an atheist, but loosely picking up on that misattributed Voltaire quote, I would defend anyone’s right to read it – or indeed any other religious book.

Pope Francis has called The Bible “an extremely dangerous book”. Owning it or reading it can get you still get you imprisoned or killed in certain parts of the world. This is the sort of book banning that we should all be extremely worried about, whatever your religion.

These days I don’t even have a copy in my house, but its stories formed part of my childhood. When I grew up I learnt that my hometown, Amersham in Buckinghamshire, also had an important connection to censorship of The Bible. In the 16th century a group of local Lollards were burned at the stake for wanting to translate the book from Latin to English; some of their children were forced to light the pyre.

Known as the Amersham Martyrs, they have since been honoured in a memorial stone, costumed walking tours, and through occasional community plays about their lives, staged in a local church. (Imagine if the bishop who sentenced them saw this today.)

Sadly, we live in a world where censorship of the Bible is not ancient history. In 2014, an American man was sent to labour camp in North Korea for leaving a Bible in a restaurant’s bathroom when visiting as a tourist. It was deemed a crazy act – and, indeed, the move also endangered his local tour guides – but it is outrageous that simply leaving a book behind, so readers can choose to pick it up or not, can still lead to such punishments.

David Sewell – The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien

One of those cases in the USA where the pressure to ban comes not from the authorities, but from citizens wanting it pulled from libraries or schools. Complaints were made about its sweary language and its graphic depictions of violence and death. But there again it’s about a grunt’s eye view of the Vietnam war, so go figure.

Only this is really a remarkable work of fiction, which is highly literary in its narrative form. It uses stories to try and construct the extreme experience of war, but also uses war to explore the drive to create stories for ourselves. Language is used to defang terror on the battlefield, stories are invented (and embellished through the re-telling) to keep dead comrades alive, because if they are allowed to die, then it brings death one step closer to the surviving soldiers.

A fascinating book that tries to put words to the unsayable and unspeakable, and its would-be censors are attempting to make it a different kind of unspeakable and unsayable.

Kieran Etoria-King – Riotous Assembly by Tom Sharpe

One of the most enduring, darkly funny things I’ve ever read was the opening chapter of Tom Sharpe’s 1971 novel Riotous Assembly, in which a South African police chief argues with an old white woman who shot her black chef in the garden of her stately home. As two deputies collect up the obliterated corpse of the man she killed with a four-barrelled elephant gun, Miss Hazelstone, who graphically describes her illicit love affair with the chef, demands to be arrested for murder, while a disgusted Kommandant van Heerden insists that the killing of a black person is not murder. Meanwhile, the entire police force of the fictional town of Piemburg, operating under mistaken intelligence, are engaged in a fierce and escalating firefight at the gate, unaware that they are actually shooting at each other from behind cover.

Sharpe had lived in South Africa from 1951 to 1961 before he was deported over a play he staged that criticised the government, so he had an intimate knowledge of the country and Riotous Assembly, a hilarious send-up of the South African police force, is driven as much by real venom and contempt for the Apartheid system as it is by vulgar humour. Of course, that system wasn’t going to tolerate such mockery and the book was banned in South Africa as well as Zimbabwe.

Helen Galliano – The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

I first came across The Master and Margarita – considered to be one of the finest novels to come out of the Soviet Union – as a performance student at Goldsmiths and a lover of magical realism. I immediately fell into Bulgakov’s wild and dangerous world of talking cats, decapitations, magic shows, Satan’s midnight ball and plenty of vodka. I was hooked, reading it multiple times throughout my third year and even created a performance reimagining Margarita’s transformation into a witch.

The forward to the 1997 translation of the novel reads: “Mikhail Bulgakov worked on this luminous book throughout one of the darkest decades of the century. His last revisions were dictated to his wife a few weeks before his death in 1940 at the age of forty-nine. For him, there was never any question of publishing the novel. The mere existence of the manuscript, had it come to the knowledge of Stalin’s police, would almost certainly have led to the permanent disappearance of its author.”

Faced with persecution, Bulgakov burned the first manuscript of The Master and Margarita, only to re-write it later from memory. It was eventually published nearly three decades after his death and since then “manuscripts don’t burn”, a famous line from the book, has come to symbolise the power and determination of human creativity against oppression.

Great literature and great ideas will always survive.

What’s it like to be an author of a banned or challenged book? How can librarians support authors who find themselves in this situation? To mark Banned Books Week, Vicky Baker, deputy editor of Index on Censorship magazine, will chair an online discussion with three authors on 29 September, followed by a Q&A. It is free to join, although attendees must register in advance.

22 Jul 2016 | Americas, mobile, News, United States

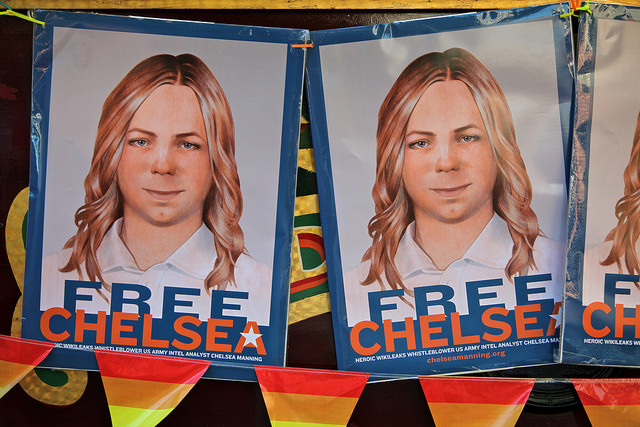

Although the USA is considered to have relatively generous freedoms of speech and the press protected under the First Amendment to the US Constitution, these freedoms have their limits. Many whistleblowers are not afforded protection in the USA and are subjected to lengthy prison terms after disclosing classified information to the public.

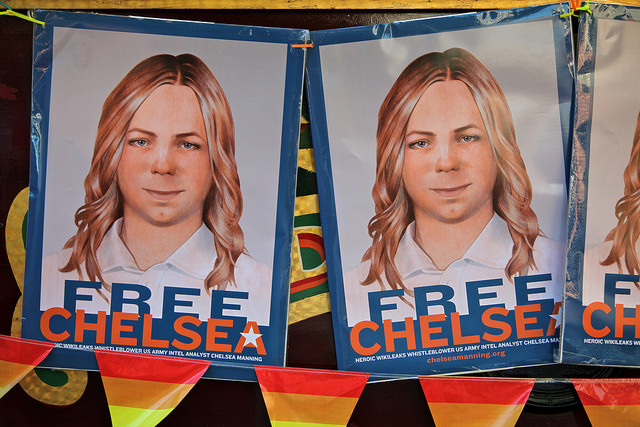

Chelsea Manning’s suicide attempt on 5 July, six years into her 35-year sentence, highlights the severity the USA practices when sentencing whistleblowers. Manning was responsible for the leaks of classified US military information to Wikileaks including videos, incident reports from the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, information on detainees at Guantanamo and thousands of Department of State cables. She was sentenced on 21 August 2013 to 35 years at the maximum-security US Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth.

Manning’s case appears to be the rule, not the exception, in the USA.

Jeffrey Sterling

Considered to be a whistleblower by some, Jeffrey Sterling, who worked for the CIA from 1993 to 2002, was charged under the Espionage Act with mishandling national defense information in 2010. Sterling was sentenced to three and a half years in prison for his contributions to New York Times journalist James Risen’s book, State of War: The Secret History of the CIA and the Bush Administration, which detailed the failed CIA Operation Merlin that may have inadvertently aided the Iranian nuclear weapons program. Risen was subpoenaed twice to testify in the case United States v Sterling but refused, resulting in a seven-year legal battle.

On 11 May 2015, at Sterling’s sentencing, judge Leonie Brinkema stated that although she was moved by his professional history, she wanted to send a message to other whistleblowers of the “price to be paid” when revealing government secrets.

Stephen Jin-Woo Kim

Stephen Kim is a former US Department of State contractor who, on 11 June 2009, spoke to Fox News reporter James Rosen about North Korean plans for a nuclear bomb test. Kim allegedly sought Rosen out after becoming frustrated that there was little being done in the Department of State in response to the threats of nuclear tests in North Korea, tests that were ultimately carried out. Fox News published Rosen’s article, North Korea Intends to Match U.N. Resolution With New Nuclear Test, which resulted in an FBI investigation. Kim subsequently pleaded guilty to a single felony count of unauthorised disclosure of national defense information and was sentenced to 13 months in prison on 7 February 2014.

John Kiriakou

John Kiriakou, a former CIA officer, was charged with disclosing information to journalists on several occasions, including revealing the use of torture on Abu Zubaydah and connecting a covert operative to a specific undercover operation. Kiriakou accepted a plea bargain that spared the journalists he had spoken with from having to testify by pleading guilty to one count of violating the Intelligence Identities Protection Act.

On 28 February 2013, Kiriakou began serving his 30-month sentence. He has stated that his case was more about punishment for exposing torture than leaking information and that he would “do it all over again”.

Edward Snowden

Although the most famous whistleblower on this list has not been tried and sentenced, Edward Snowden could face up to 30 years in prison for his multiple felony charges under the World War I-era Espionage Act. Snowden was charged on 14 June 2013 for his role in leaking classified information from the National Security Agency, notably a global surveillance initiative.

Snowden has expressed a willingness to go to prison for his actions but refuses to be used as a “deterrent to people trying to do the right thing in difficult situations” as so many whistleblowers often are.

Barrett Brown

The political climate in the US has become so hostile towards leaks that even journalists can face repercussions for their involvement with whistleblowers. American journalist and essayist Barrett Brown’s case became well-known after he was arrested for copying and pasting a hyperlink to millions of leaked emails from Stratfor, an American private intelligence company, from one chat room to another. The leak itself had been orchestrated by Jeremy Hammond, who is serving 10 years in prison for his participation, and did not involve Brown. Brown faced a sentence of up to 102 years in prison, once again for sharing a hyperlink, before the 12 counts of aggravated identity theft and trafficking in stolen data charges were dropped in 2013.

Although the dismissal of these charges was heralded as a victory for press freedom, Brown was still convicted of two counts of being an accessory after the fact and obstructing the execution of a search warrant. On 22 January 2015, Brown was sentenced to 63 months in prison and ordered to pay $890,250 in fines and restitution to Stratfor.