14 Oct 2016 | Afghanistan, Asia and Pacific, Bangladesh, Burma, India, mobile, News, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Tibet

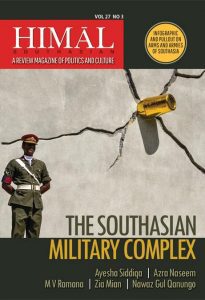

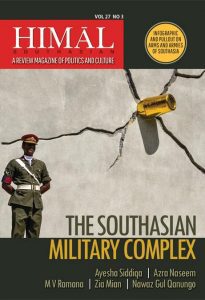

One of South Asia’s most influential news magazines, Himal Southasian, is to close next month after 29 years of publishing as part of a clampdown on freedom of expression across the region. The magazine has a specific goal: to unify the divided countries in South Asia by informing and educating readers on issues that stretch throughout the region, not just one community.

One of South Asia’s most influential news magazines, Himal Southasian, is to close next month after 29 years of publishing as part of a clampdown on freedom of expression across the region. The magazine has a specific goal: to unify the divided countries in South Asia by informing and educating readers on issues that stretch throughout the region, not just one community.

Index got a chance to speak with Himal Southasian’s editor, Aunohita Mojumdar, on the vital role of independent media in South Asia, the Nepali government’s complicated way of silencing activists and what the future holds for journalism in the region.

“The means used to silence us are not straightforward but nor are they unique,” Mojumdar said. “Throughout the region one sees increasing use of regulatory means to clamp down on freedom of expression, whether it relates to civil society activists, media houses, journalists or human rights campaigners.”

Himal Southasian, which claims to be the only analytical and regional news magazine for South Asia, faced months of bureaucratic roadblocks before the funding for the magazine’s publisher, the Southasia Trust, was cut off due to non-cooperation by regulatory state agencies in Nepal, said the editor. This is a common tactic among the neighbouring countries as governments are wary of using “direct attacks or outright censorship” for fear of public backlash.

But for Nepal it wasn’t always this way. “Nepal earlier stood as the country where independent media and civil society not accepted by their own countries could function fearlessly,” Mojumdar said.

In a statement announcing its suspension of publication as of November 2016, Himal Southasian explained that without warning, grants were cut off, work permits for editorial staff became difficult to obtain and it started to experience “unreasonable delays” when processing payments for international contributors. “We persevered through the repercussions of the political attack on Himal in Parliament in April 2014, as well as the escalating targeting of Kanak Mani Dixit, Himal’s founding editor and Trust chairman over the past year,” it added.

Index on Censorship: Why is an independent media outlet like Himal Southasian essential in South Asia?

Aunohita Mojumdar: While the region has robust media, much of it is confined in its coverage to the boundaries of the nation-states or takes a nationalistic approach while reporting on cross-border issues. Himal’s coverage is based on the understanding that the enmeshed lives of almost a quarter of the world’s population makes it imperative to deal with both challenges and opportunities in a collaborative manner.

The drum-beating jingoism currently on exhibit in the mainstream media of India and Pakistan underline how urgent it is for a different form of journalism that is fact-based and underpinned by rigorous research. Himal’s reportage and analysis generate awareness about issues and areas that are underreported. It’s long-form narrative journalism also attempts to ensure that the power of good writing generates interest in these issues. Based on a recognition of the need for social justice for the people rather than temporary pyrrhic victories for the political leaderships, Himal Southasian brings journalism back to its creed of being a public service good.

Index: Did the arrest of Kanak Mani Dixit, the founding editor for Himal Southasian, contribute to the suspension of Himal Southasian or the treatment the magazine received from regulatory agencies?

Mojumdar: In the case of Himal or its publisher the non-profit Southasia Trust, neither entity is even under investigation. We can only surmise that the tenuous link is that the chairman of the trust, Kanak Mani Dixit, is under investigation since we have received no formal information. Informally we have indeed been told that there is political pressure related to the “investigation” which prevents the regulatory bodies from providing their approval.

The lengthy process of this denial – we had applied in January 2016 for the permission to use a secured grant and in December 2015 for the work permit, effectively diminished our ability to function as an organisation until the point of paralysis. While the case against Dixit is itself contentious and currently sub judice, Himal has not been intimated by any authority that it is under any kind of scrutiny. On the contrary, regulatory officials inform us informally that we have fulfilled every requirement of law and procedure, but cite political pressure for their inability to process our requests. Our finances are audited independently and the audit report, financial statements, bank statements and financial reporting are submitted to the Nepal government’s regulatory bodies as well as to the donors.

Index: Why is Nepal utilising bureaucracy to indirectly shut down independent media? Why are they choosing indirect methods rather than direct censorship?

Mojumdar: The means used to silence us are not straightforward but nor are they unique. Throughout the region one sees increasing use of regulatory means to clamp down on freedom of expression, whether it relates to civil society activists, media houses, journalists or human rights campaigners. Direct attacks or outright censorship are becoming rarer as governments have begun to fear the backlash of public protests.

Index: With the use of bureaucratic force to shut down civil society activists and media growing in Nepal, how does the future look for independent media in South Asia?

Mojumdar: This is actually a regional trend. However, while Nepal earlier stood as the country where independent media and civil society not accepted by their own countries could function fearlessly, the closing down of this space in Nepal is a great loss. As a journalist I myself was supported by the existence of the Himal Southasian platform. When the media of my home country, India, were not interested in publishing independent reporting from Afghanistan, Himal reached out to me and published my article for the eight years that I was based in Kabul as a freelancer. We are constantly approached by journalists wishing to write the articles that they cannot publish in their own national media.

The fact that regulatory means to silence media and civil society is meeting with such success here and that an independent platform is getting scarce support within Nepal’s civil society will also be a signal for others in power wishing to use the same means against voices of dissent.

It is a struggle for the media to be independent and survive. In an era where corporate interests increasingly drive the media’s agenda, it is important for all of us to reflect on what we can all do to ensure the survival of small independent organisations, many of which, like us, face severe challenges.

19 Sep 2016 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, mobile, Volume 45.03 Autumn 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Does anonymity need to be defended? Contributors include Hilary Mantel, Can Dündar, Valerie Plame Wilson, Julian Baggini, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Maria Stepanova “][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2”][vc_column_text]

The latest issue of Index on Censorship explores anonymity through a range of in-depth features, interviews and illustrations from around the world. The special report looks at the pros and cons of masking identities from the perspective of a variety of players, from online trolls to intelligence agencies, whistleblowers, activists, artists, journalists, bloggers and fixers.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”78078″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Former CIA agent Valerie Plame Wilson writes on the damage done when her cover was blown, journalist John Lloyd looks at how terrorist attacks have affected surveillance needs worldwide, Bangladeshi blogger Ananya Azad explains why he was forced into exile after violent attacks on secular writers, philosopher Julian Baggini looks at the power of literary aliases through the ages, Edward Lucas shares The Economist’s perspective on keeping its writers unnamed, John Crace imagines a meeting at Trolls Anonymous, and Caroline Lees looks at how local journalists, or fixers, can be endangered, or even killed, when they are revealed to be working with foreign news companies. There are are also features on how Turkish artists moonlight under pseudonyms to stay safe, how Chinese artists are being forced to exhibit their works in secret, and an interview with Los Angeles street artist Skid Robot.

Outside of the themed report, this issue also has a thoughtful essay by novelist Hilary Mantel, called Blot, Erase, Delete, about the importance of committing to your words, whether you’re a student, an author, or a politician campaigner in the Brexit referendum. Andrey Arkhangelsky looks back at the last 10 years of Russian journalism, in the decade after the murder of investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya. Uzbek writer Hamid Ismailov looks at how metaphor has taken over post-Soviet literature and prevented it tackling reality head-on. Plus there is poetry from Chilean-French director Alejandro Jodorowsky and Russian writer Maria Stepanova, plus new fiction from Turkey and Egypt, via Kaya Genç and Basma Abdel Aziz.

There is art work from Molly Crabapple, Martin Rowson, Ben Jennings, Rebel Pepper, Eva Bee, Brian John Spencer and Sam Darlow.

You can order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: THE UNNAMED” css=”.vc_custom_1483445324823{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Does anonymity need to be defended?

Anonymity: worth defending, by Rachael Jolley: False names can be used by the unscrupulous but the right to anonymity needs to be defended

Under the wires, by Caroline Lees : A look at local “fixers”, who help foreign correspondents on the ground, can face death threats and accusations of being spies after working for international media

Art attack, by Jemimah Steinfeld: Ai Weiwei and other artists have increased the popularity of Chinese art, but censorship has followed

Naming names, by Suhrith Parthasarathy: India has promised to crack down on online trolls, but the right to anonymity is also threatened

Secrets and spies, by Valerie Plame Wilson: The former CIA officer on why intelligence agents need to operate undercover, and on the damage done when her cover was blown in a Bush administration scandal

Undercover artist, by Jan Fox: Los Angeles street artist Skid Robot explains why his down-and-out murals never carry his real name

A meeting at Trolls Anonymous, by John Crace: A humorous sketch imagining what would happen if vicious online commentators met face to face

Whose name is on the frame? By Kaya Genç: Why artists in Turkey have adopted alter egos to hide their more political and provocative works

Spooks and sceptics, by John Lloyd: After a series of worldwide terrorist attacks, the public must decide what surveillance it is willing to accept

Privacy and encryption, by Bethany Horne: An interview with human rights researcher Jennifer Schulte on how she protects herself in the field

“I have a name”, by Ananya Azad: A Bangladeshi blogger speaks out on why he made his identity known and how this put his life in danger

The smear factor, by Rupert Myers: The power of anonymous allegations to affect democracy, justice and the political system

Stripsearch cartoon, by Martin Rowson: When a whistleblower gets caught …

Signing off, by Julian Baggini: From Kierkegaard to JK Rowling, a look at the history of literary pen names and their impact

The Snowden effect, by Charlie Smith: Three years after Edward Snowden’s mass-surveillance leaks, does the public care how they are watched?

Leave no trace, by Mark Frary: Five ways to increase your privacy when browsing online

Goodbye to the byline, by Edward Lucas: A senior editor at The Economist explains why the publication does not name its writers in print

What’s your emergency? By Jason DaPonte: How online threats can lead to armed police at your door

Yakety yak (don’t hate back), by Sean Vannata: How a social network promising anonymity for users backtracked after being banned on US campuses

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Blot, erase, delete, by Hilary Mantel: How the author found her voice and why all writers should resist the urge to change their past words

Murder in Moscow: Anna’s legacy, by Andrey Arkhangelsky: Ten years after investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya was killed, where is Russian journalism today?

Writing in riddles, by Hamid Ismailov: Too much metaphor has restricted post-Soviet literature

Owners of our own words, by Irene Caselli: Aftermath of a brutal attack on an Argentinian newspaper

Sackings, South Africa and silence, by Natasha Joseph: What is the future for public broadcasting in southern Africa after the sackings of SABC reporters?

“Journalists must not feel alone”, by Can Dündar: An exiled Turkish editor on the need to collaborate internationally so investigations can cross borders

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Bottled-up messages, by Basma Abdel Aziz: A short story from Egypt about a woman feeling trapped. Interview with the author by Charlotte Bailey

Muscovite memories, by Maria Stepanova: A poem inspired by the last decade in Putin’s Russia

Silence is not golden, by Alejandro Jodorowsky: An exclusive translation of the Chilean-French film director’s poem What One Must Not Silence

Write man for the job, by Kaya Genç: A new short story about a failed writer who gets a job policing the words of dissidents in Turkey

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view, by Jodie Ginsberg: Europe’s right-to-be-forgotten law pushed to new extremes after a Belgian court rules that individuals can force newspapers to edit archive articles

Index around the world, by

Josie Timms: Rounding up Index’s recent work, from a hip-hop conference to the latest from Mapping Media Freedom

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

What ever happened to Luther Blissett? By Vicky Baker: How Italian activists took the name of an unsuspecting English footballer, and still use it today

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483444808560-b79f752f-ec25-7″ taxonomies=”8927″ exclude=”80882″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483444808560-b79f752f-ec25-7″ taxonomies=”8927″ exclude=”80882″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Aug 2016 | Bangladesh, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

Shafik Rehman (Photo: Reprieve)

Anisul Huq

Minister for Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs

Government of Bangladesh

Bangladesh Secretariat, Building No. 4 (7th Floor) Dhaka-100

4 August 2016

Dear Mr Huq,

We are writing to you as international press freedom, freedom of expression and media advocacy groups about the ongoing detention of Shafik Rehman, an elderly journalist in custody in Dhaka, to set out several serious concerns about his treatment.

We were pleased to note that on Sunday 17 July 2016 the Supreme Court granted Mr Rehman’s request for leave to appeal his detention.

Detention without charge

Mr Rehman was arrested on 16 April 2016 and denied bail by the High Court on 7 June 2016. After more than three months in detention, he has still not been charged with any crime.

He is being investigated by the Bangladesh Detective Branch, who entered his house without a warrant, inexplicably posing as a camera crew, on the day of his arrest.

The detectives missed a deadline on 16 June 2016 to submit a report to Metropolitan Magistrate SM Masud Zaman in Dhaka outlining the alleged case against Mr Rehman. The court extended the deadline until 26 July 2016, despite the fact that the First Information Report in this case was initially filed in August 2015 and the investigation period in the case has expired. On 26 July 2016, the police once again missed the deadline to submit their investigation report and a further deadline has now been set for 30 August 2016 – more than 100 days after his arrest.

Under international law, the Bangladesh authorities have a duty to promptly inform Mr Rehman of the nature of the case against him and either charge or release him. The delays in this case suggest that there is no evidence against Mr Rehman, and that he should be released.

Journalistic career

Mr Rehman is a professional journalist who has spent a lifetime working for freedom of expression. We are concerned that his arrest represents an attack on press freedoms and forms part of a worrying trend in Bangladesh. At the time of his arrest, Mr Rehman was editor of the popular monthly magazine Mouchake Dhil, with experience as a TV host and producer. Previously, he has worked for the BBC and edited Jai Jai Din, a mass- circulation Bengali daily.

The arrest of journalists like Mr Rehman raises concerns about the state of press freedoms in Bangladesh, where several prominent editors have been arrested in recent years.

Denied bail

Mr Rehman is an elderly man in poor health. He spent the first weeks of detention in solitary confinement, without a bed. His health deteriorated and he was rushed to hospital.

His family are seriously concerned about his health failing in prison, and he has missed important medical appointments while on remand.

There are therefore strong compassionate grounds for releasing Mr Rehman on bail, while any evidence (if there is any at all) can be gathered without jeopardising his health.

We hope that Mr Rehman’s appeal will be an opportunity for the Court to take stock of the serious concerns about the case against Mr Rehman and about his health and well-being while he remains in custody.

We appreciate you hearing our concerns and are grateful for swift action to guarantee Mr Rehman’s prompt release.

Yours sincerely,

Reprieve | Index on Censorship | International Federation of Journalists | Reporters Without Borders | Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech | Afghanistan Journalists Center | Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain | Bahrain Center for Human Rights | Canadian Journalists for Free Expression | Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility | Foro de Periodismo Argentino | Free Media Movement | Independent Journalism Center – Moldova | Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information | International Press Institute | Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance | Media Foundation for West Africa | National Union of Somali Journalists | Norwegian PEN | Pacific Freedom Forum | Pacific Islands News Association | Pakistan Press Foundation | Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedoms – MADA | PEN American Center | Public Association “Journalists” | Vigilance pour la Démocratie et l’État Civique

Via post to:

High Commission for the People’s Republic of Bangladesh

28 Queen’s Gate

London

SW7 5JA

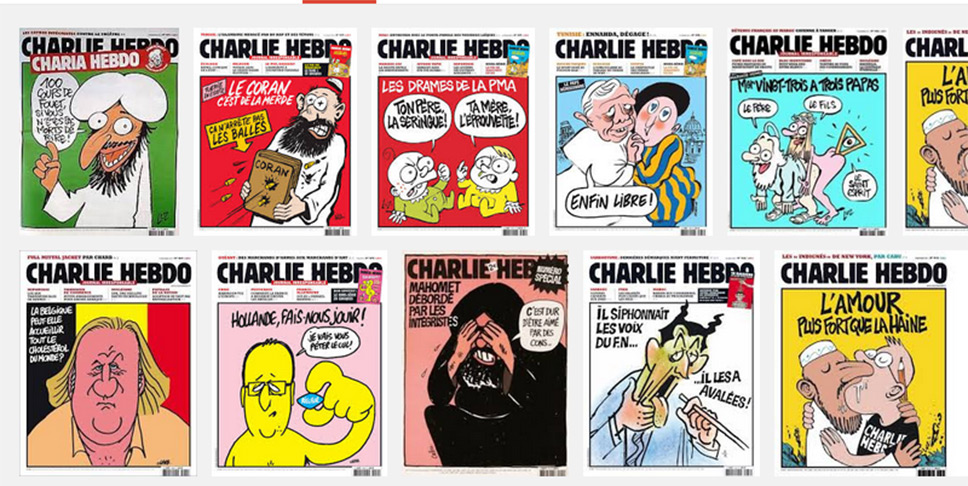

7 Jan 2016 | France, Mapping Media Freedom, News, Statements, United Kingdom

When I started working at Index on Censorship, some friends (including some journalists) asked why an organisation defending free expression was needed in the 21st century. “We’ve won the battle,” was a phrase I heard often. “We have free speech.”

There was another group who recognised that there are many places in the world where speech is curbed (North Korea was mentioned a lot), but most refused to accept that any threat existed in modern, liberal democracies.

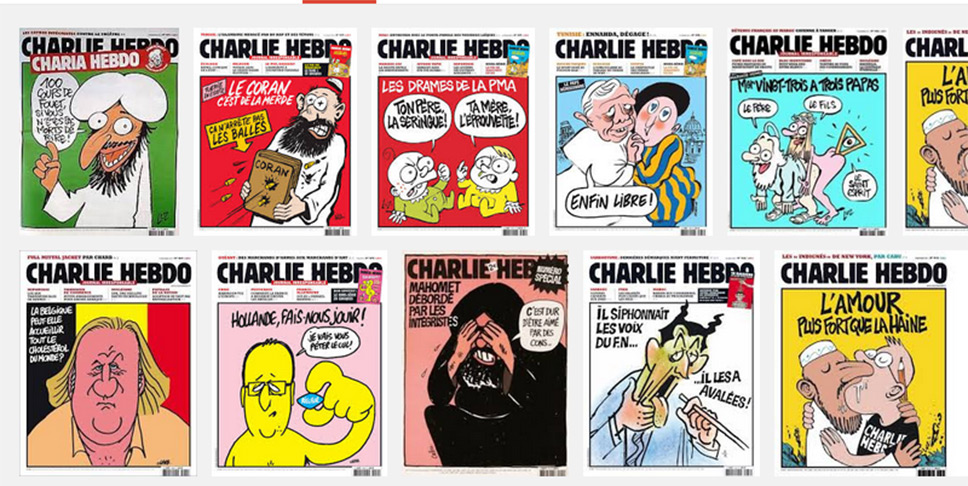

After the killing of 12 people at the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, that argument died away. The threats that Index sees every day – in Bangladesh, in Iran, in Mexico, the threats to poets, playwrights, singers, journalists and artists – had come to Paris. And so, by extension, to all of us.

Those to whom I had struggled to explain the creeping forms of censorship that are increasingly restraining our freedom to express ourselves – a freedom which for me forms the bedrock of all other liberties and which is essential for a tolerant, progressive society – found their voice. Suddenly, everyone was “Charlie”, declaring their support for a value whose worth they had, in the preceding months, seemingly barely understood, and certainly saw no reason to defend.

The heartfelt response to the brutal murders at Charlie Hebdo was strong and felt like it came from a united voice. If one good thing could come out of such killings, I thought, it would be that people would start to take more seriously what it means to believe that everyone should have the right to speak freely. Perhaps more attention would fall on those whose speech is being curbed on a daily basis elsewhere in the world: the murders of atheist bloggers in Bangladesh, the detention of journalists in Azerbaijan, the crackdown on media in Turkey. Perhaps this new-found interest in free expression – and its value – would also help to reignite debate in the UK, France and other democracies about the growing curbs on free speech: the banning of speakers on university campuses, the laws being drafted that are meant to stop terrorism but which can catch anyone with whom the government disagrees, the individuals jailed for making jokes.

And, in a way, this did happen. At least, free expression was “in vogue” for much of 2015. University debating societies wanted to discuss its limits, plays were written about censorship and the arts, funds raised to keep Charlie Hebdo going in defiance against those who would use the “assassin’s veto” to stop them. It was also a tense year. Events discussing hate speech or cartooning for which six months previously we might have struggled to get an audience were now being held to full houses. But they were also marked by the presence of police, security guards and patrol cars. I attended one seminar at which a participant was accompanied at all times by two bodyguards. Newspapers and magazines across London conducted security reviews.

But after the dust settled, after the initial rush of apparent solidarity, it became clear that very few people were actually for free speech in the way we understand it at Index. The “buts” crept quickly in – no one would condone violence to deal with troublesome speech, but many were ready to defend a raft of curbs on speech deemed to be offensive, or found they could only defend certain kinds of speech. The PEN American Center, which defends the freedom to write and read, discovered this in May when it awarded Charlie Hebdo a courage award and a number of novelists withdrew from the gala ceremony. Many said they felt uncomfortable giving an award to a publication that drew crude caricatures and mocked religion.

Index’s project Mapping Media Freedom recorded 745 violations against media freedom across Europe in 2015.

The problem with the reaction of the PEN novelists is that it sends the same message as that used by the violent fundamentalists: that only some kinds of speech are worth defending. But if free speech is to mean anything at all, then we must extend the same privileges to speech we dislike as to that of which we approve. We cannot qualify this freedom with caveats about the quality of the art, or the acceptability of the views. Because once you start down that route, all speech is fair game for censorship – including your own.

As Neil Gaiman, the writer who stepped in to host one of the tables at the ceremony after others pulled out, once said: “…if you don’t stand up for the stuff you don’t like, when they come for the stuff you do like, you’ve already lost.”

Index believes that speech and expression should be curbed only when it incites violence. Defending this position is not easy. It means you find yourself having to defend the speech rights of religious bigots, racists, misogynists and a whole panoply of people with unpalatable views. But if we don’t do that, why should the rights of those who speak out against such people be defended?

In 2016, if we are to defend free expression we need to do a few things. Firstly, we need to stop banning stuff. Sometimes when I look around at the barrage of calls for various people to be silenced (Donald Trump, Germaine Greer, Maryam Namazie) I feel like I’m in that scene from the film Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels where a bunch of gangsters keep firing at each other by accident and one finally shouts: “Could everyone stop getting shot?” Instead of demanding that people be prevented from speaking on campus, debate them, argue back, expose the holes in their rhetoric and the flaws in their logic.

Secondly, we need to give people the tools for that fight. If you believe as I do that the free flow of ideas and opinions – as opposed to banning things – is ultimately what builds a more tolerant society, then everyone needs to be able to express themselves. One of the arguments used often in the wake of Charlie Hebdo to potentially excuse, or at least explain, what the gunmen did is that the Muslim community in France lacks a voice in mainstream media. Into this vacuum, poisonous and misrepresentative ideas that perpetuate stereotypes and exacerbate hatreds can flourish. The person with the microphone, the pen or the printing press has power over those without.

It is important not to dismiss these arguments but it is vital that the response is not to censor the speaker, the writer or the publisher. Ideas are not challenged by hiding them away and minds not changed by silence. Efforts that encourage diversity in media coverage, representation and decision-making are a good place to start.

Finally, as the reaction to the killings in Paris in November showed, solidarity makes a difference: we need to stand up to the bullies together. When Index called for republication of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons shortly after the attacks, we wanted to show that publishers and free expression groups were united not by a political philosophy, but by an unwillingness to be cowed by bullies. Fear isolates the brave – and it makes the courageous targets for attack. We saw this clearly in the days after Charlie Hebdo when British newspapers and broadcasters shied away from publishing any of the cartoons featuring the Prophet Mohammed. We need to act together in speaking out against those who would use violence to silence us.

As we see this week, threats against freedom of expression in Europe come in all shapes and sizes. The Polish government’s plans to appoint the heads of public broadcasters has drawn complaints to the Council of Europe from journalism bodies, including Index, who argue that the changes would be “wholly unacceptable in a genuine democracy”.

In the UK, plans are afoot to curb speech in the name of protecting us from terror but which are likely to have far-reaching repercussions for all. Index, along with colleagues at English PEN, the National Secular Society and the Christian Institute will be working to ensure that doesn’t happen. This year, as every year, defending free speech will begin at home.

One of South Asia’s most influential news magazines, Himal Southasian, is to close next month after 29 years of publishing as part of a clampdown on freedom of expression across the region. The magazine has a specific goal: to unify the divided countries in South Asia by informing and educating readers on issues that stretch throughout the region, not just one community.

One of South Asia’s most influential news magazines, Himal Southasian, is to close next month after 29 years of publishing as part of a clampdown on freedom of expression across the region. The magazine has a specific goal: to unify the divided countries in South Asia by informing and educating readers on issues that stretch throughout the region, not just one community.