Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Saudi journalist, Global Opinions columnist for the Washington Post, and former editor-in-chief of Al-Arab News Channel Jamal Khashoggi offers remarks during POMED’s “Mohammed bin Salman’s Saudi Arabia: A Deeper Look”. March 21, 2018, Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED), Washington, DC.

Recognising the fundamental right to express our views, free from repression, we the undersigned civil society organisations call on the international community, including the United Nations, multilateral and regional institutions as well as democratic governments committed to the freedom of expression, to take immediate steps to hold Saudi Arabia accountable for grave human rights violations. The murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi in the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul on 2 October is only one of many gross and systematic violations committed by the Saudi authorities inside and outside the country. As the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists approaches on 2 November, we strongly echo calls for an independent investigation into Khashoggi’s murder, in order to hold those responsible to account.

This case, coupled with the rampant arrests of human rights defenders, including journalists, scholars and women’s rights activists; internal repression; the potential imposition of the death penalty on demonstrators; and the findings of the UN Group of Eminent Experts report which concluded that the Coalition, led by Saudi Arabia, have committed acts that may amount to international crimes in Yemen, all demonstrate Saudi Arabia’s record of gross and systematic human rights violations. Therefore, our organisations further urge the UN General Assembly to suspend Saudi Arabia from the UN Human Rights Council (HRC), in accordance with operative paragraph 8 of the General Assembly resolution 60/251.

Saudi Arabia has never had a reputation for tolerance and respect for human rights, but there were hopes that as Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman rolled out his economic plan (Vision 2030), and finally allowed women to drive, there would be a loosening of restrictions on women’s rights, and freedom of expression and assembly. However, prior to the driving ban being lifted in June, women human rights defenders received phone calls warning them to remain silent. The Saudi authorities then arrested dozens of women’s rights defenders (both female and male) who had been campaigning against the driving ban. The Saudi authorities’ crackdown against all forms of dissent has continued to this day.

Khashoggi criticised the arrests of human rights defenders and the reform plans of the Crown Prince, and was living in self-imposed exile in the US. On 2 October 2018, Khashoggi went to the Consulate in Istanbul with his fiancée to complete some paperwork, but never came out. Turkish officials soon claimed there was evidence that he was murdered in the Consulate, but Saudi officials did not admit he had been murdered until more than two weeks later.

It was not until two days later, on 20 October, that the Saudi public prosecution’s investigation released findings confirming that Khashoggi was deceased. Their reports suggested that he died after a “fist fight” in the Consulate, and that 18 Saudi nationals have been detained. King Salman also issued royal decrees terminating the jobs of high-level officials, including Saud Al-Qahtani, an advisor to the royal court, and Ahmed Assiri, deputy head of the General Intelligence Presidency. The public prosecution continues its investigation, but the body has not been found.

Given the contradictory reports from Saudi authorities, it is essential that an independent international investigation is undertaken.

On 18 October, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and Reporters Without Borders (RSF) called on Turkey to request that UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres establish a UN investigation into the extrajudicial execution of Khashoggi.

On 15 October 2018, David Kaye, the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression, and Dr. Agnès Callamard, the UN Special Rapporteur on summary executions, called for “an independent investigation that could produce credible findings and provide the basis for clear punitive actions, including the possible expulsion of diplomatic personnel, removal from UN bodies (such as the Human Rights Council), travel bans, economic consequences, reparations and the possibility of trials in third states.”

We note that on 27 September, Saudi Arabia joined consensus at the UN HRC as it adopted a new resolution on the safety of journalists (A/HRC/Res/39/6). We note the calls in this resolution for “impartial, thorough, independent and effective investigations into all alleged violence, threats and attacks against journalists and media workers falling within their jurisdiction, to bring perpetrators, including those who command, conspire to commit, aid and abet or cover up such crimes to justice.” It also “[u]rges the immediate and unconditional release of journalists and media workers who have been arbitrarily arrested or arbitrarily detained.”

Khashoggi had contributed to the Washington Post and Al-Watan newspaper, and was editor-in-chief of the short-lived Al-Arab News Channel in 2015. He left Saudi Arabia in 2017 as arrests of journalists, writers, human rights defenders and activists began to escalate. In his last column published in the Washington Post, he criticised the sentencing of journalist Saleh Al-Shehi to five years in prison in February 2018. Al-Shehi is one of more than 15 journalists and bloggers who have been arrested in Saudi Arabia since September 2017, bringing the total of those in prison to 29, according to RSF, while up to 100 human rights defenders and possibly thousands of activists are also in detention according to the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR) and Saudi partners including ALQST. Many of those detained in the past year had publicly criticised reform plans related to Vision 2030, noting that women would not achieve economic equality merely by driving.

Another recent target of the crackdown on dissent is prominent economist Essam Al-Zamel, an entrepreneur known for his writing about the need for economic reform. On 1 October 2018, the Specialised Criminal Court (SCC) held a secret session during which the Public Prosecution charged Al-Zamel with violating the Anti Cyber Crime Law by “mobilising his followers on social media.” Al-Zamel criticised Vision 2030 on social media, where he had one million followers. Al-Zamel was arrested on 12 September 2017 at the same time as many other rights defenders and reformists.

The current unprecedented targeting of women human rights defenders started in January 2018 with the arrest of Noha Al-Balawi due to her online activism in support of social media campaigns for women’s rights such as (#Right2Drive) or against the male guardianship system (#IAmMyOwnGuardian). Even before that, on 10 November 2017, the SCC in Riyadh sentenced Naimah Al-Matrod to six years in jail for her online activism.

The wave of arrests continued after the March session of the HRC and the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) published its recommendations on Saudi Arabia. Loujain Al-Hathloul, was abducted in the Emirates and brought to Saudi Arabia against her will on 15 May 2018; followed by the arrest of Dr. Eman Al-Nafjan, founder and author of the Saudiwoman’s Weblog, who had previously protested the driving ban; and Aziza Al-Yousef, a prominent campaigner for women’s rights.

Four other women’s human rights defenders who were arrested in May 2018 include Dr. Aisha Al-Manae, Dr. Hessa Al-Sheikh and Dr. Madeha Al-Ajroush, who took part in the first women’s protest movement demanding the right to drive in 1990; and Walaa Al-Shubbar, a young activist well-known for her campaigning against the male guardianship system. They are all academics and professionals who supported women’s rights and provided assistance to survivors of gender-based violence. While they have since been released, all four women are believed to be still facing charges.

On 6 June 2018, journalist, editor, TV producer and woman human rights defender Nouf Abdulaziz was arrested after a raid on her home. Following her arrest, Mayya Al-Zahrani published a letter from Abdulaziz, and was then arrested herself on 9 June 2018, for publishing the letter.

On 27 June 2018, Hatoon Al-Fassi, a renowned scholar, and associate professor of women’s history at King Saud University, was arrested. She has long been advocating for the right of women to participate in municipal elections and to drive, and was one of the first women to drive the day the ban was lifted on 24 June 2018.

Twice in June, UN special procedures called for the release of women’s rights defenders. On 27 June 2018, nine independent UN experts stated, “In stark contrast with this celebrated moment of liberation for Saudi women, women’s human rights defenders have been arrested and detained on a wide scale across the country, which is truly worrying and perhaps a better indication of the Government’s approach to women’s human rights.” They emphasised that women human rights defenders “face compounded stigma, not only because of their work as human rights defenders, but also because of discrimination on gender grounds.”

Nevertheless, the arrests of women human rights defenders continued with Samar Badawi and Nassima Al-Sadah on 30 July 2018. They are being held in solitary confinement in a prison that is controlled by the Presidency of State Security, an apparatus established by order of King Salman on 20 July 2017. Badawi’s brother Raif Badawi is currently serving a 10-year prison sentence for his online advocacy, and her former husband Waleed Abu Al-Khair, is serving a 15-year sentence. Abu Al-Khair, Abdullah Al-Hamid, and Mohammad Fahad Al-Qahtani (the latter two are founding members of the Saudi Civil and Political Rights Association – ACPRA) were jointly awarded the Right Livelihood Award in September 2018. Yet all of them remain behind bars.

Relatives of other human rights defenders have also been arrested. Amal Al-Harbi, the wife of prominent activist Fowzan Al-Harbi, was arrested by State Security on 30 July 2018 while on the seaside with her children in Jeddah. Her husband is another jailed member of ACPRA. Alarmingly, in October 2018, travel bans were imposed against the families of several women’s rights defenders, such as Aziza Al-Yousef, Loujain Al-Hathloul and Eman Al-Nafjan.

In another alarming development, at a trial before the SCC on 6 August 2018, the Public Prosecutor called for the death penalty for Israa Al-Ghomgam who was arrested with her husband Mousa Al-Hashim on 6 December 2015 after they participated in peaceful protests in Al-Qatif. Al-Ghomgam was charged under Article 6 of the Cybercrime Act of 2007 in connection with social media activity, as well as other charges related to the protests. If sentenced to death, she would be the first woman facing the death penalty on charges related to her activism. The next hearing is scheduled for 28 October 2018.

The SCC, which was set up to try terrorism cases in 2008, has mostly been used to prosecute human rights defenders and critics of the government in order to keep a tight rein on civil society.

On 12 October 2018, UN experts again called for the release of all detained women human rights defenders in Saudi Arabia. They expressed particular concern about Al-Ghomgam’s trial before the SCC, saying, “Measures aimed at countering terrorism should never be used to suppress or curtail human rights work.” It is clear that the Saudi authorities have not acted on the concerns raised by the special procedures – this non-cooperation further brings their membership on the HRC into disrepute.

Many of the human rights defenders arrested this year have been held in incommunicado detention with no access to families or lawyers. Some of them have been labelled traitors and subjected to smear campaigns in the state media, escalating the possibility they will be sentenced to lengthy prison terms. Rather than guaranteeing a safe and enabling environment for human rights defenders at a time of planned economic reform, the Saudi authorities have chosen to escalate their repression against any dissenting voices.

Our organisations reiterate our calls to the international community to hold Saudi Arabia accountable and not allow impunity for human rights violations to prevail.

We call on the international community, and in particular the UN, to:

We call on the authorities in Saudi Arabia to:

Signed,

Access Now

Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture (ACAT) – France

Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture (ACAT) – Germany

Al-Marsad – Syria

ALQST for Human Rights

ALTSEAN-Burma

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

Amman Center for Human Rights Studies (ACHRS) – Jordan

Amman Forum for Human Rights

Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI)

Armanshahr/OPEN ASIA

ARTICLE 19

Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA)

Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC)

Asociación Libre de Abogadas y Abogados (ALA)

Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression (AFTE)

Association for Human Rights in Ethiopia (AHRE)

Association malienne des droits de l’Homme (AMDH)

Association mauritanienne des droits de l’Homme (AMDH)

Association nigérienne pour la défense des droits de l’Homme (ANDDH)

Association of Tunisian Women for Research on Development

Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID)

Awan Awareness and Capacity Development Organization

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Bureau for Human Rights and the Rule of Law – Tajikistan

Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS)

Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (LICADHO)

Canadian Center for International Justice

Caucasus Civil Initiatives Center (CCIC)

Center for Civil Liberties – Ukraine

Center for Prisoners’ Rights

Center for the Protection of Human Rights “Kylym Shamy” – Kazakhstan

Centre oecuménique des droits de l’Homme (CEDH) – Haïti

Centro de Políticas Públicas y Derechos Humanos (EQUIDAD) – Perú

Centro para la Acción Legal en Derechos Humanos (CALDH) – Guatemala

Citizen Center for Press Freedom

Citizens’ Watch – Russia

CIVICUS

Civil Society Institute (CSI) – Armenia

Code Pink

Columbia Law School Human Rights Clinic

Comité de acción jurídica (CAJ) – Argentina

Comisión Ecuménica de Derechos Humanos (CEDHU) – Ecuador

Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos – Dominican Republic

Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) -Northern Ireland

Committee to Protect Journalists

Committee for Respect of Liberties and Human Rights in Tunisia

Damascus Center for Human Rights in Syria

Danish PEN

DITSHWANELO – The Botswana Center for Human Rights

Dutch League for Human Rights (LvRM)

Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Center – Azerbaijan

English PEN

European Centre for Democracy and Human Rights (ECDHR)

European Saudi Organisation for Human Rights (ESOHR)

FIDH within the framework of the Observatory for the protection of human rights defenders

Finnish League for Human Rights

Freedom Now

Front Line Defenders

Fundación regional de asesoría en derechos humanos (INREDH) – Ecuador

Foundation for Human Rights Initiative (FHRI) – Uganda

Global Voices Advox

Groupe LOTUS (RDC)

Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR)

Hellenic League for Human Rights (HLHR)

Human Rights Association (IHD) – Turkey

Human Rights Center (HRCIDC) – Georgia

Human Rights Center “Viasna” – Belarus

Human Rights Commission of Pakistan

Human Rights Concern (HRCE) – Eritrea

Human Rights in China

Human Rights Center Memorial

Human Rights Movement “Bir Duino Kyrgyzstan”

Human Rights Sentinel

IFEX

Index on Censorship

Initiative for Freedom of Expression (IFoX) – Turkey

Institut Alternatives et Initiatives citoyennes pour la Gouvernance démocratique (I-AICGD) – DR Congo

International Center for Supporting Rights and Freedoms (ICSRF) – Switzerland

Internationale Liga für Menscherechte

International Human Rights Organisation “Fiery Hearts Club” – Uzbekistan

International Legal Initiative (ILI) – Kazakhstan

International Media Support (IMS)

International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR)

International Press Institute

International Service for Human Rights (ISHR)

Internet Law Reform and Dialogue (iLaw)

Iraqi Association for the Defense of Journalists’ Rights

Iraqi Hope Association

Italian Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

Justice for Iran

Karapatan – Philippines

Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and the Rule of Law

Khiam Rehabilitation Center for Victims of Torture

KontraS

Latvian Human Rights Committee

Lao Movement for Human Rights

Lawyers’ Rights Watch Canada

League for the Defense of Human Rights in Iran (LDDHI)

Legal Clinic “Adilet” – Kyrgyzstan

Ligue algérienne de défense des droits de l’Homme (LADDH)

Ligue centrafricaine des droits de l’Homme

Ligue des droits de l’Homme (LDH) Belgium

Ligue des Electeurs (LE) – DRC

Ligue ivoirienne des droits de l’Homme (LIDHO)

Ligue sénégalaise des droits humains (LSDH)

Ligue tchadienne des droits de l’Homme (LTDH)

Maison des droits de l’Homme (MDHC) – Cameroon

Maharat Foundation

MARUAH – Singapore

Middle East and North Africa Media Monitoring Observatory

Monitoring Committee on Attacks on Lawyers, International Association of People’s Lawyers (IAPL)

Movimento Nacional de Direitos Humanos (MNDH) – Brasil

Muslims for Progressive Values

Mwatana Organization for Human Rights

National Syndicate of Tunisian Journalists

No Peace Without Justice

Norwegian PEN

Odhikar

Open Azerbaijan Initiative

Organisation marocaine des droits humains (OMDH)

People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy (PSPD)

People’s Watch

PEN America

PEN Canada

PEN International

PEN Lebanon

PEN Québec

Promo-LEX – Moldova

Public Foundation – Human Rights Center “Kylym Shamy” – Kyrgyzstan

Rafto Foundation for Human Rights

RAW in WAR (Reach All Women in War)

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

Right Livelihood Award Foundation

Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights

Sahrawi Media Observatory to document human rights violations

SALAM for Democracy and Human Rights (SALAM DHR)

Scholars at Risk (SAR)

Sham Center for Democratic Studies and Human Rights in Syria

Sisters’ Arab Forum for Human Rights (SAF) – Yemen

Solicitors International Human Rights Group

Syrian Center for Legal Studies and Research

Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM)

Tanmiea – Iraq

Tunisian Association to Defend Academic Values

Tunisian Association to Defend Individual Rights

Tunisian Association of Democratic Women

Tunis Center for Press Freedom

Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights

Tunisian League to Defend Human Rights

Tunisian Organization against Torture

Urgent Action Fund for Women’s Human Rights (UAF)

Urnammu

Vietnam Committee on Human Rights

Vigdis Freedom Foundation

Vigilance for Democracy and the Civic State

Women Human Rights Defenders International Coalition

Women’s Center for Culture & Art – United Kingdom

World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (WAN-IFRA)

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) within the framework of the Observatory for the protection of human rights defenders

Yemen Center for Human Rights

Zimbabwe Human Rights Association (ZimRights)

17Shubat For Human Rights

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”95198″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]For the second time since 2013, the United Nations (UN) Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) has issued an Opinion regarding the legality of the detention of Mr. Nabeel Rajab under international human rights law.

In its second opinion, the WGAD held that the detention was not only arbitrary but also discriminatory. The 127 signatory human rights groups welcome this landmark opinion, made public on 13 August 2018, recognising the role played by human rights defenders in society and the need to protect them. We call upon the Bahraini Government to immediately release Nabeel Rajab in accordance with this latest request.

In its Opinion (A/HRC/WGAD/2018/13), the WGAD considered that the detention of Mr. Nabeel Rajabcontravenes Articles 2, 3, 7, 9, 10, 11, 18 and 19 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights and Articles 2, 9, 10, 14, 18, 19 and 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, ratified by Bahrain in 2006. The WGAD requested the Government of Bahrain to “release Mr. Rajab immediately and accord him an enforceable right to compensation and other reparations, in accordance with international law.”

This constitutes a landmark opinion as it recognises that the detention of Mr. Nabeel Rajab – President of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR), Founding Director of the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR), Deputy Secretary General of FIDH and a member of the Human Rights Watch Middle East and North Africa Advisory Committee – is arbitrary and in violation of international law, as it results from his exercise of the right to freedom of opinion and expression as well as freedom of thought and conscience, and furthermore constitutes “discrimination based on political or other opinion, as well as on his status as a human rights defender.” Mr. Nabeel Rajab’s detention has therefore been found arbitrary under both categories II and V as defined by the WGAD.

Mr. Nabeel Rajab was arrested on 13 June 2016 and has been detained since then by the Bahraini authorities on several freedom of expression-related charges that inherently violate his basic human rights. On 15 January 2018, the Court of Cassation upheld his two-year prison sentence, convicting him of “spreading false news and rumors about the internal situation in the Kingdom, which undermines state prestige and status” – in reference to television interviews he gave in 2015 and 2016. Most recently on 5 June 2018, the Manama Appeals Court upheld his five years’ imprisonment sentence for “disseminating false rumors in time of war”; “offending a foreign country” – in this case Saudi Arabia; and for “insulting a statutory body”, in reference to comments made on Twitter in March 2015 regarding alleged torture in Jaw prison and criticising the killing of civilians in the Yemen conflict by the Saudi Arabia-led coalition. The Twitter case will next be heard by the Court of Cassation, the final opportunity for the authorities to acquit him.

The WGAD underlined that “the penalisation of a media outlet, publishers or journalists solely for being critical of the government or the political social system espoused by the government can never be considered to be a necessary restriction of freedom of expression,” and emphasised that “no such trial of Mr. Rajab should have taken place or take place in the future.” It added that the WGAD “cannot help but notice that Mr. Rajab’s political views and convictions are clearly at the centre of the present case and that the authorities have displayed an attitude towards him that can only be characterised as discriminatory.” The WGAD added that several cases concerning Bahrain had already been brought before it in the past five years, in which WGAD “has found the Government to be in violation of its human rights obligations.” WGAD added that “under certain circumstances, widespread or systematic imprisonment or other severe deprivation of liberty in violation of the rules of international law may constitute crimes against humanity.”

Indeed, the list of those detained for exercising their right to freedom of expression and opinion in Bahrain is long and includes several prominent human rights defenders, notably Mr. Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja, Dr.Abduljalil Al-Singace and Mr. Naji Fateel – whom the WGAD previously mentioned in communications to the Bahraini authorities.

Our organisations recall that this is the second time the WGAD has issued an Opinion regarding Mr. Nabeel Rajab. In its Opinion A/HRC/WGAD/2013/12adopted in December 2013, the WGAD already classified Mr. Nabeel Rajab’s detention as arbitrary as it resulted from his exercise of his universally recognised human rights and because his right to a fair trial had not been guaranteed (arbitrary detention under categories II and III as defined by the WGAD).The fact that over four years have passed since that opinion was issued, with no remedial action and while Bahrain has continued to open new prosecutions against him and others, punishing expression of critical views, demonstrates the government’s pattern of disdain for international human rights bodies.

To conclude, our organisations urge the Bahrain authorities to follow up on the WGAD’s request to conduct a country visit to Bahrain and to respect the WGAD’s opinion, by immediately and unconditionally releasing Mr. Nabeel Rajab, and dropping all charges against him. In addition, we urge the authorities to release all other human rights defenders arbitrarily detained in Bahrain and to guarantee in all circumstances their physical and psychological health.

This statement is endorsed by the following organisations:

1- ACAT Germany – Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture

2- ACAT Luxembourg

3- Access Now

4- Acción Ecológica (Ecuador)

5- Americans for Human Rights and Democracy in Bahrain – ADHRB

6- Amman Center for Human Rights Studies – ACHRS (Jordania)

7- Amnesty International

8- Anti-Discrimination Center « Memorial » (Russia)

9- Arabic Network for Human Rights Information – ANHRI (Egypt)

10- Arab Penal Reform Organisation (Egypt)

11- Armanshahr / OPEN Asia (Afghanistan)

12- ARTICLE 19

13- Asociación Pro Derechos Humanos – APRODEH (Peru)

14- Association for Defense of Human Rights – ADHR

15- Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression – AFTE (Egypt)

16- Association marocaine des droits humains – AMDH

17- Bahrain Center for Human Rights

18- Bahrain Forum for Human Rights

19- Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy – BIRD

20- Bahrain Interfaith

21- Cairo Institute for Human Rights – CIHRS

22- CARAM Asia (Malaysia)

23- Center for Civil Liberties (Ukraine)

24- Center for Constitutional Rights (USA)

25- Center for Prisoners’ Rights (Japan)

26- Centre libanais pour les droits humains – CLDH

27- Centro de Capacitación Social de Panama

28- Centro de Derechos y Desarrollo – CEDAL (Peru)

29- Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales – CELS (Argentina)

30- Centro de Políticas Públicas y Derechos Humanos – Perú EQUIDAD

31- Centro Nicaragüense de Derechos Humanos – CENIDH (Nicaragua)

32- Centro para la Acción Legal en Derechos Humanos – CALDH (Guatemala)

33- Citizen Watch (Russia)

34- CIVICUS : World Alliance for Citizen Participation

35- Civil Society Institute – CSI (Armenia)

36- Colectivo de Abogados « José Alvear Restrepo » (Colombia)

37- Collectif des familles de disparu(e)s en Algérie – CFDA

38- Comisión de Derechos Humanos de El Salvador – CDHES

39- Comisión Ecuménica de Derechos Humanos – CEDHU (Ecuador)

40- Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos (Costa Rica)

41- Comité de Acción Jurídica – CAJ (Argentina)

42- Comité Permanente por la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos – CPDH (Colombia)

43- Committee for the Respect of Liberties and Human Rights in Tunisia – CRLDHT

44- Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative – CHRI (India)

45- Corporación de Defensa y Promoción de los Derechos del Pueblo – CODEPU (Chile)

46- Dutch League for Human Rights – LvRM

47- European Center for Democracy and Human Rights – ECDHR (Bahrain)

48- FEMED – Fédération euro-méditerranéenne contre les disparitions forcées

49- FIDH, in the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

50- Finnish League for Human Rights

51- Foundation for Human Rights Initiative – FHRI (Uganda)

52- Front Line Defenders

53- Fundación Regional de Asesoría en Derechos Humanos – INREDH (Ecuador)

54- Groupe LOTUS (DRC)

55- Gulf Center for Human Rights

56- Human Rights Association – IHD (Turkey)

57- Human Rights Association for the Assistance of Prisoners (Egypt)

58- Human Rights Center – HRIDC (Georgia)

59- Human Rights Center « Memorial » (Russia)

60- Human Rights Center « Viasna » (Belarus)

61- Human Rights Commission of Pakistan

62- Human Rights Foundation of Turkey

63- Human Rights in China

64- Human Rights Mouvement « Bir Duino Kyrgyzstan »

65- Human Rights Sentinel (Ireland)

66- Human Rights Watch

67- I’lam – Arab Center for Media Freedom, Development and Research

68- IFEX

69- IFoX Turkey – Initiative for Freedom of Expression

70- Index on Censorship

71- International Human Rights Organisation « Club des coeurs ardents » (Uzbekistan)

72- International Legal Initiative – ILI (Kazakhstan)

73- Internet Law Reform Dialogue – iLaw (Thaïland)

74- Institut Alternatives et Initiatives Citoyennes pour la Gouvernance Démocratique – I-AICGD (RDC)

75- Instituto Latinoamericano para una Sociedad y Derecho Alternativos – ILSA (Colombia)

76- Internationale Liga für Menschenrechte (Allemagne)

77- International Service for Human Rights – ISHR

78- Iraqi Al-Amal Association

79- Jousor Yemen Foundation for Development and Humanitarian Response

80- Justice for Iran

81- Justiça Global (Brasil)

82- Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and the Rule of Law

83- Latvian Human Rights Committee

84- Lawyers’ Rights Watch Canada

85- League for the Defense of Human Rights in Iran

86- League for the Defense of Human Rights – LADO Romania

87- Legal Clinic « Adilet » (Kyrgyzstan)

88- Liga lidských práv (Czech Republic)

89- Ligue burundaise des droits de l’Homme – ITEKA (Burundi)

90- Ligue des droits de l’Homme (Belgique)

91- Ligue ivoirienne des droits de l’Homme

92- Ligue sénégalaise des droits humains – LSDH

93- Ligue tchadienne des droits de l’Homme – LTDH

94- Ligue tunisienne des droits de l’Homme – LTDH

95- MADA – Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedom

96- Maharat Foundation (Lebanon)

97- Maison des droits de l’Homme du Cameroun – MDHC

98- Maldivian Democracy Network

99- MARCH Lebanon

100- Media Association for Peace – MAP (Lebanon)

101- MENA Monitoring Group

102- Metro Center for Defending Journalists’ Rights (Iraqi Kurdistan)

103- Monitoring Committee on Attacks on Lawyers – International Association of People’s Lawyers

104- Movimento Nacional de Direitos Humanos – MNDH (Brasil)

105- Mwatana Organisation for Human Rights (Yemen)

106- Norwegian PEN

107- Odhikar (Bangladesh)

108- Pakistan Press Foundation

109- PEN America

110- PEN Canada

111- PEN International

112- Promo-LEX (Moldova)

113- Public Foundation – Human Rights Center « Kylym Shamy » (Kyrgyzstan)

114- RAFTO Foundation for Human Rights

115- Réseau Doustourna (Tunisia)

116- SALAM for Democracy and Human Rights

117- Scholars at Risk

118- Sisters’ Arab Forum for Human Rights – SAF (Yemen)

119- Suara Rakyat Malaysia – SUARAM

120- Taïwan Association for Human Rights – TAHR

121- Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights – FTDES

122- Vietnam Committee for Human Rights

123- Vigilance for Democracy and the Civic State

124- World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers – WAN-IFRA

125- World Organisation Against Torture – OMCT, in the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

126- Yemen Organisation for Defending Rights and Democratic Freedoms

127- Zambia Council for Social Development – ZCSD[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1535551119543-359a0849-e6f7-3″ taxonomies=”716″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The first editor of Index on Censorship magazine reflects on the driving forces behind its founding in 1972″ google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]A version of this article first appeared in Index on Censorship magazine in December 1981. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The first issue of Index on Censorship Magazine, 1972

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”My friends and I think it would be very important to create an international committee or council that would make it its purpose to support the democratic movement in the USSR.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Looking back, not only over the thirty years since Index was started, but much further, over the history of our civilisation, one cannot help but realise that censorship is by no means a recent phenomenon.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/09/free-to-air/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

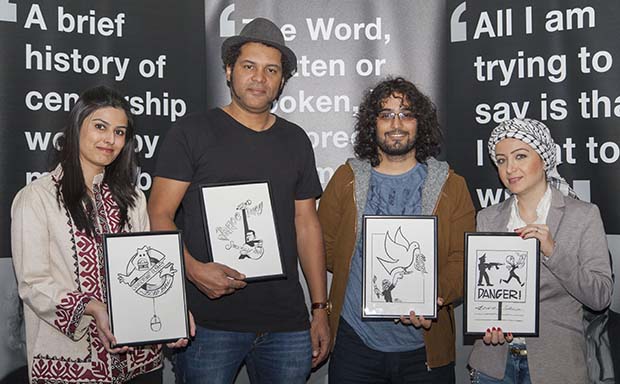

Winners of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards: from left, Farieha Aziz of Bolo Bhi (campaigning), Serge Bambara — aka “Smockey” (Music in Exile), Murad Subay (arts), Zaina Erhaim (journalism). GreatFire (digital activism), not pictured, is an anonymous collective. Photo: Sean Gallagher for Index on Censorship

In the short three months since the Index on Censorship Awards, the 2016 fellows have been busy doing important work in their respective fields to further their cause and for stronger freedom of expression around the world.

GreatFire / Digital activism

GreatFire, the anonymous group of individuals who work towards circumventing China’s Great Firewall, has just launched a groundbreaking new site to test virtual private networks within the country.

“Stable circumvention is a difficult thing to find in China so this new site a way for people to see what’s working and what’s not working,” said co-founder Charlie Smith.

But why are VPNs needed in China in the first place? “The list is very long: the firewall harms innovation while scholars in China have criticised the government for their internet controls, saying it’s harming their scholarly work, which is absolutely true,” said Smith. “Foreign companies are also complaining that internet censorship is hurting their day-to-day business, which means less investment in China, which means less jobs for Chinese people.”

Even recent Chinese history is skewed by the firewall. The anniversary of Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 last month went mostly unnoticed. “There was nothing to be seen about it on the internet in China,” Smith said. “This is a major event in Chinese history that’s basically been erased.”

Going forward, Smith is optimistic for growth within GreatFire, and has hopes the new VPN service will reach 100 million Chinese people. “However, we always feel that foreign businesses and governments could do more,” he said. “We don’t see this as a long game or diplomacy; we want change now and so I feel positive about what we are doing but we have less optimism when it comes to efforts outside of our organisation.”

Winning the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for Digital Activism has certainly helped morale. “With the way we operate in anonymity, sometimes we feel a little lonely, so it’s nice to know that there are people out there paying attention,” Smith said.

Murad Subay / Arts

During his time in London for the Index awards, Yemeni artist Murad Subay painted a mural in Hoxton, which was the first time he had worked outside of his home country. “It was a great opportunity to tell people what’s going on in Yemen, because the world isn’t paying attention,” he explained to Index.

Since going home, Subay has continued to work with Ruins, his campaign with other artists to paint the walls of Yemen. “We launched in 2011, and have continued to paint ever since.”

The Saw mural, Ruins campaign https://t.co/z7XrE2yTP7 pic.twitter.com/ZMiVjhxZO8

— murad subay (@muradsubay) June 10, 2016

Last month, artists from Ruins, including Subay, painted a number of murals in front of the Central Bank of Yemen to represent the country’s economic collapse.

Thi Yazen Alalawi mural, Ruins campaign https://t.co/c2wkosUIxy pic.twitter.com/UqmuSzczAl

— murad subay (@muradsubay) June 10, 2016

In his acceptance speech at the Index Awards, Subay dedicated his award to the “unknown” people of Yemen, “who struggle to survive”. There has been little change in the situation since in the subsequent months as Yemenis continue to suffer war, oppression, destruction, thirst and — with increasing food prices — hunger.

“The war will continue for a long time and I believe it may even be a decade for the turmoil in Yemen to subside,” Subay says. “Yemen has always been poor, but the situation has gotten significantly worse in the last few years.”

Subay considers himself to be one of the lucky ones as he has access to water and electricity. “But there are many millions of people without these things and they need humanitarian assistance,” he says. “They are sick of what is going on in Yemen, but I do have hope — you have to have hope here.”

The Index award has also helped Subay maintain this hope. As has the inclusion of his work in university courses around the world, from John Hopkins University in Baltimore, USA, and King Juan Carlos University in Madrid, Spain.

Subay’s wife has this month travelled to America to study at Stanford University. He hopes to join her and study fine art. “Since 2001 I have not had any education, and this is not enough,” he explains. “I have ideas in my head that I can’t put into practice because i don’t have the knowledge but a course would help with this.”

Zaina Erhaim / Journalism

Syrian journalist and documentary filmmaker Zaina Erhaim has been based in Turkey since leaving London after the Index Awards in April as travelling back to Syria isn’t currently possible. “We don’t have permission to cross back and forth from the Turkish authorities,” she told Index. “The border is completely closed.”

Erhaim is with her daughter in Turkey, while her husband Mahmoud remains in Aleppo.

“The situation in Aleppo is very bad,” she said. “A recent Channel 4 report by a friend of mine shows that the bombing has intensified, and the number of killings is in the tens per day, which hasn’t been the case for some weeks; it’s terrible.”

The main hospital in Aleppo was bombed twice in June. “Sadly this is becoming such a common thing that we don’t talk about it anymore,” Erhaim added.

She has largely given up on following coverage of the war in Syria through US or UK-based media outlets. “It is such a wasted effort and it’s so disappointing,” she explained. “I follow a couple of journalists based in the region who are actually trying to report human-side stories, but since I was in London for the awards, I haven’t followed the mainstream western media.”

Erhaim has put her own documentary making on hold for now while she launches a new project with the Institute for War and Peace Reporting this month to teach activists filmmaking skills. “We are going to be helping five citizen journalists to do their own short films, which we will then help them publicise,” she said.

Documentary filmmaking is something she would like to return to in future, “but at the moment it is not feasible with the situation in Syria and the projects we are now working on”.

Bolo Bhi / Campaigning

The last time Index spoke to Farieha Aziz, director of Bolo Bhi, the Pakistani non-profit, all-female NGO fighting for internet access, digital security and privacy, the country’s lower legislative chamber had just passed the cyber crimes bill.

The danger of the bill is that it would permit the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority to manage, remove or block content on the internet. “It’s part of a regressive trend we are seeing the world over: there is shrinking space for openness, a lot of privacy intrusion and limits to free speech,” Aziz told Index.

Thankfully, when the bill went to the Pakistani senate — which is the upper house — it was rejected as it stood. “Before this, we had approached senators to again get an affirmation as they’d given earlier saying that they were not going to pass it in its current form,” Aziz added.

Bolo Bhi’s advice to Pakistani politicians largely pointed back to analysis the group had published online, which went through various sections of the bill and highlighting what was problematic and what needed to be done.

This further encouraged those senators who were against the bill to get the word out to their parties to attend the session to ensure it didn’t pass. “It’s a good thing to see they’ve felt a sense of urgency, which we’ve desperately needed,” Aziz said.

“The strength of the campaign throughout has actually been that we’ve been able to band together, whether as civil society organisations, human rights organisations, industry organisations, but also those in the legislature,” Aziz added. “We’ve been together at different forums, we’ve been constantly engaging, sharing ideas and essentially that’s how we want policy making in general, not just on one bill, to take place.”

The campaign to defeat the bill goes on. A recent public petition (18 July) set up by Bolo Bhi to the senate’s Standing Committee on IT and Telecom requested the body to “hold more consultations until all sections of the bill have been thoroughly discussed and reviewed, and also hold a public hearing where technical and legal experts, as well as other concerned citizens, can present their point of view, so that the final version of the bill is one that is effective in curbing crime and also protects existing rights as guaranteed under the Constitution of Pakistan”.

A vote on an amended version of the bill is due to take place this week in the senate.

Smockey / Music in Exile Fellow

Burkinabe rapper and activist Smockey became the inaugural Music in Exile Fellow at the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards, and last month his campaigning group Le Balai Citoyen (The Citizen’s Broom) won an Amnesty International Ambassador of Conscience Award.

“This was was given to us for our efforts in the promotion of human rights and democracy in our country,” said Smockey. The award was also given to Y en a marre (Senegal) and Et Lucha (Democratic Republic of the Congo).

“We are trying to create a kind of synergy between all social-movements in Africa because we are living in the same continent and so anything that affects the others will affect us also,” Smockey added.

Le Balai Citoyen has recently been working on programmes for young people and women. “We will also meet the new mayor of the capital to understand all the problems of urbanism,” Smockey added.

While his activism has been getting international recognition, he remains focused on making music with upcoming concerts in Belgium, Switzerland and Germany, and he is currently writing the music for an upcoming album. A major setback has seen Smockey’s acclaimed Studio Abazon destroyed by a fire early in the morning of 19 July. According to press reports the studio is a complete loss. The cause is under investigation.

Despite this, Smockey is still planning to organise a new music festival in Burkina Faso. “We want to create a festival of free expression in arts,” Smockey said. “And we are confident that it will change a lot of things here.”

He is thankful for the exposure the Index Awards have given him over the last number of months. “It was a great honour to receive this award, especially because it came from an English country,” he said. “My people are proud of this award.”