18 Mar 2022 | 50 years of Index, China, History, Ireland, Magazine, News and features, Philippines, United Kingdom, United States, Volume 51.01 Spring 2022 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

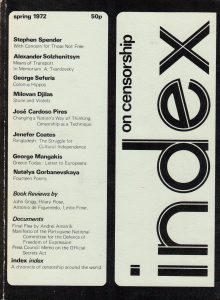

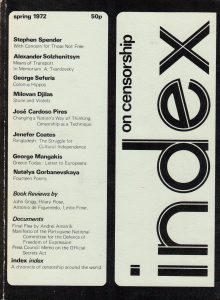

The first issue of Index on Censorship magazine, in March 1972.

You may have heard that the 70s were different. In 1972, when the first issue of Index magazine was launched, no one knew that 20 years later there would be an influential economic bloc called the European Union. The Beatles’ had only just split. The World Trade Center in New York was being built, while Sir Edward Heath was the prime minister of the United Kingdom.

Fifty years on and some things remain. Queen Elizabeth’s reign goes on and celebrates its 70th anniversary in 2022. Dictatorships and censorship, which should be trapped in history books, continue to torment the lives of many. And as a result, Index on Censorship remains vigilant, defending freedom of expression and giving voice to those who are silenced.

As we celebrate our 50th anniversary, we go back in time and remember the remarkable events that happened in 1972.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”1″][vc_column_text]January 30th: British soldiers shoot 26 unarmed civilians during a protest in Derry, Northern Ireland. Fourteen people were killed on this day known as “Bloody Sunday”. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”2″][vc_column_text]February 1st: Paul McCartney and the Wings release “Give Ireland back to the Irish” in the UK. It would be banned by the BBC, nine days later. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”3″][vc_column_text]February 5th: Airlines in the United States begin to inspect passengers and baggage. Tough to imagine that people traveled without any surveillance. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”4″][vc_column_text]February 17th: British Parliament votes to join the European Common Market. In 2020, the United Kingdom would leave the European Union. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”5″][vc_column_text]February 21st: Richard Nixon becomes the first US president to visit China, seeking to establish positive relations in a meeting with Chinese leader Mao Zedong, in Beijing.

Mao Zedong and Richard Nixon during Nixon’s historical visit to China in 1972. Photo: Ian Dagnall/Alamy

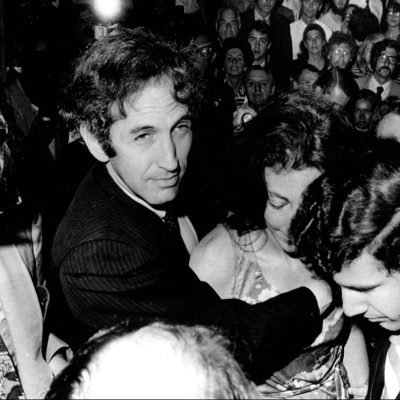

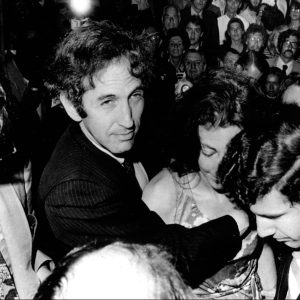

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”6″][vc_column_text]March 15th: The Godfather, starring Marlon Brando and Al Pacino, premieres in New York. It wins Best Picture and Best Actor (Brando) at the 45th Academy Awards.

Al Pacino and Marlon Brando in the Godfather. The first film of one the most successful franchises of all time was released in 1972. Photo: All Star Library/Alamy

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”7″][vc_column_text]June 18th: British European Airways Trident crashes after takeoff from Heathrow to Brussels, killing all 118 people on board. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”8″][vc_column_text]July 1st: Feminist magazine Ms, founded by Gloria Steinem, publishes its first issue, with Wonder Woman on the cover.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”9″][vc_column_text]August 4th: Uganda dictator Idi Amin orders the expulsion of 50,000 Asians with British passports.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”10″][vc_column_text]September 4th and 5th: 11 members of the Israeli Olympic team are murdered by a Palestinian terrorist group in the second week of the 1972 Olympics in Munich.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”11″][vc_column_text]September 21st: Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos declares martial law. In 2022, his son Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos is running for president. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”12″][vc_column_text]October 13th: A flight from Uruguay to Chile crashes in the Andes Mountains. Passengers eat the flesh of the deceased to survive. Sixteen people are rescued two months later.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”13″][vc_column_text]November 30th: BBC bans “Hi, Hi, Hi”, by Paul McCartney and The Wings, due to its drug references and suggestive sexual content. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”14″][vc_column_text]December 7th: Apollo 17 is launched and the crew takes the famous “blue marble” photo of the entire Earth.

The earth seen from the Apollo 17 spacecraft. Photo: NASA/Alamy

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”15″][vc_column_text]December 28th: Kim Il-Sung takes over as president of North Korea. He’s the grandfather of the country’s current leader, Kim Jong-un. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”16″][vc_column_text]December 30th: US President Richard Nixon halts bombing of North Vietnam and announces peace talks in Paris, to be held in January 1973. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

12 Apr 2021 | Ireland, Media Freedom, News and features, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom

As images of serious violence in Northern Ireland beamed around the world last week, many outside the post-conflict society wondered what had gone wrong.

The province, long hailed as one of the best examples of peacebuilding, was for the first time in recent years seeing petrol bombs, vehicle hijackings and masked figures back on the streets on an almost nightly basis.

There is no simple or straightforward explanation for the unrest, which started off in loyalist areas under the guise of peaceful protests.

Those demonstrations surrounded the 'Irish Sea border' or Northern Ireland Protocol, part of the Brexit deal that keeps NI aligned with EU rules and treated differently to the rest of the UK.

Controversy over the state prosecutor's move not to prosecute alleged coronavirus breaches by senior Sinn Fein members at the 2020 funeral of republican and former IRA man Bobby Storey, has also inflamed tensions. The belief in unionist and loyalist circles is that political favouritism played a part in that decision.

Add into the melting pot the recent disruption to loyalist paramilitary crime networks by the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), you now have a dangerous mix in a place where anger and frustration has long played out through street violence.

As rioting broke out and escalated across towns and cities, it didn't take long to spread to interface areas - adding a dangerous sectarian element to the violence.

On 7 April, three days before the 23rd anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, a bus travelling close to a peace divide in the capital of Belfast was hijacked and petrol bombed by loyalist youths.

It sparked scenes not seen on the streets of the loyalist Shankill Road and the Irish Republican stronghold of Lanark Way for some time.

As masonry, fireworks and Molotov cocktails were fired back and forth between hundreds of rival youths, a car rammed into the so-called peace gate that was locked to separate the two communities.

Ironically painted with the words, 'There Was Never A Good War Or A Bad Peace', the padlocked steel doors were eventually prised open allowing disorder and destruction to continue into the night, and years of priceless cross-community work put at risk.

News agencies around the world reported on the danger to Northern Ireland's fragile peace, and the fear that escalating sectarian violence could spiral it back to the dark days of the Troubles, when more than 3,000 people lost their lives.

Sporadic violence, unfortunately, has long been a part of Ulster's journey from war to peace; a peace that is not perfect but that has achieved the goal of convincing most people that a return to those days cannot, and will not, happen.

Rightfully, international political leaders took notice, expressing concern and calls for calm.

US President Joe Biden said he remained "steadfast" in his support "for a secure and prosperous Northern Ireland in which all communities have a voice and enjoy the gains of the hard-won peace".

What many do not realise is that the voices he refers to have been under threat for quite some time.

Over the last two years, dozens of journalists in Northern Ireland have been threatened by both loyalist and republican paramilitary groups for their work in exposing criminality and the grip these gangs still have on communities.

Those threats, mainly from loyalists, have escalated in recent times and are having a detrimental impact on press freedom in Northern Ireland.

In May 2020, reporters at both the Sunday World and Sunday Life newspapers received a blanket threat from South East Antrim Ulster Defence Association (UDA), a loyalist criminal cartel that was recently the subject of a high-profile drugs bust.

The gang threatened to take violent action against the journalists, with police informing each of them that intelligence suggests the gangsters may also intimidate their families.

The threats were condemned by major politicians, who in turn then each received death threats from the gang for speaking out in support of the media workers.

In November, the same criminals threatened a journalist with the Belfast Telegraph.

The same month, further loyalist death threats were delivered to the homes of two reporters working for the Sunday World newspaper.

They were informed by police that West Belfast UDA planned to carry out some form of attack on them.

Both had been covering intimidation and threats to those living in a loyalist area and had been named in threatening social media posts prior to being informed of the death threats.

Senior police told one journalist she would be shot, and that the PSNI had received information that the crime gang may try to entrap her.

Since the Northern Ireland Protocol was put in place on 1 January, threats have continued.

Two journalists had their names spray-painted on walls with gun cross hairs in February.

At least one of those was targeted by a paramilitary gang involved in talks with other loyalist groups over discontent over the Irish Sea Border.

Hours before the interface violence broke out in west Belfast last week, press photographer Kevin Scott was attacked as he covered the disorder for the Belfast Telegraph newspaper.

He was pulled to the ground by two masked men who smashed his cameras and threatened, before being told to: "fuck off back to your own area you fenian cunt".

At the same time 70 miles away, billboards were being erected in Derry by the family of murdered journalist Lyra McKee, appealing for information over her killing.

The 29-year-old was shot dead two years ago by a New IRA gunman as she observed a riot in the city's Creggan estate. No-one has been convicted over her murder.

As the anniversary of her murder approaches, threats to the safety of journalists have escalated to levels many have not seen in recent times, or even in their entire careers.

The distress and trauma of such threats is compounded by the fact those responsible are continually treated with impunity by the police.

Twenty years ago, Sunday World journalist Martin O'Hagan was assassinated by members of the violent Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF).

The killing gang - who have never been convicted - later released a statement saying the reporter had been murdered for "crimes against the loyalist people".

Two decades on the same type of language is not only bedecking lampposts across Northern Ireland in the form of anti-Irish Sea Border placards, but is also being used by those with influence in unionism and loyalism.

It is this type of hard rhetoric that has fed into the hostility to media workers here, who have been murdered and attacked as they go about their jobs.

Northern Ireland has paid a very high price for its peace; but what price must it pay to protect press freedom?