Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Timothy Garton Ash is no stranger to censorship. On the toilet wall of his Oxford home, there is a Polish censor’s verdict from early 1989 which cut a great chunk of text from an article of his on the bankruptcy of Soviet socialism.

Timothy Garton Ash is no stranger to censorship. On the toilet wall of his Oxford home, there is a Polish censor’s verdict from early 1989 which cut a great chunk of text from an article of his on the bankruptcy of Soviet socialism.

Six months later socialism was indeed bankrupt, although the formative experiences of travelling behind the Iron Curtain in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s — seeing friends such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn interrogated and locked up for what they published — never left him.

Now, in Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World, the professor of European Studies at Oxford University provides an argument for “why we need more and better free speech” and a blueprint for how we should go about it.

“The future of free speech is a decisive question for how we live together in a mixed up world where conventionally — because of mass migration and the internet — we are all becoming neighbours,” Garton Ash explains to Index on Censorship. “The book reflects a lot of the debates we’ve already been having on the Free Speech Debate website [the precursor to the book] as well as physically in places like India China, Egypt, Burma, Thailand, where I’ve personally gone to take forward these debates.”

Garton Ash began writing the book 10 years ago, shortly after the murder of Theo van Gough and the publication of the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons. In the second of the 10 principles of free speech — ranked in order of importance — he writes: “We neither make threats of violence nor accept violent intimidation.” What he calls the “assassin’s veto” — violence or the threat of violence as a response to expression — is, he tells Index, “one of the greatest threats to free speech in our time because it undoubtedly has a very wide chilling effect”.

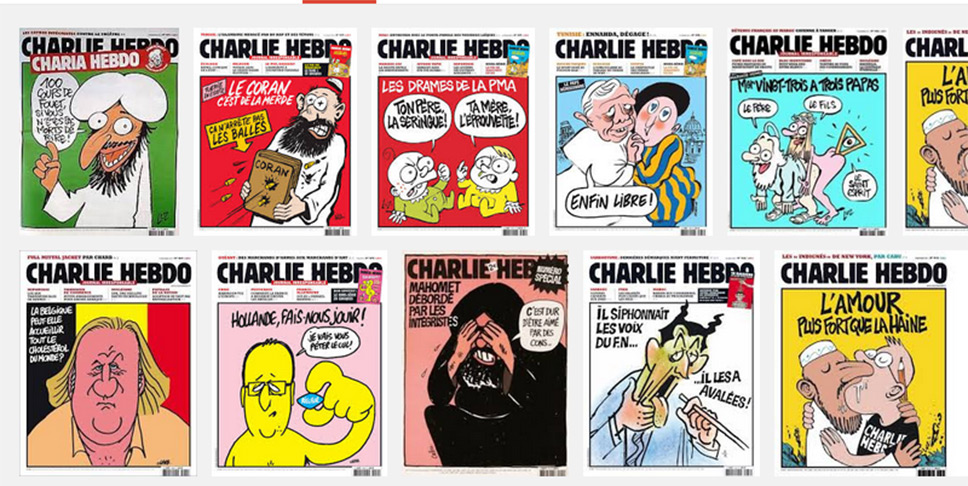

While the veto may bring to mind the January 2015 killings at Charlie Hebdo, Garton Ash is quick to point out that “while a lot of these threats do come from violent Islamists, they also come from the Italian mafia, Hindu nationalists in India and many other groups”.

Europe, in particular, has “had far too much yielding, or often pre-emptively, to the threat of violence and intimidation”, explains Garton Ash, including the 2014 shutting down of Exhibit B, an art exhibition which featured black performers in chains, after protesters deemed it racist. “My view is that this is extremely worrying and we really have to hold the line,” he adds.

Similarly, in the sixth principle from the book — “one of the most controversial” — Garton Ash states: “We respect the believer but not necessarily the content of the belief.”

This principle makes the same point the philosopher Stephen Darwall made between “recognition respect” and “appraisal respect”. “Recognition respect is ‘I unconditionally respect your full dignity, equal human dignity and rights as an individual, as a believer including your right to hold that belief’,” explains Garton Ash. “But that doesn’t necessarily mean I have to give ‘appraisal respect’ to the content of your belief, which I may find to be, with some reason, incoherent nonsense.”

The best and many times only weapon we have against “incoherent nonsense” is knowledge (principle three: We allow no taboos against and seize every chance for the spread of knowledge). In Garton Ash’s view, there are two worrying developments in the field of knowledge in which taboos result in free speech being edged away.

“On the one hand, the government, with its extremely problematic counter-terror legislation, is trying to impose a prevent duty to disallow even non-violent extremism,” he says. “Non-violent extremists, in my view, include Karl Marx and Jesus Christ; some of the greatest thinkers in the history of mankind were non-violent extremists.”

“On the other hand, you have student-led demands of no platforming, safe spaces, trigger warnings and so on,” Garton Ash adds, referring to the rising trend on campuses of shutting down speech deemed offensive. “Universities should be places of maximum free speech because one of the core arguments for free speech is it helps you to seek out the truth.”

The title of the books mentions the “connected world”, or what is also referred to in the text as “cosmopolis”, a global space that is both geographic and virtual. In the ninth principle, “We defend the internet and other systems of communication against illegitimate encroachments by both public and private powers”, Garton Ash aims to protect free expression in this online realm.

“We’ve never been in a world like this before, where if something dreadful happens in Iceland it ends up causing harm in Singapore, or vice-versa,” he says. “With regards to the internet, you have to distinguish online governance from regulation and keep the basic architecture of the internet free, and that means — where possible — net neutrality.”

A book authored by a westerner in an “increasingly post-western” world clearly has its work cut out for it to convince people in non-western or partially-western countries, Garton Ash admits. “What we can’t do and shouldn’t do is what the West tended to do in the 1990s, and say ‘hey world, we’ve worked it out — we have all the answers’ and simply get out the kit of liberal democracy and free speech like something from Ikea,” he says. “If you go in there just preaching and lecturing, immediately the barriers go up and out comes postcolonial resistance.”

“But what we can do — and I try to do in the book — is to move forward a conversation about how it should be, and having looked at their own traditions, you will find people are quite keen to have the conversation because they’re trying to work it out themselves.”

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A drawing by French cartoonist t0ad

Freedom of expression is a fundamental human right. It reinforces all other human rights, allowing society to develop and progress. The ability to express our opinion and speak freely is essential to bring about change in society.

Free speech is important for many other reasons. Index spoke to many different experts, professors and campaigners to find out why free speech is important to them.

Index on Censorship magazine editor, Rachael Jolley, believes that free speech is crucial for change. “Free speech has always been important throughout history because it has been used to fight for change. When we talk about rights today they wouldn’t have been achieved without free speech. Think about a time from the past – women not being allowed the vote, or terrible working conditions in the mines – free speech is important as it helped change these things” she said.

Free speech is not only about your ability to speak but the ability to listen to others and allow other views to be heard. Jolley added: “We need to hear other people’s views as well as offering them your opinion. We are going through a time where people don’t want to be on a panel with people they disagree with. But we should feel comfortable being in a room with people who disagree with us as otherwise nothing will change.”

Human rights activist Peter Tatchell states that going against people who have different views and challenging them is the best way to move forward. He told Index: “Free speech does not mean giving bigots a free pass. It includes the right and moral imperative to challenge, oppose and protest bigoted views. Bad ideas are most effectively defeated by good ideas – backed up by ethics, reason – rather than by bans and censorship.”

Tatchell, who is well-known for his work in the LGBT community, found himself at the centre of a free speech row in February when the National Union of Students’ LGBT representative Fran Cowling refused to attend an event at the Canterbury Christ Church University unless he was removed from the panel; over Tatchell signing an open letter in The Observer protesting against no-platforming in universities.

Tatchell, who following the incident took part in a demonstration urging the UK National Union of Students to reform its safe space and no-platforming policies, told Index why free speech is important to him.

“Freedom of speech is one of the most precious and important human rights. A free society depends on the free exchange of ideas. Nearly all ideas are capable of giving offence to someone. Many of the most important, profound ideas in human history, such as those of Galileo Galilei and Charles Darwin, caused great religious offence in their time.”

On the current trend of no-platforming at universities, Tatchell added: “Educational institutions must be a place for the exchange and criticism of all ideas – even of the best ideas – as well as those deemed unpalatable by some. It is worrying the way the National Union of Students and its affiliated Student Unions sometimes seek to use no-platform and safe space policies to silence dissenters, including feminists, apostates, LGBTI campaigners, liberal Muslims, anti-fascists and critics of Islamist extremism.”

Article continues below

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Stay up to date on free speech” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that defends people’s freedom to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution. We fight censorship around the world.

To find out more about Index on Censorship and our work protecting free expression, join our mailing list to receive our weekly newsletter, monthly events email and periodic updates about our projects and campaigns. See a sample of what you can expect here.

Index on Censorship will not share, sell or transfer your personal information with third parties. You may may unsubscribe at any time. To learn more about how we process your personal information, read our privacy policy.

You will receive an email asking you to confirm your subscription to the weekly newsletter, monthly events roundup and periodic updates about our projects and campaigns.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Professor Chris Frost, the former head of journalism at Liverpool John Moores University, told Index of the importance of allowing every individual view to be heard, and that those who fear taking on opposing ideas and seek to silence or no-platform should consider that it is their ideas that may be wrong. He said: “If someone’s views or policies are that appalling then they need to be challenged in public for fear they will, as a prejudice, capture support for lack of challenge. If we are unable to defeat our opponent’s arguments then perhaps it is us that is wrong.

“I would also be concerned at the fascism of a majority (or often a minority) preventing views from being spoken in public merely because they don’t like them and find them difficult to counter. Whether it is through violence or the abuse of power such as no-platform we should always fear those who seek to close down debate and impose their view, right or wrong. They are the tyrants. We need to hear many truths and live many experiences in order to gain the wisdom to make the right and justified decisions.”

Free speech has been the topic of many debates in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks. The terrorist attack on the satirical magazine’s Paris office, in January 2015, has led to many questioning whether free speech is used as an excuse to be offensive.

Many world leaders spoke out in support of Charlie Hebdo and the hashtag #Jesuischarlie was used worldwide as an act of solidarity. However, the hashtag also faced some criticism as those who denounced the attacks but also found the magazine’s use of a cartoon of the Prophet Mohammed offensive instead spoke out on Twitter with the hashtag #Jenesuispascharlie.

After the city was the victim of another terrorist attack at the hands of ISIS at the Bataclan Theatre in November 2015, President François Hollande released a statement in which he said: “Freedom will always be stronger than barbarity.” This statement showed solidarity across the country and gave a message that no amount of violence or attacks could take away a person’s freedom.

French cartoonist t0ad told Index about the importance of free speech in allowing him to do his job as a cartoonist, and the effect the attacks have had on free speech in France: “Mundanely and along the same tracks, it means I can draw and post (social media has changed a hell of a lot of notions there) a drawing without expecting the police or secret services knocking at my door and sending me to jail, or risking being lynched. Cartoonists in some other countries do not have that chance, as we are brutally reminded. Free speech makes cartooning a relatively risk-free activity; however…

“Well, you know the howevers: Charlie Hebdo attacks, country law while globalisation of images and ideas, rise of intolerances, complex realities and ever shorter time and thought, etc.

“As we all see, and it concerns the other attacks, the other countries. From where I stand (behind a screen, as many of us), speech seems to have gone freer … where it consists of hate – though this should not be defined as freedom.”

In the spring 2015 issue of Index on Censorship, following the Charlie Hebdo attacks, Richard Sambrook, professor of Journalism and director of the Centre for Journalism at Cardiff University, took the opportunity to highlight the number journalists that a murdered around the world every day for doing their job, yet go unnoticed.

Sambrook told Index why everyone should have the right to free speech: “Firstly, it’s a basic liberty. Intellectual restriction is as serious as physical incarceration. Freedom to think and to speak is a basic human right. Anyone seeking to restrict it only does so in the name of seeking further power over individuals against their will. So free speech is an indicator of other freedoms.

“Secondly, it is important for a healthy society. Free speech and the free exchange of ideas is essential to a healthy democracy and – as the UN and the World Bank have researched and indicated – it is crucial for social and economic development. So free speech is not just ‘nice to have’, it is essential to the well-being, prosperity and development of societies.”

Ian Morse, a member of the Index on Censorship youth advisory board told Index how he believes free speech is important for a society to have access to information and know what options are available to them.

He said: “One thing I am beginning to realise is immensely important for a society is for individuals to know what other ideas are out there. Turkey is a baffling case study that I have been looking at for a while, but still evades my understanding. The vast majority of educated and young populations (indeed some older generations as well) realise how detrimental the AKP government has been to the country, internationally and socially. Yet the party still won a large portion of the vote in recent elections.

“I think what’s critical in each of these elections is that right before, the government has blocked Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook – so they’ve simultaneously controlled which information is released and produced a damaging image of the news media. The media crackdown perpetuates the idea that the news and social media, except the ones controlled by the AKP, are bad for the country.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1538130760855-7d9ccb72-bf30-2″ taxonomies=”571, 986″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

When I started working at Index on Censorship, some friends (including some journalists) asked why an organisation defending free expression was needed in the 21st century. “We’ve won the battle,” was a phrase I heard often. “We have free speech.”

There was another group who recognised that there are many places in the world where speech is curbed (North Korea was mentioned a lot), but most refused to accept that any threat existed in modern, liberal democracies.

After the killing of 12 people at the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, that argument died away. The threats that Index sees every day – in Bangladesh, in Iran, in Mexico, the threats to poets, playwrights, singers, journalists and artists – had come to Paris. And so, by extension, to all of us.

Those to whom I had struggled to explain the creeping forms of censorship that are increasingly restraining our freedom to express ourselves – a freedom which for me forms the bedrock of all other liberties and which is essential for a tolerant, progressive society – found their voice. Suddenly, everyone was “Charlie”, declaring their support for a value whose worth they had, in the preceding months, seemingly barely understood, and certainly saw no reason to defend.

The heartfelt response to the brutal murders at Charlie Hebdo was strong and felt like it came from a united voice. If one good thing could come out of such killings, I thought, it would be that people would start to take more seriously what it means to believe that everyone should have the right to speak freely. Perhaps more attention would fall on those whose speech is being curbed on a daily basis elsewhere in the world: the murders of atheist bloggers in Bangladesh, the detention of journalists in Azerbaijan, the crackdown on media in Turkey. Perhaps this new-found interest in free expression – and its value – would also help to reignite debate in the UK, France and other democracies about the growing curbs on free speech: the banning of speakers on university campuses, the laws being drafted that are meant to stop terrorism but which can catch anyone with whom the government disagrees, the individuals jailed for making jokes.

And, in a way, this did happen. At least, free expression was “in vogue” for much of 2015. University debating societies wanted to discuss its limits, plays were written about censorship and the arts, funds raised to keep Charlie Hebdo going in defiance against those who would use the “assassin’s veto” to stop them. It was also a tense year. Events discussing hate speech or cartooning for which six months previously we might have struggled to get an audience were now being held to full houses. But they were also marked by the presence of police, security guards and patrol cars. I attended one seminar at which a participant was accompanied at all times by two bodyguards. Newspapers and magazines across London conducted security reviews.

But after the dust settled, after the initial rush of apparent solidarity, it became clear that very few people were actually for free speech in the way we understand it at Index. The “buts” crept quickly in – no one would condone violence to deal with troublesome speech, but many were ready to defend a raft of curbs on speech deemed to be offensive, or found they could only defend certain kinds of speech. The PEN American Center, which defends the freedom to write and read, discovered this in May when it awarded Charlie Hebdo a courage award and a number of novelists withdrew from the gala ceremony. Many said they felt uncomfortable giving an award to a publication that drew crude caricatures and mocked religion.

Index’s project Mapping Media Freedom recorded 745 violations against media freedom across Europe in 2015.

The problem with the reaction of the PEN novelists is that it sends the same message as that used by the violent fundamentalists: that only some kinds of speech are worth defending. But if free speech is to mean anything at all, then we must extend the same privileges to speech we dislike as to that of which we approve. We cannot qualify this freedom with caveats about the quality of the art, or the acceptability of the views. Because once you start down that route, all speech is fair game for censorship – including your own.

As Neil Gaiman, the writer who stepped in to host one of the tables at the ceremony after others pulled out, once said: “…if you don’t stand up for the stuff you don’t like, when they come for the stuff you do like, you’ve already lost.”

Index believes that speech and expression should be curbed only when it incites violence. Defending this position is not easy. It means you find yourself having to defend the speech rights of religious bigots, racists, misogynists and a whole panoply of people with unpalatable views. But if we don’t do that, why should the rights of those who speak out against such people be defended?

In 2016, if we are to defend free expression we need to do a few things. Firstly, we need to stop banning stuff. Sometimes when I look around at the barrage of calls for various people to be silenced (Donald Trump, Germaine Greer, Maryam Namazie) I feel like I’m in that scene from the film Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels where a bunch of gangsters keep firing at each other by accident and one finally shouts: “Could everyone stop getting shot?” Instead of demanding that people be prevented from speaking on campus, debate them, argue back, expose the holes in their rhetoric and the flaws in their logic.

Secondly, we need to give people the tools for that fight. If you believe as I do that the free flow of ideas and opinions – as opposed to banning things – is ultimately what builds a more tolerant society, then everyone needs to be able to express themselves. One of the arguments used often in the wake of Charlie Hebdo to potentially excuse, or at least explain, what the gunmen did is that the Muslim community in France lacks a voice in mainstream media. Into this vacuum, poisonous and misrepresentative ideas that perpetuate stereotypes and exacerbate hatreds can flourish. The person with the microphone, the pen or the printing press has power over those without.

It is important not to dismiss these arguments but it is vital that the response is not to censor the speaker, the writer or the publisher. Ideas are not challenged by hiding them away and minds not changed by silence. Efforts that encourage diversity in media coverage, representation and decision-making are a good place to start.

Finally, as the reaction to the killings in Paris in November showed, solidarity makes a difference: we need to stand up to the bullies together. When Index called for republication of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons shortly after the attacks, we wanted to show that publishers and free expression groups were united not by a political philosophy, but by an unwillingness to be cowed by bullies. Fear isolates the brave – and it makes the courageous targets for attack. We saw this clearly in the days after Charlie Hebdo when British newspapers and broadcasters shied away from publishing any of the cartoons featuring the Prophet Mohammed. We need to act together in speaking out against those who would use violence to silence us.

As we see this week, threats against freedom of expression in Europe come in all shapes and sizes. The Polish government’s plans to appoint the heads of public broadcasters has drawn complaints to the Council of Europe from journalism bodies, including Index, who argue that the changes would be “wholly unacceptable in a genuine democracy”.

In the UK, plans are afoot to curb speech in the name of protecting us from terror but which are likely to have far-reaching repercussions for all. Index, along with colleagues at English PEN, the National Secular Society and the Christian Institute will be working to ensure that doesn’t happen. This year, as every year, defending free speech will begin at home.

Dunja Mijatovic is the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media. (Photo: OSCE/Micky Kroell)

Each autumn, more than 1,000 government and civil society representatives from 57 countries of the OSCE get together in Warsaw for a two-week discussion on a wide variety of human rights issues. The purpose of the meeting is to scrutinize each country’s performance on human rights standards they signed up to in areas such as free expression, free media and the panoply of basic rights prevalent in modern, liberal societies. It is designed to be a thoughtful and lively event that gets to the heart of implementing states’ commitments on the issues.

This year the first topic was dedicated to freedom of expression and the keynote speaker, Danish human rights lawyer Jacob Mchangama, raised “the issue du jour”: “Does a genuine commitment to tolerance, equality and nondiscrimination really depend on restricting the very freedom that has made possible the articulation and spread of new and progressive ideas from religious toleration in 17th century Europe, the abolishment of slavery, the equality of the sexes, criticism of apartheid and the rights of LGBT people?”

The issue, of course, is whether we need the spate of new laws enacted worldwide designed to somehow strike a balance between the right of free expression and the desire to weed out intolerance and hate in society.

In the wake of the Charlie Hebdo massacre in January, the answer to Mchangama’s question may well form the superstructure of the rights to free speech in the years to come.

We don’t need new laws. Indeed, it is time we stop looking at unbridled speech as something that promotes intolerance. We should see it as an opportunity to protect the rights of minorities and marginalised people to speak when the powerful are making distressing noises.

My reasoning is based on the simple view that when it comes to media freedom, those who govern least, govern best.

Even the best-intentioned laws cannot prevent intolerant speech. And general notions such as “hate speech” preferably should be avoided because they can be arbitrarily interpreted.

It is a decidedly New Age thought, likely first made popular by the 19th century essayist Henry David Thoreau in his essay on Civil Disobedience.

But today it is commonly thought that laws criminalising hate speech are beneficial to marginalized groups that need state protection. In reality, it is the marginalized groups who need the freedom of speak without fear of prosecution to press their causes and affirm their rights in society.

As Mchangama said in his address: “The freedoms that (sometimes) allow bigots to bait minorities are also the very freedoms that allow Muslims and Jews to practice their faiths freely. By further eroding these freedoms, no one is more than a political majority away from being the target rather than the beneficiary of laws against hatred and offence.”

Indeed, a significant development post-Charlie Hebdo has been the distressing comments by some that openly suggested the magazine’s staff “had it coming to them” for publishing illustrations satirising the prophet Muhammad. Just think of it: the victims of an outrageous act of silencing speech actually became, in some people’s eyes, the guilty ones.

It is time for some civility in the chaotic world of free speech. As I wrote shortly after the attack: “Intolerant speech should be primarily fought with more speech.” I still believe that is the foundation of any attempts to regulate content.

Following that line, I suggested, among other things, that participating states (the member countries of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe):

· Refrain from banning any form of public discussion or critical speech, no matter what it refers to;

· Take all possible measures to fight all forms of pressure, harassment or violence aimed at preventing opinions and ideas from being expressed or disseminated; and

· Eliminate restrictions to freedom of expression on the exclusive grounds of hatred, intolerance or potential offensiveness. Legislation should only focus on speech with can be directly connected to violent actions, harassment or other forms of unacceptable behavior against communities or certain parts of society.

My full statement on this issue.