14 Feb 2018 | Awards, News, Press Releases

- Judges include Serpentine CEO Yana Peel; BBC journalist Razia Iqbal

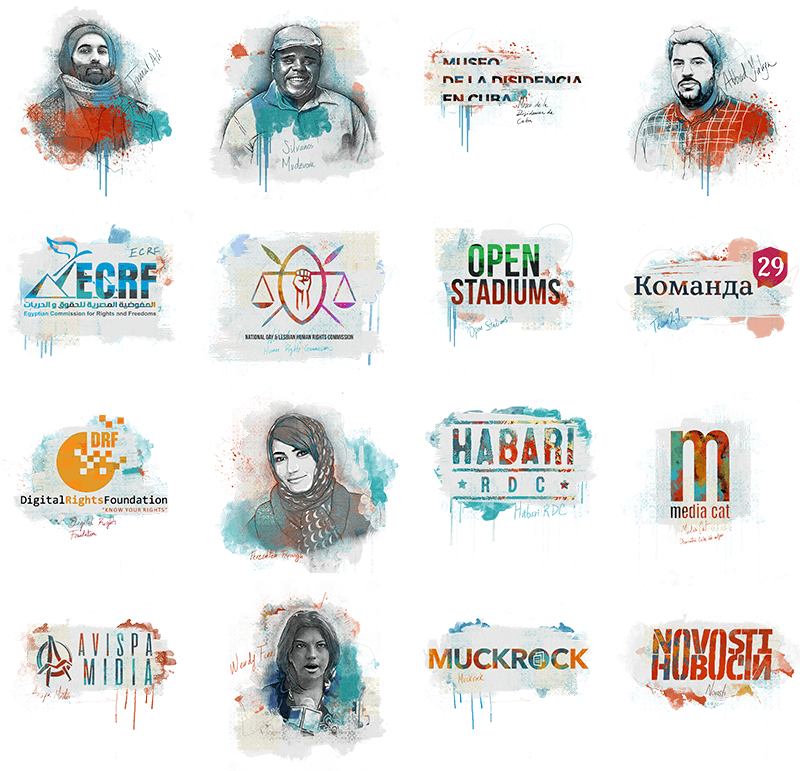

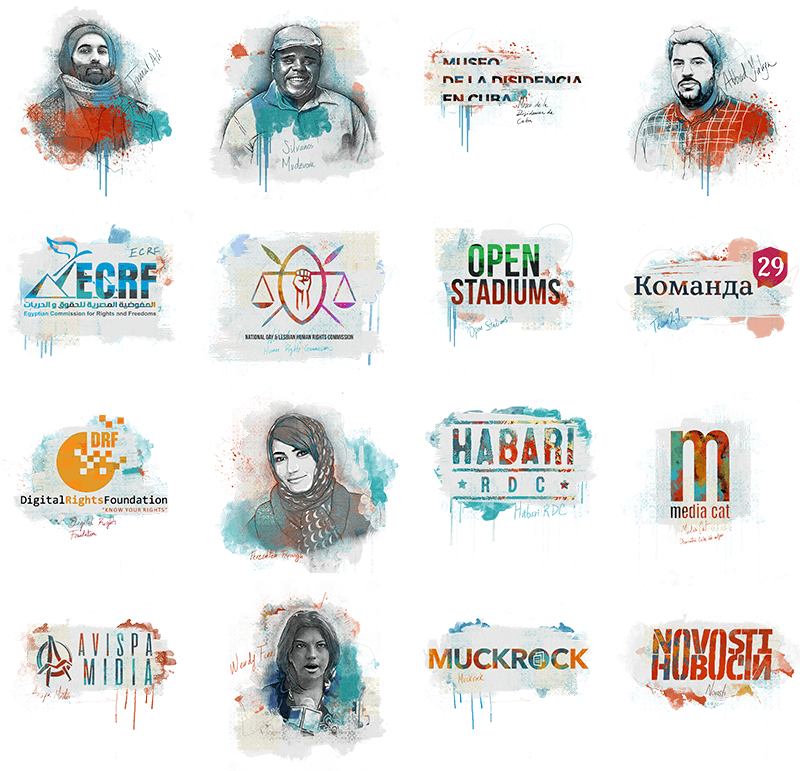

- Sixteen courageous individuals and organisations who fight for freedom of expression in every part of the world

An exiled Azerbaijani rapper who uses his music to challenge his country’s dynastic leadership, a collective of Russian lawyers who seek to uphold the rule of law, an Afghan seeking to economically empower women through computer coding and a Honduran journalist who goes undercover to expose her country’s endemic corruption are among the courageous individuals and organisations shortlisted for the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowships.

Drawn from more than 400 crowdsourced nominations, the shortlist celebrates artists, writers, journalists and campaigners overcoming censorship and fighting for freedom of expression against immense obstacles. Many of the 16 shortlisted nominees face regular death threats, others criminal prosecution or exile.

“Free speech is vital in creating a tolerant society. These nominees show us that even a small act can have a major impact. These groups and individuals have faced the harshest penalties for standing up for their beliefs. It’s an honour to recognise them,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of campaigning nonprofit Index on Censorship.

Awards fellowships are offered in four categories: arts, campaigning, digital activism and journalism.

Nominees include rapper Jamal Ali who challenged the authoritarian Azerbaijan government in his music – and whose family was targeted as a result; Team 29, an association of lawyers and journalists that defends those targeted by the state for exercising their right to freedom of speech in Russia; Fereshteh Forough, founder and executive director of Code to Inspire, a coding school for girls in Afghanistan; Wendy Funes, an investigative journalist from Honduras who regularly risks her life for her right to report on what is happening in the country.

Other nominees include The Museum of Dissidence, a public art project and website celebrating dissent in Cuba; the National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, a group proactively challenging LGBTI discrimination through the Kenya’s courts; Mèdia.cat, a Catalan website highlighting media freedom violations and investigating under-reported or censored stories; Novosti, a weekly Serbian-language magazine in Croatia that deals with a whole range of topics.

Judges for this year’s awards, now in its 18th year, are BBC reporter Razia Iqbal, CEO of the Serpentine Galleries Yana Peel, founder of Raspberry Pi CEO Eben Upton and Tim Moloney QC, deputy head of Doughty Street Chambers.

Iqbal says: “In my lifetime, there has never been a more critical time to fight for freedom of expression. Whether it is in countries where people are imprisoned or worse, killed, for saying things the state or others, don’t want to hear, it continues to be fought for and demanded. It is a privilege to be associated with the Index on Censorship judging panel.”

Winners, who will be announced at a gala ceremony in London on 19 April, become Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellows and are given year-long support for their work, including training in areas such as advocacy and communications.

“This award feels like a lifeline. Most of our challenges remain the same, but this recognition and the fellowship has renewed and strengthened our resolve to continue reporting, especially on the bleakest of days. Most importantly, we no longer feel so alone,” 2017 Freedom of Expression Awards Journalism Fellow Zaheena Rasheed said.

This year, the Freedom of Expression Awards are being supported by sponsors including SAGE Publishing, Google, Private Internet Access, Edwardian Hotels, Vodafone, media partner VICE News, Doughty Street Chambers and Psiphon. Illustrations of the nominees were created by Sebastián Bravo Guerrero.

Notes for editors:

- Index on Censorship is a UK-based non-profit organisation that publishes work by censored writers and artists and campaigns against censorship worldwide.

- More detail about each of the nominees is included below.

- The winners will be announced at a ceremony in London on 19 April.

For more information, or to arrange interviews with any of those shortlisted, please contact Sean Gallagher on 0207 963 7262 or [email protected].

More biographical information and illustrations of the nominees are available at indexoncensorship.org/indexawards2018.

Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship nominees 2018

ARTS

Jamal Ali

Azerbaijan

Jamal Ali is an exiled rapper and rock musician with a history of challenging Azerbaijan’s authoritarian regime. Ali was one of many who took to the streets in 2012 to protest spending around the country’s hosting of the Eurovision song contest. Detained and tortured for his role in the protests, he went into exile after his life was threatened. Ali has persisted in releasing music critical of the country’s dynastic leadership. Following the release of one song, Ali’s mother was arrested in a senseless display of aggression. In provoking such a harsh response with a single action, Ali has highlighted the repressive nature of the regime and its ruthless desire to silence all dissent.

Silvanos Mudzvova

Zimbabwe

Playwright and activist Silvanos Mudzvova uses performance to protest against the repressive regime of recently toppled President Robert Mugabe and to agitate for greater democracy and rights for his country’s LGBT community. Mudzvova specialises in performing so-called “hit-and-run” actions in public places to grab the attention of politicians and defy censorship laws, which forbid public performances without police clearance. His activism has seen him be traumatically abducted: taken at gunpoint from his home he was viciously tortured with electric shocks. Nonetheless, Mudzvova has resolved to finish what he’s started and has been vociferous about the recent political change in Zimbabwe.

The Museum of Dissidence

Cuba

The Museum of Dissidence is a public art project and website celebrating dissent in Cuba. Set up in 2016 by acclaimed artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and curator Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, their aim is to reclaim the word “dissident” and give it a positive meaning in Cuba. The museum organises radical public art projects and installations, concentrated in the poorer districts of Havana. Their fearlessness in opening dialogues and inhabiting public space has led to fierce repercussions: Nuñez was sacked from her job and Otero arrested and threatened with prison for being a “counter-revolutionary.” Despite this, they persist in challenging Cuba’s restrictions on expression.

Abbad Yahya

Palestine

Abbad Yahya is a Palestinian author whose fourth novel, Crime in Ramallah, was banned by the Palestinian Authority in 2017. The book tackles taboo issues such as homosexuality, fanaticism and religious extremism. It provoked a rapid official response and all copies of the book were seized. The public prosecutor issued a summons for questioning against Yahya while the distributor of the novel was arrested and interrogated. Yahya also received threats on social media and copies of the book were burned. Despite this, he has spent the last year giving interviews to international and Arab press and raising awareness of freedom of expression and the lives of young people in the West Bank and Gaza, particularly in relation to their sexuality.

CAMPAIGNING

Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms

Egypt

The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms or ECRF is one of the few human rights organisations still operating in a country which has waged an orchestrated campaign against independent civil society groups. Egypt is becoming increasingly hostile to dissent, but ECRF continues to provide advocacy, legal support and campaign coordination, drawing attention to the many ongoing human rights abuses under the autocratic rule of President Abdel Fattah-el-Sisi. Their work has seen them subject to state harassment, their headquarters have been raided and staff members arrested. ECRF are committed to carrying on with their work regardless of the challenges.

National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission

Kenya

The National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission is the only organisation in Kenya proactively challenging and preventing LGBTI discrimination through the country’s courts. Even though being homosexual isn’t illegal in Kenya, homosexual acts are. Homophobia is commonplace and men who have sex with men can be punished by up to 14 years in prison, and while no specific laws relate to women, former Prime Minister Raila Odinga has said lesbians should also be imprisoned. NGLHRC has had an impact by successfully lobbying MPs to scrap a proposed anti-homosexuality bill and winning agreement from the Kenya Medical Association to stop forced anal examination of clients “even in the guise of discovering crimes.”

Open Stadiums

Iran

The women behind Open Stadiums risk their lives to assert a woman’s right to attend public sporting events in Iran. The campaign that challenges the country’s political and religious regime, and engages women in an issue many human rights activists have previously thought unimportant. Iranian women face many restrictions on using public space. Open Stadiums has generated broad support for their cause in and out of the country. As a result, MPs and people in power are beginning to talk about women’s rights to attend sporting events in a way that would have been taboo before.

Team 29

Russia

Team 29 is an association of lawyers and journalists that defends those targeted by the state for exercising their right to freedom of speech in Russia. It is crucial work in a climate where hundreds of civil society organisations have been forced to close and where increasingly tight restrictions have been placed on public protest and political dissent since mass demonstrations rocked Russia in 2012. Team 29 conducts about 50 court cases annually, many involving accusations of high treason. Aside from litigation, they offer legal guides for activists, advice on what to do when state security comes for you and how to conduct yourself under interrogation.

DIGITAL ACTIVISM

Digital Rights Foundation

Pakistan

In late 2016, the Digital Rights Foundation established a cyber-harassment helpline that supported more than a thousand women in its first year of operation alone. Women make up only about a quarter of the online population in Pakistan but routinely face intense bullying including the use of revenge porn, blackmail, and other kinds of harassment. Often afraid to report how badly they are treated, women react by withdrawing from online spaces. To counter this, DRF’s Cyber Harassment Helpline team includes a qualified psychologist, digital security expert, and trained lawyer, all of whom provide specialised assistance.

Fereshteh Forough

Afghanistan

Fereshteh Forough is the founder and executive director of Code to Inspire, a coding school for girls in Afghanistan. Founded in 2015, this innovative project helps women and girls learn computer programming with the aim of tapping into commercial opportunities online and fostering economic independence in a country that remains a highly patriarchal and conservative society. Forough believes that with programming skills, an internet connection and using bitcoin for currency, Afghan women can not only create wealth but challenge gender roles and gain independence.

Habari RDC

Congo

Launched in 2016, Habari RDC is a collective of more than 100 young Congolese bloggers and web activists, who use Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to give voice to the opinions of young people from all over the Democratic Republic of Congo. Their site posts stories and cartoons about politics, but it also covers football, the arts and subjects such as domestic violence, child exploitation, the female orgasm and sexual harassment at work. Habari RDC offers a distinctive collection of funny, angry and modern Congolese voices, who are demanding to be heard.

Mèdia.cat

Spain

Mèdia.cat is a Catalan website devoted to highlighting media freedom violations and investigating under-reported or censored stories. Unique in Spain, it was a particularly significant player in 2017 when the heightened atmosphere in Catalonia over the disputed independence referendum brought issues of censorship and the impartiality of news under the spotlight. The website provides an online platform that catalogues systematically, publicly and in real time censorship perpetrated in the region. Its map on censorship offers a way for journalists to report on abuses they have personally suffered.

JOURNALISM

Avispa Midia

Mexico

Avispa Midia is an independent online magazine that prides itself on its daring use of multimedia techniques to bring alive the political, economic and social worlds of Mexico and Latin America. It specialises in investigations into organised criminal gangs and the paramilitaries behind mining mega-projects, hydroelectric dams and the wind and oil industry. Many of Avispa’s reports in the last 12 months have been focused on Mexico and Central America, where the media group has helped indigenous and marginalised communities report on their own stories by helping them learn to do audio and video editing. In the future, Avispa wants to create a multimedia journalism school to help indigenous and young people inform the world what is happening in their region, and break the stranglehold of the state and large corporations on the media.

Wendy Funes

Honduras

Wendy Funes is an investigative journalist from Honduras who regularly risks her life for her right to report on what is happening in the country, an extremely harsh environment for reporters. Two journalists were murdered in 2017 and her father and friends are among those who have met violent deaths in the country – killings for which no one has ever been brought to justice. Funes meets these challenges with creativity and determination. For one article she had her own death certificate issued to highlight corruption. Funes also writes about violence against women, a huge problem in Honduras where one woman is killed every 16 hours.

MuckRock

United States

MuckRock is a non-profit news site used by journalists, activists and members of the public to request and share US government documents in pursuit of more transparency. MuckRock has shed light on government surveillance, censorship and police militarisation among other issues. MuckRock produces its own reporting, and helps others learn more about requesting information. Last year the site produced a Freedom of Information Act 4 Kidz lesson plan to help educators to start discussions about government transparency. Since then, they have expanded their reach to Canada. The organisation hopes to continue increasing their impact by putting transparency tools in the hands of journalists, researchers and ordinary citizens.

Novosti

Croatia

Novosti is a weekly Serbian-language magazine in Croatia. Although fully funded as a Serb minority publication by the Serbian National Council, it deals with a whole range of topics, not only those directly related to the minority status of Croatian Serbs. In the past year, the outlet’s journalists have faced attacks and death threats mainly from the ultra-conservative far-right. For its reporting, the staff of Novosti have been met with protest under the windows of the magazine’s offices shouting fascist slogans and anti-Serbian insults, and told they would end up killed like Charlie Hebdo journalists. Despite the pressure, the weekly persists in writing the truth and defending freedom of expression.

25 Jan 2018 | News, Volume 46.04 Winter 2017

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” full_height=”yes” css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1516891729158{background: #ffffff url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/6MD4OKVXIG5JX3NEIA2M_prvw_63818-1024x683ss-1.jpg?id=97759) !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”After Gothenburg and Frankfurt book fairs faced tension over who was allowed to attend, we asked four leading thinkers, Peter Englund, Ola Larsmo, Jean-Paul Marthoz, Tobias Voss, to debate the issue” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:left|color:%23000000″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

WORDS APART

In the first of a series of pieces on where the line is drawn on freedom of speech at book fairs, DOMINIC HINDE interviews PETER ENGLUND, a former member of the Swedish Academy’s Nobel committee

Peter Englund is a familiar face around the world, even if many outside Sweden would struggle to place him straight away. For seven years, the award-winning author and former permanent secretary to the Swedish Academy was a fixture on TV screens, emerging each autumn to announce the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature.The Nobel committee has attracted criticism for some of its choices over the years, but Englund, who retired from the post in 2015, said its decisions were never politically charged, and that the Swedish tradition of open dialogue had always been a core principle.

“When I was permanent secretary I used to say that you could never win the Nobel Prize because of your political view, but that it was quite possible to win in spite of your political attitude. The Swedish Academy is also extremely conscious of the extraordinary importance of freedom of expression, not least because it is a basic requirement if writers and researchers are going to be able to work properly.”

Englund is a long-time supporter of free speech causes around the world and, in his own work, has written extensively about totalitarianism in Europe under both communist and fascist regimes. He recently joined the debate closer to home on the competing demands of freedom of speech and growing right-wing movements in Sweden.

The past decade has seen the emergence of far-right populism in the traditionally liberal and open Nordic state. The Sweden Democrats party – who grew from the fringe white power movement in the 1990s – have made significant inroads in parliament and an alternative far-right media has blossomed. More extreme neo-Nazi groups have ridden on the coat tails of the Sweden Democrats and asserted their right to protest in the name of free speech, claiming Sweden is a country in decline, where the mainstream media ignores crime and immigration issues. Englund and some of his fellow writers have increasingly found themselves dubbed an elite of “cultural Marxists” by far- right activists. There is even a Swedish word – åsiktskorridor – which specifically refers to the narrow corridor of opinion extremists assert is allowed by the political establishment.

“I think it is important that we quite simply refuse to recognise this description of the situation. It is an important part of the populist right’s tactics to whip up ‘culture wars’ over more-or-less fictional symbolic questions, and you have to avoid letting yourself get dragged in,” said Englund.

Confronted with the openly anti-democratic and xenophobic politics which is emerging, many on the Swedish left and centre-right have begun to grapple with how Sweden, which has the oldest press freedom laws in the world, can reconcile its commitment to free speech and diversity with such views. In September 2017, the debate came to a head when Nya Tider (New Times), a populist right-wing newspaper, which has been accused of publishing fake news, was booked to appear at the annual Gothenburg Book Fair.

The fair is Sweden’s biggest cultural and journalistic event, but several well-known journalists and writers who would usually be there chose to stay away in protest at Nya Tider’s attendance. Some argued that Sweden’s tradition of a free press meant even the far-right were entitled to have their opinions heard, but Englund and others decided not to take part.

“I chose not to participate because it meant that I would have to appear on the same stage – broadly speaking – as these right-wing extremists, homophobes, conspiracy theorists, anti-Semites, Holocaust deniers and Putin supporters, and that would have helped to normalise their views,” argued Englund.

He believes that freedom of expression does not mean automatically welcoming extremists to all platforms, and that the Swedish commitment to an open society does not entail encouraging participation by extremist voices.

“Another important tactic for the populist right is to make themselves mainstream, and that is not something I want to contribute to” he explained. “For me [The Gothenburg controversy] was not a question of freedom of expression. That freedom remains intact. Nobody has tried to stop their paper being printed or attacked their journalists. On top of that, freedom of expression does not mean that you can be allowed to say anything at all, and does not mean that you have an absolute right to take part in any kind of forum.”

Events in Gothenburg reflected a wider disagreement in Swedish society about how best to counter populist politics and where the line between freedom of expression and extremism sits. Englund acknowledges that opponents of the far-right have not always got this right. The country goes to the polls in less than a year and the Sweden Democrats have ambitions to play a role in government, meaning the question may soon become more pressing than ever.

“In Sweden there have been attempts to deal with the far-right question through a combination of shutting them out and through triangulation,” he said. “Shutting them out means refusing to co-operate with them. Triangulation is not about accepting their description of the situation, or their proposed methods for dealing with it, but about understanding that among their voters there is a frustration, and even a fear, which does somehow need to be addressed, and which you can neither ignore nor tweet to death with smart sarcastic posts.

“History is fairly instructive on this. A necessary step for those sorts of movements to come to power – and this happened in both Italy and Germany – was that already established power structures had to invite them in, operating under the serious misconception that they could then be tamed. Those countries that were able to avoid fascism in the 1930s did it not least by showing resistance instead.”

That means being prepared to challenge those from all sides who threaten democratic principles, he believes.“We should, of course, be wary of the threat from the extreme right – the past tells us that – in the same way we have to keep an eye out for what is happening on the extreme left. I believe in democracy in Europe, but to avoid it meeting the same fate as the Weimar Republic, it has to be belligerent.”

Dominic Hinde is a journalist

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Swedish Academy is also extremely conscious of the extraordinary importance of freedom of expression” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

WHY I ATTENDED GOTHENBURG

Award-winning Swedish author OLA LARSMO explains why he went to the Gothenburg Book Fair

One of the important freedom of expression debates in Sweden has been running for about a year now and concerns the annual Gothenburg Book Fair. When it was announced that the extreme right-wing publication Nya Tider was allowed to rent a space at the 2017 Fair, some 200 Swedish writers wrote in a joint statement that they would not attend. This sparked a heated debate. What about defending the rights of people to spread deplorable or even dangerous opinions? What happens if you don’t?

I decided to attend the fair – along with other writers who stated that they would not be run out of the place by extremists. But I have great respect for those who chose not to. We are all trying to defend society against what must be considered a rising tide of fascism. But how to do that, and at the same time defend freedom of speech?

On 7 April 2017, a man hijacked a truck in central Stockholm and drove down a pedestrian street, targeting everyone in his way. Five people were killed. The suspect later said he was acting as a supporter of Isis. The response from ordinary people was massive. Beside the mountain of flowers in central Stockholm, it was obvious that everybody was determined to counteract the intimidation of terror by going on with life as normally as they could, because the trust between ordinary citizens is what makes an open society possible.

This was very much at the back of my mind when I decided to go to the fair. We also managed to organise a number of seminars and events that addressed the threat hate speech poses to freedom of speech. It felt like an opportunity to point to the elephant in the middle of the room.

Nya Tider is not “banned” – in fact they receive a tax- financed grant of about $358,167 – the same as other papers with the same circulation. The question was whether the fair had an obligation to open its space to a paper associated with the extreme right. Since the fair is a private enterprise, many felt that they were within their rights to choose their exhibitors freely.

During the last few years, Swedish writers, journalists and politicians have been facing a rising wave of death threats and hate speech. Solid research shows that these threats emanate mostly from right-wing extremists and, to a lesser degree, from radical Islamists.

They target publicists with the purpose of driving them to self-censorship.

So how, then, should society deal with these threats with- out lowering the ceiling for freedom of speech? That this threat is real became obvious as a demonstration of several hundred neo-Nazis tried to reach the fair on the Saturday, but were stopped by the Gothenburg police. The attendance that day shrank to half the ordinary numbers.Writers are a specific target for these extremists, and the 200 writers stated openly that they did not want to share the floor with a paper associated with that political agenda.Personally I feel that those of us committed to defending freedom of speech have to use all powers to counter the double threat we are now facing: that of intimidation through hate speech and, on the other hand, stronger legislation that threatens to smother what it is supposed to defend. We can’t close our eyes to either.

Ola Larsmo is a long-time president of Swedish PEN

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

MAKING IT FAIR

No serious book fair could exclude or censor a legal publication, argues Frankfurt’s vice president of international affairs TOBIAS VOSS

The Frankfurt Book Fair is a commercial enterprise. Yet the “commodity” we trade in is a very distinctive one: books convey ideas and, among other things, ideas significantly shapes social discourse, whether aesthetic, moral or political in nature. In this respect, it is necessary to regularly question the limiting of “critical” or “problematic” content. All book fairs thrive on the diversity of content presented by participants. In this regard, book fairs that strive to meet this objective are, therefore, a demonstration of the diversity of opinion and discourse. No serious international book fair that aims to represent the market and diversity of opinion is in a position to exclude or censor market players.

This approach – tolerating at times extremely problematic positions – must then also apply to titles that are perceived as an affront, as offensive or downright repugnant, by segments of the public.

The only exception for such a ban or exclusion is existing legislation. Only if a title is forbidden by law in Germany, then we feel it is right to ban this title or even the actual fair participant, from the exhibition.

Our book fair respects the separation of powers as an essential organisational principle for guaranteeing democratic freedoms, the associated institutions and the decisions and measures established under it. Whenever existing laws are violated at Frankfurt, we, as the organiser, will take action against this infringement through the department of public prosecution and the police.

A functioning democracy must tolerate dissent (as it has, after all, done successfully in Germany for decades), and must accept that the freedom of expression also applies to segments of the public that question – and at times even wish to do away with – the established legal order. The fair does not see it as its duty to establish its own political, moral or aesthetic criteria for permitting or forbidding things.

In keeping with its principles, the Frankfurt is committed to freedom of expression, freedom of publication, dialogue as a means of fair communication and respect for the democratic separation of powers and the decisions and measures that have been established to ensure it. The fair demonstrates this position in a wide variety of ways – through international involvement, by supporting the “Cities of Refuge” project and by curating well over 200 discussion events at our event and at book fairs abroad.

Tobias Voss is vice president, international affairs, of the Frankfurt Book Fair

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Crowds gather outside the Frankfurt Book Fair, the world’s largest book trade-fair, Marc Jacquemin/Frankfurt Book Fair

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

TALK THE TALK

Banning organisations with which you disagree means you don’t have the chance to argue your case, says JEAN-PAUL MARTHOZ

The recent Gothenburg and Frankfurt book fairs have again been riven with controversies around the presence of far-right publishers. From a progressive perspective, banning the far-right seems the appropriate thing to do. The rationale is clear: the barbarians are at the gates and no one has ever said that democracies should offer their foes the rope with which to hang them.

From a liberal point of view, however, things are not so easy. Liberal democracies are, by definition, committed to providing space to ideas that radically question their most essential values – and even threaten their very existence.

There should be freedom for the enemies of freedom. As long as far-right publishers are not legally banned, and don’t exhibit books that clearly flout the law, there are few arguments against them which would pass Voltaire’s test on freedom of expression.

While the far-right has been associated with the most thuggish forms of censorship, its leaders have been effective in denouncing the progressives’ “fear of the truth”. Free speech for me, but not for thee?

By principle, liberals should not concede one of their most iconic values to the far- right, even if the latter has opportunistically hijacked free speech in order to provide a veneer of respectability to hate speech.

Banning can be seen as a confession of weakness or an admission that liberal arguments are not convincing enough to be – nor capable of being – expressed in a way which might distract potential far-right sympathisers from extremist organisations.

In fact, any attempt to get the far-right out of the public arena only reinforces one of its core recruiting arguments: “patriots” are victims of a conspiracy in a “rigged system” run by a cosmopolitan and hypocritical liberal establishment.

Responding to the far-right is all the more crucial today, since it has the capacity to get around its exclusion and reach a wide audience through the internet and social networks. The only way to reduce its influence is to produce counter-arguments and alter- native discourse and disseminate them widely beyond the converted.

Banning an organisation, or censoring its ideas, too often exempts it from the rigorous and imaginative thinking which is the only effective way to push back and win the battle of ideas.

Jean-Paul Marthoz is a Belgian journalist and essayist. He is the author of The Media and Terrorism (2017, Unesco)

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”93959″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533808″][vc_custom_heading text=”Book fair detention” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533808|||”][vc_column_text]December 1984

An excerpt from Mindblast, a book by Dambudzo Marechera, which was due to be launched at the Second Zimbabwe Book Fair.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94784″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227508532452″][vc_custom_heading text=”Sweden: Limits of press freedom” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064227508532452|||”][vc_column_text]September 1975

Blaine Stothard reports on the Swedish Watergate and potential limits on press freedom.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”90797″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229808536482″][vc_custom_heading text=”White noise: separatist rock” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229808536482|||”][vc_column_text]November 1998

Neo-Nazi groups are recruiting throughout the developed world; leading the drive are their high energy, punk-derived anthems of hate. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”What price protest?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In homage to the 50th anniversary of 1968, the year the world took to the streets, the winter 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at all aspects related to protest.

With: Micah White, Ariel Dorfman, Robert McCrum[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Dec 2017 | About Index, History, Magazine, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The first editor of Index on Censorship magazine reflects on the driving forces behind its founding in 1972″ google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]A version of this article first appeared in Index on Censorship magazine in December 1981. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The first issue of Index on Censorship Magazine, 1972

Starting a magazine is as haphazard and uncertain a business as starting a book-who knows what combination of external events and subjective ideas has triggered the mind to move in a particular direction? And who knows, when starting, whether the thing will work or not and what relation the finished object will bear to one’s initial concept? That, at least, was my experience with Index, which seemed almost to invent itself at the time and was certainly not ‘planned’ in any rational way. Yet looking back, it is easy enough to trace the various influences that brought it into existence.

It all began in January 1968 when Pavel Litvinov, grandson of the former Soviet Foreign Minister, Maxim Litvinov, and his Englis wife, Ivy, and Larisa Bogoraz, the former wife of the writer, Yuli Daniel, addressed an appeal to world public opinion to condemn the rigged trial of two young writers and their typists on charges of ‘anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda’ (one of the writers, Alexander Ginzburg, was released from the camps in 1979 and now lives in Paris: the other, Yuri Galanskov, died in a camp in 1972). The appeal was published in The Times on 13 January 1968 and evoked an answering telegram of support and sympathy from sixteen English and American luminaries, including W H Auden, A J Ayer, Maurice Bowra, Julian Huxley, Mary McCarthy, Bertrand Russell and Igor Stravinsky.

The telegram had been organised and dispatched by Stephen Spender and was answered, after taking eight months to reach its addressees, by a further letter from Litvinov, who said in part: ‘You write that you are ready to help us “by any method open to you”. We immediately accepted this not as a purely rhetorical phrase, but as a genuine wish to help….’ And went on to indicate the kind oh help he had in mind:

My friends and I think it would be very important to create an international committee or council that would make it its purpose to support the democratic movement in the USSR. This committee could be composed of universally respected progressive writers, scholars, artists and public personalities from England, the United States, France, Germany and other western countries, and also from Latin America, Asia, Africa and, in the future, even from Eastern Europe…. Of course, this committee should not have an anti-communist or anti-Soviet character. It would even be good if it contained people persecuted in their own countries for pro-communist or independent views…. The point is not that this or that ideology is not correct, but that it must not use force to demonstrate its correctness.

Stephen Spender took up this idea first with Stuart Hampshire (the Oxford philosopher), a co-signatory of the telegram, and with David Astor (then editor of the Observer), who joined them in setting up a committee along the lines suggested by Litvinov (among its other members were Louis Blom-Cooper, Edward Crankshaw, Lord Gardiner, Elizabeth Longford and Sir Roland Penrose, and its patrons included Dame Peggy Ashcroft, Sir Peter Medawar, Henry Moore, Iris Murdoch, Sir Michael Tippett and Angus Wilson). It was not, admittedly, as international as Litvinov had suggested, but it was thought more practical to begin locally, so to speak, and to see whether or not there was something in it before expanding further. Nevertheless, the chosen name for the new organisation, Writers and Scholars International, was an earnest of its intentions, while its deliberate echo of Amnesty International (then relatively modest in size) indicated a feeling that not only literature but also human rights would be at issue.

By now it was 1971 and in the spring of that year the committee advertised for a director, held a series of interviews and offered me the job. There was no programme, other than Litvinov’s letter, there were no premises or staff, and there was very little money, but there were high hopes and enthusiasm.

It was at this point that some of the subjective factors I mentioned earlier began to come into play. Litvinov’s letter had indicated two possible forms of action. One was the launching of protests to ‘support and defend’ people who were being persecuted for their civic and literary activities in the USSR. The other was to ‘provide information to world public opinion’ about this state of affairs and to operate with ‘some sort of publishing house’. The temptation was to go for the first, particularly since Amnesty was setting such a powerful example, but precisely because Amnesty (and the International PEN Club) were doing such a good job already, I felt that the second option would be the more original and interesting to try. Furthermore, I knew that two of our most active members, Stephen Spender and Stuart Hampshire, on the rebound from Encounter after disclosures of CIA funding, had attempted unsuccessfully to start a new magazine, and I felt that they would support something in the publishing line. And finally, my own interests lay mainly in that direction. My experience had been in teaching, writing, translating and broadcasting. Psychologically I was too much of a shrinking violet to enjoy kicking up a fuss in public. I preferred argument and debate to categorical statements and protest, the printed page to the soapbox; I needed to know much more about censorship and human rights before having strong views of my own.

At that stage I was thinking in terms of trying to start some sort of alternative or ‘underground’ (as the term was misleadingly used) newspaper – Oz and the International Times were setting the pace were setting the pace in those days, with Time Out just in its infancy. But a series of happy accidents began to put other sorts of material into my hands. I had been working recently on Solzhenitzin and suddenly acquired a tape-recording with some unpublished poems in prose on it. On a visit to Yugoslavia, I called on Milovan Djilas and was unexpectedly offered some of his short stories. A Portuguese writer living in London, Jose Cardoso Pires, had just written a first-rate essay on censorship that fell into my hands. My friend, Daniel Weissbort, editor of Modern Poetry in Translation, was working on some fine lyrical poems by the Soviet poet, Natalya Gorbanevskaya, then in a mental hospital. And above all I stumbled across the magnificent ‘Letter to Europeans’ by the Greek law professor, George Mangakis, written in one of the colonels’ jails (which I still consider to be one of the best things I have ever published). It was clear that these things wouldn’t fit very easily into an Oz or International Times, yet it was even clearer that they reflected my true tastes and were the kind of writing, for better or worse, that aroused my enthusiasm. At the same time I discovered that from the point of view of production and editorial expenses, it would be far easier to produce a magazine appearing at infrequent intervals, albeit a fat one, than to produce even the same amount of material in weekly or fortnightly instalments in the form of a newspaper. And I also discovered, as Anthony Howard put it in an article about the New Statesman, that whereas opinions come cheap, facts come dear, and facts were essential in an explosive field like human rights. Somewhat thankfully, therefore, my one assistant and I settled for a quarterly magazine.

There is no point, I think, in detailing our sometimes farcical discussions of a possible title. We settled on Index (my suggestion) for what seemed like several good reasons: it was short; it recalled the Catholic Index Librorum Prohibitorum; it was to be an index of violations of intellectual freedom; and lastly, so help me an index finger pointing accusingly at the guilty oppressors – we even introduced a graphic of a pointing finger into our early issues. Alas, when we printed our first covers bearing the bold name of Index (vertically to attract attention nobody got the point (pun unintended). Panicking, we hastily added the ‘on censorship’ as a subtitle – Censorship had been the title of an earlier magazine, by then defunct – and this it has remained ever since, nagging me with its ungrammatically (index of censorship, surely) and a standing apology for the opacity of its title. I have since come to the conclusion that it is a thoroughly bad title – Americans, in particular, invariably associate it with the cost of living and librarians with, well indexes. But it is too late to change now.

Our first issue duly appeared in May 1972, with a programmatic article by Stephen Spender (printed also in the TLS) and some cautious ‘Notes’ by myself. Stephen summarised some of the events leading up to the foundation of the magazine (not naming Litvinov, who was then in exile in Siberia) and took freedom and tyranny as his theme:

Obviously there is a risk of a magazine of this kind becoming a bulletin of frustration. However, the material by writers which is censored in Eastern Europe, Greece, South Africa and other countries is among the most exciting that is being written today. Moreover, the question of censorship has become a matter of impassioned debate; and it is one which does not only concern totalitarian societies.

I contented myself with explaining why there would be no formal programme and emphasised that we would be feeling our way step by step. ‘We are naturally of the opinion that a definite need {for us} exists….But only time can tell whether the need is temporary or permanent—and whether or not we shall be capable of satisfying it. Meanwhile our aims and intentions are best judged…by our contents, rather than by editorials.’

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”My friends and I think it would be very important to create an international committee or council that would make it its purpose to support the democratic movement in the USSR.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

In the course of the next few years it became clear that the need for such a magazine was, if anything, greater than I had foreseen. The censorship, banning and exile of writers and journalists (not to speak of imprisonment, torture and murder) had become commonplace, and it seemed at times that if we hadn’t started Index, someone else would have, or at least something like it. And once the demand for censored literature and information about censorship was made explicit, the supply turned out to be copious and inexhaustible.

One result of being inundated with so much material was that I quickly learned the geography of censorship. Of course, in the years since Index began, there have been many changes. Greece, Spain, and Portugal are no longer the dictatorships they were then. There have been major upheavals in Poland, Turkey, Iran, the Lebanon, Pakistan, Nigeria, Ghana and Zimbabwe. Vietnam, Cambodia and Afghanistan have been silenced, whereas Chinese writers have begun to find their voices again. In Latin America, Brazil has attained a measure of freedom, but the southern cone countries of Chile, Argentina, Uruguay and Bolivia have improved only marginally and Central America has been plunged into bloodshed and violence.

Despite the changes, however, it became possible to discern enduring patterns. The Soviet empire, for instance, continued to maltreat its writers throughout the period of my editorship. Not only was the censorship there highly organised and rigidly enforced, but writers were arrested, tried and sent to jail or labour camps with monotonous regularity. At the same time, many of the better ones, starting with Solzhenitsyn, were forced or pushed into exile, so that the roll-call of Russian writers outside the Soviet Union (Solzhenitsyn, Sinyavksy, Brodsky, Zinoviev, Maximov, Voinovich, Aksyonov, to name but a few) now more than rivals, in talent and achievement, those left at home. Moreover, a whole array of literary magazines, newspapers and publishing houses has come into existence abroad to serve them and their readers.

In another main black spot, Latin America, the censorship tended to be somewhat looser and ill-defined, though backed by a campaign of physical violence and terror that had no parallel anywhere else. Perhaps the worst were Argentina and Uruguay, where dozens of writers were arrested and ill-treated or simply disappeared without trace. Chile, despite its notoriety, had a marginally better record with writers, as did Brazil, though the latter had been very bad during the early years of Index.

In other parts of the world, the picture naturally varies. In Africa, dissident writers are often helped by being part of an Anglophone or Francophone culture. Thus Wole Soyinka was able to leave Nigeria for England, Kofi Awoonor to go from Ghana to the United States (though both were temporarily jailed on their return), and French-speaking Camara Laye to move from Guinea to neighbouring Senegal. But the situation can be more complicated when African writers turn to the vernacular. Ngugi wa Thiong’o, who has written some impressive novels in English, was jailed in Kenya only after he had written and produced a play in his native Gikuyu.

In Asia the options also tend to be restricted. A mainland Chinese writer might take refuge in Hong Kong or Taiwan, but where is a Taiwanese to go? In Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, the possibilities for exile are strictly limited, though many have gone to the former colonising country, France, which they still regard as a spiritual home, and others to the USA. Similarly, Indonesian writers still tend to turn to Holland, Malaysians to Britain, and Filipinos to the USA.

In documenting these changes and movements, Index was able to play its small part. It was one of the very first magazines to denounce the Shah’s Iran, publishing as early as 1974 an article by Sadeq Qotbzadeh, later to become Foreign Minister in Ayatollah Khomeini’s first administration. In 1976 we publicised the case of the tortured Iranian poet, Reza Baraheni, whose testimony subsequently appeared on the op-ed page of the New York Times. (Reza Baraheni was arrested, together with many other writers, by the Khomeini regime on 19 October 1981.) One year later, Index became the publisher of the unofficial and banned Polish journal, Zapis, mouthpiece of the writers and intellectuals who paved the way for the present liberalisation in Poland. And not long after that it started putting out the Czech unofficial journal, Spektrum, with a similar intellectual programme. We also published the distinguished Nicaraguan poet, Ernesto Cardenal, before he became Minister of Education in the revolutionary government, and the South Korean poet, Kim Chi-ha, before he became an international cause célèbre.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Looking back, not only over the thirty years since Index was started, but much further, over the history of our civilisation, one cannot help but realise that censorship is by no means a recent phenomenon.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

One of the bonuses of doing this type of work has been the contact, and in some cases friendship, established with outstanding writers who have been in trouble: Solzhenitsyn, Djilas, Havel, Baranczak, Soyinka, Galeano, Onetti, and with the many distinguished writers from other parts of the world who have gone out of their way to help: Heinrich Böll, Mario Vargas Llosa, Stephen Spender, Tom Stoppard, Philip Roth—and many other too numerous to mention. There is a kind of global consciousness coming into existence, which Index has helped to foster and which is especially noticeable among writers. Fewer and fewer are prepared to stand aside and remain silent while their fellows are persecuted. If they have taught us nothing else, the Holocaust and the Gulag have rubbed in the fact that silence can also be a crime.

The chief beneficiaries of this new awareness have not been just the celebrated victims mentioned above. There is, after all, an aristocracy of talent that somehow succeeds in jumping all the barriers. More difficult to help, because unassisted by fame, are writers perhaps of the second or third rank, or young writers still on their way up. It is precisely here that Index has been at its best.

Such writers are customarily picked on, since governments dislike the opprobrium that attends the persecution of famous names, yet even this is growing more difficult for them. As the Lithuanian theatre director, Jonas Jurasas, once wrote to me after the publication of his open letter in Index, such publicity ‘deprives the oppressors of free thought of the opportunity of settling accounts with dissenters in secret’ and ‘bears witness to the solidarity of artists throughout the world’.

Looking back, not only over the years since Index was started, but much further, over the history of our civilisation, one cannot help but realise that censorship is by no means a recent phenomenon. On the contrary, literature and censorship have been inseparable pretty well since earliest times. Plato was the first prominent thinker to make out a respectable case for it, recommending that undesirable poets be turned away from the city gates, and we may suppose that the minstrels and minnesingers of yore stood to be driven from the castle if their songs displeased their masters. The examples of Ovid and Dante remind us that another old way of dealing with bad news was exile: if you didn’t wish to stop the poet’s mouth or cover your ears, the simplest solution was to place the source out of hearing. Later came the Inquisition, after which imprisonment, torture and execution became almost an occupational hazard for writers, and it is only in comparatively recent times—since the eighteenth century—that scribblers have fought back and demanded an unconditional right to say what they please. Needless to say, their demands have rarely and in few places been met, but their rebellion has resulted in a new psychological relationship between rulers and ruled.

Index, of course, ranged itself from the very first on the side of the scribblers, seeking at all times to defend their rights and their interests. And I would like to think that its struggles and campaigns have borne some fruit. But this is something that can never be proved or disproved, and perhaps it is as well, for complacency and self-congratulation are the last things required of a journal on human rights. The time when the gates of Plato’s city will be open to all is still a long way off. There are certainly many struggles and defeats still to come—as well, I hope, as occasional victories. When I look at the fragility of Index‘s a financial situation and the tiny resources at its disposal I feel surprised that it has managed to hold out for so long. No one quite expected it when it started. But when I look at the strength and ambitiousness of the forces ranged against it, I am more than ever convinced that we were right to begin Index in the first place, and that the need for it is as strong as ever. The next ten years, I feel, will prove even more eventful than the ten that have gone before.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Michael Scammell was the editor of Index on Censorship from 1972 to August 1980.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/09/free-to-air/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

9 Nov 2017 | Awards, Awards year slider

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1500380806420{padding-top: 250px !important;padding-bottom: 250px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/logo-2018-1460×490.jpg?id=94317) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row” css=”.vc_custom_1500449679881{margin-top: -50px !important;}”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”2018 FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AWARDS” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_row_inner disable_element=”yes”][vc_column_inner][vc_empty_space height=”15px”][vc_custom_heading text=”ABOUT THE AWARDS” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” content_placement=”middle”][vc_column_inner el_class=”awards-inside-desc” width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards exist to celebrate individuals or groups who have had a significant impact fighting censorship anywhere in the world.

- Awards are offered in four categories: Arts, Campaigning, Digital Activism and Journalism

- Anyone who has had a demonstrable impact in tackling censorship is eligible

- Winners are honoured at a gala celebration in London

- Winners join Index’s Awards Fellowship programme and receive dedicated training and support

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/a9Yl-nkwpig”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”2018 Fellowship” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Selected from over 400 public nominations and a shortlist of 16, the 2018 Freedom of Expression Awards Fellows exemplify courage in the face of censorship. Learn more about the fellowship.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”97994″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Arts | The Museum of Dissidence

The Museum of Dissidence is a public art project and website celebrating dissent in Cuba. Set up in 2016 by acclaimed artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and curator Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, their aim is to reclaim the word “dissident” and give it a positive meaning in Cuba. The museum organises radical public art projects and installations, concentrated in the poorer districts of Havana. Their fearlessness in opening dialogues and inhabiting public space has led to fierce repercussions: Nuñez was sacked from her job and Otero arrested and threatened with prison for being a “counter-revolutionary.” Despite this, they persist in challenging Cuba’s restrictions on expression.

Full profile | Speech[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”97988″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Campaigning | Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms

The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms is one of the few human rights organisations still operating in a country which has waged an orchestrated campaign against independent civil society groups. Egypt is becoming increasingly hostile to dissent, but ECRF continues to provide advocacy, legal support and campaign coordination, drawing attention to the many ongoing human rights abuses under the autocratic rule of President Abdel Fattah-el-Sisi. Their work has seen them subject to state harassment, their headquarters have been raided and staff members arrested. ECRF are committed to carrying on with their work regardless of the challenges.

Full profile | Speech[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”97990″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Digital Activism | Habari RDC

Launched in 2016, Habari RDC is a collective of more than 100 young Congolese bloggers and web activists, who use Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to give voice to the opinions of young people from all over the Democratic Republic of Congo. Their site posts stories and cartoons about politics, but it also covers football, the arts and subjects such as domestic violence, child exploitation, the female orgasm and sexual harassment at work. Habari RDC offers a distinctive collection of funny, angry and modern Congolese voices, who are demanding to be heard.

Full profile | Speech[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”98000″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Journalism | Wendy Funes

Wendy Funes is an investigative journalist from Honduras who regularly risks her life for her right to report on what is happening in the country, an extremely harsh environment for reporters. Two journalists were murdered in 2017 and her father and friends are among those who have met violent deaths in the country – killings for which no one has ever been brought to justice. Funes meets these challenges with creativity and determination. For one article she had her own death certificate issued to highlight corruption. Funes also writes about violence against women, a huge problem in Honduras where one woman is killed every 16 hours.

Full profile | Speech[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][awards_gallery_slider name=”2018 AWARDS GALA” images_url=”99875,99880,99879,99881,99882,99884,99885,99886,99887,99888,99889,99890,99891,99892,99893,99902,99906,99907,99908,99909,99910,99911,99912,99913,99914,99915,99916,99917,99918,99919,99920,99921,99922,99923,99924,99926,99925″][vc_column_text]

The Awards were held at London’s May Fair Hotel on Thursday 19 April 2018.

High-resolution images are available for download via Flickr.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”THE 2018 FELLOWSHIP SHORTLIST” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_tta_tabs][vc_tta_section title=”Arts” tab_id=”Arts”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

ARTS

for artists and arts producers whose work challenges repression and injustice and celebrates artistic free expression

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VfntVe_SrPY”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”97991″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/03/indexawards-2018-jamal-alis-music-fights-oppression-in-azerbaijan/”][vc_column_text]Jamal Ali, Azerbaijan[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”97998″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/03/index-awards-silvanos-mudzvova/”][vc_column_text]Silvanos Mudzvova, Zimbabwe[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”99853″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/03/indexawards2017-museum-of-dissidence-cuba-activism/”][vc_column_text]The Museum of Dissidence, Cuba[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”97985″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/03/index-awards-abbad-yahya/”][vc_column_text]Abbad Yahya, Palestine[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_tta_section][vc_tta_section title=”Campaigning” tab_id=”1524476396272-7b8a9fcb-bce7″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

CAMPAIGNING

for activists and campaigners who have had a marked impact in fighting censorship and promoting freedom of expression

Supported by Doughty Street Chambers

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iV2qFGmPhUU”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”99421″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/03/indexawards2018-ecrf-advocates-for-democratic-egypt/”][vc_column_text]Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms, Egypt[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”97995″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/03/index-awards-nglhrc/”][vc_column_text]National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, Kenya[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”97997″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/03/index-awards-open-stadiums/”][vc_column_text]Open Stadiums, Iran[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”97999″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/03/index-awards-team-29/”][vc_column_text]Team 29, Russia[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_tta_section][vc_tta_section title=”Digital activism” tab_id=”1524476516614-1a2ebb46-7ed2″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

DIGITAL ACTIVISM

for innovative uses of technology to circumvent censorship and enable free and independent exchange of information

Supported by Private Internet Access

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dz0rqQOlutw”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”97987″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/index-awards-digital-rights-foundation/”][vc_column_text]Digital Rights Foundation, Pakistan[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”97989″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/index-awards-fereshteh-forough/”][vc_column_text]Fereshteh Forough, Afghanistan[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”99851″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/index-awards-habari-rdc-digital-activism/”][vc_column_text]Habari RDC, Congo[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”97992″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/index-awards-media-cat-free-speech/”][vc_column_text]Mèdia.cat, Spain[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_tta_section][vc_tta_section title=”Journalism” tab_id=”1524476563543-4fdf3da9-962c”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

JOURNALISM

for courageous, high-impact and determined journalism that exposes censorship and threats to free expression

Sponsored by Vice News

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i8KfzAtARGQ”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”97986″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/index-awards-avispa-midia/”][vc_column_text]Avispa Midia, Mexico[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”99850″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/index-awards-wendy-funes/”][vc_column_text]Wendy Funes, Honduras[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”97993″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/index-awards-muck-rock/”][vc_column_text]MuckRock, United States[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”97996″ onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/novosti-combats-croatian-natinalism/”][vc_column_text]Novosti, Croatia[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_tta_section][/vc_tta_tabs][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row” css=”.vc_custom_1484569093244{background-color: #f2f2f2 !important;}”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”JUDGING” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_row_inner el_class=”mw700″][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Each year Index recruits an independent panel of judges – leading voices with diverse expertise across campaigning, journalism, the arts and human rights. Judges look for courage, creativity and resilience. We shortlist on the basis of those who are deemed to be making the greatest impact in tackling censorship in their chosen area, with a particular focus on topics that are little covered or tackled by others. Where a judge comes from a nominee’s country, or where there is any other potential conflict of interest, the judge will abstain from voting in that category.

The 2018 judging panel:

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Razia Iqbal” title=”Journalist” profile_image=”97201″]Razia Iqbal is a presenter for BBC News, where she is one of the main presenters of Newshour, the flagship news and current affairs programme on BBC World Service radio. [/staff][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Tim Moloney QC” title=”Barrister” profile_image=”97202″]Tim Moloney QC is the deputy head of Doughty Street Chambers. His practice encompasses crime, extradition, international criminal law, international death penalty litigation, public law and media law. [/staff][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Yana Peel” title=”Chief Executive” profile_image=”97203″]Yana Peel is CEO of the Serpentine Galleries, London, one of the most recognised organisations in the global contemporary art, design and architecture worlds. [/staff][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Eben Upton CBE” title=”Tech entrepreneur” profile_image=”97204″]Eben Upton CBE is a founder of the Raspberry Pi Foundation and serves as the CEO of Raspberry Pi (Trading), its commercial and engineering subsidiary.[/staff][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row” css=”.vc_custom_1510244917017{margin-top: 30px !important;}”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”THE FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AWARDS FELLOWSHIP” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F07%2F2018-freedom-of-expression-awards-fellowship%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

The Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship is open to any individual or organisation involved in tackling free expression threats – either through journalism, campaigning, the arts or using digital techniques – is eligible for nomination. Any individual, group or NGO can nominate or self-nominate. There is no cost to apply. Nominees must have had a recognisable impact in the past 12 months.

We offer Fellowships in four categories:[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” disable_element=”yes” el_class=”awards-4grid” css=”.vc_custom_1524481168193{margin-top: 20px !important;margin-bottom: 20px !important;}”][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1500449830213{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Arts” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]for artists and arts producers whose work challenges repression and injustice and celebrates artistic free expression[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1500449924825{background-color: #d98c00 !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Campaigning” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]for activists and campaigners who have had a marked impact in fighting censorship and promoting freedom of expression[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1500449960164{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Digital Activism” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]for innovative uses of technology to circumvent censorship and enable free and independent exchange of information[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1500449938665{background-color: #d98c00 !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Journalism” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]for courageous, high-impact and determined journalism that exposes censorship and threats to free expression[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1500380887889{margin-top: 20px !important;margin-bottom: 20px !important;background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Awards.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

By donating to the Freedom of Expression Awards you help us support individuals and groups at the forefront of tackling censorship.

Find out more

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1524481080226{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/2018-Fellows-4-web.jpg?id=99811) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: contain !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row disable_element=”yes”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”GALA” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][awards_gallery_slider name=”2017 Freedom of Expression Awards” images_url=”89583,89582,89581,89580,89579,89577,89578,89576,89575,89574,89565,89560,89559,89553,89552,89551,89550,89549,89548,89547,89546,89545,89544,89543,89542,89541,89540,89539,89538,89537,89536,89535,89534,89533,89532,89531,89530,89529,89528,89527,89526,89525,89524,89523,89522,89520,89521,89519,89518,89517,89516,89515,89514,89513,89512,89511,89510,89509″][vc_column_text]

The Awards were held at London’s Unicorn Theatre on Wednesday 19 April 2017.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” disable_element=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1500384168164{margin-top: 20px !important;margin-bottom: 20px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 15px !important;background-color: #f2f2f2 !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner content_placement=”middle” el_class=”container container980″][vc_column_inner][awards_news_slider name=”NEWS” years=”2017″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” css=”.vc_custom_1500453384143{margin-top: 20px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”SPONSORS” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1484567001197{margin-bottom: 30px !important;}”][vc_column_text]

The Freedom of Expression Awards and Fellowship have massive impact. You can help by sponsoring or supporting a fellowship.

Index is grateful to those who are supporting the 2018 Awards:

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” el_class=”container container980″][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”80918″ img_size=”234×234″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” img_link_target=”_blank” link=”https://uk.sagepub.com/”][vc_single_image image=”85983″ img_size=”234×234″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.privateinternetaccess.com/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”80921″ img_size=”234×234″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” img_link_target=”_blank” link=”https://www.google.co.uk/about/”][vc_single_image image=”85977″ img_size=”150×150″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://www.edwardian.com/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” el_class=”container container980″][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”82003″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” img_link_target=”_blank” link=”http://www.vodafone.com/content/index.html#”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”82323″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://news.vice.com/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”80923″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” img_link_target=”_blank” link=”http://www.doughtystreet.co.uk/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” el_class=”container container980″][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”80924″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” img_link_target=”_blank” link=”https://psiphon.ca/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

If you are interested in sponsorship you can contact [email protected]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]